June 1991

Introductions and escapes

This month, Ian Wallace continues his discussion of murky birds. In a survey of introduced and escaped species, he looks at what are known as Category C members of the British List.

Note that up to date population estimates are included within the text in square brackets

When the last volume of the old Handbook appeared in 1941, the official British list included only five species that were neither true residents and regular visitors nor active migrants and vagrants.

The group of impositions consisted of three gamebird: Pheasant, Capercaillie and Red-legged Partridge, and two other non-passerines: Canada Goose and Little Owl. With hindsight, it should also have contained another non-passerine: Egyptian Goose, but clearly the august authors of the Handbook held it in little favour!

The gamebirds and the geese stemmed from deliberate introductions by the landed, shooting gentry, with the former destined for sport (and the pot) and the latter designed for estate decoration. The owl came from the desire to give our lowlands a small nocturnal raptor.

Of the six species, the longest established by far is the Pheasant. Though the popular myth of Roman importation has never been proven, a “long-tailed partridge” was certainly present in Essex by 1059. A striking and eminently edible gamebird, it had become widespread by the 16th Century.

The original Pheasants were of the western race colchicus from the Transcaucasian region, but from 1785, other forms, particularly the eastern Chinese torquatus, were put down.

As the BOU rightly noted in 1970, the population is now “completely mongrel”. Courtesy of a remarkably community of country people, covert management, mass rearing and sustained keepering, about 8,000,000 [Now, the in the 2020s, closer to 40,000,000!] Pheasants fledge to face the annual Autumn barrage.

However mixed their blood, cock Pheasants remain truly beautiful birds and actually it is quite fun to guess which genes are present in them. The most accessible illustrations of the ancestral races, their hybrids and the closely related and occasionally released Green Pheasant (of Japan) are in the Heinzel field guide.

The second oldest introduction belongs to the Canada Goose, known in Britain from 1678, and breeding on many estate waters a century later. The mind boggles at the thought of the first captives forced to brave the Atlantic swell under sail!

Like the Pheasant horde, the population of 35,000 birds [now thought to be breeding 54,000 pairs] is of mixed race. Most are clearly of the east Canadian form, but arguments have been put to suggest that some of the original introduction were of the largest Nearctic subspecies, while continuing escapes and occasional vagrants – flying down the vector of the Greenland White-fronted Goose – muddy the waters as well. Thus, birdwatchers are set some really teasing puzzles by the Canada Goose tribe and are not helped in solving them by the flux in systematics that continues.

I shall never forget the bewilderment of seemingly seeing no fewer than three races in seven birds among the Greenlanders of the Wexford Slobs on 18 November 1969. It was as well that I had Bob Emmett and Oscar Merne, then the Warden of the Slobs, to calm me down. My local birds are clearly east Canadian in the main but have twice presented individuals resembling other forms.

The third and fourth introductions were those of the Egyptian Goose and the Red-legged Partridge, both begun in the 18th Century and from 1770 in the latter’s case. The goose was not accepted as successful as a “gentleman’s seat” symbol by the Handbook, but over the last 50 years, it has fully adapted to life in East Anglia where there are now 500 birds [and now nearly 2,000 breeding pairs]. Without trying, on a September Norfolk holiday last year, I saw three families from the car!

As Bird Watching has already discussed, the “Frenchman” – as the Red-leg was affectionately nicknamed – is now subject to the intersperse of the closely related Chukar, and a hybrid between the two species, the so-called Ogridge. The last two are reared and released by game farms. Hopes that this threat of genetic confusion would soon cease have not been fulfilled. Even in Staffordshire – hardly a classic partridge county – Chukars now stroll about and so partridge sightings no longer give us a simple choice between the indigenous Grey and the single import Red-leg. The total incidence of Chukars and hybrids in the 400,000 Red-legs is just not known [probably now very close to zero].

As the last two species were being introduced, our indigenous Capercaillies were fast approaching extinction. In the last 30 years of the 18th Century, the felling of mature coniferous forest provoked its death, first in Scotland and then in Ireland. it had already been gone from England for a century.

Once again, however, sporting Man saw to it that the most majestic of his gamebirds was not absent for long. In 1837, Swedish birds were released in Perthshire and later throughout the remaining Scottish forests. The biggest grouse in the World was back! It bred well and with its reputation as a target enhanced in the 1960s redeployment of commercial shooting, it became common in the 1970s.

Even so, the Capercaillie retains its dependence upon mature, open woodland with a ground carpet of blackberries particularly crucial in high fledging success. Since modern afforestation delivers little more than serried ranks of exotic conifers and a dank bed of dead needles, the 2,500 birds [now down to about 500 birds] are far from safe.

The releases of the Little Owl did not begin until 1843 and were unsuccessful until 1874. Six years later, unaided spreads began and these achieved real momentum around 1910. The occupation of southern and midland England and most of Wales was completed in the next 20 years. There are now about 30,000 birds (now thought to be about 3,600 breeding pairs].

The Handbook conceded that both the Red-legged Partridge and the Little Owl might occur as wild birds.Sadly, we seem to have given up on such issues these days. One exhausted Little Owl on the Dungeness shingle is all that I could contribute to a modern re-examination.

Much more significantly, the Game Conservancy has pointed out that flight in Alectoris partridges is for escape, not migration. According to G.R. Potts, the Red-legs’ chief modern student, movements over the Channel or North Sea are “physically impossible”. Incidentally, the lack of sustainable flight power affects Pheasants, too. Maury Meiklejohn’s observation of one landing on an offshore rock was once posted as the only interesting thing that the species had ever done; but, in fact, the Handbook did note the exceptional crossing of up to four miles of water.

Here we should also note that, historically, one other gamebird looked set for a place on the British list but failed to secure it. This was the thick wood-loving Reeve’s Pheasant which became apparently acclimatized and common in the Scottish Highlands between 1870 and 1895, but then simply evaporated. A second attempt to put down this fine bird was made in 1969-71 but again, without lasting success.

In the last half-century, five other species have established feral populations and so forced their way into Category C of the British list.

Four have come from the continuing human purposes of live ornament collection or sporting entertainment. The first is the exquisite and gutsy Mandarin. Gutsy?! Without doubt. In its home range, it is a true migrant and birds from British captive or feral groups have dispersed as far north as the Faroe Islands and as far east as Hungary. Two did 900 kilometres in a day in November 1962, leaving Oslo in high hopes of a warmer winter to the south, only to be gunned down in Northumberland!

There may now be more than 2.000 Mandarins in Britain [now thought to be at least 4,400 pairs]. I well remember my excitement when two pioneers reached Chingford Pond in Epping Forest. They are now regular there, in flocks!

Less exquisite but equally brave (and more amusing) is the Ruddy Duck. For its growing presence, we have the success of captive wildfowl breeding programmes to thank. Even after 25 years of watching it on English waters, this stifftail still does not seem right to me but clearly it has escaped for good. About 1,800 birds now exist outside collections [now almost completely exterminated after sustained efforts by DEFRA to remove a potential threat to native European White-headed Ducks, through interbreeding]. Five miles from my current home, Blithfield Reservoir hosts one of our biggest winter flocks and birds from it visit several of my ponds, breeding in autumn on two.

Next come two more Chinese pheasants, the delicate and highly decorative Golden and Lady Amherst’s. Their numbers are estimated at respectively 1,500 and 350 birds [now c15 male Golden Pheasants and no Lady Ameherst’s Pheasants]. The Golden is widely scattered from lowland Scotland south but the Lady Amherst’s remains locked into two estates and their surrounds. Its original escape came from Woburn in Bedfordshire.

Last of the five – only admitted to the British list in 1983, comes the most irrational of all our feral birds. It is the screeching, fast-flying, fruit-eating (and -destroying) Ring-necked Parrakeet. With its obvious pest potential, this bird could soon be our most beautiful avian nuisance. Although ancestrally a tropical animal, the parrakeet has, like the Collared Dove, the genetic resources to overcome the stresses of more northerly and colder latitudes.

In 20 years, a few pockets in south-east England have produced at least 1,000 birds [now, about 9,000 pairs]. I well remember flinching at the sight of one powering north over my home at Hessle, North Humberside in 1976. “Go home to Africa”, I shouted after it. It did not and will not!

Here endeth the list of the 11 feral breeding species that occupy Category C of the British list. Not every ornithologist or birdwatcher applauded this extra list dynamic when it was adopted by the BOU in 1970 but it does make sense. Altogether, the winter populations of its members approach 8,500,000 birds and we must keep our eyes on them.

Do we face the prospect of more Category C species? Well, it does look as if the Chukar might be forced upon us but otherwise I am happy to write that candidates appear few and far between. Even so, we should all be aware that 10 years ago, the Winter Atlas searches turned up between 10 and 30 individuals of flamingo (in various guises), Sacred Ibis, Black Swan, Bar-headed Goose and Wood Duck, while other collected wildfowl are still allowed to rear free-flying young. Already, the goose is accepted as feral in Scandinavia. I would prefer it to the angry Black Swan, a nasty predator of other waterbirds!

Happily, the Bobwhites and Budgerigars of Tresco have failed to get a proper grip of the Monterey Pines and subtropical gardens, but you never know!

When it comes to mere accidental escapes, the list is much, much longer. In the 1970s, at least 97 imported cagebirds were seen “in the wild” and most feet-using observers now find their paths crossed by escaped cagebirds at some time or other. Increasingly, county bird reports list such wanderers, and it is clear that Budgerigars, parrots, Cockatiels, weavers and other finch-like passerines are the commonest causes of the “What on earth is that?” question.

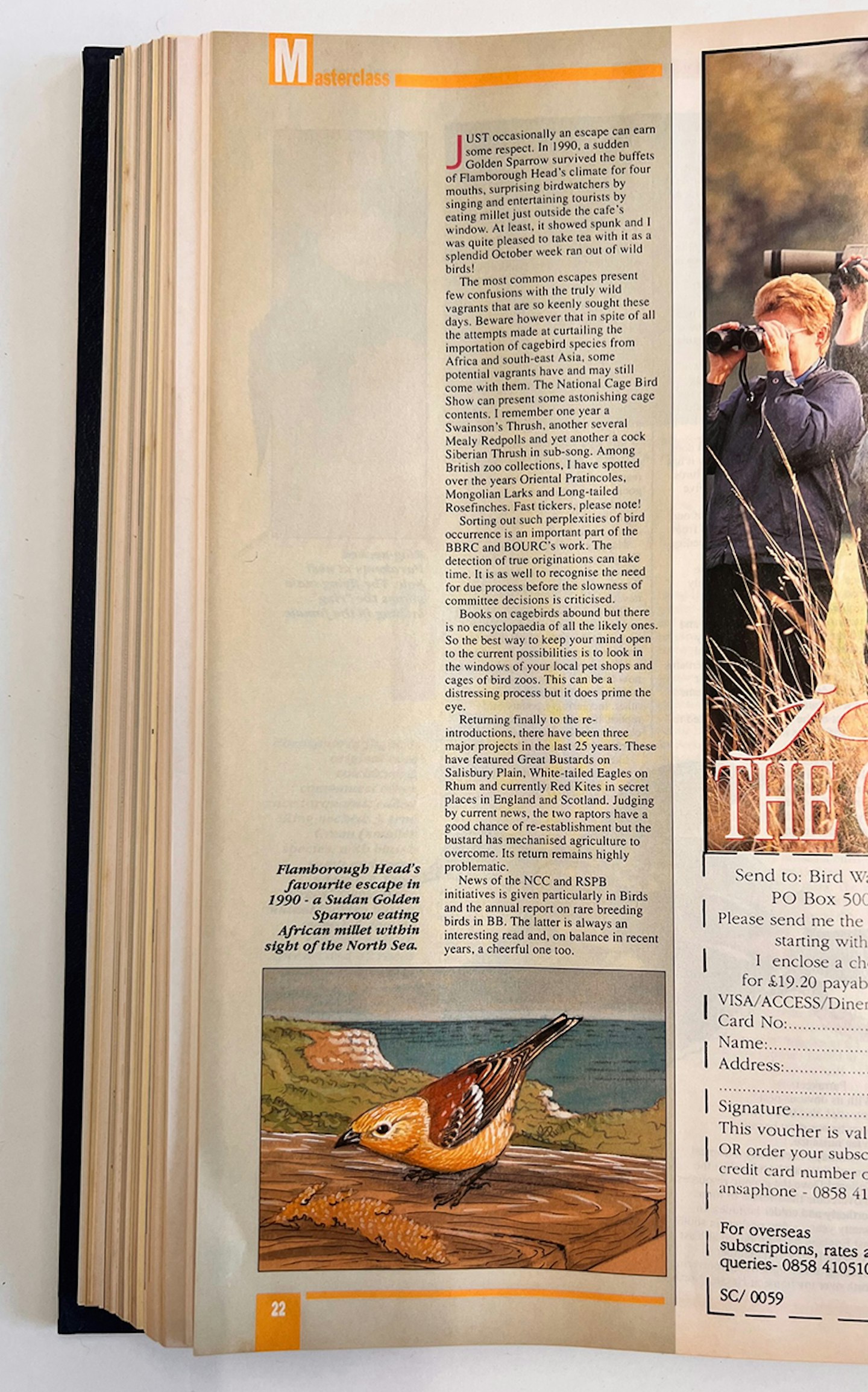

Just occasionally, an escape can earn some respect. In 1990, a Sudan Golden Sparrow survived the buffets of Flamborough Head’s climate for four mouths, surprising birdwatchers by singing and entertaining tourists by eating millet just outside the café’s window. At least, it showed spunk and I was quite pleased to take tea with it as a splendid October week ran out of wild birds!

The most common escapes present few confusions with the truly wild vagrants that are so keenly sought these days. Beware, however, that in spite of all the attempts made at curtailing the importation of cagebird species from Africa and south-east Asia, some potential vagrants have and may still come with them.

The National Cage Bird Show can present some astonishing cage contents. I remember one year a Swainson’s Thrush, another several Mealy Redpolls and yet another a cock Siberian Thrush in sub-song. Among British zoo collections, I have spotted over the years Oriental Pratincoles, Mongolian Larks and Long-tailed Rosefinches. Fast tickers, please note!

Sorting out such perplexities of bird occurrence is an important part of the BBRC and BOURC’s work. The detection of true originations can take time. It is as well to recognise the need for due process before the slowness of committee decisions is criticised.

Books on cagebirds abound, but there is no encyclopaedia of all the likely ones.So, the best way to keep your mind open to the current possibilities is to look in the windows of your local pet shops and cages of bird zoos. This can be a distressing process, but it does prime the eye.

Returning finally to the re-introductions, there have been three major projects in the last 25 years. These have featured Great Bustards on Salisbury Plain, White-tailed Eagles on Rhum and currently Red Kites in secret places in England and Scotland [now not so secret!]. Judging by current news, the two raptors have a good chance of re-establishment but the bustard has mechanised agriculture to overcome. Its return remains highly problematic.

News of the NCC and RSPB initiatives is given particularly in Birds [former RSPB membership magazine, now called Nature’s Home] and the annual report on rare breeding birds in BB. The latter is always an interesting read and, on balance in recent years, a cheerful one, too.