July 1991

Misguided and misbehaving

All over the world, Man presses ever harder upon Nature. Ian Wallace takes two sideways looks at conservation issues, discussing the ignorance of farmers and other land-users and the selfishness of birdwatchers in Britain.

When I was a lad, catapults and egg collections were parts of many boys’ lives. Neither machine nor act was against the law. Wildlife was so (relatively) abundant that while the occasional more-sensitive adult locked a frowning eye at me, many others owned up to their own earlier sports and even encouraged their continuance. I can remember two elders with drawers and drawers of eggs, from sky-blue Dunnock to red-brown-dappled Peregrine. Indeed, I became so enthralled by their tales of derring-do that I started an egg collection of my own, learning much about breeding behaviour in the process.

Happily (we would all say now), I lacked the necessary patience and concentration for time-efficient nest-finding and, once I had also learnt how vicious a catapulted pebble could be – courtesy of the reproach in a dying Song Thrush’s eye and a guilt complex that lasted for years – I put away any aggression towards birds. When, in Ulster in the winter of 1957, Joe Cunningham, a friend of my Cambridge years, put a 12-bore in my hand and led me into a Woodcock wood, I could not even hit a thrown can. My hunting instincts had subliminated into the chase for identities, not trophies.

Thousands of my generation must have gone through a similar conversion on the road to the modern attitudes to bird protection which are now backed by law, thanks to the RSPB and NCC in particular. These days I continue to flinch from individual acts of cruelty and disturbance. Their scale may be small, but their effects are sharply comprehensible. For the general wanton accidents in support of so-called civilisation, such as oil spills in the Gulf and wholesale habitat impoverishment, I feel fear for all children and a growing bewilderment about how we shall reverse the increasing dilapidation of our planet.

Even in the tiny canvasses of my last two study areas, the trend has been consistently towards less diversity of habitat and consequently fewer species of animals. What can be done?

Now and again, the ornithological media discuss local trespass or pressure upon birds, but I get the impression that while some would recognise a recent bad patch, most feel that current behaviour has improved. To my eyes, the reality of the issues is very different. However reprehensible each individual act, the disturbance of birds by birdwatchers is minuscule. Truly there is a nasty grey area between legitimate close approach, as in ringing, and illegitimate pressure, as in tired vagrant hunting, but no body, last of all the RSPB, wants to accept the role of policing acts that hardly touch the avian mass.

Thus, the leading conservators fall back on the Birdwatchers’ Code as it usually does, good sense will prevail, and press on with their research, reserve management and vulnerable species protection. With scarce resources, they must concentrate their efforts.

Unfortunately, this state of affairs leaves most birds unprotected on all flanks. This may seem a mite pessimistic, but unless my eyes deceive me, the biggest threat facing birds is the still enormous ignorance of their fairly simple needs. Who addresses it?

Let me look at this question in two situations – the general care of the countryside and the close hunting or investigation of birds themselves – and see if we can come to an answer.

Ignorant disturbance

Despite their best efforts, Attenborough, Soper and Boswell are failing to make responsible natural historians of us all. Armchair dreams, alias TV programmes, are entertaining and informative but not truly educative. There is still a woeful lack of lasting useful knowledge about wildlife.

The farmers whose land I have trod in recent years have remarkably confused attitudes to conservation and birds in spite of lifetimes spent on the careful cropping of edible plants and animals. However skilled they are in understanding the needs of the latter (and those of Pheasants), their knowledge of wildlife and its requirements is oddly incomplete; indeed dangerously so.

Because I have chosen to study the unbuffered impact of modern agriculture upon the countryside and is wild inhabitants, I make it a rule not to preach at land owners or users. The occasional suggestion, or answer to the rare question that they put, is all that I allow as I greet the people who give me access to their fields and woods. Accordingly, I have to grin and bear it when misdirected efforts at conservation actually subtract yet more diversity from my local habitats.

Nowhere are these more apparent than in the few last wet places left among the carpets of monoculture. Both in the East Riding and East Staffordshire, I have had farmers adopt ducks and try to do something to hold more of them on their land. In the first case, an old, open sand-pit with reeds at one end and well-broken edges was savaged by a JCB, ending up as a steep-sided trench with ornamental tree screen.

The effect of this ‘improvement’ was catastrophic for birds: a small isolated colony of Reed Warblers lost their niche; the common rails could no longer find enough food and went elsewhere; and apart from some loafing drake Mallard in summer, ducks departed, too. The local Kingfisher lost his perches and never came again.

In the second case, a shallow pond-cum-small marsh had proved itself a magic place. At least seven duck species, especially Teal and Wigeon, fed there; five waders, particularly Snipe, visited it; night migrants recuperated around it, and once, Waxwings came to its few Birches.

Again the power of a JCB was employed to ‘improve’ the place. The plan was fine to insure permanent water for ducks likely to be disturbed by a nearby golf course development.

More central depth was required, but alas, this was achieved only by the erection of spoil rampants on three sides. These in turn covered the sedgy side beloved of Snipe, broke into the open horizon needed by Wigeon, then blotted it out except to the windy south-west and, by changing the water level, altered to the flora to the detriment of all the insect- and seed-eating birds.

The outcome was disastrous. Duck still came at night but only at the cost of corn specially put down. During the day, they scared easily and soon shunned the place, with the Wigeon presence collapsing to one small party. On one day in a whole winter. Snipe evaporated and even the hedgerows held fewer passerines. Yet, I was supposed to applaud when the farmer announced with pride the coming of a pair of Canada Geese!

Thus two well-intentioned (and costly) acts produced precisely the opposite effect than that desired.

Waterbirds were not tended but seriously disturbed. As both land changes could be considered wilful were they breaches of conservation law? And if so, who can do something to restore the losses? Better still, how could they have been prevented?

Recently, I put these questions to Bob Scott, the second longest-serving officer of the RSPB, and he confirmed that in an ideal situation, it was the role of the FWAGs (Farming and Wildlife Advisory Groups) to provide the education and practical advice necessary for more sensitive habitat management within farmland.

The snag is that FWAGs are not proactive in what they do. No farmer in my last two patches has volunteered knowledge of them! The media, even Linda Snell in the Archers, do much to sell conservation, but in my experience, the cumulative impact of such preaching upon those people who most shape the countryside has been negligible.

Something must be done to increase land-user education or, as the fears of Bird Watching correspondents summarised in my Review of the 1980s clearly demonstrated, the diversity of our mainstay avifauna will continue to fall as the machine-cleared character of farmland increases.

“Something is being done”, I hear you think, “there’s the new policy of set-aside. Through it, farmers are paid (a little) to allow land to go back to nature”. In the last three years, I have counted birds in three set-aside patches, one in Flamborough Head and two in East Staffordshire. I have to say that, judged by the visible regrowth of diverse plants (= more food for insects and birds), the three areas are slow to prosper.

"With experience, it is possible to know when birds need to be left alone to breed or feed. The tell-tale signs are extreme nervousness – often translated into panicky distraction displays – and obvious fatigue – demonstrated by drooping wings, slow gait and dull eyes. On no account, pursue birds in these states. Back off."

No reborn meadows are apparent because, in all three cases, the land has been left as last dressed and harvested.

Little wonder then that the invasive flora is struggling with the “thatch” of decaying stubble, the ‘burn’ of persistent chemicals, the unevenness of tractor tracks and the dominance of unharvested animal feed plants. So far I cannot, from a disciplined before-and-after count register, score the areas more than 55% as bird-sustaining as they were in their normal cropping cycle.

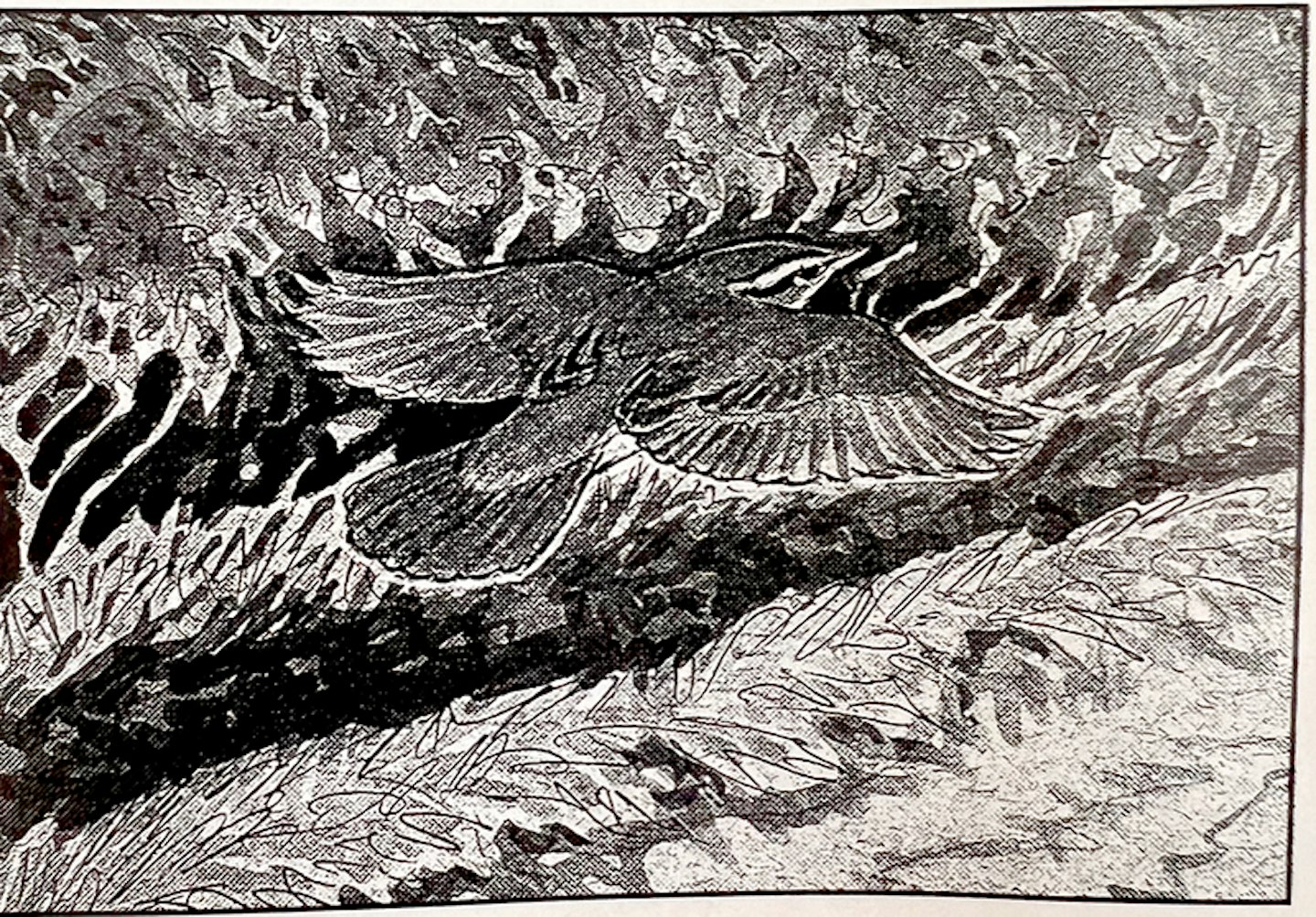

There are hopeful signs – a marvellous flush of Scarlet Pimpernels at Flamborough, a new winter sanctuary for Reed Buntings near my current home – but once again the overwhelming impression is of kindly but intrinsically ignorant efforts at conservation

These are large issues that need more attention than they currently receive. I should like to see the RSPB take on the NFU as a partner in order to test a diverse habitat regime for every farmland type. Given a joint policy, the pro-active dissemination of practical conservation hints to all farmers could take real root.

Selfish, knowing disturbance

Set against the misdeeds of ignorance discussed above, the disturbance of common birds by individual birdwatchers is of only marginal consequence. Even so, where human (acquisitive) imperatives threaten our cool, we all have to beware breaching the Birdwatchers’ Code.

We must also recognise that the potential to disturb birds wilfully exists in all modes of birding. It is not restricted to twitching.

In fact,it is hardly possible to see birds well without interrupting their behaviour to an extent. Thus, we all face the duty to make repeated judgements on what degree of disturbance is allowable and what is not. No law or code can help us with specific decisions.

Of course, there can be fully acceptable scientific reasons for the closest approach and even capture in such situations. How else did RSPB researchers find out that Nightjars do best on a patch of cleared ground under a small conifer, or BTO-led ringers prove the origins of migrant waders in the Wash, or NCC experts determine the stresses on estuarine species of ice-locked mud? For effective long-term conservation, we need to know our birds and their biologies as fully as possible.

This stated, I sense that more and more of us suffer from mounting, nagging doubts over some of the more perpetually motive acts in field ornithology and birdwatching. ‘Catch as catch can’ ringing, ‘all-day same-vagrant’ thrashing, unruly twitches and habitat scarring by pressure of too many feet have all attracted particular criticism in the past and will do so again.

Asked about their policy on such issues, the RSPB is (quite rightly) somewhat shy. Pressed, it quotes again the Birdwatchers’ Code and points to its own exemplary corporate behaviour and education programmes. However fiercely they hunt for egg collectors, the society’s officers do not want to have to supervise birdwatchers as well.

So, we are on trust to behave, using our senses (and consciences) to make a lifetime series of decisions on what is right or not right in our close approach to birds.

With experience, it is possible to know when birds need to be left alone to breed or feed. The tell-tale signs are respectively extreme nervousness – often translated into panicky distraction displays – and obvious fatigue – demonstrated by drooping wings, slow gait and dull eyes. On no account pursue birds in these states. Back off!

To get experience in the judgement of avian fitness, you may practise on common species. There are still enough of them for you to make a few mistakes or cause accidental disturbances. Just learn from them as quickly as possible.

With any vulnerable individual or flock, you should steel yourself not to press upon them. This means ‘hanging back’ rather than ‘charging forward’, not easy when a tick is imminent, I admit. So, remember my earlier advice on ‘waiting and seeing’. Close views of a bird that has come to you are truly the most joyful.

Your over-riding principle should be to avoid any act that more than briefly interrupts a bird’s peace. This will mean for example no stone throwing to cause flocks to fly, no bush-bashing to panic migrants into the open, no nest study without a hide, no loud noises ever and always a quick retreat the moment that you complete your observation.

In place of the extreme acts just noted, you should take up the challenges of a careful stalk, a gentle push through cover (into wind) or quiet ‘pishing’ to make the bird investigate you, a patient watch through binoculars from nearest cover or car and quietness. All of these take time to perfect and employ, but I assure you that you and the bird will benefit from your increased fieldcraft.

My own rules of engagement vary by season. I am most conscious that my approach may become trespass upon birds and their niches in:

-

their reproductive cycles,

-

their immediate recuperative cycles,

-

their immediate recuperative periods after migration and

-

their struggles with hard weather, particularly glacification.

Finally, you may face the need to counsel others to be less eager in their pursuit of birds. This will not make you popular but when ‘red mist’ descends and birdwatching sense evaporates, someone has to speak out.

Faced as I have been over the years with charging mobs, obsessive attempts to trap rarities and trespass into private land (and hence safe birds), I have found that quiet but clearly annunciated appeals to reason works best.

Only once have I made the mistake of telling the jam-packed audience in Slimbridge’s Holden Tower that a Red-breasted Goose was in fact behind and not in front of the hide. Had we been in a boat, it would have capsized instantly!

P.S. Pishing? Making quiet sibilant or squeaking sounds with your lips, and so getting small passerines intruiged enough to inspect you from feet or inches!

.