February 1992

The magic of trees

Continuing his sallies into the less obvious ways to birdwatch, Ian Wallace considers trees as green beings and tells you which, in his experience, have been the best for birds.

Down the lane from my village is a cottage with greenhouses and a noticeboard advertisingeverything home-made from delicious chutney to Madeira cake.

The cottage is called “Forty Shades” and after we had made several purchases there, I was forward enough to ask why such a name? “Because the wooded hill opposite has that many shades of green on it in spring” was the engaging reply of the husband of the cook.

Green is the main part of the magic of trees. So beautifully and so intensely possessed of it, they give refreshment to the human beholder by varying the classic colour of rest almost infinitely from May to October. Then, they dispel it through a tumbling kaleidoscope of reds, browns and yellows.

Look more closely at trees and you will see another miracle. Each species has a shape, a structure of its own, both in leaf and out. Within this arboreal form of jizz, there is another, infinitely variable, set of trunks, branches and twigs whose patterns are as fascinating as all those shades of green.

The beauty of trees and their individuality as green beings took a long time to get through to me but one morning, in the Spey Valley in the late Spring of 1976, I found myself suddenly transfixed by the tracery of some broadleaf canopy and the light shining through it. The trance of that moment has never quite left me.

As I write this from my upstairs study, on a frosty December day, I can look out of the window and enjoy the forms of 15 species of tree. Furthermore, their colours are not at an end. The trunk of my skyline Ash is a clearer grey than those of its two oak neighbours and my birch now shows again the amazing purple tone of its outer twigs.

In an instant my memory brings up inner pictures of the birch forests of the Western Highlands and the blaze of purple and brown madder they present in winter sunlight. Thank the Lord for trees. They are never boring and have the excellent habit of not flying away!

Willow and pine

Trees are, however, even more enjoyable when they attract a lot of birds. It is worth some study time to know which these are. It is surprising how few British birds have names which indicate directly or indirectly their association with trees. Twelve is a short list and only two tribes of tree are clearly named, the willow and pine.

The most classic tree-cum-bird name is Willow Warbler. Although it is actually the most ubiquitous arboreal species of Eurasia, it and Chiffchaff often inhabit willows in preference to all other trees when on migration. Small wonder these two very similar species were thought to be just one until Gilbert White listened to their strikingly different songs.

I first noted the close association of migrant leaf warblers (English name for the genus Phylloscopus) with willows in Regent’s Park, London, 40 years ago. On spring passage and again in autumn, more than 80% of my sightings came from the willows which screened the lake edge and islands and dotted the north-west quarter of the park.

In other areas, I have not found the draw of willows quite as strong as in city parks but everywhere they remain a tree tribe worthy of search. One of the best places in which to enjoy their autumn visitors is the woodland that stretches from Wells to west of Holkham along the north Norfolk coast.

Along the southern edges of the conifer belt are clumps of deciduous trees and the sallows among them are often tenanted by a marvellous variety of warblers and crests. Because their leaves are small, even tiny birds show well among them and a “wait and see” by a thicket is rarely without thrill and close view.

For those of you who may now fancy a willow in your garden, one word of warning. Take care to plant one of the smaller species. As Tony Soper has observed, the Pussy Willow has “everything to commend it... warblers, tits and Goldcrests make a beeline for it”

Oaks and Hawthorn

When I worked Regent’s Park four decades ago, I noticed two other tribes of tree were often full of migrant birds. The first was the oak, particularly the Durmast or Sessile species which is more erect (and easier to look into!) than the familiar, rugged, gnarled and irregularly spreading, Pedunculate form – the original ‘ships’ timber’. (Sessile and Pedunculate Oaks differ mainly in the ways in which their leaves, flowers and acorns are attached. Sessile Oaks have long-stalked leaves whereas the leaves of Pedunculate Oaks are stalkless. In each case the reverse is true for flowers and acorns).

The birds the Sessile Oak most magnetised were British-bred Pied Flycatchers which moved through in mid-August, before the odd drift migrant in September.

The third best bird trees in the park were the Hawthorns. Long before they were red-berried in autumn, their tight canopies played host to many birds. If I was after migrant Goldcrests, it was in the Hawthorn foliage that I usually found them. The reason for their presence was the trees’ ability to sustain invertebrate food all year.

Source of food

This last point is the crux of bird and tree associations. It is the trees which present diverse food sources that attract the most birds. These may be on the tree, within the corrugations of bark, leaves, catkins and fruit, or eventually fall off it, as nuts and seeds do. Inevitably, the food sources vary by season and it is well worth your time to understand the span and cycle of tree food productivity.

For example, oaks can support more than 300 insect species and produce the late spring and summer crop of caterpillars essential to high-breeding success in tits and warblers. Willows may harbour up to 250 small creeping things, birch 225 and Hawthorn 150. These species all constitute preferred, fast-protein sources for insectivorous birds. The last two go one better by also presenting excellent vegetable food stores in autumn and winter.

Watching birds forage in trees will show you the differences in tree food availability. The last pear tree of my village’s former perry orchard happens to be in my back garden. Even on the hardest winter day, its crusted bark attracts birds and, evidently, they find some mite or other. In full leaf, it is constantly harvested.

Yet the two flowering cherries which brighten up my front patch are rarely searched or even perched upon. Small wonder: it’s the pear which has produced a list of 33 species. The cherries have struggled to reach seven!

Guidance on tree and bird associations is barely available in field guides or from birdlines. You can find it, however, in the habitat sections of any good handbook or bird atlas and particularly in Tony Soper’s ‘Birds in Your Garden’, published in 1989.

Sycamores and birches

Returning to my own special trees, I have to mention the Sycamore. It is no favourite of gardeners and it has been said to be of limited value to birds. My friends at island and coastal watchpoints would not agree. Particularly in late autumn, the canopies of Sycamores can be the most magic of green or yellowing places. Ignore them at your peril.

Unfortunately Sycamore leaves are large and when the canopies are densely layered, it is often difficult to see more than the odd, flitting shape. Witness Flamborough Head’s elusive Red-flanked Bluetail, last autumn.

From mid-October, however, the leaves fall rapidly and as they thin out, the gems appear. Of my 20-odd Pallas’s Warblers away from Siberia, all but three have been in Sycamore. Need I say more!

Because the birch was so often the only common, broad-leafed tree in my Scottish youth, I am very fond of it. It comes in three main forms, the well-known Silver, the White and the Dwarf. Their high insect count I have already indicated, but they also produce free-flowing sap and nutlets. The nutlets make up a favourite food of immigrant northern redpolls, which are specifically adapted to it given their breeding niche in the white taiga of northern Eurasia. Heavily seeding birches should not be passed by in autumn and winter.

In my East Riding study area, I learnt to inspect closely the nutlet debris below birches. If it had fallen in a haze of small, shredded pieces – rather like dry brown snow – I came to know that small, hungry finches were not far off. Back to the car for a fast scan of even roadside birches and, in four winters out of seven, I was soon into the thrilling tease of a redpoll swarm. Just once, but unforgettably, two members were roaring, white Arctics.

Alder and Hornbeam

Closely related to the birches are the Alder and the Hornbeam. I like the former a lot. Its presence tells of wet land and its linear distribution along the streams and rivers makes it easy to search. Its fruit catkins look rather like small pine cones and are swarmed on by the prettiest of our small finches, the Siskin. In my current study area, it could well be named ‘Alderfinch’. Of more than 300 bird/days, only seven have come from other trees!

The Hornbeam is a tree I find hard to work. Regent’s Park’s one clump always held Greenfinches in winter, only yards from streaming traffic. But I have yet to find the Hornbeam wood full of Hawfinches, so vaunted by other authors.

I am less sure about the associations of birds and coniferous trees. My favourites are the sparsely-foliaged Larches which wear the softest greens of all conifers in spring and have tiny exquisite flowers. They attract tits and finches all year. Although not natives, there are no better trees than Larches for seeing and hearing Coal Tits, the best of a bright family in my opinion, and if you want another go at Siskins and redpolls, Larches come highly-recommended.

The avian inhabitants of the more densely-leaved (and permanently-cloaked) conifers are far more difficult to observe. Close, patient watches of wood edges, sunlit canopy holes and ripe cones are essential to success.

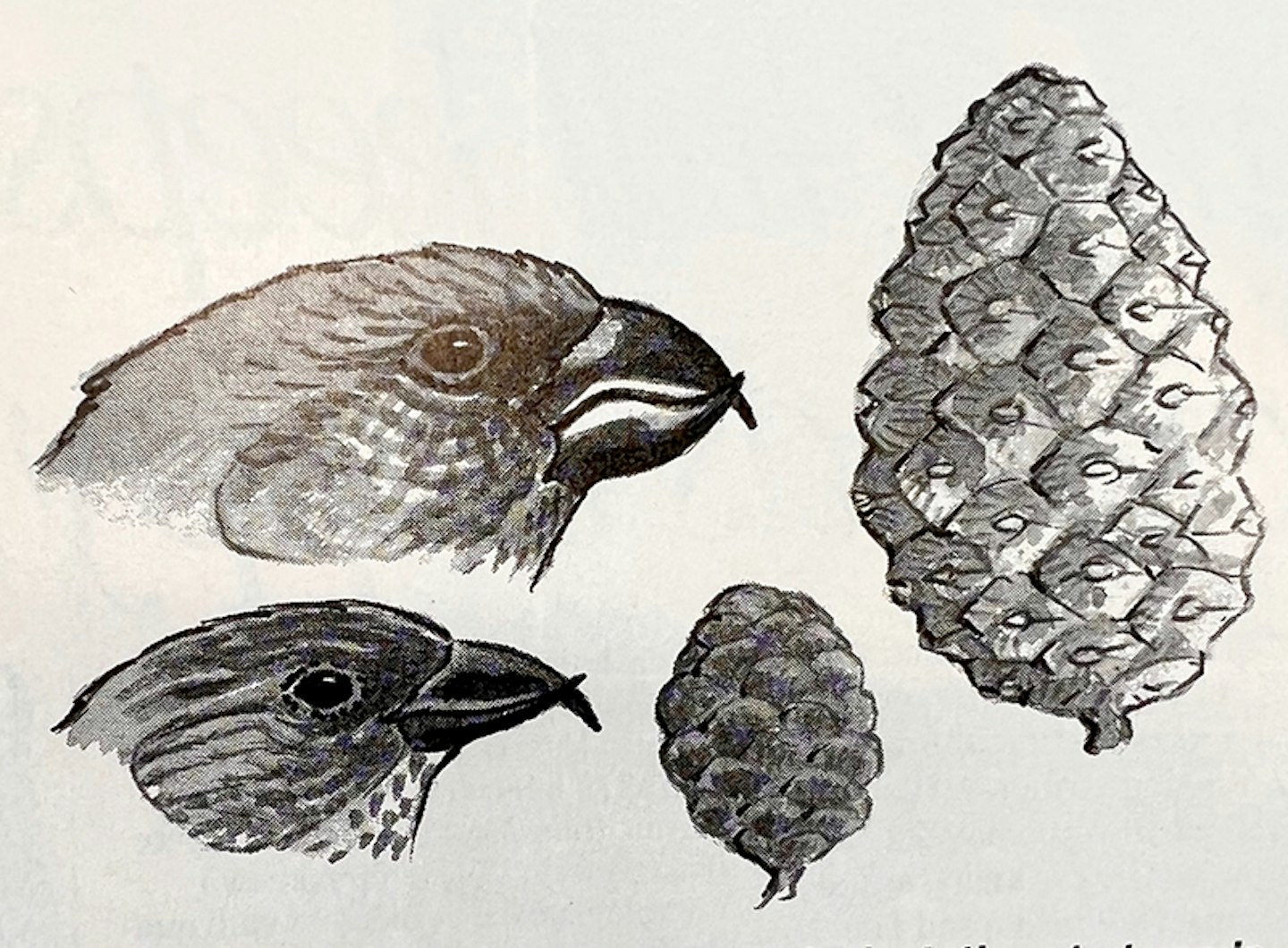

My favourite targets are the most ebullient of all finch clans, the crossbills. Possessed (happily) of ringing voices, they are regularly easy to hear but very difficult to see. These days we are expected to distinguish four species, the Parrot and Scottish with large bills and bulging muscular heads adapted to hard pine cones; the Common (aka Crossbill) with middling bill and muscles sufficient for the softer cones of spruce; and the Two-barred Crossbill with lightest bill and muscles used mainly on the even softer cones of larch.

I have never seen Scottish away from Scottish pines, but beware the fact that the other three irruptive species do regularly snip seed from whatever cones are available at the end of their flights!

Somewhere there must be foresters who know of particular avian uses of introduced conifers such as the Sitka Spruce and Corsican Pine. I have to own up to shunning their dark plantations which have crept so remorselessly over the Scottish moors and English barrens. I have a fondness only for the Douglas Fir in which I found my first Chaffinch nest, 48 years ago.

Mighty Beech and bushy Elder

Let me end with two more deciduous trees and their commonest associated plant. The first is the mighty Beech. I got to know this greyest-trunked tree first in the Lothians where it occurred sparsely in woods but was trained commonly into bright, all-winter hedges often used by roosting finches and buntings.

I experienced it fully in the cathedral tracts of Epping Forest and learnt there what a bird feast the occasional huge fall of its nuts – beechmast – made. Almost every forest bird exploited the carpet of fallen food and the invertebrates under it, with Bramblings and tits always mincing through the nuts and Blackbirds and Redwings digging after the grubs under them and the leaf-mould.

I noticed particularly how Great Tits would track the energetic “turnstoning” of cock Blackbirds and pounce upon their neglected titbits. It was a classic case of intelligent avian opportunism.

The last tree I never ignore is more of a bush. The amazingly vital Elder – “pernicious, more like”, my ace gardening neighbour would say – produces the lushest of all autumn berries, providing another green target for the warbler hunter.

Creeping Ivy

Finally, there is the creeper of all creepers, ivy. Perennial and evergreen, it gives winter shelter to all small birds and its climax growth becomes bush-like.

The resultant reproductive burgeoning of flowers and berries attracts small hosts of insects and these are prey to many birds.

The best bird Ivies that I ever knew were on St Agnes, Scilly. Over my 20 years of visits, their list featured all four British Hippolais Warblers, Marsh Warbler and Red-eyed Vireo. So, every time I look into the lowly ivy, I experience many delicious flash-backs.

Among other native trees of high avian repute are Ash (songpost of many a Mistle Thrush); Aspen; Hazel (adored by small rodents, too); Rowan or Mountain Ash (super for Ring Ouzels); Wild Cherry; Holly (the ultimate safe roost); and Juniper.

Why not select one and find out which birds use it most? Your observations might well merit publication. Please do not take trees for granted. They are some of the nicest beings in the world. They may stand mostly still but they are never boring!