September 1991

Going for gold… and beyond

Previous generations of birdwatchers have kept all sorts of bird lists, but today it seems that only the length of his or her British list is used as a measure of an observer’s performance. Ian Wallace muses on a new system of evaluation that really rewards bird hunting and knowledge gathering.

I am an untidy observer. My trysts with birds contain many imprecisions of identity and understanding. Inevitably, the lists that I keep reflect this situation and they stubbornly refuse to line up in neat collections of trophies.

For example, my expedition logs and study patch registers have always had probables scattered among definites. My own British list has dithered between the partial inclusion of Category C (introduced) species and their complete exclusion. They are currently out!

From decade to decade, the list of species seen at favourite places such as Scilly and Flamborough Head has held my keen attention, but I have never suffered from the ‘every bird in its slot’ mania that seems to afflict many birdwatchers.

Bruce Campbell, secretary of the British Trust for Ornithology when I first joined and a post-war force in the broadcasting of birdwatching, kept lots of lists, including a set for the British counties. In his case, the time span was so long – and the details so full – that occasionally the data allowed quite meaningful scientific comment; but, in general, I see little ornithological point in the division of birds by human politic or behavioural boundaries. Fun, presumably; science, hardly.

The late Bernard King was another ornithological elder who surreptitiously kept score, almost to the point of being the birdwatcher’s Wisden.

On a quiet day on St Agnes in the early 1970s, we fell to comparing our own and others’ list lengths. I was a bit disturbed when he suddenly concluded: “Of course, you lost all chance of keeping your lead when in 1968 you took that job in Nigeria”.

“I beg your pardon,” my raised eyebrows replied.

“Oh, yes”, admonished Bernard.

“Being absent from the Hartlepool Ross’s and Ivory Gulls of that winter, never trying for small herons and then nearly three years away – Ron Johns is so far ahead; you’ll never catch him”.

“You mean I held the blue riband in the past?,’ I enquired.

“We’re not absolutely sure,” smiled Bernard, “but it is possible that you were first to every number between 310 to 360. Didn’t you know?”

The truth was that I did not. I had always assumed that James Ferguson-Lees and several other stalwarts were unassailable and well ahead of me. In any case, I had been avoiding milestones after making every effort to make my 300th British bird the 1964 Slimbridge Red-breasted Goose only to find later that I had over-counted by one and was still on miserable 299!

From notes in my third edition copy of Peterson, it is evident that Bernard King must have spurred me. briefly into a fit of ticking and list analysis. Against the date of 23 October 1975, I find the following scores:

“351 wild, 335 self-found, 249 Scilly + 3 escapes, 6 ferals and 10 others eliminated”. Twenty-six years later, I cannot decipher the last class but it feels distinctly stringy. In any case, by 7 October 1979, only the first two scores had by then new totals of 383 and 353, the rest went unrevised.

Sometime in the mid-1980s, I wrote out a new list, but I cannot find it. Clearly, I was either not very concerned with competing with other observers or already conscious that a growing rift with the British Birds Rarities Committee was going to rule me out of play, or both. Alas, on current status, I shall never be a 400 man!

Current species categories

The British Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee (BOURC), places birds on the British and Irish list in five categories as follows:

A Species which have been recorded in an apparently wild state in Britain or Ireland at least once within the last 50 years.

B Species which have been recorded in an apparently wild state in Britain or Ireland at least once, but not within the last 50 years.

C Species which, although introduced by man, have now established regular feral breeding stock which apparently maintains itself without necessary recourse to further introduction.

D Species which have been recorded within the last 50 years and would otherwise appear in category A except that (I) there is a reasonable doubt that they have ever occurred in a wild state, or (2) they have certainly arrived with a combination of ship and human assistance, including provision of food and shelter, or (3) they have only ever been found dead on the tideline; also species which would otherwise appear in category C except that their feral populations may or may not be self-supporting.

E Species which would otherwise appear in category A or B but have only ever been recorded in British or Irish waters between 3 and 200 miles (4.8 and 320 km) from land.

So, for the last 12 years, I have been increasingly spared competitive birding via list comparison. At first, I keenly missed being part of the national reports and still, I get confused by what to do with county-important rarities.

I have to say, however, that the absence of an acceptable score has not removed any of the thrills available from local birdwatching or the occasional full-blooded East Coast hunt. Indeed it has if anything returned such pleasures slowly but surely to their original intrinsic quality, without much immediate peer comment, and little later superior judgement. What remains is the need for personal effort and self-examination just as full as that dictated by my training in the 1940s and 1950s.

With the ghosts of other not faultless observers often around to console me, I have found it possible to survive without any moderating as an observer. I hope that anyone else with similar problems and untidy lists will also take heart.

The obligations that one must twitch, see only what is expected, force your perceptions into others’ moulds and, above all, conform, may seem essential to an acceptable modern birdwatching creed, but once such behaviour becomes inhibitory or burdensome, it will act against the full enjoyment of bird hunting and impede the development of perception.

A clean list – free of ‘string’ (suspect identifications) – may be aseptic but will it keep your dreams alive? A very long list may be creditable, but will it not cost more and more? And where does it get you?

It will be difficult for many, but I believe that we would all be better off if we changed the ‘consumer values’ placed on listing. The acquisition of the magic 400 (or the amazing 250 species in a year) tell mightily of sporting effort, but what do they say of true birdwatching prowess?

I exempt from my comments listing behaviour that has the added benefit of charity sponsorship. This is hunting and gathering into a totally laudable fund-raising end, and, as I read the results of such chases in Bird Watching, I take off my hat to the participants.

In the mid 1950s, I can remember an unofficial ‘Calcutta Cup’ competition between pairs of English and Scottish observers operating within national boundaries. It was managed from the then BB office in Bedford and I played one year, treacherously for England.

We got to 198 species, courtesy of a beat-up old Morris Minor and BB’s grapevine, but Scotland won with 201. Well, they did have Fair Isle while we had hardly discovered Scilly’s position, let alone its cornucopia of rarities.

To return to the point, I am concerned about the scientific and aesthetic narrowness of the merely ticked name. To treat birds as ‘dash and grab’ collectables seems to me to miss most of the point of their evolution and continuing existence as the only dinosaurs around.

The marked tendency for more and more birders to form queues by the discoveries of relatively few skilled hunters is worrying. The most desperate case of ‘tickitus’ that I have ever seen was in 1980 on the Birdquest trailblaze of Siberia and Mongolia. Two members of the party were past 6,000 species.

One still enjoyed most birds along the way; the other lived only for the next lifer and showed quite vicious withdrawal symptoms if it took too long to show. Yet, he only looked at his first Azure Tits for ten seconds!

Last month, I mentioned some ideas that might arrest the trend towards mere list length and rarities. Here is another.

Hand on heart, we all agree that the only fully worthwhile tick is of a new bird that we have found alone or in close company with other hunting observers. We make discovery the sine qua non of full possession.

Hand still on heart, we further accept that a tick resulting from a twitch does not rate as highly as that from a hunt.

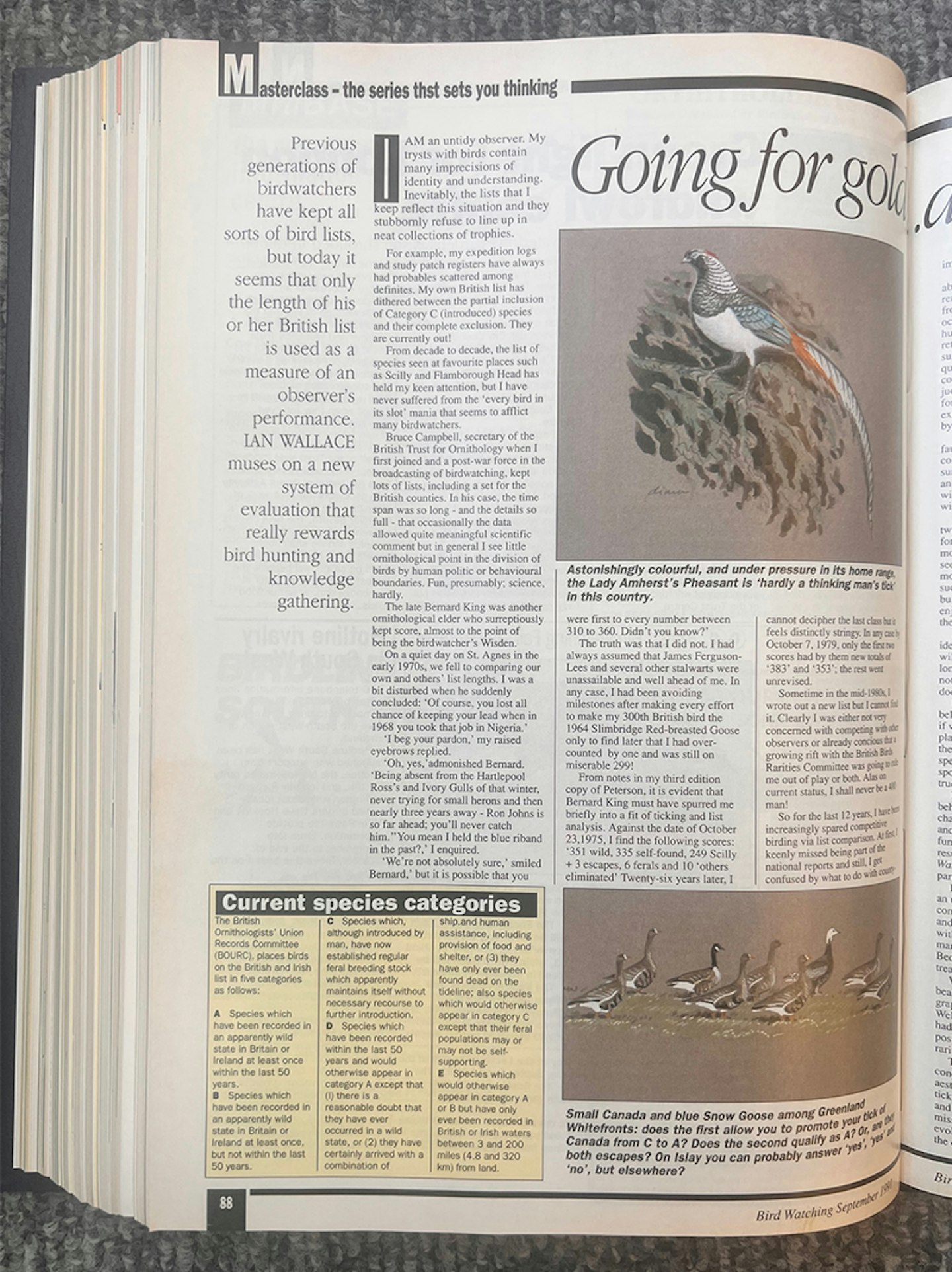

Hand unmoved, we also decide to record Category C species for scientific reasons but not to value them highly in any assessment of personal prowess. Incidentally, this will for example allow me to continue to ignore Lady Amherst’s Pheasant – hardly a thinking man’s tick.

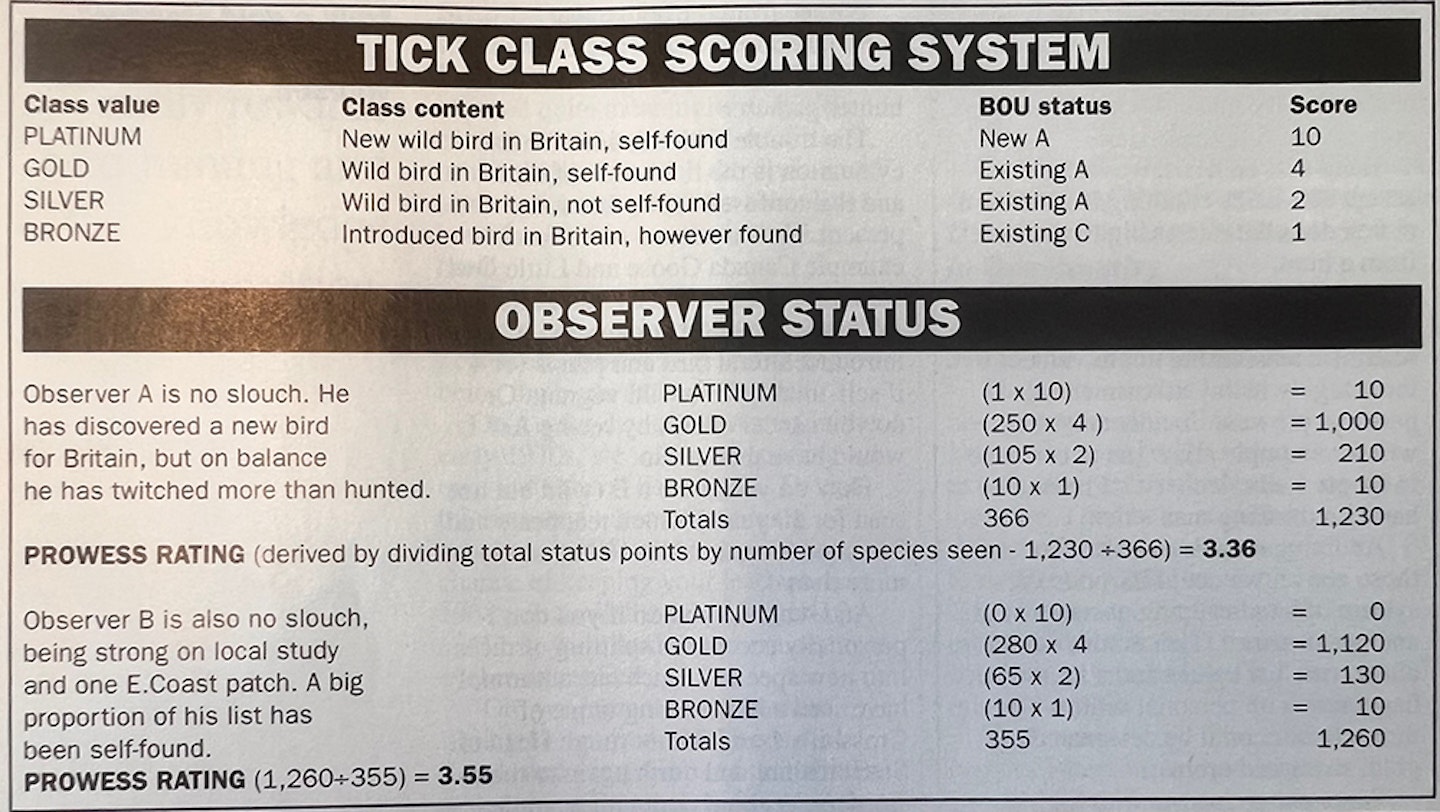

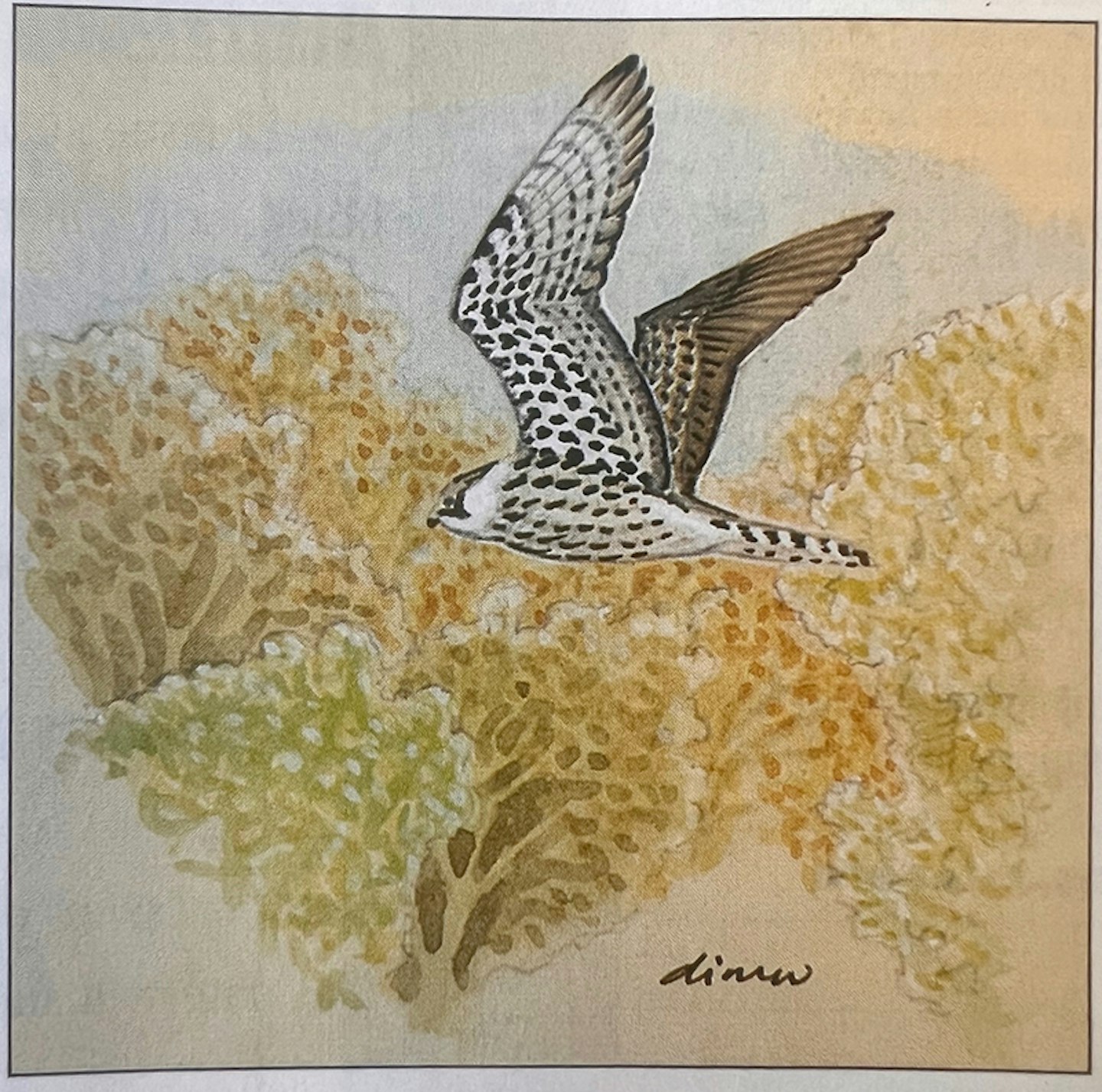

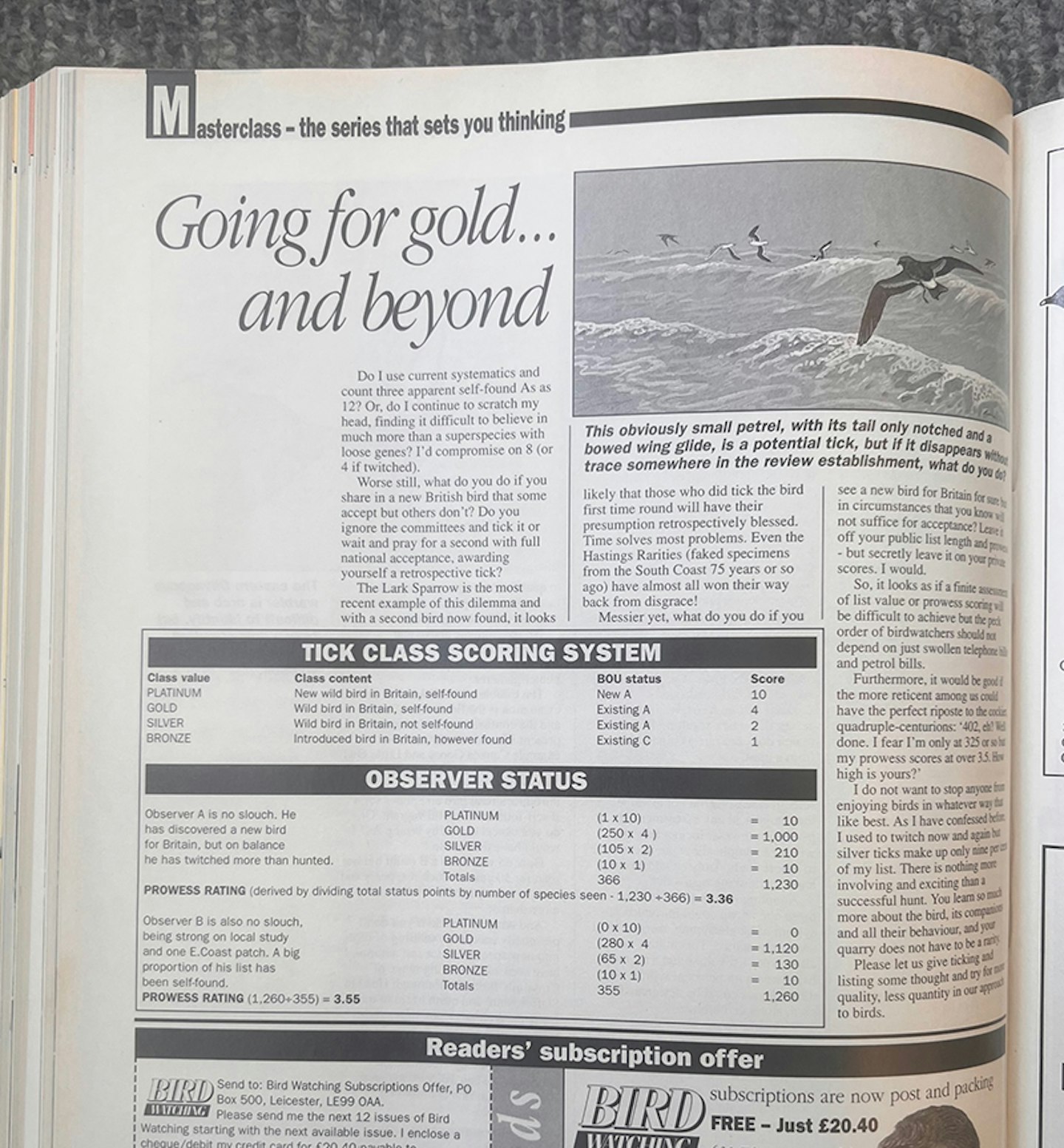

Adopting new tick classes like those above, we could introduce a system of handicapping observer skill and performance. This in turn would allow truer list values and a lot more happiness with personal scores. The three classes could be designated as gold, silver and bronze.

We could go further with list analysis and value by relating the three tick classes to purposeful study, introducing perhaps a platinum class for new British discoveries and even incorporating an element of time handicap.

If we must list, the use of a more diverse currency for the ticks will help to give all observations greater value.

Trained soldiers would more quickly arise from the ranks if more of us went for individual gold and did not invest so heavily in team silver.

I do not expect us to stop telling each other how many species we have seen in Britain, but it would be engaging (and enlightening) to qualify list length with a prowess factor. Here is a partial, fictional example of what might be:

We see from the above that although Observer A leads B by 11 species, B is actually the better hunter/gatherer.

The trouble with this idea for list evaluation is the fickleness of birds and the confused status that some present.

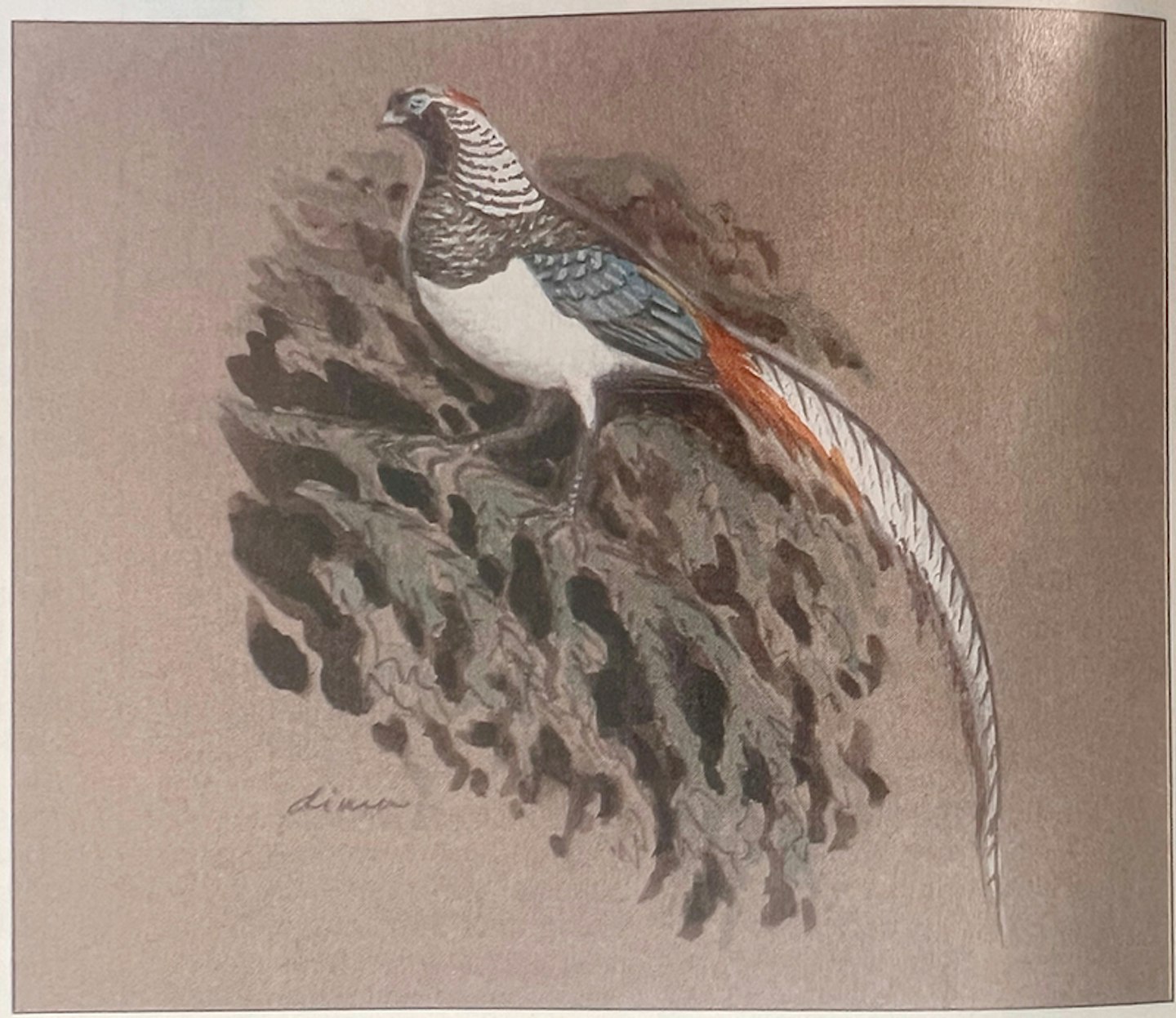

How does one score for example Canada Goose and Little Owl who have been officially categorised AC? Presumably, 1 for an introduced/feral bird and plus 2 (or 4 if self-found) for a wild vagrant. Or, do you cancel out Cs by seeing As? I would have thought so.

How do you score a B (wild but not seen for 50 years) which reappears and becomes A again? Not 10 but surely more than 4.

And what do you do if you don’t personally accept the splitting of races into new species? Since last autumn, I have seen a bewildering range of crossbills from Flamborough Head to Staffordshire and north again to the Borders. Without doubt, they graded all the way down in size from Jumbo cock Parrot’ through middling ‘Scottish’ to titchy-wee juvenile ‘Common.’ Their voices wandered similarly from rich contralto to squeaky treble.

Do I use current systematics and count three apparent self-found As as 12? Or, do I continue to scratch my head, finding it difficult to believe in much more than a superspecies with loose genes? I’d compromise on 8 (or 4 if twitched).

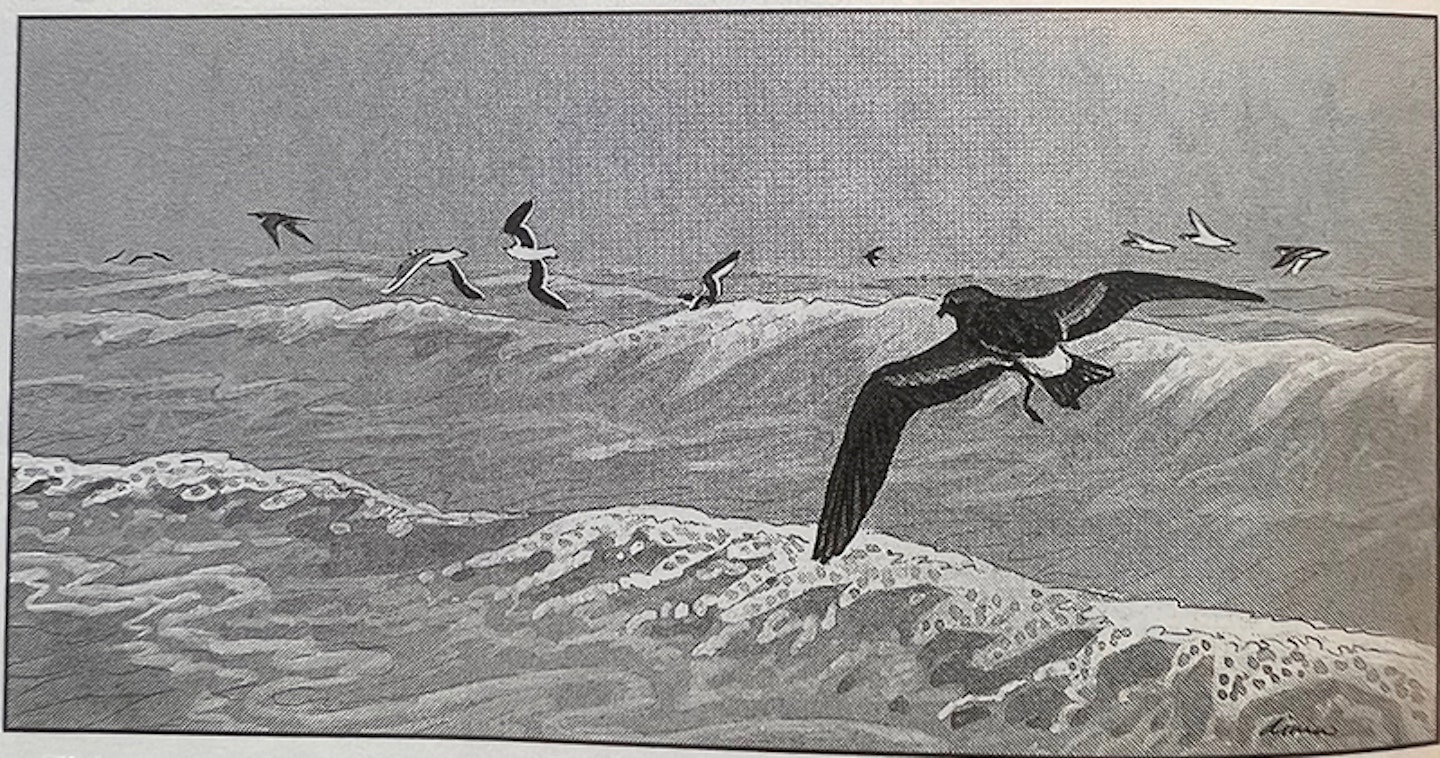

Worse still, what do you do if you share in a new British bird that some accept but others don’t? Do you ignore the committees and tick it or wait and pray for a second with full national acceptance, awarding yourself a retrospective tick?

The Lark Sparrow is the most recent example of this dilemma and with a second bird now found, it looks likely that those who did tick the bird first time round will have their presumption retrospectively blessed.

Time solves most problems. Even the Hastings Rarities (faked specimens from the South Coast 75 years or so ago) have almost all won their way back from disgrace!

Messier yet, what do you do if you see a new bird for Britain, for sure, but in circumstances that you know will not suffice for acceptance? Leave it off your public list length and prowess – but secretly leave it on your private scores. I would.

So, it looks as if a finite assessment of list value or prowess scoring will be difficult to achieve but the pecking order of birdwatchers should not depend on just swollen telephone bills and petrol bills.

Furthermore, it would be good if the more reticent among us could have the perfect riposte to the cockier, quadruple-centurions: “402, eh? Well done. I fear I’m only at 325 or so but my prowess scores at over 3.5. How high is yours?”

I do not want to stop anyone from enjoying birds in whatever way that like best. As I have confessed before, I used to twitch now and again but silver ticks make up only 9% of my list. There is nothing more involving and exciting than a successful hunt. You learn so much more about the bird, its companions and all their behaviour, and your quarry does not have to be a rarity.

Please let us give ticking and listing some thought and try for more quality, less quantity in our approach to birds.