April 1992

Love at first site!

Birds are definitely not equal when it comes to human appeal and interest – everyone has a favourite. Ian Wallace reviews the world of the small, feathered dinosaurs and discusses his own chart-toppers.

Every birdwatcher or bird lover I know has favourites. The paths of Ron Johns – almost 500 ticks in Britain and counting – and me – only just through 400 and ceased chasing – rarely cross these days but I shall never forget how much he would praise the common, but always urgent, Redwing.

Indeed, it scored so highly with Ron that when I ushered him to his first Red-eyed Vireo on St Agnes in October 1968, he was sufficiently unentranced by it to comment: “What a boring bird, not a patch on Redwing”. In my view, it is not degree of rarity nor accident of vagrancy that makes particular birds a cut above the ordinary. It is their personal style and element of intrigue.

Going through my earliest experiences with birds, I find the sequence of my initial fancies, to have been Tystie (Black Guillemot), because of Shetland summers in the late 1930s, grey geese (due to Sir Peter Scott’s two evocative books “Morning Flight” and “Dawn Chorus”), sea ducks (courtesy of the once nutritious sewer that supported thousands at Seafield, near Edinburgh), Bonxie (Great Skua), from Shetland again, and Lapland Bunting (due to an evocative photograph in T.A. Coward’s “Birds of the British Isles”).

Of these, my deepest fascination was with the geese, which I rarely saw, being ignorant of their winter distribution and habits. This situation did not change until 1947 when I was at a school east of Edinburgh – and right under the autumn flight path of incoming Pinkfeet.

At long last, the months of September and October presented not just rugger but also the longed-for shouting skeins that Sir Peter’s paintings had etched in my mind. When flying into a strong headwind, they would skim low over the school and disturb my Greek and Latin no end.

So moved was I by their exciting passage that, for the first time, my log departed from bird names and aseptic counts and arrived at the purple prose I still indulge in.

It took me 20 years to find a proper goose ground and work it hard. My career moves decreed it would be the marvellous New Grounds (misnamed Slimbridge by most) and the main species was Whitefront, not the Lothian mosses and Pinkfoot of my youth.

For a time, I tried to stay loyal to the latter (because of its presumed Scottishness) but after three winters of Whitefronts, I had to concede they were, for me, the best grey geese. They still are.

The Whitefront’s combination of more-variegated plumage, merrier voice, nimbler flight and its sporting of a Greenland race give it a distinct advantage. Its ability to transport the even more delectable Lesser Whitefront and Red-breasted allows it to break the tape in my goose race.

I still feel guilty about demoting the Pinkfoot but all it does is to look prettier than Bean and carry the odd Barnacle.

Musing upon my infidelity, I wondered what other fancies I had had over my five decades in the field and which, in particular, had either given great excitement or delivered trenchant lessons Or, even better, done both! So I scanned my 40 surviving diaries and found that the “cut above the ordinary” factor had operated on more than grey geese.

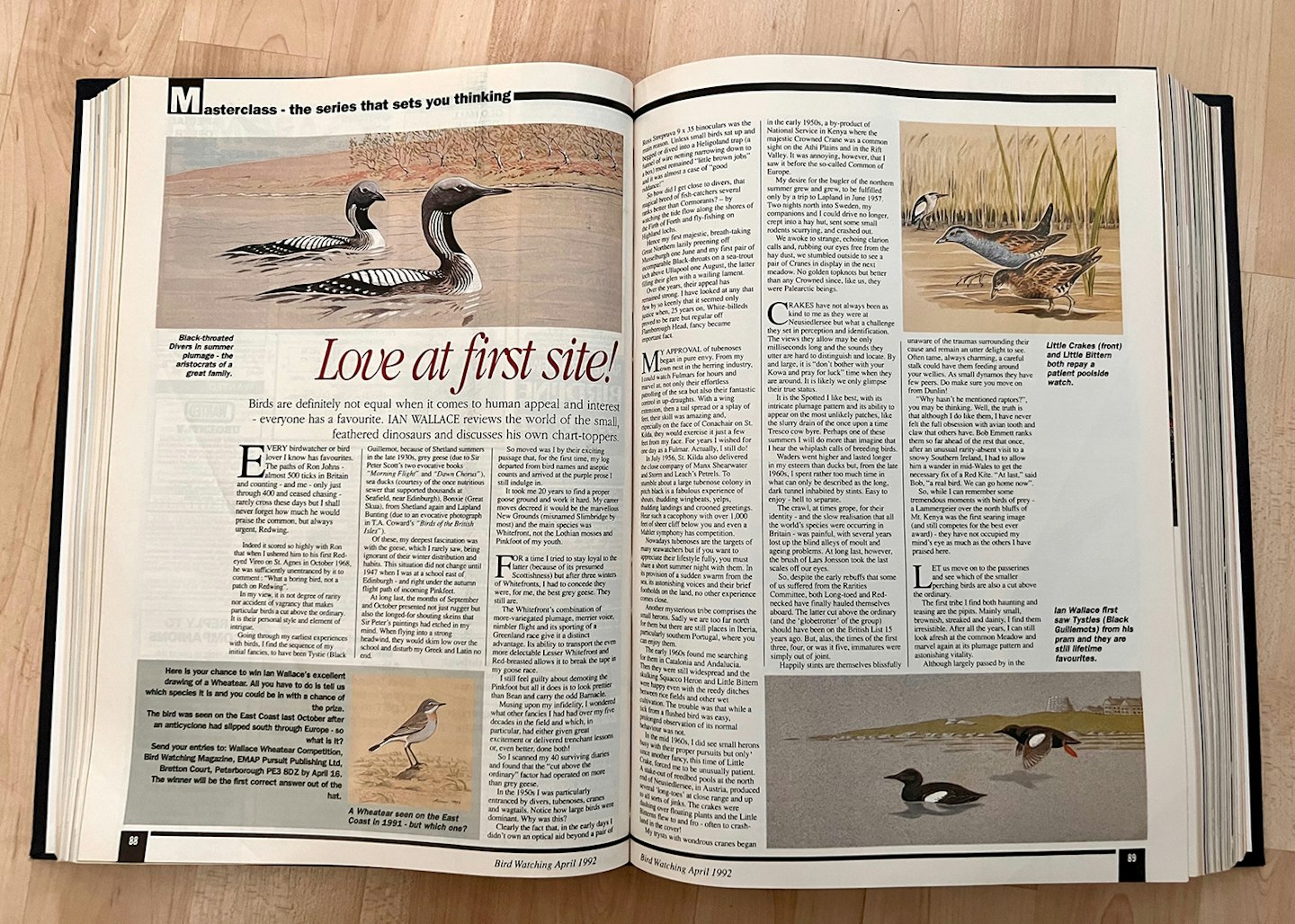

In the 1950s I was particularly entranced by divers, tubenoses, cranes and wagtails. Notice how large birds were dominant. Why was this?

Clearly the fact that, in the early days I didn’t own an optical aid beyond a pair of Ross Strepruva 9x35 binoculars was the main reason. Unless small birds sat up and begged or dived into a Heligoland trap (a funnel of wire netting narrowing down to a box) most remained “little brown jobs” and it was almost a case of “good riddance!”

So how did I get close to divers, that magical breed of fish-catchers several ranks better than Cormorants? By watching the tide flow along the shores of the Firth of Forth and fly-fishing on Highland lochs. Hence my first majestic, breath-taking Great Northern lazily preening off Musselburgh one June and my first pair of incomparable Black-throats on a sea-trout loch above Ullapool one August, the latter filling their glen with a wailing lament.

Over the years, their appeal has remained strong. I have looked at any that flew by so keenly that it seemed only justice when, 25 years on, White-billeds proved to be rare but regular off Flamborough Head, fancy became important fact.

My approval of tubenoses began in pure envy. From my own nest in the Herring industry, I could watch Fulmars for hours and marvel at, not only their effortless patrolling of the sea but also their fantastic control in up-draughts. With a wing extension, then a tail spread or a splay of feet, their skill was amazing and, especially on the face of Conachair on St. Kilda, they would exercise it just a few feet from my face. For years I wished for one day as a Fulmar. Actually, I still do!

In July 1956, St Kilda also delivered the close company of Manx Shearwater and Storm and Leach’s Petrels. To stumble about a large tubenose colony in pitch black is a fabulous experience of shouts, thudding wingbeats, yelps, thudding landings and crooned greetings.

Hear such a cacophony with more than 1,000 feet of sheer cliff below you and even a Mahler symphony has competition.

Nowadays, tubenoses are the targets of many seawatchers, but if you want to appreciate their lifestyle fully, you must share a short summer night with them. In its provision of a sudden swarm from the sea, its astonishing voices and their brief footholds on the land, no other experience comes close.

Another mysterious tribe comprises the small herons. Sadly we are too far north for them but there are still places in Iberia, particularly southern Portugal, where you can enjoy them. The early 1960s found me searching for them in Catalonia and Andalucia.

Then they were still widespread and the skulking Squacco Heron and Little Bittern were happy even with the reedy ditches between rice fields and other wet cultivation. The trouble was that while a tick from a flushed bird was easy, prolonged observation of its normal behaviour was not.

In the mid 1960s, I did see small heron busy with their proper pursuits, but only since another fancy, this time of Little Crake, forced me to be unusually patient.

A stake-out of reedbed pools at the north end of Neusiedlersee, in Austria, produced several ‘long-toes’ at close range and up to all sorts of jinks. The crakes were dashing over floating plants and the Little Bitterns flew to and fro – often to crash-land in the cover!

My trysts with wondrous cranes began in the early 1950s, a by-product of National Service in Kenya where the majestic Crowned Crane was a common sight on the Athi Plains and in the Rift Valley. It was annoying, however, that I saw it before the so-called ‘Common’ of Europe.

My desire for the bugler of the northern summer grew and grew, to be fulfilled only by a trip to Lapland in June 1957.

Two nights north into Sweden, my companions and I could drive no longer, crept into a hay hut, sent some small rodents scurrying, and crashed out. We awoke to strange, echoing clarion calls and, rubbing our eyes free from the hay dust, we stumbled outside to see a pair of Cranes in display in the next meadow. No golden topknots but better than any Crowned since, like us, they were Palearctic beings.

Crakes have not always been as kind to me as they were at Neusiedlersee but what a challenge they set in perception and identification. The views they allow may be only milliseconds long and the sounds they utter are hard to distinguish and locate.

By and large, it is “don’t bother with your Kowa and pray for luck” time when they are around. It is likely we only glimpse their true status.

It is the Spotted I like best, with its intricate plumage pattern and its ability to appear on the most unlikely patches, like the slurry drain of the once upon a time Tresco cow byre. Perhaps one of these summers I will do more than imagine that I hear the whiplash calls of breeding birds.

Waders went higher and lasted longer in my esteem than ducks but, from the late 1960s, I spent rather too much time in what can only be described as the long, dark tunnel inhabited by stints. Easy to enjoy – Hell to separate.

The crawl, at times grope, for their identity – and the slow realisation that all the world’s species were occurring in Britain – was painful, with several years lost up the blind alleys of moult and ageing problems. At long last, however, the brush of Lars Jonsson took the last scales off our eyes.

So, despite the early rebuffs that some of us suffered from the Rarities Committee, both Long-toed and Red-necked have finally hauled themselves aboard. The latter cut above the ordinary (and the ‘globetrotter’ of the group) should have been on the British List 15 years ago. But, alas, the times of the first three, four, or was it five, immatures were simply out of joint.

Happily, stints are themselves blissfully unaware of the traumas surrounding their cause and remain an utter delight to see.

Often tame, always charming, a careful stalk could have them feeding around your wellies. As small dynamos they have few peers. Do make sure you move on from Dunlin!

“Why hasn’t he mentioned raptors?” you may be thinking. Well, the truth is that although I do like them, I have never felt the full obsession with avian tooth and claw that others have. Bob Emmett ranks them so far ahead of the rest that once, after an unusual rarity-absent visit to a snowy southern Ireland, I had to allow him a wander in mid-Wales to get the necessary fix of a Red Kite. “At last.” said Bob, “a real bird. We can go home now”

So, while I can remember some tremendous moments with birds of prey – a Lammergeier over the north bluffs of Mt Kenya was the first searing image (and still competes for the best ever award) – they have not occupied my mind’s eye as much as the others I have praised here.

Let us move on to the passerines and see which of the smaller perching birds are also a cut above the ordinary. The first tribe I find both haunting and teasing are the pipits. Mainly small brownish, streaked and dainty, I find them irresistible. After all the years, I can still look afresh at the common Meadow and marvel again at its plumage pattern and astonishing vitality.

Although largely passed by in the modern dash for rarities, the lowly Meadow is one of the most telling signals of life’s natural rhythm. I expect it to show me the beginning of spring and the ending of autumn. I also look to it to bring me other exciting relatives. The early Red-throateds on St Agnes seemed to ride on the backs of big Meadow passages.

Up hill, down dale, the commonest pipit is a favourite with me.

At one time, I thought of the Tree in similar terms. Indeed, as a carrier of rarer cousins, I rate it above Meadow. But, at least in my round, it has become a remarkably scarce bird. In two recent autumns I have encountered more so-called rare pipits than Trees. In conservation terms, a bright red light is on.

Shrikes are markedly raptorial passerines and I have to own to being obsessive about them. Having somehow seen Great Grey before Red-backed and learnt of them most in Kenya and the Middle East, I cannot look at them without experiencing huge bouts of nostalgia.

As frequent silhouettes in savannah and desert, their images stand out like no other passerine migrants. For me, the sight of the odd British straggler fails to convey the family’s true presence. It is well worth travel cost to see the mass shrike movements that bring the spring migration of African wintering species to an end in middle latitudes.

I have already admitted to hard times with warblers. A decade’s struggle with the Hippolais and up to 20-year waits for my first Yellow-browed and Pallas’s passed slowly. These days the birdlines can deliver a smart end to such frustrations for everyone but it still appears that warblers are cuts above the ordinary for most observers. Certainly, their magic has not dimmed for me and there is nothing better than the close views a patient stalk or wait can produce from a few grams of brain, brawn and feathers that have flown up to 4,000 miles. Miraculous is the only word for that!

If I am honest, however, the wheatears will win any passerine contest for my special attention. Still a real challenge in field identification – in at least three species pairs – and at times distinctly flighty, they are my favourite adrenalin-boosters. Every last one is worth a second look.

I particularly like the suddenness of wheatears. A flash of white arse, a bouncing pitch, another wink of white, a head bob, a flex of the legs, and so on. Northern only? Or something better? Will it give a second view?

You are not always onto a winner – but there’s always a chance! Like the Meadow Pipit, the Northern Wheatear is a true omen of the turning year. I thank it for visiting my current study area for eight months of most years. However much I feel land-locked in Staffordshire, it can remind me, in an instant, of the high wilderness from Greenland to the Bering Strait. This is another common bird of untrammelled greatness.

Next for me come the buntings, a tribe that has lacked the fawning press accorded other passerines but which is nonetheless fascinating and irrepressibly sneaky. I like the way they can shatter my calm and leave it broken as they leave the immediate landscape. What teases they are.

As with pipits and wheatears, the common species often carry the rarer ones. For many years I have found it impossible not to look through every bunting party that crossed my path. By such persistence, I have produced cross-country Laplands and Littles in two Midland counties and winter vagrant Cirls in my last three study areas (all north of Birmingham). This product of quite frequent cuts above the ordinary is in distinct contrast to that presented by finch flocks which have, for me, provided far less variety.

Yet I have to give two sets of finches the last two places in my roll of honour-cum-delight. These are the redpolls and the crossbills. However common in some years or areas, they always feel unusual. Better still, they are systematically untidy with their identification. And it is a matter of continuing debate and still a challenge after more than 200 years of description!

So, every time a flock appears, it is always full stop and total concentration’ time. Are the birds just Lesser Redpolls or Common Crossbills? The respective alternative is firstly at least two other races or another species and secondly three other species. What more options do you need for birdwatching that is a cut above the ordinary?

Excuse me, but I think I’ll go out and try for one of my favourites right now!