June 1992

Your eyes or theirs?

Does the modern generation of birdwatcher have the confidence and the perception to continue the remarkable advances seen in bird identification over the past two decades? Veteran commentator Ian Wallace has his doubts.

On Sunday 12 April [1992], I completed the final first draft’ of the Field Characters for Volume 8 of Birds of the Western Palearctic and the last additions to the latest revision of the perennial Peterson Field Guide. There will be a year more of amendments and quite possibly corrections, but it does look as if my heaviest ever load in identification literature is at last off my back.

I should feel relief, but oddly, I don’t. There is something about a dropped mill-stone that one misses immediately. Already, I feel restless.

Also, I feel particularly uncertain over the value of the Field Character sections in BWP. Some have been openly derided in review – by no less a guru than passerine expert Lars Svensson – and others have been found wanting in action, as noted recently by Simon Harrap when trying to elucidate a white-headed, coffee-coloured falcon.

Writing the perfect field character text may well be impossible. Concerned that the early ones in Volume 1 of BWP were rather abstract, the senior editors asked me effectively to put the living bird back inside its separate characters. In an emphatically august tome, jizz and behaviour were to have their places.

As 17 years of periodic hard slog passed, I was first encouraged by at least murmured approval, particularly when Tim Sharrock spoke out against the modern involvement with too much minutiae in 1984; but eventually direct comments on the field character sections dried up completely. I sometimes found myself muttering “For God’s sake, say something, even if it’s only “Goodbye”.

Rather than whinge, however, I thought that it might be more instructive for you if I reviewed the identification literature at the start and end of the years of BWP preparation. Also, it might help if I noted what new field characters there are left for you to perceive.

Looking for a book that encapsulated the literature of field identification just before BWP, I chose the still worthwhile ‘Frontiers of Bird Identification’ by Macmillan which put together 29 of the major papers published from 1960 to 1977, with postscripts written up to 1980.

Seventeen pens were involved, the most free-flowing mine and the late Peter Grant’s, but in fact the latter’s work and that of the raptor experts Porter, Willis, Christensen and Nielsen were under-represented. The reason was simple; in both cases, their remarkable efforts merited whole new books, each still selling.

Even so, ‘Frontiers’ did adequately show how field characters were perceived at the time that Volume 1 of BWP thudded down in 1980. How well do its statements stand up today?

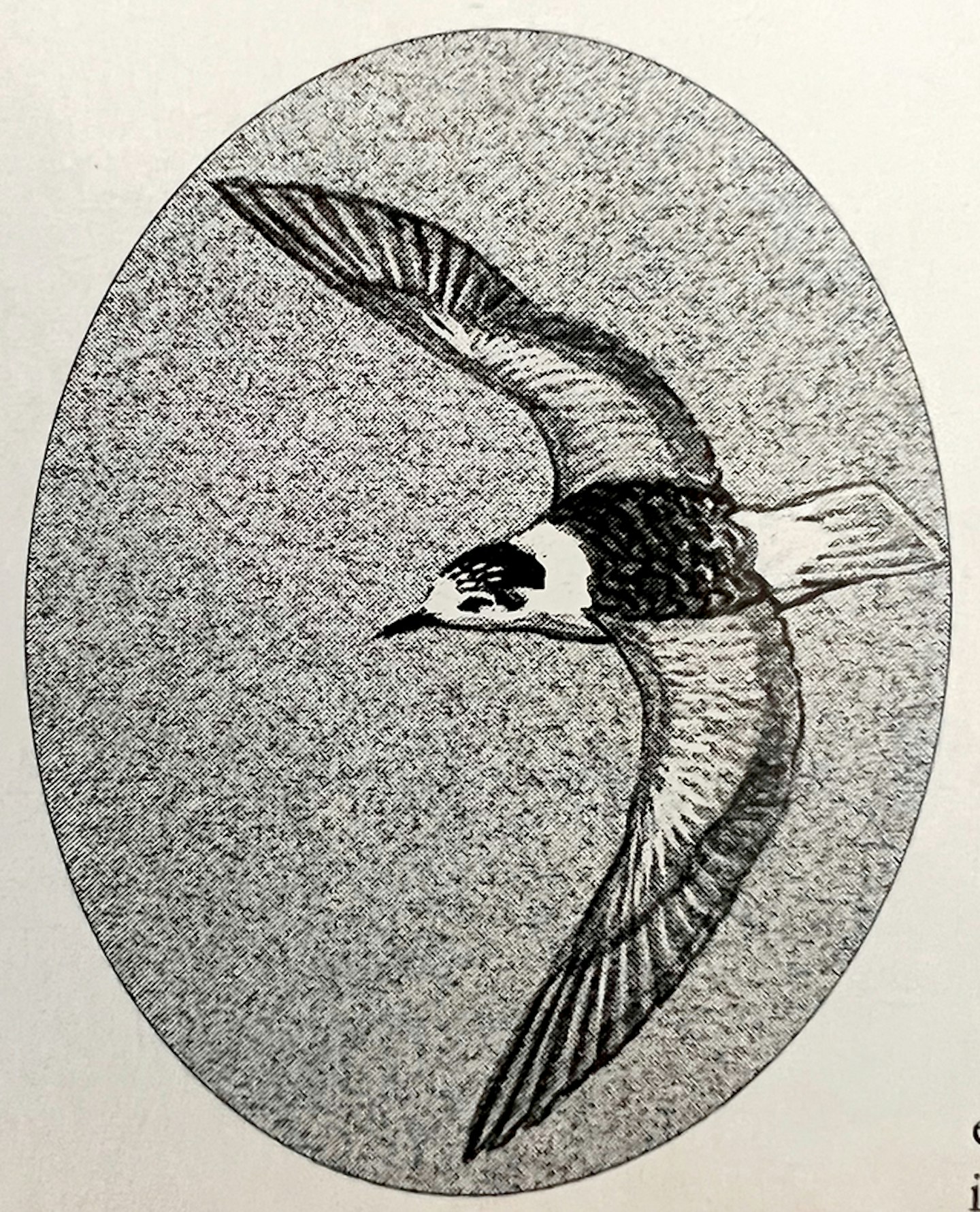

• Ken Williamson’s marsh tern paper took the scales off our eyes on their juvenile dress (but some doubts have arisen on pesky intermediate Black – or is it White-winged Black – Terns).

• Dowitchers remain puzzling. We all seem now to accept that Long-billed can be done on voice, but will the British Birds Rarities Committee (BBRC) ever pronounce on the old Short-billeds? People like me who saw the Cley bird aged 24 are now 58.

• Large pipits have actually got more troublesome. The distinction of Blyth’s from Richard’s may never have a clear script.

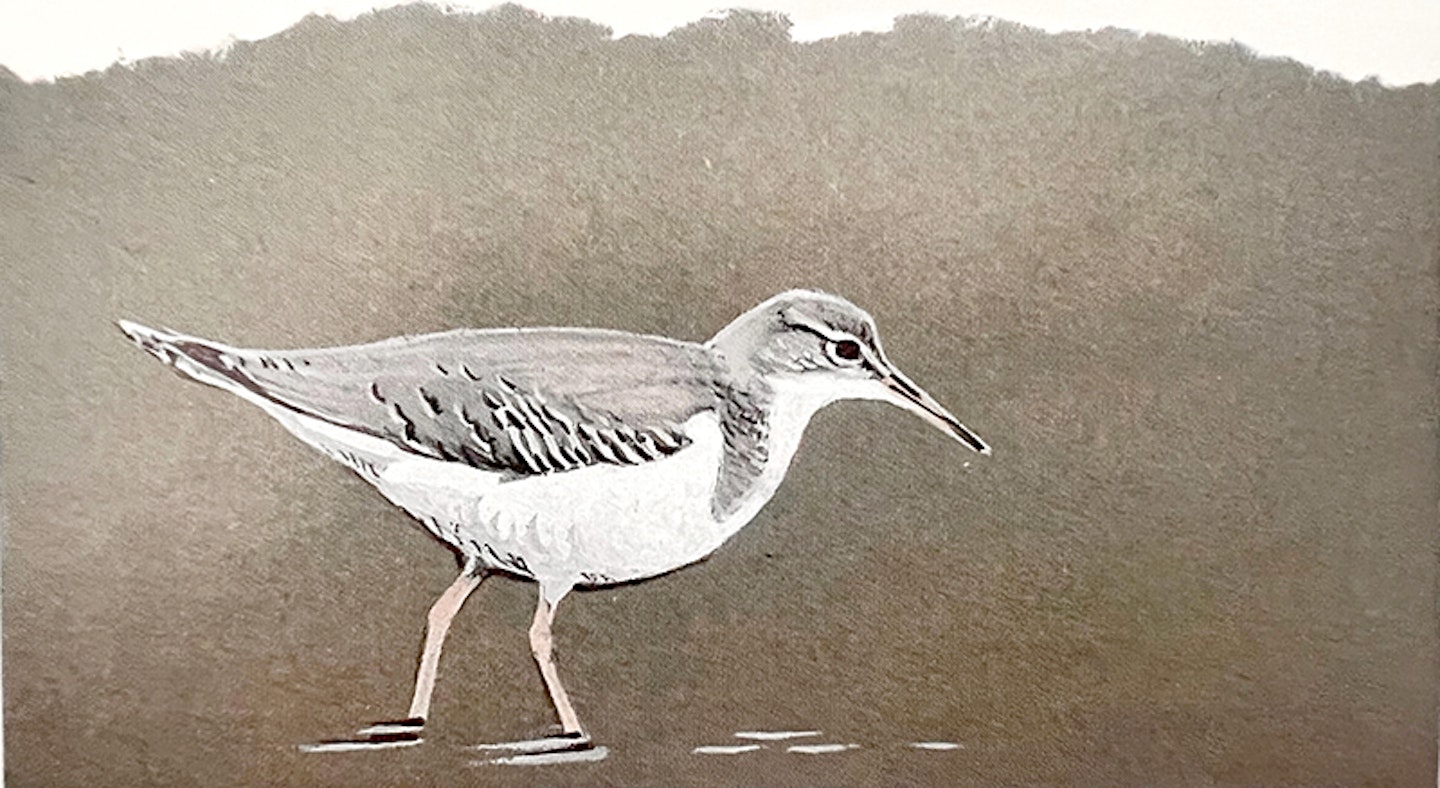

• Retained sub-adult tern plumages have been sussed and the early Spotted Sandpipers were sound (though it took Steve Madge’s eyes to see their short tails).

• Dusky and Radde’s Warblers were properly pronounced to be far from almost identical, ‘contra’ the old ‘Handbook’

• Stints were advanced for proper attention (but only the later artistry of Lars Jonsson took yet more scales off our eyes.We were compelled by him and Peter Grant to inspect covert and tertial fringe colours or die an ignominious death!).

• ‘Commic’ tern wing patterns and the large white winged gulls were worked over well. A useful summary of grey goose forms and looks appeared, courtesy of BWP collaboration.

•The two short-toed larks got their streaks and wing structures sorted. The Tresco Northern Waterthrush took a dreadful hammering from a Canadian and a Dutchman (but the late David Hunt and other Brits hung on through the rounds. The BBRC let it stand.)

• Treecreepers were measured ad nauseam (but it took 16 more years for a taxonomist to spot real plumage differences).

• The wing patterns of two Asio owls were tugged apart (but later an argument over separate measurements versus actual structure showed how very difficult complete perception is).

• The wing pattern of Great Snipe was got wrong and then – courtesy of some Swedish photographs – put right. Pintail Snipe was described (but the swine has not yet arrived, while somewhat oblique and confusing references to Swinhoe’s took seven years to be brought into focus).

•A Sora laid both braves and cowards low. A widespread field guide illustration proved nothing but dangerous. Little and Reed Buntings were firmly separated.

• Siberian Stonechats were put firmly on the map (but BWP reversed the attribution of the two furthest races). Blue-winged and Cinnamon Teals were assessed, but continued to cause problems).

In my not-altogether unbiased opinion, the performance of Frontiers’ can be scored as: Played 24; Replayed 5; Won 13; Drawn 1; Extra time being played 8; and No declared result 2.

Let us move immediately on to the new Field Guide to the Rare Birds of Britain and Europe. Ian Lewington’s paintings dazzled; Per Alstrom’s and Pete Colston’s text glinted with professional comments. Like everybody else, I was very impressed.

One by one, however, the small disappointments came. Incomplete call references; little or no notes on jizz; frequent need for bionic eyes (or lucky mist-net) in the use of ageing characters. A book that had knocked me out at first sight was letting me down on repeated use, for which purpose I had bought it.

So, I decided to give it a stiffer test. I went back to ‘Frontiers’ and tried to see whether in the intervening 12 years the scores on its subject groups had changed for the better.

• Albatrosses (and giant petrels) remain tough; four need bill colours to clinch identification – at sea?! Nothing new on Lesser White-fronted Goose (but useful status notes).

• Good exposé on teal (five duck heads together in one useful drawing worth a thousand words); no mention of black chin streak in young Sora (the St Agnes controversy wasted?).

• Excellent bash at stints, especially the dreaded Red-necked (will BBRC please note and get back to those ‘pended’ immatures of the mid-1970s?): confirmation of voice diagnosis in the dowitchers (but it is also clear that plumage variations will always converge and so confuse); all clear on Spotted Sandpiper.

• Kumlien’s and Thayer’s Gull are declared just races of Iceland (pity, I fancied the latter); super notes on Roseate Tern (almost a rarity now).

• Careful restatements on large pipits (but does Richard’s never utter ‘chup’ notes? What the authors say confidently in one sentence took up a whole anxious paragraph in BWP!); Siberian Stonechats renamed ‘Eastern’ (cheers) but still no investigation of intergrades with European birds (tears).

• No jizz references in Acrocephalus warblers (but nasty evidence of repeated Marsh x Blyth’s Reed hybrids); excellent painting of Booted Warbler (but jizz and lurking small Olivaceous unmentioned); Hume’s Yellow-browed “probably better considered a separate species” (so, what about the apparent intergrades like the Ashby de la Zouch bird?)

• Radde’s painted and written too brown (where is the vivid olive tone of many? See any pic!); Dusky also painted brown (where is the cold greyish tinge that Radde’s never shows?).

• Really helpful though tortuous treatment of the small buntings (special bouquet to the artist for seeing the large bill of Yellow-browed but too few calls given).

Scoring the RBG is difficult but compared to ‘Frontiers’, I make it something like: Replayed 18; Won 8; Extra time still being played 6; Goals missed 2; Own goal 1; and Opposition changed jerseys 1.

This may seem a rather harsh partial verdict on what is a truly tremendous team effort but it just goes to show that the achievement of ‘final clinchers’ in field identification is neither an easy nor a short process. As the late, great Horace Alexander remarked in my teenage, some birds are likely to humble their observers for ever!

I have no doubt that new perceptions are widespread but fail to get into common usage because they are not conveyed to others in easy words and figures.

In describing the distinctive call of Blyth’s Pipit with seven (two conflicting) adjectives, the new book will only promote migraine pills. Going on and on about the ventral barring of juvenile skuas will not convey the slinking look of the Pine Marten-like Long-tailed nor the gull-like flight of the Wolverine-aping Pomarine. One more diatribe on skua feather patterns and it could be the funny farm for me!

Beware artistic licence

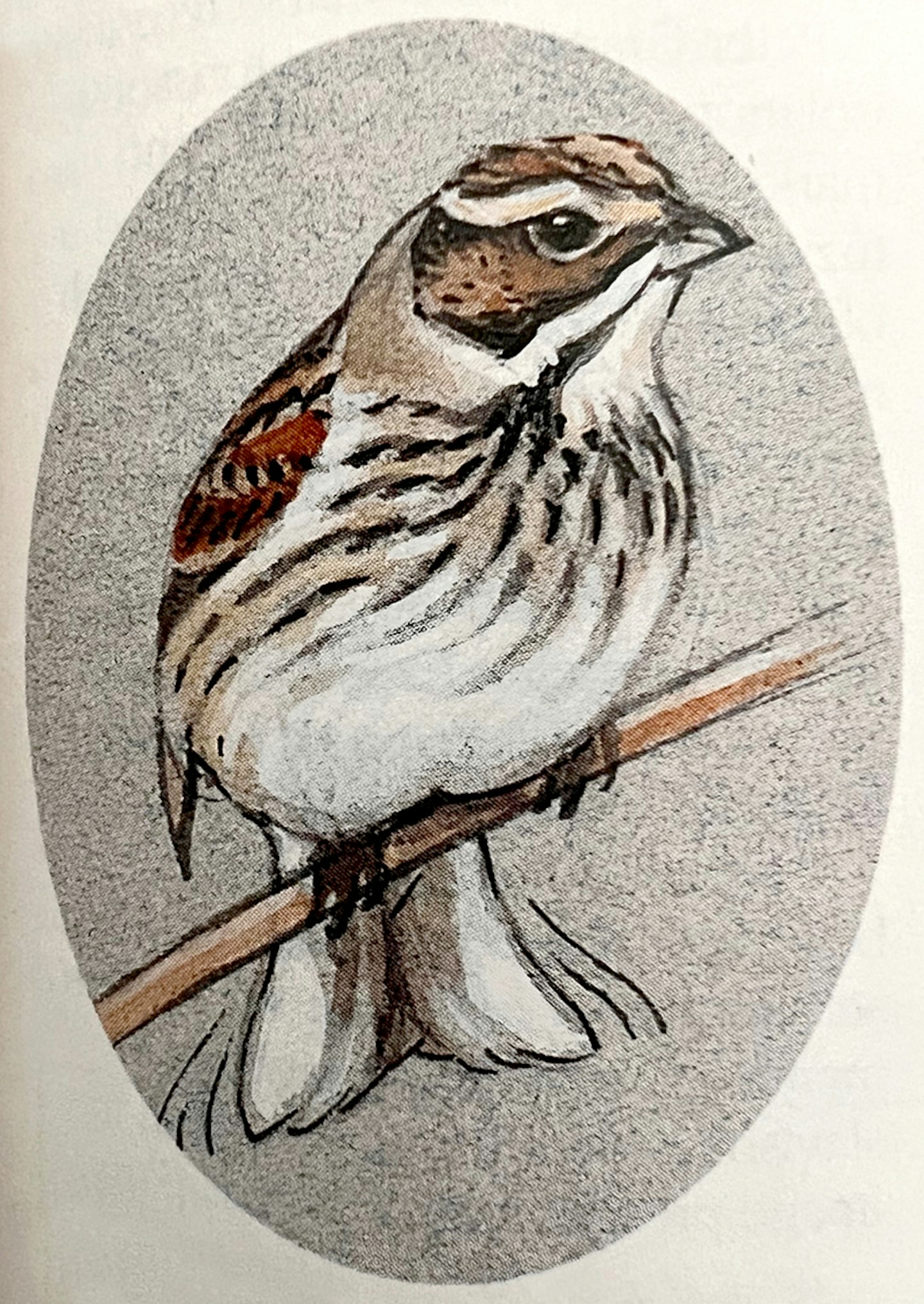

We also have to recognise the foibles of the illustrators when assessing the value of field guides – even our personal favourites. The late Noel Cusa was a limpid water-colourist but most of his flying birds would have fallen down.

Lars Jonsson has marvellous vision and a way with feather contours that turns me green. His birds truly live, but why are they all so plump? Peter Hayman’s command of detail is truly astonishing, but his training in architecture shows.

Alan Harris is superb with plumage tones but does he see all those tiny but telling differences in character? Ian Lewington’s plumage textures are awe-inspiring, but are his palette colours a bit rich? Or, did the printers of Rare Birds of Britain and Europe’ overdo the magenta?

After all my struggles with pencil, pen and particularly brush, I “know it ain’t easy” and I have nothing but admiration for those who do it better. Even so, I have to advise you to learn how to allow for the variations in perception in the identification literature. Every time you see its subjects alive and flicking, you are on your own. ‘See for yourself is a golden rule.

Steer your own course

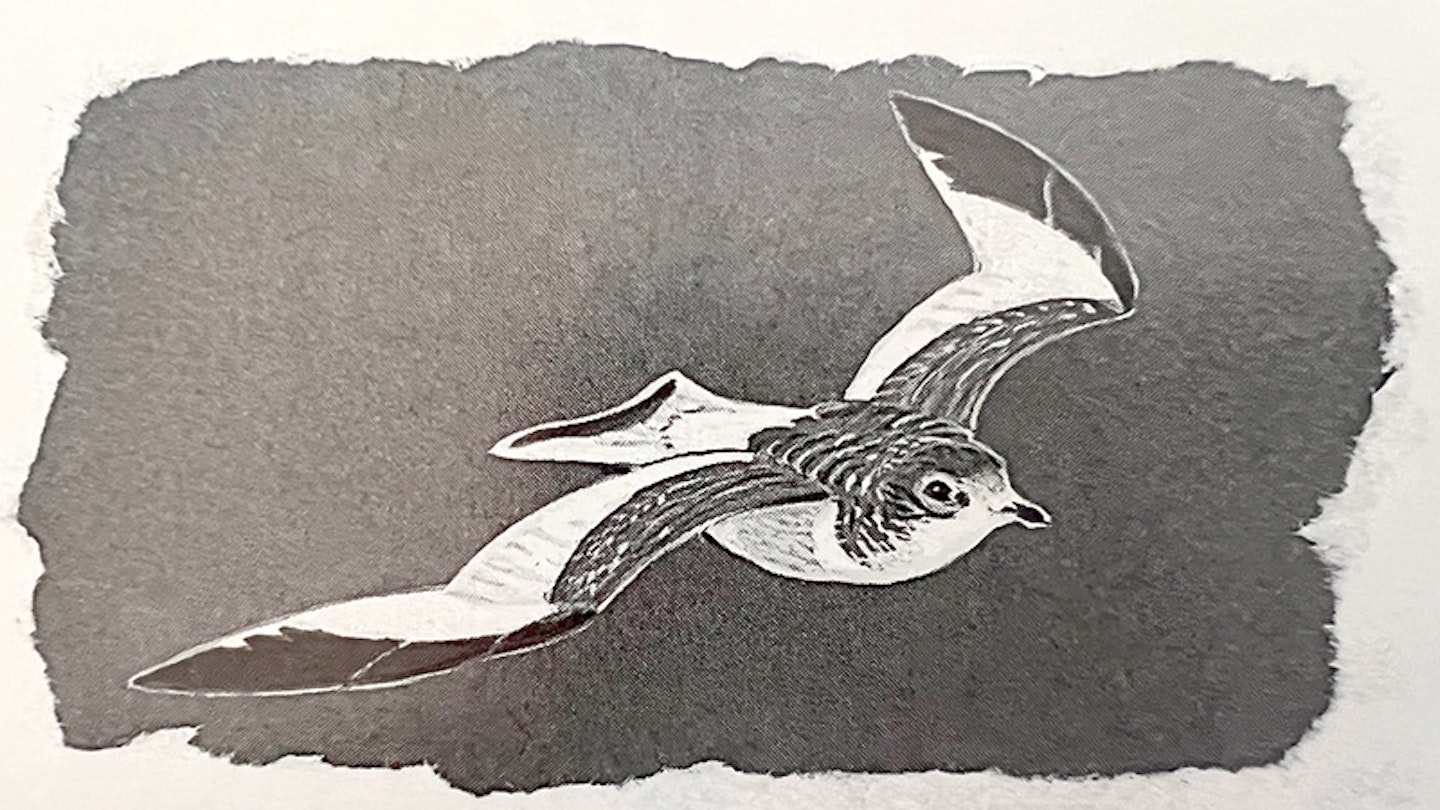

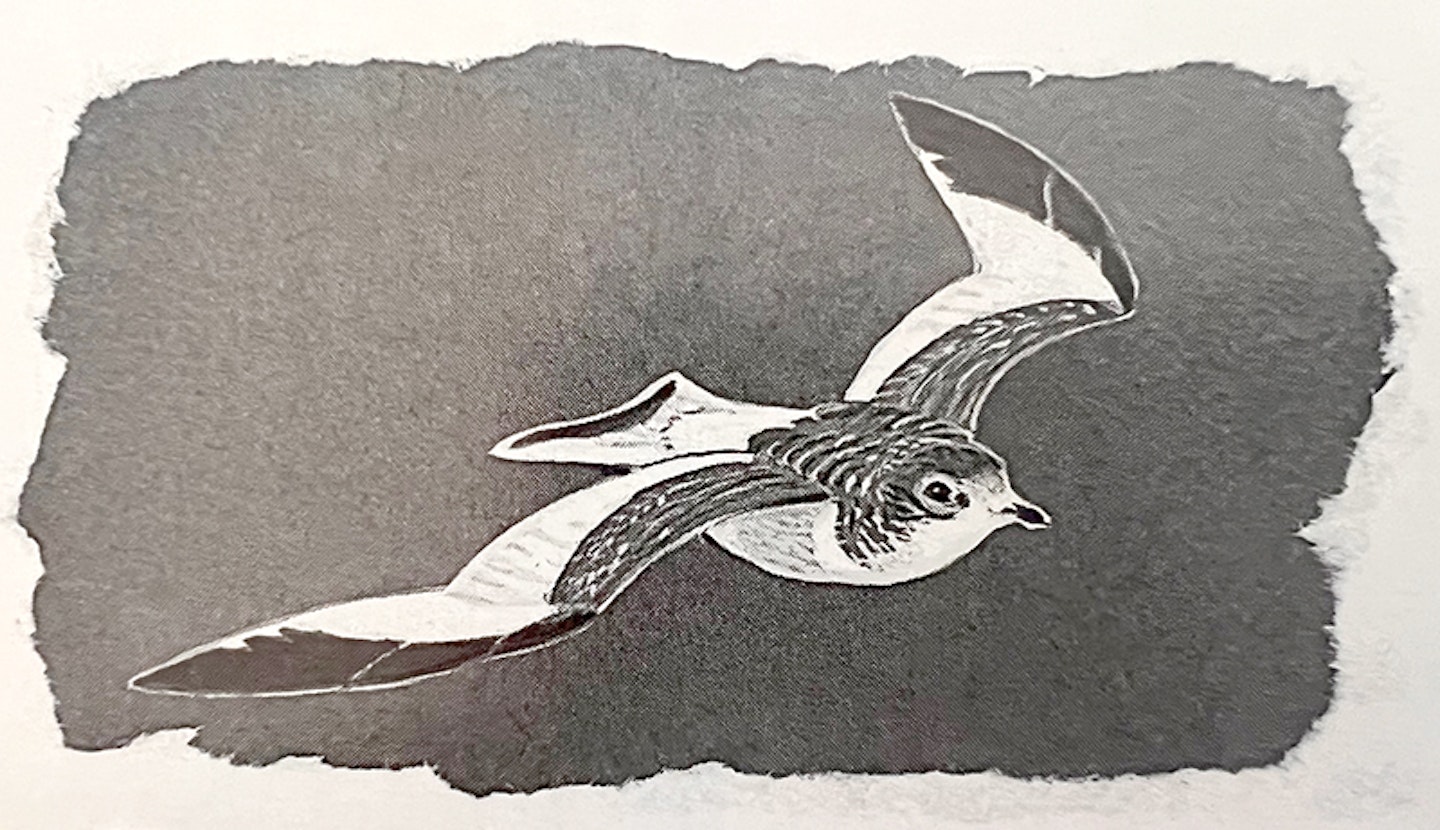

To avoid cloning in field identification, it is also important to join in its seminal moments of confidence-building. The dark saddle of the juvenile White-winged Black Tern had been fully portrayed by George Lodge, the Handbook artist, but it was Ken Williamson who forced the point home and raised our sights on marsh terns.

Peter Grant’s and Lars Jonsson’s isolation of the few crucial stint marks, Mike Densley’s slightly fuzzy but totally telling photograph of Pallas’s Grasshopper Warbler’s resemblance to Sedge and ocean-wanderer Bill Curtis’s repeated experience of tubenoses (re-expressed confidently in the East Riding) are other examples of the boosts that have allowed advances in identification practice.

Understanding these moments, better still sharing in them, could set you up for a lifetime of increasing perception, not just slavish re-identification through the image prescription of a third party.

Irrelevant ID topics

Be aware, too, of the thunderingly non-seminal moments in the identification literature. The mind-bogging (boggling is too good a word) debate on size illusion; the irrelevance of the nearly always hidden humeral feathers (to any identification); the persistent trauma hanging over eastern Chiffchaffs, Greenish and Arctic Warblers (now to be compounded by the lumping of both Green and Two-barred Greenish into the second?); the shambles of the crossbills; and the occasional sallies of the gratuitous “can’t be that or there” school of long-distance squelchers are the examples that come quickest to my mind.

When are the slingers of mud at winter Sabine’s Gulls going to acknowledge the now annual records that show the Handbook was right after all? Eilat and California have a lot to offer but the identification of birds in the North Sea is best done on site.

Can you make a contribution?

Beware also the lack of complete resolution of characters. Take tail-cocking, wing-flicking and like actions in small passerines. These are clearly diagnostic in a few species and may be so in many more, but can we be sure?

This kind of uncertainty brings me back to my main complaint in this vexed commentary, the seemingly diminishing ability of observers to see birds as whole beings. When starting out on the passerine volumes of BWP, I analysed with some care the types of field characters that were under-expressed in the literature.

These fell largely into what we now call jizz, and included relative size, structural proportions, flight action, variations in gait, posture and ‘nervous’ movements. I also thought that differences in escape flights, flock shapes, most frequent companions and other clues of association might bear fruit. A letter asking if other observers felt these were valuable was published in British Birds. Not one answer did it get!

As the oldest UK bird journal has now lost its monopoly on criteria, a new free-for-all in character publication and dissemination has appeared. I do not weep for the loss of the party line but we must take care not to throw away all sense of responsibility or continuity of expression.

With literally thousands of ‘rare men’ (and for all I know, ‘rare women’, too) in the field today, where there was in the late 1950s supposed to be only 10, literally millions of acute perceptions are being stored in clever brains.

I know that any keen observer still has the potential to contribute personally to the identification literature. It was the sum of individual perceptions that so marked the old ‘Handbook’ texts and in spite of some cautionary editing, I have tried to keep a degree of singular interpretation alive in the BWP Field Characters. The balanced view of a committee may be safe but is it not also inevitably diffused?

There is so much that sharp eyes, imagination and questioning minds can still add. Just one day in a British wetland and another at the Albufera in Mallorca could end the uncertainty about tail-cocking in Sedge and Moustached Warblers. A few hours at Tring could tell us more about ‘half-eastern’ Stonechats, or at least point to where we should go to see if they exist.

So, in spite of the plethora of field guides (eight out of 34 ornithological titles in W.H. Smith’s in Burton-on-Trent when I last looked), the splendid new genre of identification monographs and the stream of notes in BB, Birding World, Dutch Birding and the like, we are still a long way from instant boredom in front of a difficult bird.

Why not pick yourself at least a small hill in field identification and climb it? Your view from the top might well help us all. Happiness is your own perception of another being. Their eyes or your own?