November 1991

More potential firsts for Britain

[Bold italics means a bird which has since DIMW’s predictions been accepted to British List]

In his second attempt to forecast which new species might still reach Britain and Ireland, Ian Wallace moves on from seabirds to the non-passerines of the Old World.

Way back in the early 1950s, the race for the first field guide at all worth the name was won by two Richards – Fitter and Richardson – but unfortunately their book suffered from an artificial and cumbersome grouping of birds by size. Most of us continued to pray for a better one.

Three men answered our needs. They were Roger Peterson (progenitor of the genre in America and painter extraordinary), Guy Mountfort (interpreter of human needs and chief author) and Phil Hollom (ornithological geographer and later sound recordist).

With the assistance of the then excellent William Collins Ltd (of the New Naturalist series and many other natural history works), the first classic Field Guide – it deserves its capital letters – went into nearly all our pockets. Field identification was truly advanced in 1954.

By the autumn of 1990, my third copy of “Peterson” (as the Field Guide was often called) was looking pretty weary. Should I buy the fourth edition?

Lo, in the post came an invitation to help the now venerable but still astonishingly active trio write a fifth edition. Thus, for nearly a year the Field Guide has fought with my column in _Bird Watchin_g for the small desk in my bedroom-cum-study!

The Field Guide will be up against much stiffer opposition this time round. At least four more new guides are poised to hit the shelves of bookshops – and our purses or wallets. It will be fascinating to see how they compare.

Will the bird tour leaders share their knowledge at last? In the course of the Field Guide revision, it was necessary to review the records of new European birds. This was by no means easy and I must note that since the decision, speed in the European ornithological bureaucracy is apparently dropping year on year, I have had to err on the side of caution.

Because many non-passerines are relatively scarce, they do not present – individually or as related groups – such obvious patterns of vagrancy as most passerines. The detection of their migratory potential depends much more on their status in their home ranges and particularly the shifts in the latter.

It is clear from recent European News, now so stimulatingly assembled by Tim Sharrock, that really puzzling non-passerine occurrences are fast multiplying. Birds of several orders appear to be pushing north round West Africa and through Iberia; others seem to be pioneering new ranges north-west from south-west Asia to Fenno-Scandia, and yet others are struggling across almost all of Asia to scatter through Western Europe.

Could the first phenomenon be another function of the period of savage Sahel drought, the second a similar response to the desiccation of the Aral-Caspian region, and the third a match to the exploitation by small Siberian passerines of increased polar air circulation?

All three may be, but the truth is that we are almost completely ignorant of why an Eleonora’s Falcon from Madagascar flies not to the Mediterranean but to Lancashire, or what guides a Little Whimbrel from Australasia to south Wales.

Dangerously cosmetic terms like ‘overshooting’ and ‘reversed migration’ are used to paper the cracks in our boggling minds. To the romantic in me, the birds’ achievements remain near-miraculous! Anyway, here goes with my choice of new non-passerines.

[Bold italics means a bird which has since DIMW’s predictions been accepted to The British List]

Herons and Storks

With the Cattle Egret having crossed the Atlantic and successfully colonised the New World, we cannot ignore other herons.Claims of wild Chinese Pond _Herons_ will probably remain hopelessly clouded by its high escape likelihood but we ought to take seriously Africa’s WesternReef Heron. It has fought its way out of the Azores and is now reaching south-west Europe. Little Egret tickers, take care!

Another possibility is Schrenck’s Little Bittern which straggled to central Europe from east Asia. Its vagrancy is “quite extraordinary”, said Birds of the Western Palearctic, but no more so than that of the Daurian Starling.

There are now Iberian claims of Marabou Stork and African Spoonbill. Having seen both full-winged in European zoos, I can understand the reluctance of record committees to give them full credence. In my case, I would bar the Marabou on grounds of ugliness!

[also Great Blue _Heron, Snowy Egret, and soon to be Least Bittern]_

Wildfowl

Having been fair game for hungry humans for centuries, wildfowl corpses have long presented vagrancies hidden in other families. Readers of Bird Watching will already know that currently Marbled Teal from west Mediterranean, Falcated Duck (Teal) from east Asia and even White-headed Ducks from south Iberia are appearing on English waters.

All three have more or less reasonable credentials. For example, the first has flown the Atlantic as far as Madeira and the third has wandered north to the Low Countries. The Falcated only has to track the already accepted Baikal Teal from Siberia.

To these three surface-feeders, we should perhaps add Spectacled Eider which has flown along the chilly north Asian coast as far as Atlantic Norway, and Baer’s Pochard which has yet to reach Europe, but would only have to match the two teals’ efforts to do so. If I remember one of the more delicious tales of the 1970s aright, the eider has been glimpsed in a Lincolnshire snowstorm!

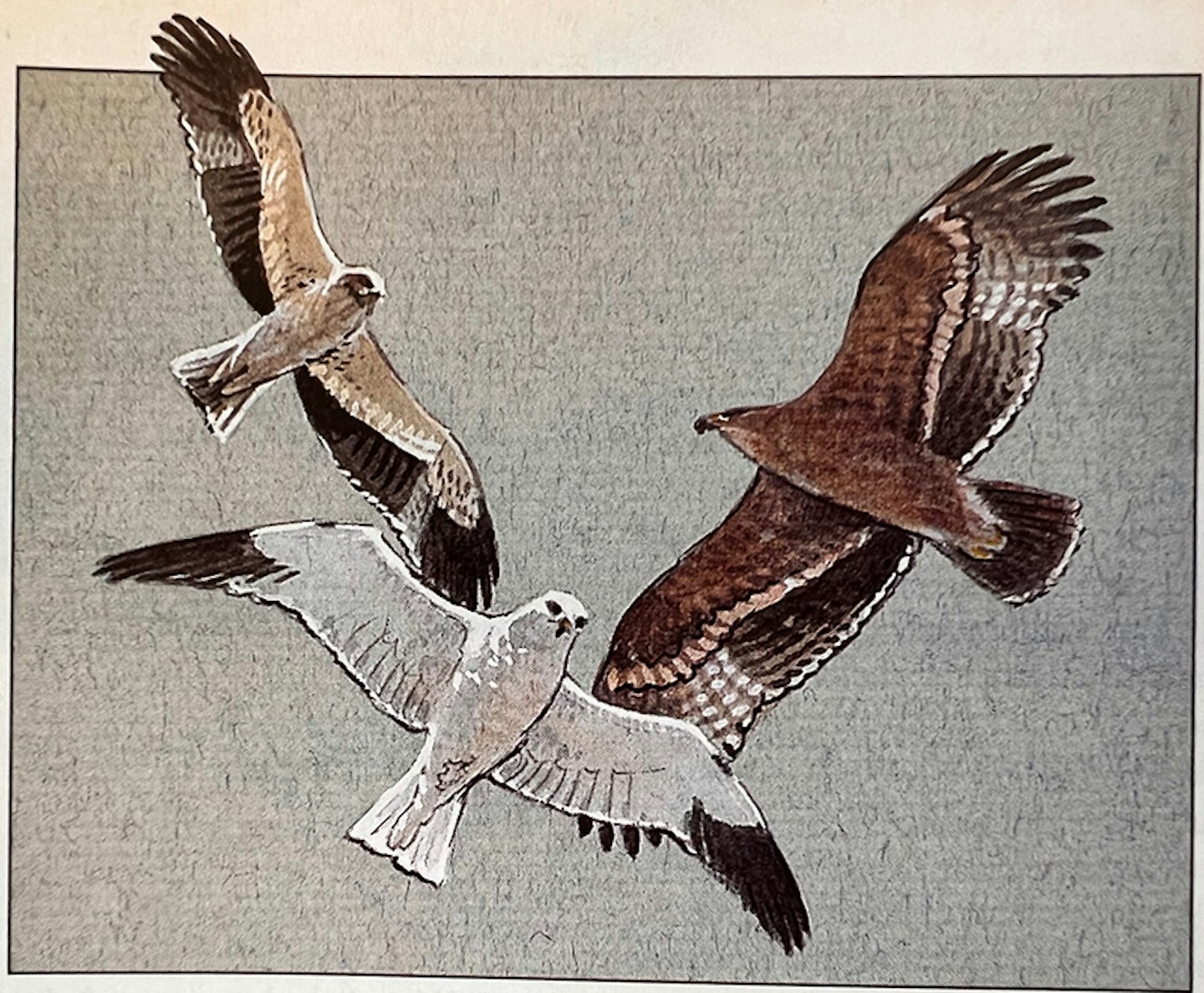

Birds of Prey

Fenno-Scandia, particularly where Swedish eyes are keen, attracts a remarkable number of extra-limital raptors. So although their kind cross the North Sea only rarely, we ought to pay attention to them.

From eastern Europe and southwest Asia have come Long-legged Buzzard, Steppe, Lesser Spotted, Imperial and Short-toed Eagles and Saker Falcon. As a favourite of falconers, the last will always be subject to close scrutiny but happily the others are now very rare in collections. At least three of the eagles and the falcon have been claimed for Britain in the past.

From Iberia, we may yet receive Black-winged Kite. Occasional nomad rather than true migrant, it is doing well in its home range and spreading. More good summers could tempt it north. Again I remember an old (and convincing) report from Essex!

From the same vector, another possibility is Booted Eagle. It is accepted for Belgium, Holland and Sweden and importantly it does frequently cross narrow seas. We really ought not to pour scorn on claims for a bird that breeds within a mere 5 degrees of longitude!

Looking to the east, we should not ignore Pallas’s Fish Eagle, which has come as close as Norway, and two small species which may yet sprint west from Siberia. These are the diminutive Japanese Sparrowhawk and the entrancing Amur (Eastern Red-footed) Falcon.

Neither of the latter would have to do more than Pallas’s Warbler to reach our shores. (Regular readers, for my sins, may just have twigged my belief in the falcon as a British bird in my recent ‘Going for gold and beyond’ article).

The main barrier to new large, soaring raptors will remain the North Sea. Only the Rough-legged Buzzard crosses it with any confidence and it may well be that our best chance of a new ‘broadwing’ will be during the next invasion of that fine northern bird.

Cranes and rails

Although also dogged by escapes, wild Demoiselle Crane and Purple Gallinule (aka Western Swamphen) have occurred tantalisingly close in western Europe. British claims of both have failed in the past but they may be taken more seriously now. One misty, frosty day at Hickling Broad, I waited all day for a huge gallinule, only to find it was Green-backed, not Purple!

Waders

As they make up another order of fantastic wanderers, it is very unlikely that we are near the end of the queue of new British waders.

I doubt if any of my generation would have nominated Greater Sand Plover, Grey-tailed Tattler and Little Whimbrel as future targets but they and other equally astonishing waders have recently flown up to half a world to our lands.

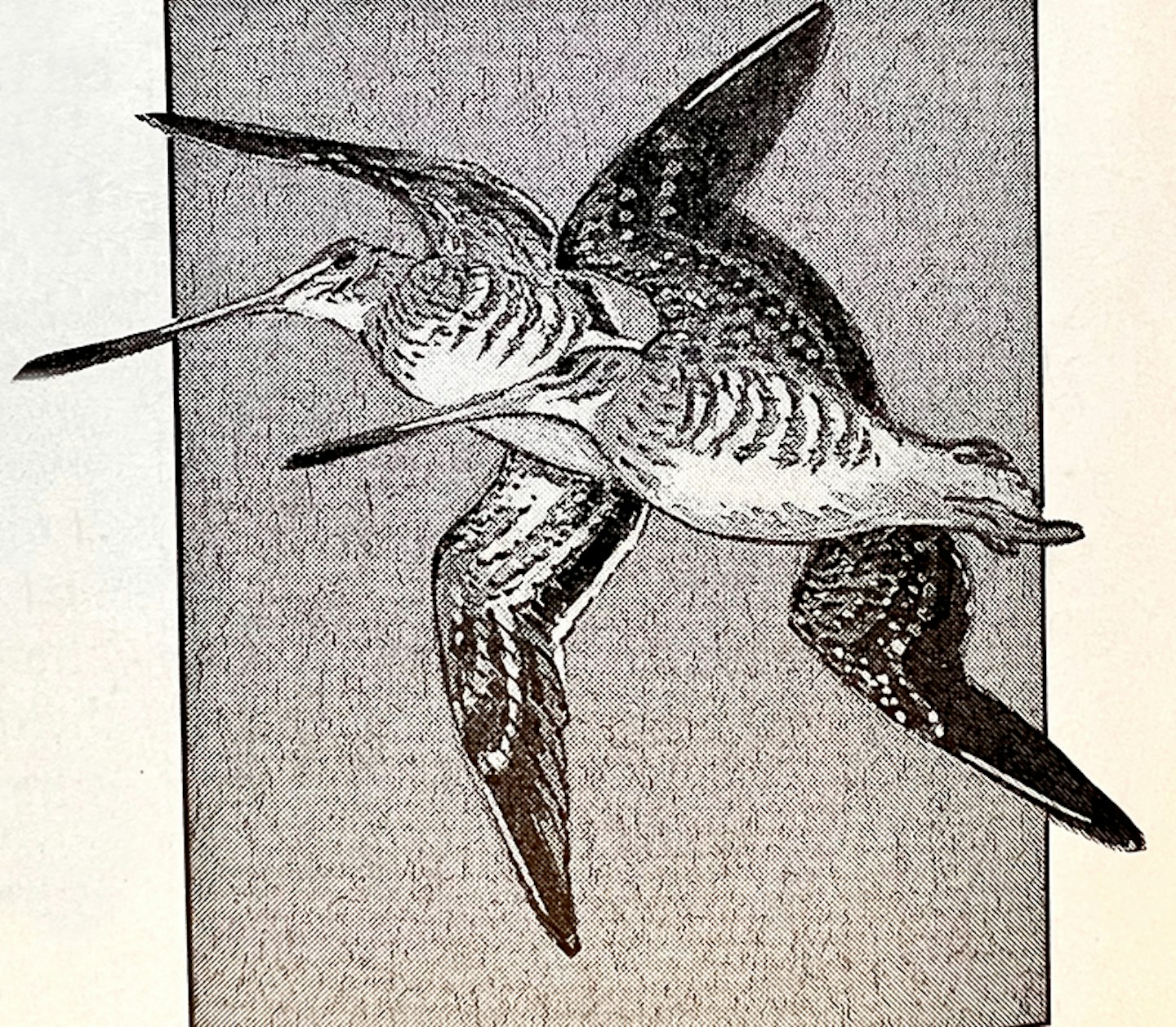

Accordingly, we must face up to the prospect of eight more species that are already known from north Atlantic coasts and west European countries. These are Lesser Sand Plover, Spur-winged Plover, Oriental Plover (no joke; starting possibly from the Gobi desert, it has reached Greenland), Great Knot (now reported from five countries) and Asiatic Dowitcher.

If they can reach across the Palearctic and beyond, so could Pin-tailed Snipe and, just possible, Far Eastern Curlew and Swinhoe’s Snipe. The birdwatcher who does not look closely at every snipe may well pass up on more than Great!

Sandgrouse and pigeons

Not all black-bellied Sandgrouse are Pallas’s; some are Black-bellied, of which

individuals have come as close as Belgium and Germany.

We should be aware that just like Pallas’s Sandgrouse, Eastern Stock Dove radiates out from the Aral-Caspian region. None has been identified further west than central Russia but underecological pressure, it might go a lot further.

Cuckoos, owls and swifts

Only one cuckoo deserves mention and that is Oriental. Two recent claims have not prospered but given its migratory performance in east Asia and definite records west to the south Baltic, there is no logical reason for it to stay away for ever.

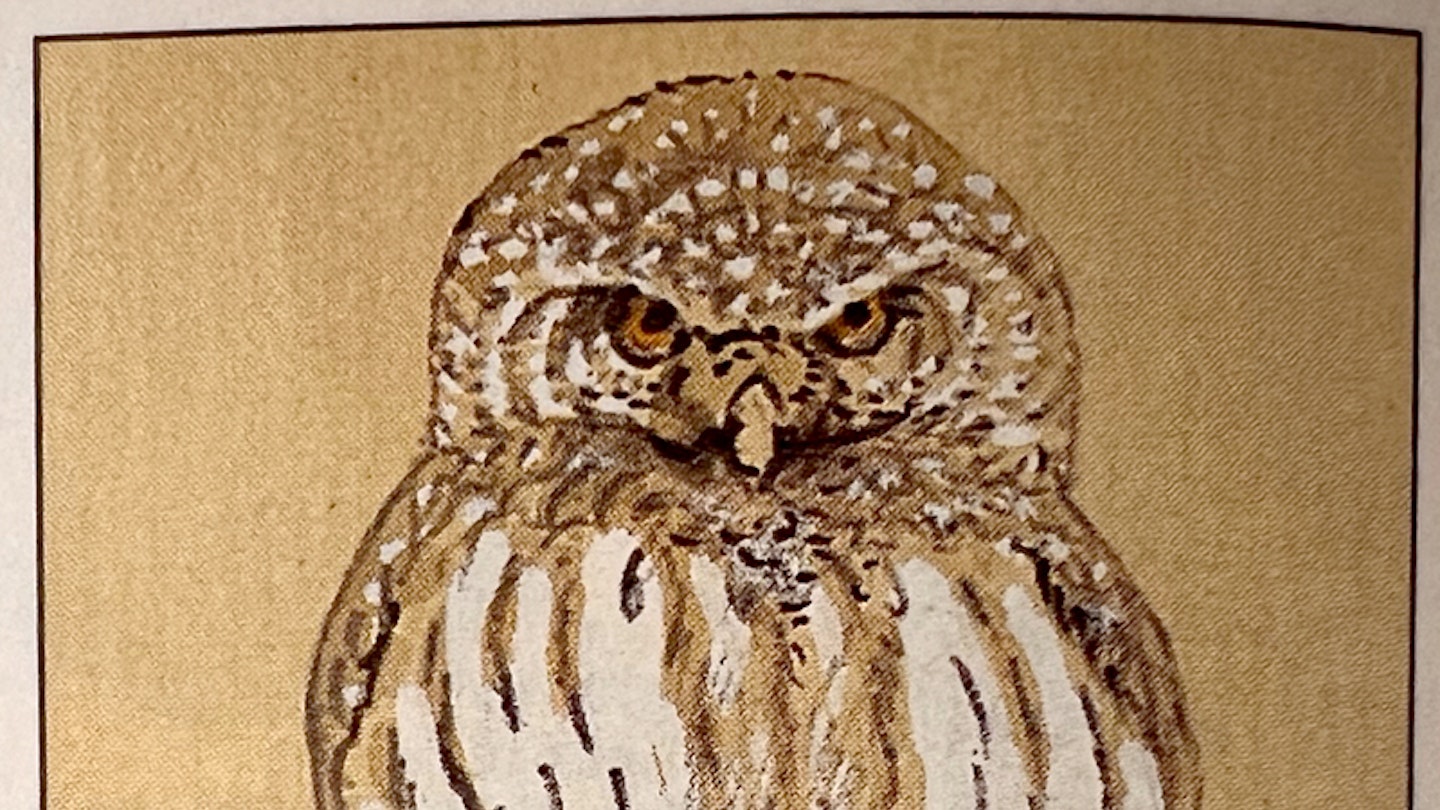

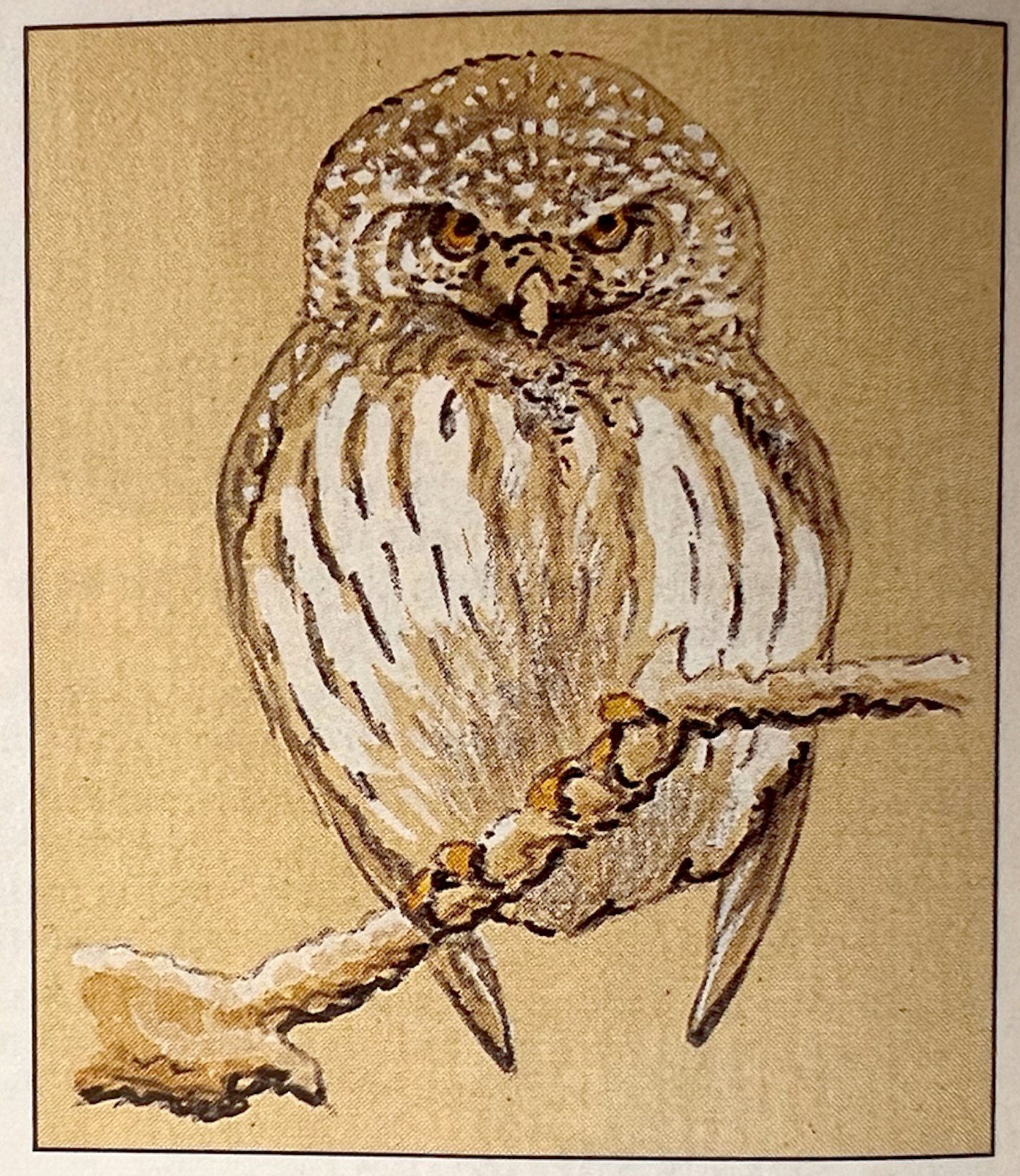

The chance is slim but if Pygmy Owl can skip over narrow seas to Denmark, Germany and Belgium, it might one year hop the English Channel too.

Another real flyer would be Plain Swift of the east Atlantic islands off north-west Africa.

Most northern birds withdraw somewhere in winter and a northbound overshoot in bad Spring weather could deposit it in Ireland.

A much more likely swift is White-rumped Swift. It has successfully colonised Spain and could well track Little along Europe’s western seaboard.

Woodpeckers

We do poorly for these active and engaging continental birds and every time I see ‘Northern’ Great Spotted on the east coast, I ponder on what other woodpeckers might occur.

In spite of all its persistent past rejections, Black breeds only 250 miles east of East Anglia and so has good credentials as a future vagrant. We should be ready for Three-toed, too. It has irrupted south to Denmark.

Rather to my surprise, it has been something of a struggle to put together 36 candidates for new British non-passerines.

Our gun-toting, specimen-collecting forefathers did better (or worse, I should write) with large targets than with small, so there is less in the Palearctic and African cupboards in the forms of non-passerines than there is with the once invisible passerines.

If global warming does change our climate more than so far, we should probably look less to the east and more to the south. We could yet be astonished by more outlandish species from Africa.

My disparagement of Marabou Stork may prove rather foolish. It may well have the last laugh!