December 1991

Still more on the horizon

[Bold italics means a bird which has since DIMW’s predictions been accepted to British List]

Experienced bird finder Ian Wallace admits that, for him, the hunt for the little brown jobs’ has always been particularly exciting. This month, he concludes his three-part forecast of new birds to come to Britain with a review of Palearctic passerines.

It took me five years of old fashioned, foot-slogging birdwatching to find a rarity, and all of 16 to be in on a new bird for Britain. The latter triumph occurred in astonishing triplicate in September 1954.

On the way to Fair Isle I ‘collected’ the first acceptable Wilson’s Phalarope at Rosyth on the Firth of Forth, and once there ‘shared’ the first-ever Citrine (then Yellow-headed) Wagtail and, best of all, found what, in lengthy retrospect, became the first acceptable Baikal Teal.

Of the three, the wagtail was by far the most enjoyable. Its identification took three whole days, fully testing the collective genius of H.G. Alexander, Ken Williamson, Guy Mountfort and James Ferguson-Lees.

The process left my father, Bill Conn, and me watching with trailing jaws as the experts pooled their knowledge and finally announced, “It’s a first!”.

As the fact that both the wagtail and the teal could well have come from Lake Baikal sank in, we fell into the ornithological trance that the magic of Siberian vagrancy is wont to induce. I have yet to recover from it.

Although I have never again been as lucky as I was in those nine September days of 1954, I still suffer severely from having to earn money in mid-to-late autumn. What a waste of the year’s best bird time!

For most of the 1950s, we felt that new passerines were very much the province of Fair Isle, SE wind and mist, but then a few unprecedented events like the wintering of an American Yellow-rumped (Myrtle) Warbler in Devon, in 1955, forced us to consider other sources than Asia.

Other rich ornithological outposts were discovered and manned through the 1960s. Cape Clear and St Agnes (not yet the quite inaccurate ‘Scillies’!) added the magic vector of ‘south-west, wave depression and ocean liners’.

The tally of rarities and new British birds began its modern climb.

It still continues, sustained by the flood of new observers. As the so-called common migrants seemingly wither away, the uncommon vagrants apparently multiply.

Where do they all come from? Siberia and America remain the most regular areas of origin, but a close look at recent occurrence patterns shows that north-west Africa cum Iberia and south-west Asia must also be considered as sources for new birds.

I do not feel sufficient confidence in my ageing knowledge of Nearctic birds to forecast what next passerine will cross the Atlantic. Alas, I would never have picked Varied Thrush as a contender.

So, forgive me if I concentrate on Old World or, more precisely, Palearctic passerines. My first prophecy of their new arrivals was made in 1979, when I was convinced that vagrants could come all the way from Lake Baikal.

The events of the 1980s clearly indicate that we should look along an even wider fan of approach routes.

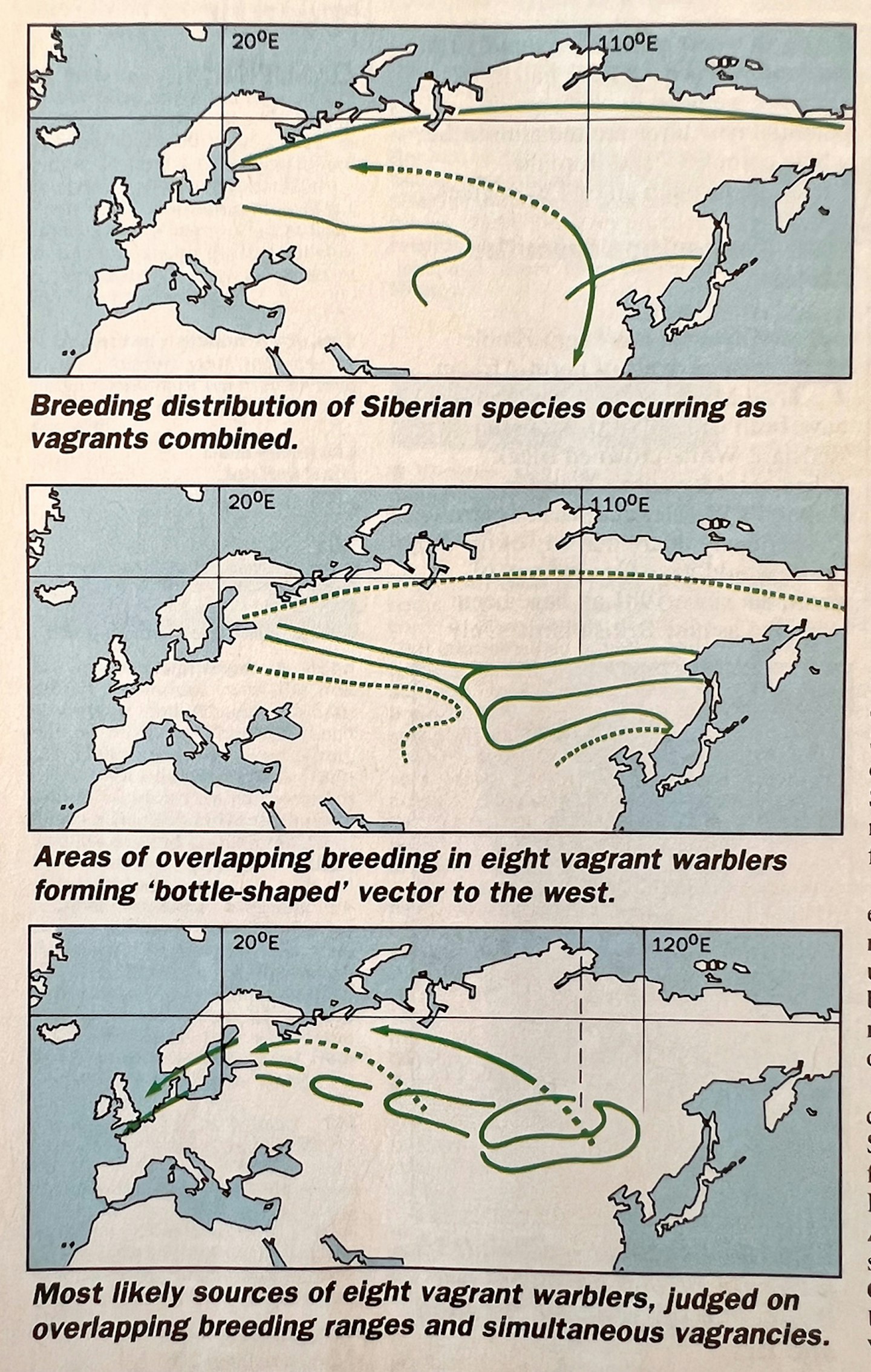

By overlaying breeding ranges, and by comparing the mean arrival dates and latitudes of accepted, related sympatric rarities, I now judge that the potential area of origin for new passerines is much larger than I thought 12 years ago.

The short answer is that, except to the north where passerines rapidly run out (and whence we have had most already), we need to be aware of potential new birds around almost the whole compass – and from the Palearctic through all of 120 degrees.

New passerines from the south

Among the more remarkable recent arrivals of north African and Mediterranean passerines have been Crag Martin, Moussier’s Redstart, White-crowned Black Wheatear, Marmora’s Warbler, Rüppell’s Warbler and Rock Sparrow.

I seriously doubt that any of my old tutors would have forecast any of them, but since 1981 all have been accepted as new British birds. Only the Crag Martin is known to have expanded its breeding range. All the others have simply wandered hundreds of miles – north or north-west – from their nearest normal bounds.

If they can reach our shores, might others follow? A search for the ability to cross water to the north of Africa took me to the detailed texts of BWP and out came the names of two desert larks (Temminck’s Horned – like a desert version of Shore – and Bar-tailed Desert) and one more warbler (Tristam’s).

A survey of winter withdrawals or nomadic behaviour produced Tristam’s Warbler again, another Wheatear (Mourning) and, the last pinch, a starling (Spotless Starling).

If Trumpeter Finch can occur throughout Britain, north to Orkney, then all five have to be considered as potential additions to our targets.

New passerines from the far east

As a term for bird-bearing taiga, ‘Siberia’ can be said to stretch across the Palearctic from the Baltic Sea to the Pacific Ocean.

We have learnt to expect its avian ecotypes, such as Yellow-browed Warbler and Richard’s Pipit as the spice of every autumn.

In the last three decades new Siberian passerines have appeared in the beings of Siberian Rubythroat, Siberian Blue Robin (allowing Sark its best ever bird a mention here),

Daurian Redstart, Eye-browed Thrush, Naumann’s Thrush ([at this time considered] conspecific with Dusky), Two-barred Greenish Warbler (four years in suspense and counting), Brown Shrike, Daurian Starling, Pallas’s Rosefinch, Yellow-browed Bunting and Pallas’s Reed Bunting. At least nine species are involved here.

I believe that about 25 or more Siberian passerines may reach our shores. The most telling single record of recent years is that of the Daurian Starling. Coupled with a sound report of the closely related White-cheeked Starling, the occurrence rolls back the magic carpet of Asian vagrancy ever-further east.

I no longer see Lake Baikal as the eastern end of the Siberian source of new British birds. I now look to the upper regions of the Amur River, beyond which only one mountain range and the Manchurian plain hold off the Pacific!

It may seem an improbable, even daunting vista but observe the other Siberian passerines already known from elsewhere in Europe. These are Black-throated and Siberian Accentors, Pale Thrush (nastily similar to Eye-browed), Gray’s Grasshopper Warbler (as near as Ushant, France), Eastern Crowned Warbler (a century ago on Heligoland), Brown Flycatcher (suspected on Holy Island in the 1940s), Daurian Jackdaw, Long-tailed Rosefinch, Black-faced Bunting (as close as Germany), Meadow Bunting and Chestnut Bunting (four accepted identifications but, due to its high escape risk, still relegated to Category D).

In the wake of the above, there could come another even stranger collection, namely Black-browed Reed Warbler, Chinese and Spotted Bush Warblers (closely related to Cetti’s but in a different genus), Western Crowned and Olivaceous Willow Warblers, Mugimaki, Dark-sided or Siberian and Grey-spotted Flycatchers, Eversmann’s Redstart, Red-tailed Robin (aka Rufous-tailed Robin), Chestnut-eared Bunting and even Black-naped Oriole.

Having seen many of the above two assemblies pouring through south Siberia and north Mongolia in May and June 1980, and rubbing shoulders with many regular vagrants to Britain, I would not rule any member out!

New passerines from the south-east

The British List has long featured and west-central Asia. As long ago as the 1860s and 1880s came White-winged Lark, Isabelline Wheatear and many Rose-coloured Starlings.

Since the 1960s, new vagrants from the arid steppes and hills of southern Asia have included Bimaculated Lark, White-throated Robin, Green Warbler, Isabelline Shrike and Cretzschmar’s Bunting. The bunting creeps into south-east Europe as a breeding species, but the others start at Turkey. Yet the shrike is now annual. We are forced to look for other south-eastern passerines to track them.

Totally clouded by escapes is Red-headed Bunting, but both Olive-tree Warbler and Semi-collared Flycatcher have only Alpine Europe in their way, since they already breed in the Balkans.

Retracing the vector of accepted species back to source produces an even more tantalising list of possible additions. With the mounting astonishments of modern Israeli observations in mind, we may yet have to cope with Small Sky Lark, Long-tailed Pipit, Upcher’s Warbler, Ménétries’ Warbler (claimed for Portugal), Red-tailed Wheatear and Güldenstädt’s Redstart.

Moving on systematically, we also face Black-headed Shrike, Grey headed Bunting and Cinereous Bunting (reported from Corfu last year), Crimson-winged Finch (also in north Africa), Desert Finch and, will o’the wisp, Pale Rock Sparrow.

Within the above are some appalling identification traumas. My recent attempt at a ‘small sky lark’ produced an instant rejection, featuring the capital letters that in my submission I had purposely avoided. This was somewhat brusque review behaviour, in my opinion, but just understandable.

In stubborn return, I would point out again that the phenomenon of south-west Asian irruption is the most neglected subject in all of British migration study. I live in the hope of more claims and less troubled reviewers!

Finally, there are two widely distributed species that hold naggingly onto my mind. I know that Snowfinch went down with the rest of the Hastings Rarities, but is it that much more unlikely than Wallcreeper? I accept that tit irruptions are less strong than they used to be, but I still fancy Azure Tit. It is such a superb little beast and has come as close as eastern France!

To illustrate how the Siberians may come to us, I include three maps which show the remarkable westward expansion of their breeding ranges at higher latitudes and the likely approach route of the individuals that forsake a return to south-east Asia and head further west.

From the last map, you will see that I believe in an arc of Siberian vagrancy of all of 120° degrees from the Greenwich Meridian. Just how many of the 46 passerines mentioned here will fly along it, and be seen when they arrive, is up to the real hunters among us. To be sure, however, there are many more Platinum ticks to come from Palearctic passerines – ‘prowess factor score’: 10 each! Go for them!

Reading up on the potential Palearctic passerines is no easy task. The Heinzel, Fitter and Parslow guide – The Birds of Britain and Europe (with North Africa and the Middle East) – suffices for all North African and most south-western Asian species.

Gaps appear, however, on Siberian birds. The expensive, and systematically slightly odd, Russian field guide by Flint, Boehme, Kostin and Kuznetsov is useful, especially for its maps and plates, but its text is idiosyncratic. To complement it, try King, Woodcock and Dickinson’s Field Guide to the Birds of South-East Asia. This treats all the birds that winter south of north-east Asia.

The best guide to date is Hollom, Porter, Christensen and Willis’s Birds of the Middle East and North Africa. Its text rings with authenticity. Let us hope that one of the new books from the Siberian tour leaders brings the treatment of truly Asian species up to scratch.

After these, there is the long trek to more august (and often dated) tomes, like Ali and Ripley’s Handbook of the Birds of India and Pakistan – strong on wintering species south of central Asia – and similar regional ornithologies.

I adore dipping into these, because they tell so much of local identification history, but I cannot pretend that accessible field characters are their strong point!