To split or to lump?

April 1991

This month, Ian Wallace returns to more controversial ground and remembers his steps through the species into the vexed world of subspecies.

Richard Richardson, late of Cley, was usually mild-tempered but one Autumn day, back in the 1950s, Bob Emmett and I found him with a very angry look on his face. His terrier was miffed, too.

Enquiring about the cause of Richard’s displeasure, we learnt that he had answered a “we have a rare bird in the hand – need you to confirm it” signal from halfway down Blakeney Point, only to find the bird no more than half a Siberian Lesser Whitethroat.

“Half?” you ask.

“Yes”, I have to answer, “subspecies have the habit of vexing their observers and ringers by failing tests – and therefore being of no real value”. Certainly, Richard’s umpteenth trudge along (or is it, through?) the Cley shingle to find the right feather formula on only one wing had been a waste of time.

Nevertheless, the radiation of species into subspecies is a fascinating subject. I put it firmly on my ornithological curriculum in 1947, in which year I first read every last word in the ‘old’ (actually second oldest) Handbook.

Being then of the age when my collecting instinct was marked, I became transfixed by the penultimate section of the last volume. This contained a “Systematic List of British Birds”, which then included 520 forms disciplined by order and family (beginning then with the intelligent crows). Their names were qualified by notes on British and Irish status and the whole feature occupied a tense 37 pages.

On the second page, I noticed that the Jackdaw was listed in two forms. Reading on, I discovered that nearly 60 other species appeared at least twice, while many others had three Latin names, not just two. Puzzled, I searched the Handbook for an explanation of this phenomenon and found it in the realisation that the species was not the end unit in evolution. Seemingly, the subspecies was.

Over the next five decades, I have learnt that the subspecies is a wobbly concept. In truth, it is not the natural unit (or building brick) of systematics, and opinions on its usefulness vary widely. It is better considered as a “practical device” for the description of those parts of a species’ population which differ sufficiently (75% is a common test) to be distinguished, morphologically.

Subspecific differences are most visible in size, plumage colour tones and (more or less) geographical range. The first two variations are predominantly the product of range, particularly where habitat or climatic changes affect the species.

The terms race’ or ‘geographical race’ are used synonymously with ‘subspecies’. Most modern birdwatchers would settle for ‘geographical race’ as the most useful interpretation of the concept. “Splitting” or the most extensive – some would say excessive – description of subspecies was characteristic of most taxonomists in the late 19th and early 20th Centuries.

Of recent British ornithologists, the most prolific author of subspecies was P. A. Clancey. In the 1940s, he discerned morphological (mainly colour) differences in several populations ignored by the Handbook. Even within the British mainland, he proposed for example a new Bullfinch race from Perthshire and new Greenfinch forms from Lanarkshire and Wiltshire!

The converse of “splitting” is “lumping” or the realisation that since every individual bird is a mite distinct from the next, there has to be a limit to the wholesale converting of mere pockets or shades of differences into real dichotomies.

In the 1950s, Professor Ernst Mayr (of successive German, Swedish and American universities) poured a cold shower onto “splitting”. He forced attention to the fact that the proving of significant geographical variation suffered from several weaknesses, of which the most serious was the sheer subjectivity of taxonomic eyes and pens. Adventurers like Clancey saw many of their races sent back home to the mother species.

In the last three decades, interest in subspecies has become fitful and localised. Rather strangely, the only major new examination of them has come from another American author, the late Charles Vaurie, who surveyed the radiations of all Palearctic birds in two classic volumes – passerines in 1959, non-passerines in 1965.

For the Western Palearctic, BWP has since 1977 been offering summaries of all references and intelligent discussion of these, rather than further opinions.

For Britain and Ireland, there has been no full review since 1971 when the BOU published the status of all species up to 1970 and redefined the associated subspecies. Several of the Handbook’s races disappeared without trace of published reason!

With the collecting of specimens virtually outlawed by modern law (and philosophy), the radiation of our own birds into local forms is now apparently ignored. Yet ,in a mere 10,000 years, since the last Ice Age, at least 28 species have shown racial divergence – five times or places in the case of the humble Wren! – and so a remarkable piece of evolution study is being lost.

Nobody would cheer if the shotguns came out of their cases, but it is odd how the establishment of field record review has also backed away from the issue. Its attitude to subspecific claims has shifted from the increasingly confident (in the 1960 heydays of the observatories) to the trembling and selective (in the 1970s) and on to the seemingly traumatised and neglectful (now).

Apart from a few amazing promotions to species, for example the dispersed scrum of Rock, Water and Buff-bellied (American Water aka American Buff-bellied) Pipits and the bewildering twigs of the Crossbill branch, the only subspecies monitored regularly in the current national literature are the 10 or so which feature in the annual Rarities Report.

It is entirely unclear to me how we are staying in touch with the total British and Irish target group. With only a touch of imagination, this can be assessed at 125 or so races spread from Greenland to Siberia. I accept that the late, august B. W. Tucker, writing as editor of British Birds 40 years ago, warned field observers off over-indulgence in subspecific identifications.

Nevertheless, some of us who learnt of them from the old full references and then caught and measured them at observatories find their study hard to forsake. Some races signal long isolation in restricted habitat – the oat-mealy St. Kilda Wren is the classic example of this class.

Others cast clear light on the source of migrant falls – the swarthy Icelandic Redwing is such. A few act to make even a dull winter day bright – witness a big Mealy Redpoll among local finches – the “zebra” stripes on their flanks and the “swarthy” robustness of their general character, all brilliantly portrayed in a Richardson drawing in the log. Never forgetting these tell-race characters, I have since been confident of four strays as far south as St Agnes, Scilly.

The Greenland Wheatear and Redpoll form obvious ends to the range of their species’ appearances (or clines). Both are dogged however by intermediate forms in Iceland, and in the case of the Redpoll, by the odd large individual that has bred in northern Scotland.

So there is always the risk of such confusions attaching to field claims. But surely it is not so high that all records should be considered worthless or, at best, treated erratically.

Happily most counties persist in reporting Greenland Wheatears ,but I will bet that any student of the status of the Greenland Redpoll will find that, except in the northern isles, it is hardly looked for, let alone reported or accepted. Its regular winter quarters in western Europe remain unknown. As long as we chase pretty but irrelevant waifs like Yellow-throated Vireos before more meaningful bird targets, they will stay so.

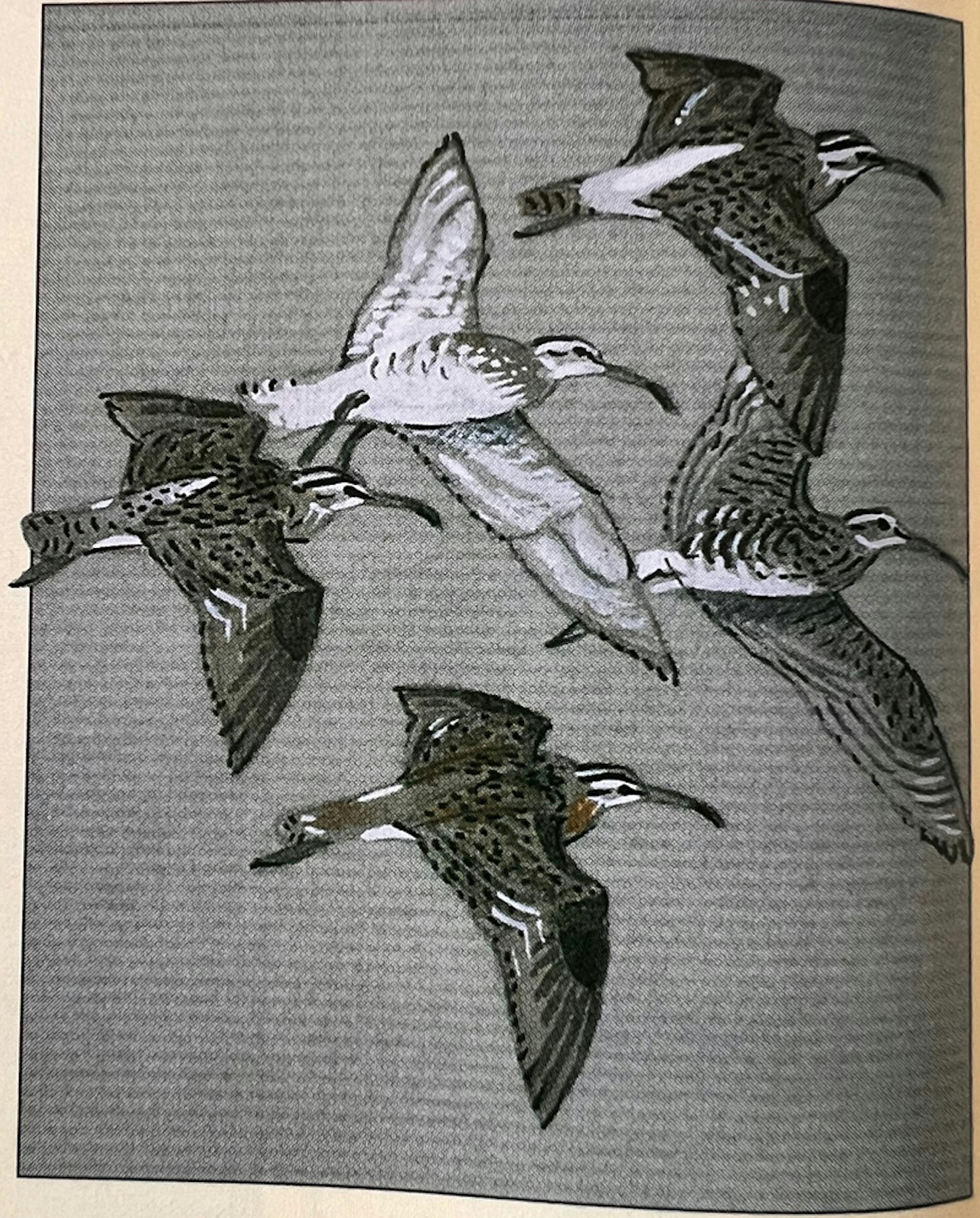

In May 1955, an odd Whimbrel landed on Fair Isle; it was given close scrutiny and identified as the Nearctic race hudsonicus, entering the British list of subspecies. A second bird appeared in Co. Kerry in October 1957 and another has since reached Sierra Leone. All three showed a dark rump, the supposedly unique mark of the Hudsonian Curlew (American name), but how many of us know that this character is also shown by the Whimbrels that breed in eastern Siberia?

What, therefore, of the dark-rumped birds that have recently occurred on the east coast? I have seen two and both were in the company of other waders that had flown west, not east. Nor are such birds the end of odd Whimbrels. If you see a pale one, do not forget that south of the Urals lurks a form with an even whiter rump than our race and with a pale underbody and underwings to boot. One such bird sat on Flamborough Head for six days one October, but alas ,I could not get anyone else to take it seriously!

The autumn influx, rare wintering and occasional spring falls of the so-called Continental Robin (Erithacus rubecula rubecula) have never been doubted. From ringing recoveries, we know that the birds come from Holland, Fennoscandia, Germany and Poland, but if Pallas’s Warblers can reach us regularly from Siberia, why don’t Russian and west Siberian Robins come, too?

A few east coast observers believe that a few of the requisite race tartaricus do. Certainly, I shall never forget an amazing “blue, orange and white” bird that hid shyly one March in a stream-bed on Flamborough Head. I am sure that Ken Williamson would have rushed for a net, as in fact Andrew Lassey did. Colour photographs of the bird were sent to the British Museum of Natural History but all we got back was a lecture on plumage variation and wear!

There are many other recent cases where the chance of pinning a sharper origin on interesting vagrant races has been lost, but let me return to assisting you to learn some of the commoner subspecies. The most easily available are those of the Herring and Lesser Black-backed Gulls – roosts and especially at food sources like rubbish dumps; the continental Chaffinch – in winter flocks, especially when Bramblings are present; and the continental Robin – in dense cover, especially over water. All of these penetrate into Britain in Winter and present the all important opportunity of easy field comparison with British forms at close range.

Unfortunately, references to subspecific appearances are not in the front rank of current identification literature. So you will have to ditch your field guides and resort to older or more spacious books, like Wardlaw Ramsay, the Handbook, BWP, Vaurie and the modern “identification monographs” on bird families.

The best plumage texts are in the Handbook; the best illustrations and measurements there, in BWP and (less complete) the monographs. Vaurie assumes you know the species or nominate (first-named) subspieces and gives you few measurements; he does however set subspecies fully in their clines.

I have to stress that to perceive the subtleties of subspecies, no book can substitute for the close study of skins or live birds. So regular visits to museum collections or ringing stations are crucial to sharpening your eye and disciplining your visual memory.

Remember, too, that claims of most subspecies will have to go through the record review mincer even more than those of rarities.

Recorders and committee members will need to be impressed with really detailed notes which must include close comparisons with the common subspecies to have any hope of success.

Do not be surprised if even those that are accepted are published with the caveat of “showing the characters of”. The main thing is to get them into the literature and leave a greater validity to the later timed analysis of all such records which, I hope someone will take up in due course.

By now, you will know that I am distressed by the current neglect of subspecies. As “practical devices”. they have a place in birdwatching but they are not for the faint-hearted – in the field or in the committees!

P.S. No new races in recent years? Wrong. Irish gull specialists photographed an American Herring Gull in the early Winter of 1986 and the FOG-gies gathered Nuthatch four years ago. What else are we missing?

2020s update

Since DIMW wrote this article plitting of subspecies and the further splitting of such into full-flown species has come (back) into vogue. This applies not only to birds but across most fields of taxonomy. Among British birds, since this article was written, the redpoll complex has been split so that the smaller, browner birds we call Lesser Redpolls are now a distinct species from the larger, paler Mealy and ‘Greenland’ (aka North-western) birds known as Common Redpoll (though for how long this will remain so remains a mystery).

Other groups have gone through revolutionary taxonomic revisions, including the ‘large white-headed gulls), with the splitting of Herring Gull into such recognised species as Yellow-legged Gull and Caspian Gull (as well as the American Herring Gull, mentioned by DIMW). There are plenty of other examples, proving the value of closely scrutinising ‘different’ birds.