August 1991

Let’s keep twitching in its place

Once upon a time, amateur British birdwatchers followed a multitude of interests, but now competitive birding seems to attract a majority of the young people swarming into the activity. Ian Wallace contrasts the current scene with the richness of yesteryear... and suggests ways of recapturing that diversity.

In recent years, I have been an extremely reluctant lecturer, feeling that my largely self-imposed exile from gadabout birdwatching inhibits my talk, if not my pen. Nevertheless, owing to debts owed to the Cambridge Bird Club and the London Natural History Society for their parts in my ornithological upbringing, I recently agreed to speak to them both.

To judge from their reactions on the nights and later correspondence, my audiences were fairly enlivened; but what fascinated me was their current profiles.

In the mid-1950s, the CBC was led almost exclusively by young, gowned (undergraduate) Turks, intent on dominating three counties. Active, local birdwatchers were few, though similarly energetic. Nowadays, however, the club has a problem holding the interest of young members of the university and getting local effort and leadership from them.

I found this difficult to believe, and I was considerably relieved when after I had reviewed the occurrences of some Siberian vagrants in my lecture, I was led off to the subterranean bar of Emmanuel College and subjected to the most intense ornithological examination ever to envelop me.

Led by the writers of NOT BB, a bevy of young intellects probed for my opinions (or was it weaknesses?) on issues as wide as the state of Birds of The Western Palearctic, twitching, rarity politics and the leadership of British birdwatching.

"I died a total death at the 1983 RSPB members’ conference. Looking up at the serried ranks of largely female tweed, I became almost mesmerised by their incomprehension."

Occasionally flinching behind my pint, I fought my corner as best I could and finally countered by demanding to know just what their contribution to current birdwatching was.

“Migration study in NE China” was the prompt answer and all at once I knew that however shy they may be of club functions, ornithological adventurers continued to thrive at Cambridge. I drove home with at least my own morale considerably restored.

In the late 1950s, the Ornithological Section of the London Natural History Society was organised mainly by mature observers, some of whom had actually begun purposeful amateur birdwatching in the late 1930s. Effectively they bossed a mob of young observers who willingly served before the mast and under their orders.

Attendance at evening meetings was often brimful and the organisation of even concerted, mass migration watches over a 40 mile front was accomplished without difficulty.

I was puzzled, therefore, to re-enter the environment of my mentors and see so few young faces where once there had been so many. As I talked about the current directions of birdwatching, I experienced that particularly deep sinking feeling that attaches to the needless preaching to the long converted.

The average age of my London audience nagged within me, but when, in May, the postman delivered a courtesy copy of the latest London Bird Report, my worry was finally despatched. As I turned its pages and scanned the long list of observers and scribes involved in its writing, I knew that all was well. The LNHS was still harvesting the facts of London’s birds to excellent effect and from all sorts of people.

So, eventually, I knew that birdwatching in and around two cities was after all in good heart and hands, but is it so everywhere? Here are three further tales that portray other birding scenes and practice.

About 1983, I was asked to address the RSPB Members’ Conference at York. Ian Prestt instructed: “You’ll be on after the Duke of Edinburgh. We want you to tell them about real birdwatching. Get out there and enthuse them!”

“I’ll try” I gulped in return.

From my then study of East Riding cereal farmland, I distilled a lecture entitled ‘Rare birdwatching close at home’, illustrated it with habitat photographs and register entries and conceived the thought that I could not only entertain the audience but also convert many of its members into instant BTO surveyors and local report contributors.

The Duke was hardly electric, but I died a total death. Looking up at the serried ranks of largely female tweed, I became almost mesmerised by their incomprehension.

In describing what he wanted to get off his chest

Thank God for Jeffrey Boswall who saved the day by being cheeky about David Attenborough and arguing that in natural history films, the occasional glimpse of animal copulation was slightly essential to understanding how species survive. Heated debate broke out and under its cover, I slunk away.

The morals to be drawn were:

however enthusiastic you may be about your subject, without proper interpretation it may bore others; and sanitised TV dreams are more comfortable and comforting than real life.

From August 1971 to October 1990, the Flamborough Ornithological Group worked within an old-style bird observatory discipline of considerable zeal and turned an icy shoulder towards the profit-making media also known as birdlines.

This attitude won its members the approval of the Yorkshire Naturalists Union, but it incurred the increasing displeasure of the rarity-collecting, fast car-borne twitchers.

On 13 October last year [1990], FOG’s privacy finally began to crumble. The group missed out on the discovery of the Head’s first Radde’s Warbler of the month, but having got the finder’s permission to trap it, they had it in a net, thence bag, in minutes.

Under pressure to return the bird quickly to its hedge, one ringer fumbled its weighing. The Radde’s escaped to become irrevocably lost in a private garden, and as the original finder – a twitcher – had broadcast the news of his find via the telephone hotlines, the hordes were on their way. I arrived at this point to find two stricken friends facing not only a ringing accident but also a ‘PR disaster’.

So it was. With a few honourable exceptions, the twitchers bayed at the purposeful hiding of what they saw as their property and ‘the offence’ was notified to the BTO Ringing Office.

The days of ‘old Flamborough’ were clearly numbered.

"How do we convince young birdwatchers that a £12 sub to the RSPB is better value than the cost of the petrol needed for an overnight dash to Cley or Cornwall?."

For an introspective, even paranoid fortnight, FOG debated what to do and decided finally that it would have to go public with all rarities found in areas of open access. On 27 October, I found the Head’s third Radde’s of the month; my friends trapped it on the first drive and having signalled its presence, we exhibited it to 50 twitchers and a few astonished birdwatchers before releasing it into South Lauding.

The moral – after a fall, God may allow you some recovery of honour, but Bird-collecting Man will have your bird in your place these days.

At the BTO Conference in December 1986, I found myself in conversation with Tony Marr – a power on the South Coast when I was active in London and a thoroughly sane field ornithologist, lately much in Eire.

We came round to the difficulty that young birdwatchers faced in not becoming just twitchers. I said, “I can understand the desire for ticks – I still suffer from it at times – but why don’t they do something else more constructive?”

Tony reflected and replied, “Because we’ve done it all, already. They only have their lists.”

I was shocked by Tony’s remark but it has stuck uncomfortably in my mind.

Indeed, I was keenly reminded of it, in 1989. A young birder wrote to me asking if he could accompany me in the field, since I now lived near him. I readily agreed to show him my Staffordshire study area and explain its remarkable ornithological facets.

The September date was nigh, but he did not show. On the phone, he explained that what he wanted immediately was his first Citrine Wagtail, available in Norfolk. Would I hang around?

I did and he finally showed up in the next rarity-barren winter period. Once again, I died the death or nearly so – 33 years younger than me, he had already amassed a British list of 401 and his identification skills were remarkable.

“If you ever give up twitching and become a ‘trained soldier’, you can be in my platoon,” I implied. “No thanks, I do work the local gravel pits,” he rejoined, “but otherwise I like to be ready for the call.”

No moral – people are entitled to do as they please, but I have to write that it is possible to mix common and rare birds. One does not have to choose between them!

To test other opinions on the current directions of birdwatching, I looked again at the questionnaires completed by Bird Watching’s Local Report correspondents in late 1989. Here are some of their actual comments on major subjects

About twitching

“I believe twitching is an inevitable trend in birding – the predictable manifestation of the competitive motive prevalent in western society – the preoccupation of making everything a sport. The current vogue for bird identification, accurate counting, scientific management of reserves also reflects the ‘intellectual imperative’ that society expects. However, the methods are often based on rather phoney premises. We seem afraid to take a more artistic, emotive, aesthetic view of nature.” Reserve Warden, Lancs.

“As twitching becomes too easy, sterile and crowded, there will be a gradual move towards finding your own birds and consequently migration studies and local patch observations will again take precedence. Member, YNU.

“The one-upmanship which seems to be growing among the more enthusiastic is replacing the old constructive exchange of information. There also seems to be a growing intolerance to beginners and less intense birdwatchers.” Vice Chairman, Welsh Ornithological Society.

“Too many twitchers think they have a God-given right to enter property in pursuit of their quarry – having said that, I’ve seen a lot this year all over the place – their behaviour is getting better and the whip-rounds do help conservation. An Aquatic Warbler on my reserve was seen by 900 people and raised £79 – if everyone had given £1, we could have built a new hide – some deliberately avoided paying!” Reserve Warden.

About establishment activities

“BTO surveys are educational, opening the eyes of observers to aspects they might not otherwise consider, but they are becoming too complicated. To retain mass support, the trust must simplify its aims.”

“The British Birds’ Rarities Committee has become too pedantic in many observers’ eyes – more and more are opting out of contributing – BBRC is too slow to resolve problems and not responsive to requests for changes.” Vice Chairman, Welsh O.S.

“The British Ornithologists’ Union Records Committee is far too slow in deciding whether certain species get on the British List” County Recorders for four English counties.

“There is far too much ringing of tired migrant birds just so a warden or assistant warden can get the bird on their ringing list.” Devon observer.

About conservation

“The RSPB, which is an excellent organisation, suffers from the reputation of involving retired vicars and little old ladies. It would be great to see someone in PR to promote the RSPB in the birder/twitcher’s eye.” Yorkshire observer.

“Despite all the best endeavours of the conservation organisations, habitat – and many common species – continue to decrease. The concentration of effort on a few ‘sellable’ species – on the edge of their range in the British Isles and occupying sub-optimal habitat – is a disgraceful waste of money and manpower.” County Recorder, Wales.

About birdwatchers

“How do we convince young birdwatchers that a £12 sub to the RSPB is better value than the cost of the petrol needed for an overnight dash to Cley or Cornwall?” County Editor, N England.

“Mainly my tripod and telescope! How can one lighten the load? Seriously – I think the birdwatchers of all styles I meet are the friendliest, kindest people it is possible to find! I have no gripes.” Vice president/Editor, English county.

Setting new goals for today’s birdwatcher

Patently, the writers in the Bird Watching survey of local attitudes will not expect me further to interpret their remarks but I do find the level of concern is telling.

In my opinion, we need some new goals in birdwatching, particularly those that will bring young observers in regular touch with broader interests and link their activities to fact-gathering. To achieve this, our new objectives must bait a few sneaky hooks of ornithology with excitement and fun. What could we do to expand purposeful ‘hunting and gathering’?

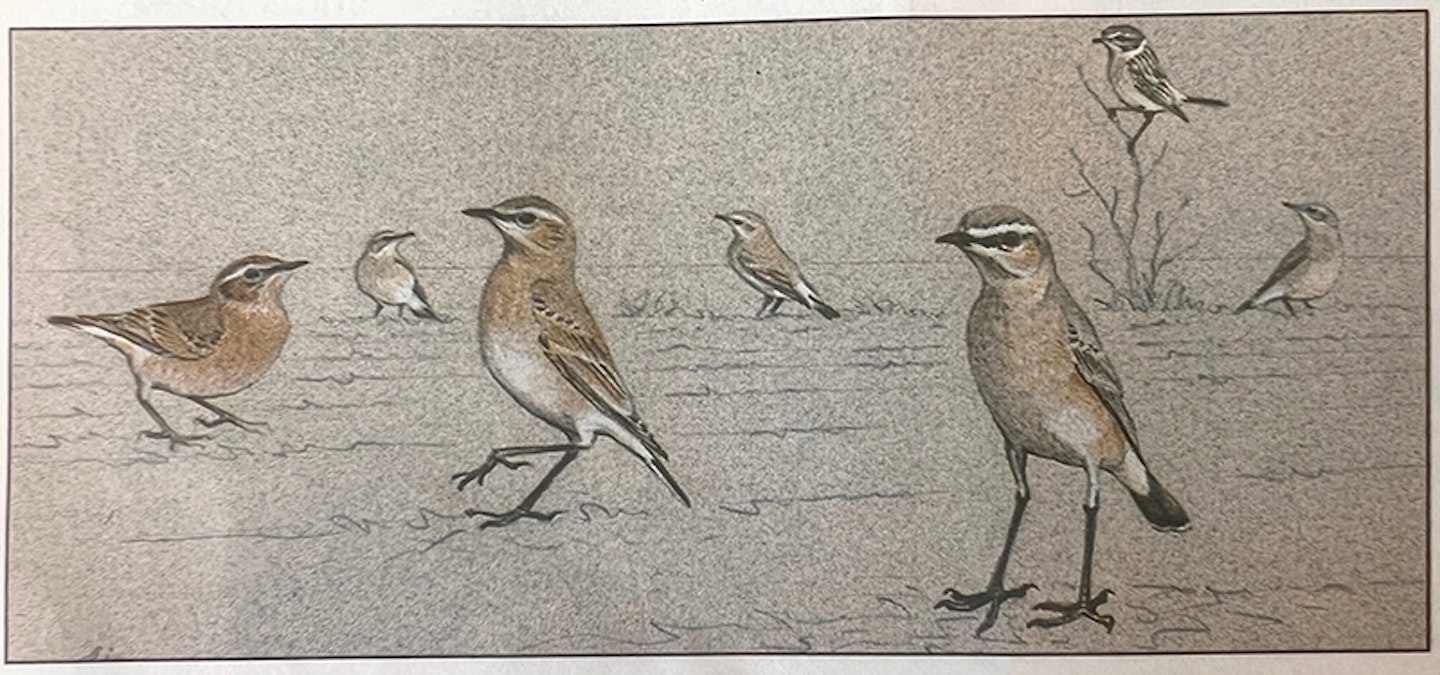

Let’s start with the obvious target – rarities –and let’s say that we want to put them back in their proper context – not the increasingly aseptic annual British Birds list but the main body of migrants in action. How would we do this?

-

We set as our objective the searching of the whole – every inch – of the East Coast on the seven weekends from mid-September to early November.

-

We plan a command structure – perhaps the Ringing and Migration Office of the BTO but better some keen Young Turks (i.e. opinion leaders in the twitching camp, backed by the HQ of one of the national telephone birdlines to ensure fast central intelligence.

-

We appeal for volunteers to cover five mile stretches of coastline each Saturday, allowing their own choice when possible or redirecting effort when there are overlaps. We discipline the searches into a dawn to 10.00 period and get the bird counts phoned in to pre-set numbers and at scheduled times from 10.30 to 12.00.

-

The record receivers log the data, sift out the best birds and collate details of them for the telephone messages. Twitching is allowed from 12.30 onwards but come dawn on Sunday, we start all over again.

A bold exercise and maybe we would have to start with only the English coast but not unworkable. All that is really needed is some inspired leadership and a keen command structure.

Even in a poor autumn, we would establish for the first time, within the total numbers of coastal birds, one overall incidence of uncommon and rare birds within common migrants. That would constitute a real advance in knowledge.

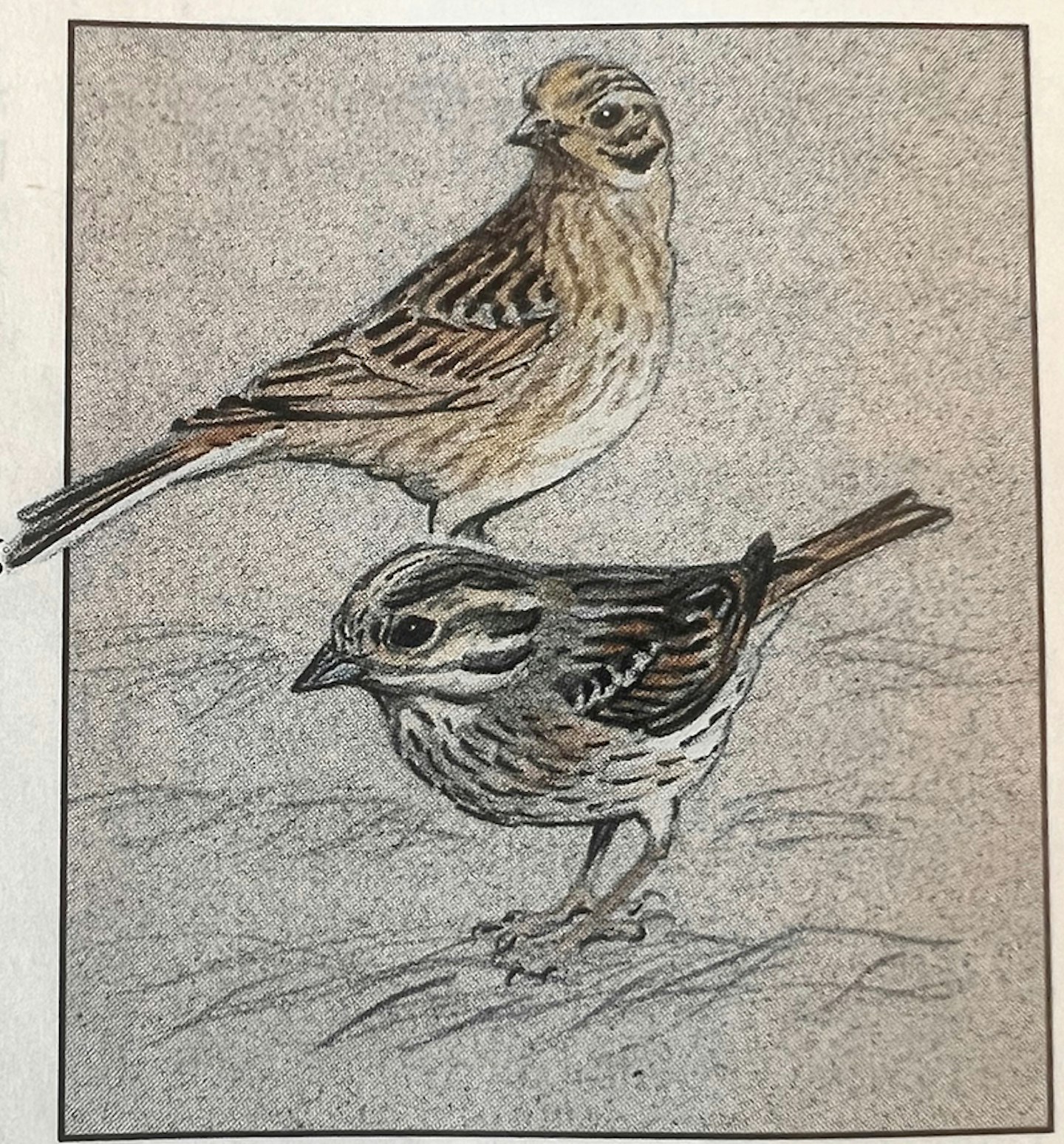

Let’s stay with hunting and gathering – a second target could be the carrier species of rarities, for example Sky Lark, Redwing and Reed Bunting in autumn and winter. So let’s choose the second season and set for November, December, January and February, new tasks in winter status definition.

We would need to structure the campaign intelligently – by habitat class, by height of land, by local climate – and not expect blanket coverage.

-

Within say 200km2 squares, we could ask for every flock of birds visible from roads to be carefully searched and the tallies of oddities again reported by phone, logged, sorted and highlighted.

-

Let’s not forget that 20% of the old White’s Thrushes came from inland localities. The thought of such gems should be enough to gather lots of common bird data.

Common birds? What could we do with them that we don’t already? If, as a BB reviewer and at least two RSPB research officers think, the Common Bird Census is a cameo rather than a full pictureof common bird fortunes, should we not be testing alternatives to it?

So if we get younger observers back from rarities into migrants, can we push them also into common birds? By keeping the chance of diversity in these high, I think that we could.

"We set as our objective the searching of the whole – every inch – of the East Coast on the seven weekends from mid-September to early November."

So I would propose starting off with December and June registers of all species over count lines through mixed countryside.I work 30km but it might be better to set 20km as a more reasonable length for starters.

Once again we would have to discipline the method and evaluate its strengths and weaknesses. It would not be comparable to CBC but, importantly, it could attract far more ‘doers’ than the faltering 300 for the one official scheme.

Organisation would be more difficult than for coastal searches – a task perhaps for a buoyant local society to prove – but one thing I am sure about, the results would be fascinating.I’ve been doing 30km counts for 12 years and not one has failed to deliver surprises in common bird fortunes and uncommon bird occurrences.

Furthermore, the results could be analysed by the observers themselves, reinforcing the drive to data interpretation and providing the linear incidences of birds – birds/km, not pairs/km2 – in both woods and fields. Importantly, line counting is a relatively simple task – 2km in a hour is possible – and its fascination builds each time round.

“Are we getting our figures right?” is an important question in broad-front conservation. It is time that we gave the trends in observation, more inspection. In particular, we need a determined attempt now to scale the effect of observer effort on avian status. The latest digest of vagrant records is woefully lacking in it and the BBRC ignores it every year without fail.

As common migrants appear to fade away – where are the day-long visible passages of the 1960s and before? – the numbers of vagrants seemingly build.

Yet no-one since Tim Sharrock in 1976 has made any real attempt to balance bird records against observer numbers. It simply is not good enough – a clear chance for young and computer-literate minds to do something useful before we lose track of the trend, forever.

There must be others with ideas on how birdwatching in the round can continue. It would be good to hear from them. Writing this article as a depressingly cold spring slips into a windy, watery summer, I find it difficult not to feel some pessimism about common birds which appear to be unusually thin on the ground and have reared very few young so far.

It would cheer me up no end to see some new amateur initiatives and many more young contributors to them. Birdwatching is the perfect antidote to boredom but there are few journeys more fruitless than a twitch-less twitch. Let us get our act together again, and advance field ornithology once more!