Broaden your horizons

February 1991

Open country and water can be surprisingly full of birds. In any kind of weather, their watchers are often very visible on the skyline; in wind or under precipitation, they can be truly exposed. Here, Ian Wallace discusses long-range scanning, hard slog searches and keeping warm.

IT WAS before the war (WWII) and in the wide vista of Shetland and its sea that I first noticed birds. With scarcely a bush above stonewall height and only one conifer plantation in the whole archipelago, it was wide horizon watching or nought. No Blue Tits but Solan Geese (Gannets), Tysties (Black Guillemots) and Bonxies (Great Skuas) galore!

Getting close to northern birds was no problem. There was a tameness about Shetland’s birds that brought Arctic Terns to hover by our cottage windows and Gannets to fish among the drifters (ancient Herring boats lacking the echo screens and dreadful purse nets that have since decimated fish stocks).

In a small launch called ’Skylark’, we would go out to watch auks and Shags – and one heart-stopping morning a Killer Whale – fishing in crystal water. I do not remember any particular event – except Orca! – but the general idyll has me still enthralled.

When, in the 1940s, I grew up into a diary-keeping Junior Bird Recorder, our changes in domestic location meant that open country or water experiences became fewer, but regular visits to Norfolk and deepest Cornwall, particularly the Helford River, kept my love of wide horizons alive.

Looking back from my current, much tamer, farmland station, my memories of wilderness are inevitably rosy, but not so much so that I have forgotten the hard slogs made within them. So, I thought that I could help you if I distilled from my logs some advice on how to tackle birdwatching against wide horizons. Here follow five pieces.

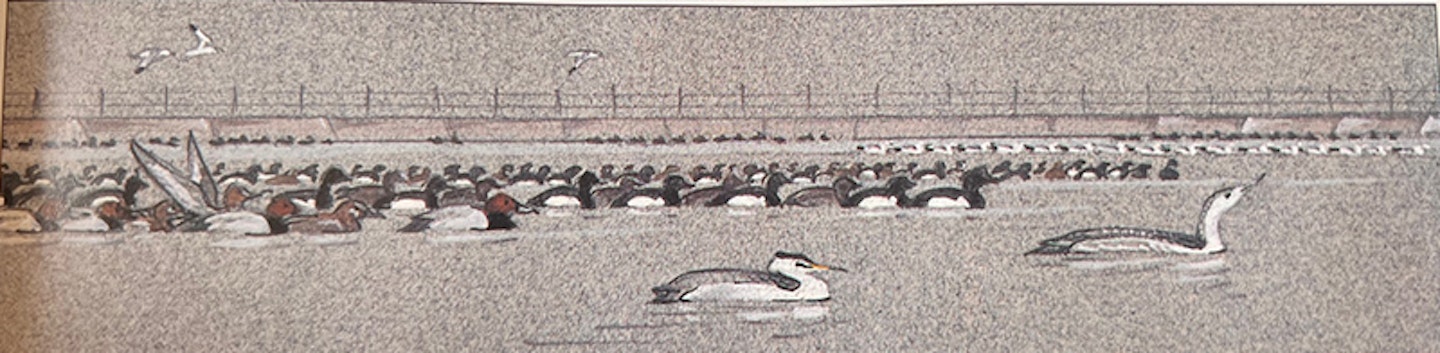

1 Watching large inland waters

I learnt my wildfowl on London reservoirs, particularly the excellent Barn Elms complex particularly the excellent Barn Elms complex alongside the Thames opposite Hammersmith. The lay-out of the four main squared waters and their cruciform banks meant that most birds were well within binocular range. This was not the case at Staines, or the other large waters that I watched in Middlesex and Essex.

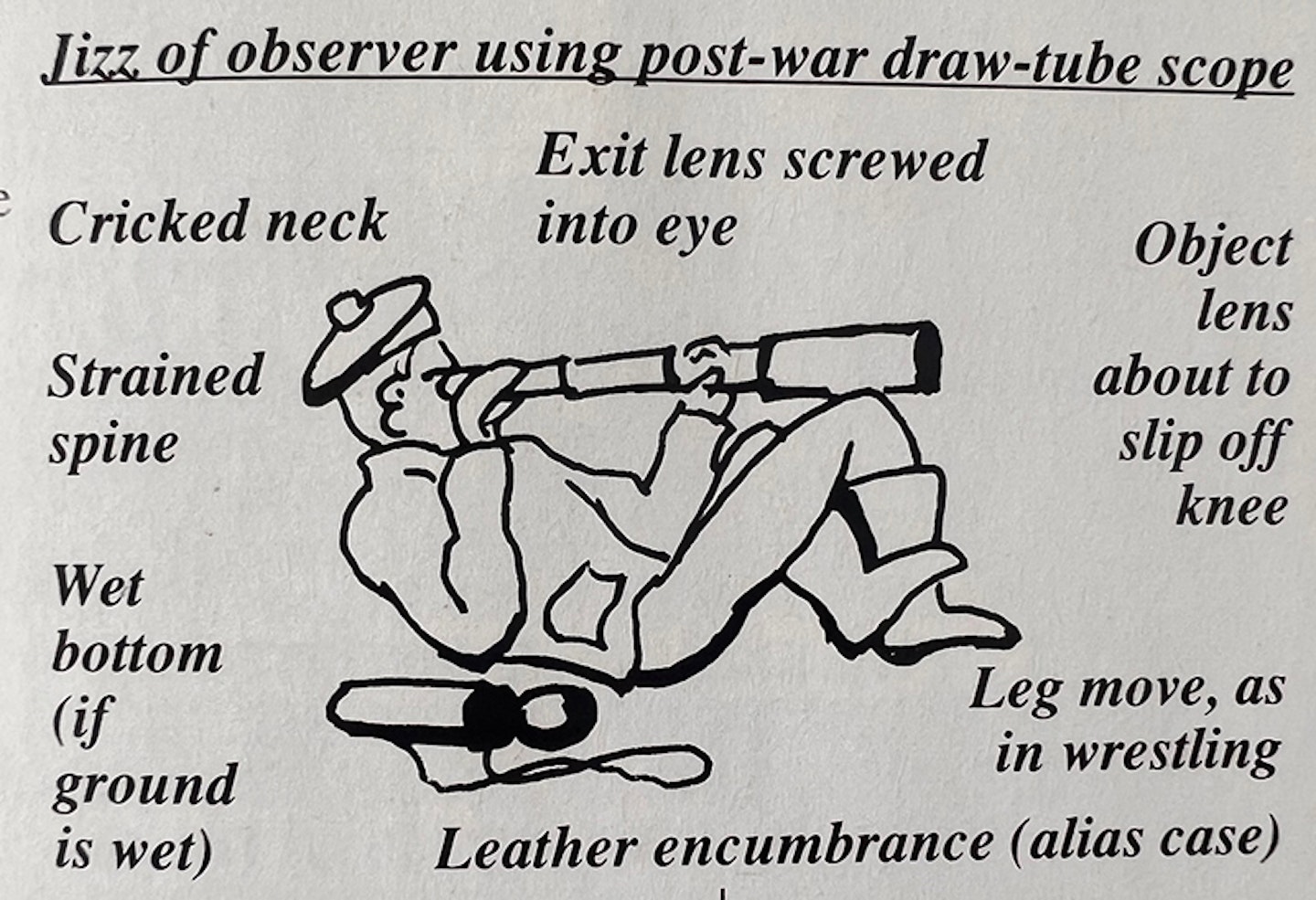

So came another hole in Dad’s pocket and my introduction to the telescope – an instrument that I heartily dislike (as looking down one always makes my eyes behave like fruit machine dials!), but which I have to admit is crucial to long-range observation.

These days, telescopes are somewhat handier objects than they were, ignoring, of course, the now obligatory trendy tripods. In the 1950s, we spurned the last, pulling out our rustic draw tubes, resting them on walls or fences, or our knees, in Yoga-like postures no longer achievable by modern birdwatchers.

The main trick with a telescope, facing a large water and distant dots, is to find a watchpoint with no windshake and a good light angle, with the brightest source behind your shoulders. Get the light angle wrong and the power of your burner (old slang for ‘scope’) will only blow up harsh and dark images into worse identification tasks.

Greater magnifications can also depress your perception of behaviour and general character (‘jizz’) so we always scanned distant blips with eye and binoculars first. In that way, we perceived, for example, the tighter pack formation of Teal within a spread mass of larger duck, the abrupt tail-lessness of a large grebe compared to the sleek end of a diver and the higher waterlines of some gulls.

Even within the most dramatic gatherings of wildfowl and other waterbirds, individual species have a habit of staying apart, standing out. Learning to spot the odd bird(s) out is an important skill, part of the all- round awareness of a ‘trained soldier’. Just screwing your eye into a scope and ploughing into a mob of birds is not a sensible tactic; it is a recipe for missed birds.

When watching birds on water, beware, too, the illusions and distractions provoked by the differing background motions and colours against which your quarry is displayed. Bright, sun-reflecting water burns off the edge of images, thinning bills in particular. Small ripples enhance size and can alter apparent head and bill carriage. Waves can mask diving birds for irritatingly long moments. Grey water allows accurate colour reading; dark blue is deadly, for the dark bits of distant plumages become virtually invisible.

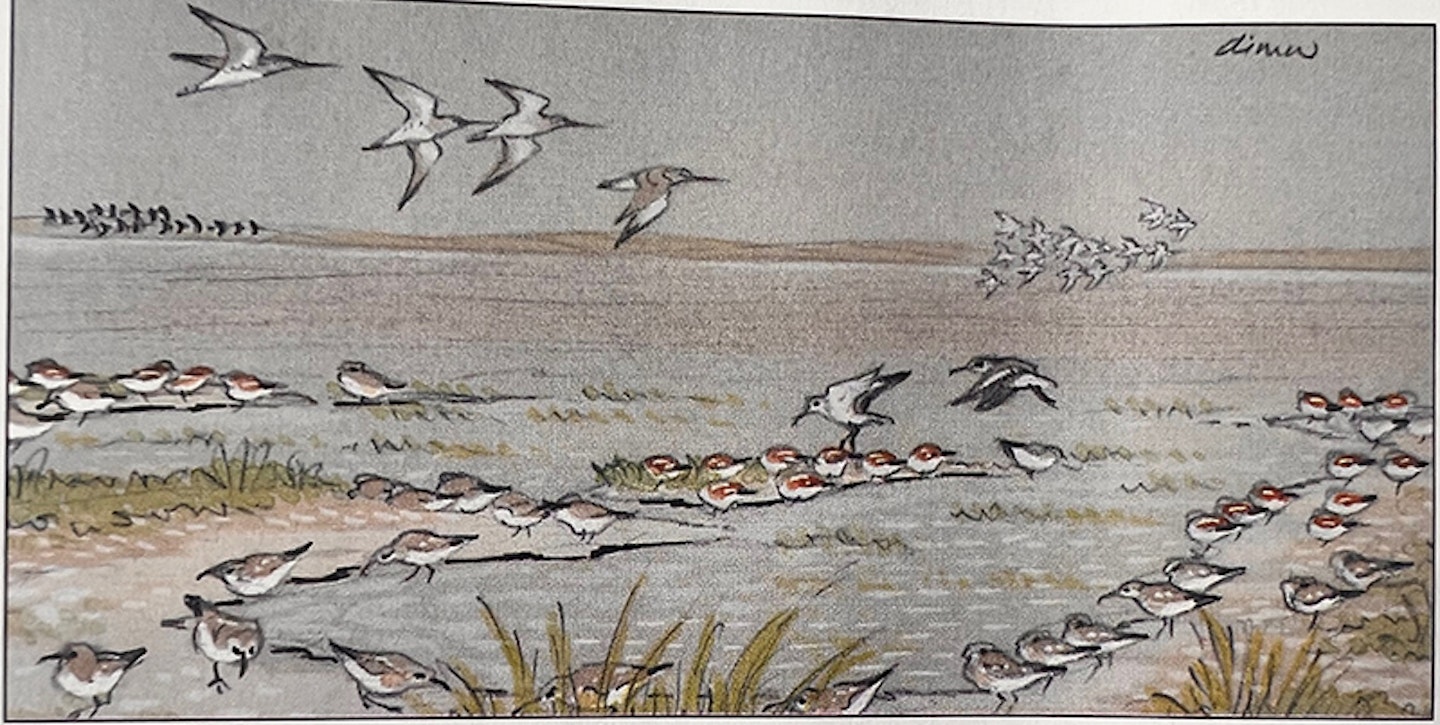

2 Watching estuaries

Estuaries are exciting places, with far more niches along or in them than those visible at first sight, and with the tide producing a twice-daily stimulus to bird movement and roosting.

Again, I have to own up to the indispensability of a telescope for most observations, but it is possible to get close to estuary birds. The trick is to find the areas where they roost at high tide and where they feed close to salting edge, when the monthly tide cycle softens the highest mud strata.

Where estuary watching has worked best for me has been on the Upper Severn (as noted last month) and along the Inner Humber between Brough Haven and Faxfleet. At the last places, I found that by working the higher tides, I could walk gently along a compressed strip of still-feeding birds, lie hidden by their eventual roost or (when lazy) stay in the car and scan the nearest plough for the plovers that always left the estuary for a proper rest.

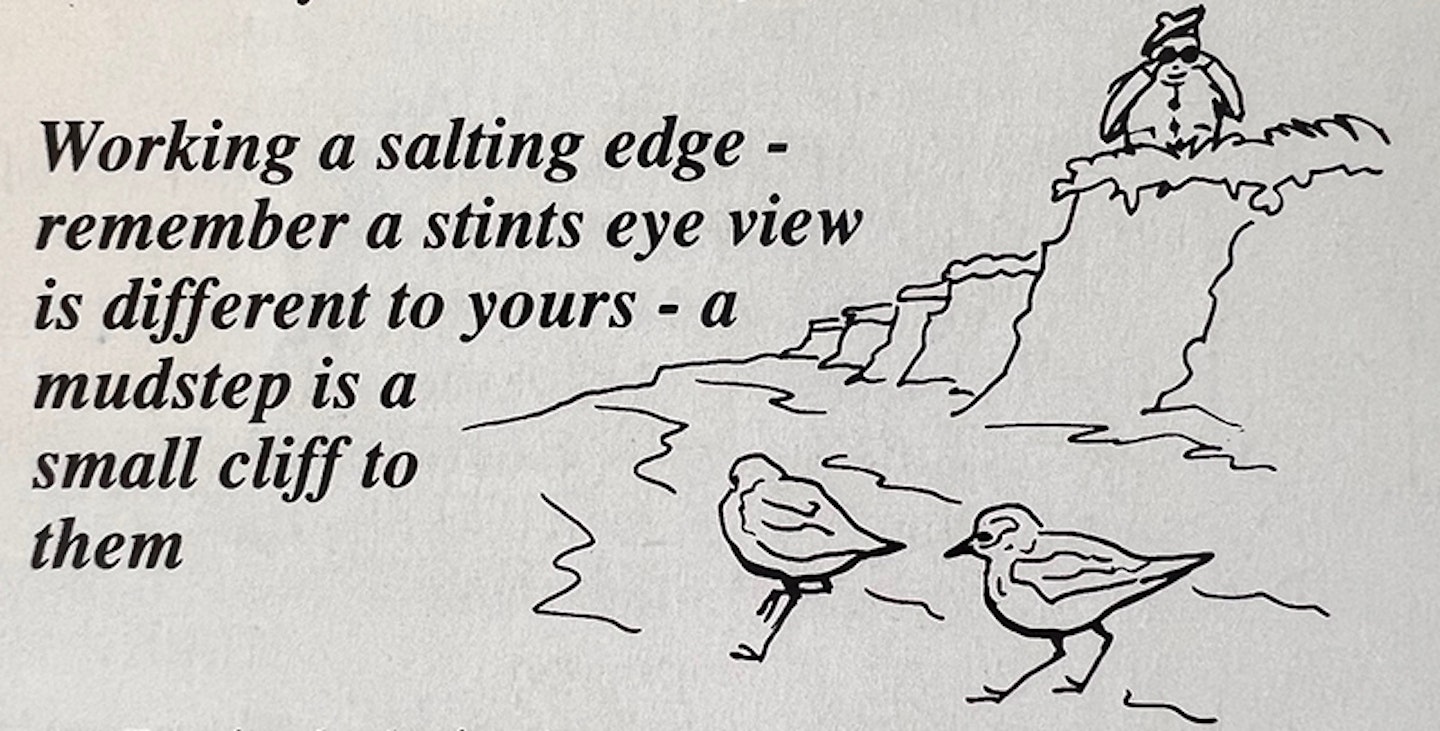

Particularly in Autumn, when many waders are young birds with no knowledge of man, the “gentle walk” tactic can give marvellous results. To have Little Stints and other globe-trotters probing mud a few yards from my wellies – so that the distinction of the tell-tale dull inner wing-coverts and tertials of a Red-necked was possible – was a fantastic experience.

To enjoy it, however, you have to achieve complete familiarity with your chosen spot. Try to keep the wind on your face and the birds, and as much light as possible behind you. Walk slowly along the salting edge, not directly at it. Think kind thoughts (it seems to work!). Charge and the birds will be a distant whirr in seconds.

The trick with a roost is to get to it early, before the water and birds come, and stay late, until they have gone. Do not risk exploding one at high tide point. You will lose the birds (and break the law). The snag with a roost is the dense packing of birds upon it. Hence, all the more reason to watch them all come in and all go out. A quick look will miss birds, perhaps the best.

Tide watching is fun, too. Both on the Severn and the Humber, I found that the higher tides nearly always brought good birds with them and past me, especially during or just after gales. Effectively, you can nearly always combine tide and roost watching. It means juggling constantly with scope and binoculars but you will learn to manage that with practice.

For this type of birdwatching, a small book is imperative and that is the annual tide table for your nearest harbour. Without it, you will find yourself constantly frustrated; with it, you can judge your arrival to within a few minutes.

3 Watching heath and moor

In open country with low, seemingly uniform vegetation, a static scan can produce excitement, but usually you have to be active in your search for birds, particularly if you want to see all the likely species of the habitat.

There is, however, no point in blundering off towards the horizon. So it is important first to understand that even apparently homogenous tracks of ground have subtly different zones and reliefs within them. Thus a heath ridge may have open patches of earth with annual plants, a grouse moor will certainly combine tall, short and burnt heather and even the “barbed wire” of gorse is not completely impenetrable. Such breaks in uniformity provide differing plant and insect flora and long before you can spot them, the birds will be exploiting them.

The best tactic is to take a long look at the area to be explored and to plan a route through it that is effectively a cross-section of all its zones. For a heath, it could be: start with that slight ridge to the right, move down past those grass patches, skirt the gorse clump, check the stream, cross it, push through the deep heather to the left, check the birch clump and end up on top of the next fold.

It does take years to read landscapes quickly for birds. Remember, practice makes perfect. As elsewhere, watch the light source, use dead ground or the “forward” sides of slopes to reduce your skyline prominence and never rush. Meadow Pipits will usually get up and ‘cheep’ at you ,but Stonechats do not always ‘chack’ noisily, Stone-curlews can just freeze. Always give birds in open country time to go about their business.

4 Watching coastal wilderness

Open country along coasts is usually long and narrow in aspect. So, once again, you have to be active in searching, indulging more in the “long, hard slog” than anywhere else.

For this reason, I prefer to have the wind on my back and in winter, that ploy often requires a pitch-black trudge upwind before dawn. Incidentally, it will lose you most other observers, too!

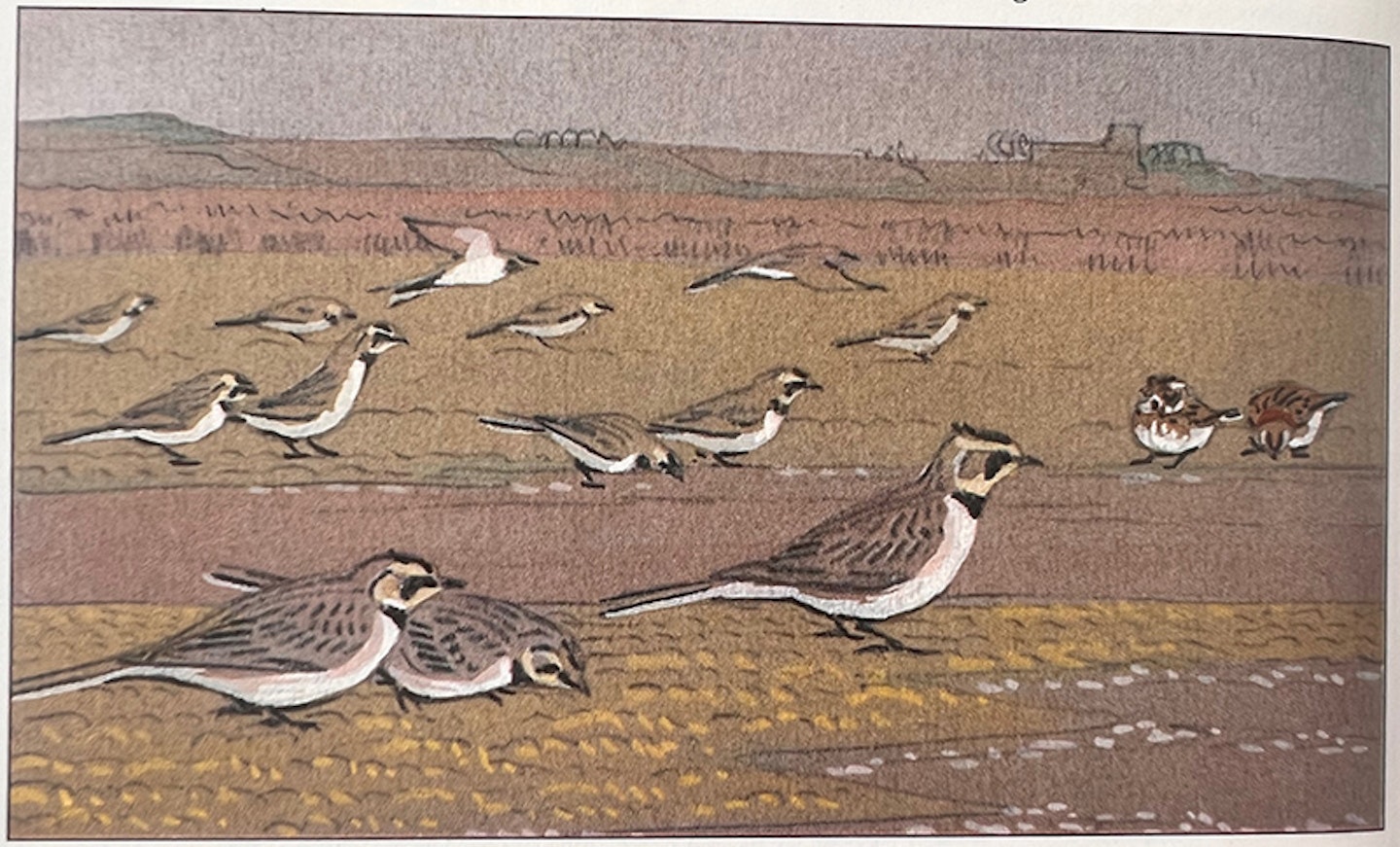

The benefits of extra effort on the coast can be considerable. Hundreds of fog-bound Snow Buntings along Blakeney Point, the Avocets of Butley Creek, scores of Shore Larks at Salthouse, more than 100,000 migrants between Bempton and Flamborough Head, teasing “probables” like a Saker and another day a gale-whipped Long-toed Stint at Rattray Head – those are just some of my certain and uncertain memories of shingle, sand, cliff-top and salting struggles over the last 40 and more years.

Since there is usually some extra wind along coasts, make sure that you search every lee – the back of dunes, the quiet side of sueda bushes, even the lip of a salting can all give extra shelter to birds. So, do not walk a straight line; try always for a cross-section of all ground reliefs. Just don’t fall into a creek!

Look, too, for food concentrations. These often occur in lees but they always exist in the wrack of the last tideline and in the patches of annual plants. Remember too to look ahead for bird movement. One wing flicker may belong to a whole flock of Lapland Buntings!

5 Watching large fields

Sadly, monoculture has seen to it that the once small patches of our farmland have become much larger and often hedgeless, particularly is eastern England. Consequently, bird diversity in large fields has collapsed, and the only way that I know to find birds within them is another dose of “long wander”.

It is usually possible to agree with farmers a way through even the hugest prairie. It pays to show them the old paths on the OS maps and then claim right of way. Again, it is important to give as much attention as possible to the few niches that remain. So, even sunken ditches, marl pits, stock ponds, any weedy patch or failed crop, relict hedge clumps, sentinel trees and harvest debris will merit a visit. Birds have the knack of finding every potential source of food and much as I deplore them, the large fields of today can give occasional birdwatching pleasure.

I have found sugar beet – often left long in the ground – to be a magic crop on occasion. It provided Andrew Lassey with the famous 1969 Cream-coloured Courser in Norfolk, and in 1984 it brought me a huge, swarthy Greenland Redpoll in deepest Humberside.

Remember, too, that large fields can be scanned from a car. As I have said before, a friendship with a farmer may grant vehicular access and less slog!

Keeping warm

I present a somewhat tattered figure in the field, being a non-consumer of Barbour jackets, proper walking boots and other specialised clothing. Yet, as here I invite you into open country and its often hard weather, I must warn that care of your own self is necessary.

My rules are simple. Judge the weather carefully; never invite risk. In particular, do not get caught out in long rain, wind-chill or, worse still, both together. Wear or have available a warm hat – heat loss from your head is considerable – and clothe your body with several light layers of cotton and wool.

Do not cocoon them with a squeaking, heavy outer garment on any long march, but depend rather on a thin but close-woven wind-cheater or rubberised smock.

In my experience, it is less dangerous to get slightly wet than to become weighed down, clammy hot, clammy cold and then subject to serious heat loss. With light clothing, you can vary your “walking duvet”, as do the birds themselves; with heavy, you have the problem of what to do with the bit you take off!

As for boots, I am a suede or wellie man. Good pairs of these can still be found at £5.99. Well, it is one way to beat inflation, particularly if you want one really good, warm, light woollie.