January 1992

Sorting out a fall

Refreshed by a marvellous run of birds in October 1991, Ian Wallace draws on nearly 50 autumns in the field and gives advice on how to search through a mass migration.

After a pretty wearing year at work and a constantly miserable winter, spring and summer on my patch – not one new bird – I was in need of a piece of autumn magic.

Where should I go? Who would make the best companions? Come early October and persistent south-westerlies, was it time for a return to Lyonesse? I had not been there for 13 years.

Somewhat guiltily, I phoned the 0898 numbers every evening and tried to hear the gabbled news (I know the calls cost, but do you have to speak quite so fast?). In spite of the Nashville Warbler and other goodies, I did not scent magic in Cornwall and when a Lapland Bunting accompanied Sky Larks to a local field, I took it to be a sign from the ornithological gods: I turned north-east and headed once again for majestic Flamborough Head and my FOG-gy friends (Flamborough Ornithological Group).

The wind went east on my first day and held there for six more, all full of exciting birds. The high then collapsed but within five days, the squall-bearing backside of a ferocious low, delivered yet another fantastic seawatch. The Head produced a new record passage of Long-tailed Skuas and many soaked observers.

Amazingly, the wind switched back east for the next weekend. Another arrival of Asian birds kept us out from dawn to dusk. My cup of avian refreshment filled to the brim and with my ‘prowess factor’ for 14 days ending on 3.91, I felt a whole lot younger.

No lifer, alas, but two, if not three new races for me in Britain and an old-fashioned bit of DIMW-cheek in a fly-by, call only, Two-barred Crossbill!

Did anything spoil the marvellous mix of place, weather, vector and migrant birds? Well, not really, but I do remain a bit disturbed and certainly puzzled by the behaviour of the twitchers.

As a Desert Warbler was joined by Dusky and Pallas’s Warblers, twitchers came in increasing waves to flood the Head and all but prevented systematic observation. FOG became decidedly schizoid as its members tried to keep up the daily round and also exhibit rarities (trapped and untrapped) to their consumers.

With the nation’s October goodies unusually concentrated along the Yorkshire coast, it was inevitable that many list-builders would come to tick Flamborough’s almost resident rarities. One rather pleasant lad saw three lifers in two hours; the same trio took me 42 years to assemble on my British list. I admired his dash but did he and the others have to be so bereft of ideas on how to find their own birds?

In the whole purple period, only one car crew enquired of me where they might try to find something new. In the same time, I saw nobody enjoy the full length of the invigorating cliff paths. Seemingly, the long gaps between rarity blips were filled only by dense twitcher flock movements, to the amazement of local residents and the delight of local café owners.

The temporal measure of the invasion of Flamborough Head in October 1991 might well have reached 10,000 ‘man waiting for rarity’ hours. Up to 650 lists grew by up to five ticks a day. Many people were visibly and volubly pleased, but just as many did not appear even to smile. So, I found myself asking again how such mass pursuit links to true birdwatching, real skills and never-fading precious memories. No answer came to this question and I left Flamborough Head more than a little depressed by the effect of the telephone on my once-rare hobby.

The year 1991 was also the 25th Ringing Group, long ago awarded the compliment (and high investment level) of ‘constant effort status’ by the BTO Ringing Office. Since I had shared with its members the exploration of the Severn Estuary’s final mud-hole in the mid 1960s, they asked me to attend their Silver Anniversary dinner. Their company – complete with merry ladies – was so convivial that my ornithological blues were reversed in just one evening.

Although the SVRG has trapped, in all their years of dedication, nothing rarer than a Great Reed Warbler, the enthusiasm of the group were undiminished – even under the strain of only three gull rings for £1!

Past members travelled from far and wide for the celebration. Even Nick Riddiford, the Warden of the Fair Isle Bird Observatory and originally a Gloucestershire man, came just to be there. For once, talk was not of rarities, rarity identifications and rarity politics (the last so boring) but of study species, old places and triumphs remembered, new places and successes to come and, above all, fun shared. “Thank the Lord”, I thought, “real birdwatching does live on”.

So, what might the twitchers have done to have made their days at Flamborough Head more achieved and less collected? In the rest of this article, I try to tell you how to get the most out of an autumn fall – by yourself.

The night before Day One

Your best clues to an imminent fall of birds are in the BBC TV weather maps. Look particularly at the weekly farming forecast charts and the daily 1830 and 2130 bulletins, concentrating on those that show both North Sea coasts and the white squiggly lines (isobars). The weather that most often impels large falls of continental birds on to our east and south coasts is characterised thus :

-

A high (anticyclone) over north-west

-

Europe, particularly the Baltic region, with clear skies and light winds provoking mass exodus.

-

An opposing low (depression) along the west or south flank of the high, particularly one with a rain-bearing front over the western North Sea or British coasts.

-

A vector of quickening, easterly, tail winds between the high and the low, producing westerly drift which, when mixed with precipitation, create conditions which inhibit onward passage.

The classic Scandinavian high is not essential to falls. Over the last 20 years, passage-stimulating anticyclones have operated from much more southerly centres, even the Balkans. It seems clear that Asiatic birds can come along more routes then we once thought.

In selecting the area to work next day, the key factor is overnight rain upon it. For an avalanche of birds, ‘total lash’ is crucial.

Fill up the tank, sort out your kit, get some sleep (at 58, silly me finds that difficult, as I still get over-excited). Do not forget the coffee or, better, the soup flask and get to your spot before dawn.

Day One

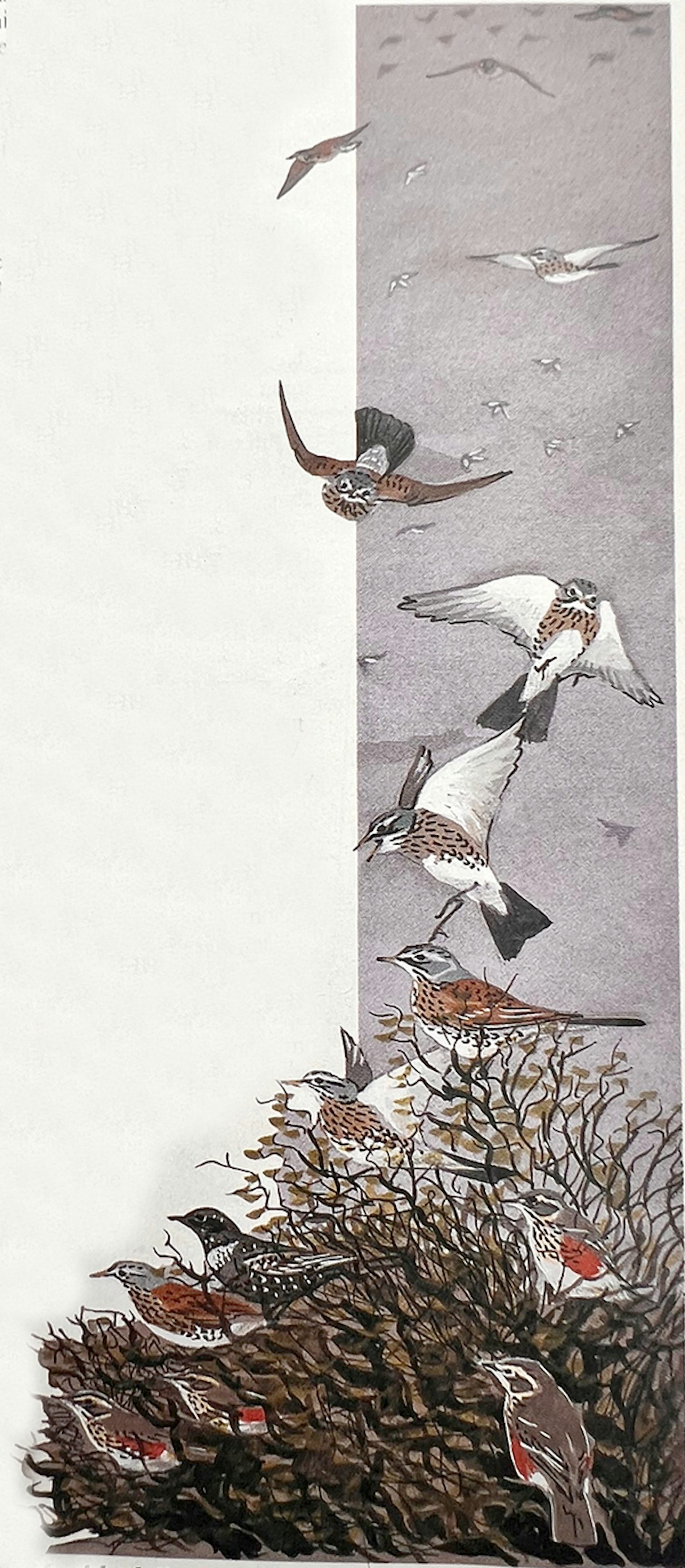

When you arrive at your spot, it is still dark. Have I got you there too early? No. Out you get with your ears flapping. If you hear winter thrushes calling in the wet murk or chattering in the cover, you know immediately you’re in luck.

Try to judge the size of the arrival; listen especially for the harsh-rattling Ring Ouzel, a ‘marker’ for later rarities. Let your adrenalin flow; it could be a long and great day.

It grows light. Now’s the time to start searching the most seaward cover for the more tired birds. They should give you at least one good view before resting. No need for scaring tactics.

Just stroll quietly along, listening, looking. What else is moving upstairs? Small pipits and finches. More diversity of species is indicated. Watch for where the pipits land; make a mental note to search canopies for finches later on.

As the light broadens, chats and large warblers appear. If there are lots of pale Robins, sharpen your eyes even more.

Use your first forays to judge what area of cover or fields the birds are entering. Is it only the shore and first fields? Or deeper inland, even distant woods? If it’s the latter, you have to plan your later search routes so as not to miss birds.

Don’t get too wet which reduces concentration. Better to take cover and enjoy the spectacle of tumbling thrush flocks than risk all day discomfort.

The weather lifts a bit. Go back to the edge of your area; look again for openly perched birds. Leave them until later and they could be feet-deep in bramble.

Once you have a ‘cross-section’ of the fall’s member species, you can judge which cover to search most fully later. Sheep fields for pipits, plough and stubble for larks, woods for thrushes and quiet canopy lees for warblers.

If thrushes are dominant, you will have to search through them first, since they are wilder than most migrants, recuperate quickly and dash headlong on when disturbed. Try slowly rolling them along a hedge or scanning through them from cover.

As you tire of losing thrushes, you should find the smaller birds taking up feeding stations and becoming more active and obvious. Again, it’s slow stalk or wait and see. If they are ‘enflocked’, try to work out their feeding progress through cover before inspecting them closely. Bash straight at them and they’ll probably disperse.

The rain ceases, but fog rolls in. From nowhere, there are crests. You could be in the middle of an avalanche. If you hadn’t thought of finding rarities, you can begin here.

Don’t forget to take breaks and some sustenance. Becoming faint in the tummy is no preparation for a good bird (or another, that looks like one, but isn’t). Go back to where the most obvious concentration of birds are.

Try searching the cover by type. Sallows and Sycamores for flycatchers, crests and small warblers; ground plants and ditches for Acrocephalus warblers and Bluethroats; stubble for ground buntings and so on. Debate all the time where the best food sources are. The birds will have found them already.

Suddenly out pops a really odd bird. Your heart misses a beat but before you see it well, it evaporates. Don’t panic. Stand back and watch. It should return to its chosen spot quickly. If it doesn’t, clear off and try again in half an hour. (Yes, I know some would advise a quick thrash of all nearby cover, but that verges on wilful disturbance – and is against the law).

Patience pays off. There at last, creeping through the bents or flitting in the outer leaf sprays, is ‘the beast’. I leave the rest to your imagination.

In a really rich fall, the rarity may not be the only one of the day. Never ignore their closest companions. Lock them into your memory. You will need to remember the associations to judge the likely gold birds of other falls. Goldcrests on SE winds could mean Firecrest; Goldcrests on NE, could tell of Yellow-browed or even Pallas’s Warbler and so on. You won’t learn such sensitivity on the birdlines.

Once you’ve made your sketch and notes of the rarity, you can move on. By now, raptors could be hunting out the most exhausted birds. Natural selection in action.

Stand hidden in a bird-full hedge for the glint of a Sparrowhawk’s eye only feet away!

If owls come in, look especially for the richly buff Long-eared. The nearest thing to a pedigree Persian in birds, it can be confiding, if you go gently.

The day wears on. If you get tired, use your car as a comfortable hide and let the birds come to you. They often do, flitting between hedges and especially around pools.

Whatever happens, don’t waste any daylight. The hour or so before dusk can be as magical, as that after dawn, as the most tardy migrants make haste to land. Often they pitch into the nearest cover to the sea.

The last task for the first day is to check again on the weather. Remember that the shipping forecasts are as good as the TV weather maps for staying in touch with migration vectors. It helps to learn the sea areas first!

Day Two

The wind has held but the rain has gone. The cloudy sky is quieter. Thrush numbers are way down. Do you depart? No way!

This is the day for the smaller migrants to show better than before, as they continue their recovery of fitness and fat (the fuel necessary to their next flight).

With noisy thrush distraction reduced, you can redouble your searches through the pipit flocks, within the crest mobs and the finch parties. Look particularly carefully at quiet lees (with midges), field sumps, weed patches and wood glades. These provide optimum niches to hungry, small migrants.

Suddenly from a Sycamore, a flycatcher does the tightest of circles and flashes white from its tail base. It can’t be... it is – a Red-breasted Flycatcher!

In mid-afternoon, the clouds break up. The sun shines from an increasingly calm sky. Time to go? Definitely not. Time rather to look for those species that trail in after a fall. A large pipit, a southern falcon perhaps, more finches and buntings.

If there are large-looking Reeds about, a rare bunting may be with them. High up, squeaking Siskins or ‘chit-chit-ing’ Redpolls give other clues of continuing diversity.

If you’ve found a particularly interesting rarity, now’s the time to look at it again. Its appearance may differ in good light, and if it’s little known, you may be able to record a new call or behavioural act. A small piece of world science, no less!

Remember to keep listening to the weather forecasts.

Day three

The high stretches out, the wind stays light and easterly but comes rather more from the south. A beautiful day is born. Even small birds are moving on but if you are free, stay on and keep searching.

What new birds do appear will be fewer but they may have come a long, long, way. So you can enjoy, the full beauty of the scenery and still hope for more surprises.

Suddenly, in a flock of Starlings previously ignored, a paler bird shows. A leucistic Starling? No, you’re in luck again. It has a pale bill and pale legs. Ye Gods, it’s a Rosy Pastor, (Rose-coloured Starling) that has come all the way from Turkey.

And so on..

I have known falls or successive waves of incoming birds last for five or six days. The arrivals are most often strictly coastal but quite frequently they can be detected within 10 miles of the sea. Just occasionally, they spread up to 40 miles inland.

My most recent experience of a crash fall on the east coast that extended in a daily series of thrills, was in October 1990. It started – courtesy of a vicious front across the middle of the North Sea – on the night of the 17/18th and did not end until late on the 27th. Nor was that date the end of the excitements for, back deep in Staffordshire, onward movements were detectable into early November.

To migrant birds, Britain is just an island and so even those of you who can’t get to the coasts or classic autumn islands still have a good chance of seeing dramatic passages. The necessary weather system is, however, not the same.

What you need is a westerly head-wind and lowish cloud, happily often produced by the same depression that pushes away the anticyclone I have described above. When this weather occurs, go out and find a wide horizon and look up. Diurnal migrants at low heights should be on view.

The biggest thrush movements I saw last October and November were not on the coast but over my airport patch and through two snow-covered passes in the border hills!

And what is so good about such movements is their constancy of content and purpose. No Siberian waifs, almost certain never to get home and reproduce, but brave, confident Fieldfares and Redwings, undoubtedly heading for their winter quarters. Another reason for me to cheer up!

Some of the remarks have stuck in my memory and are reproduced for posterity

“I didn’t go to Scilly this year; it’s getting so predictable” (Not when it comes to telling Sora from Spotted Crakes!)

“If vou haven’t tape-lured owlets in Thailand, you haven’t lived. Mind you, it’s a bit much when they try to mount the speaker.” (Well, I think that what’s what I heard, but it is fair on the owlets?)

“I left Scilly on 299; the Nutcracker was 300, the Desert and Dusky get me to 302. I’m off for the Saker!? (Alas with a red ring, it was not going to be 303 ever).

“In due course”(From an observer, informed of a newly trapped Dusky while still intent on seeing the Desert. I liked his single-mindedness

“Where can I get some food? I haven’t eaten for 24 hours” (Man does not survive on lifers alone)

“The county societies are dying. Ours is hopeless” (From someone who clearly knew he should do more than stand in a mob)

“Ah, another Yellow-browed. Thank you, but I do wish I could see a Firecrest. I believe they’re prettier than Pallas’s” (Right on, aesthete!)

“I’m not sure about Reed Warbler; I’m only good at the real rarities” (I know the feeling).