Finding a close focus

January 1991

Continuing his recall of past birdwatching initiatives, Ian Wallace tells how a magic spot in seemingly ordinary countryside can produce an unusually sharp focus on avian passage and presence.

Raised largely in London and Midlothian, my early birdwatching in Britain was done in urban oases and lowland hills and along the Firth of Forth. It was not until 1965 that I began to explore our commonest bird habitat – English farmland – but since then, it has received more DIMW footprints than all other types of countryside put together.

As indicated last month, I had been long subject to the examples of my elders, who increasingly espoused conservation, but my addiction to farmland arose from the surveys commanded by the British Trust for Ornithology in the 1960s.

Early in that decade, I was a member of the BTO’s SAC (Scientific Advisory Committee, not Strategic Air Command – that’s in Dayton, Ohio, USA!), and remember well the early debates on the feasibility of mapping Britain’s birds. Nobody was confident about the necessary mobilisation of forces but finally we all agreed that if we could switch our enthusiasm for hunting migrants into fixing the stations of breeding birds, we might surprise ourselves.

We did more than surprise, we achieved. The first summer Atlas crashed all sorts of barriers in observer effort and allegiance. Over the five years from 1968, about 12,500 amateur observers met new disciplines in recording.

Four years later, in 1976, the BTO and IWC delivered a sharper focus on both Britain’s and Ireland’s breeding birds than any that we had dreamt of in the preceding decades. The Atlas project chairman, James Ferguson-Lees, the book’s chief artificers Tim Sharrock (for Britain) and David Scott (for Ireland) and about 150 Regional Organisers had truly advanced our knowledge of bird distribution and its published image.

Another BTO initiative of the 1960s was the testing and positioning of the Common Bird Census (an annual breeding season sample of birds in farmland and woodland plots). In 1964, it also adopted a mapping technique. By 1980, more than 300 plots were being sampled but since then, the number has fallen by a third. The BTO is now expressing particular concern over the decline in sampling in these two habitats.

With the diversity of our common birds virtually impossible to protect in the current conservation regime, this is not the time to give up on the CBC and its sibling Waterways Bird Survey.

I feel some continuing guilt for never having directly supported the CBC, but I have always wanted to assay the wealth of my patches birds throughout the year, to thus end developing the countline method described in the May 1990 issue. It gives broadly comparable results in any season and I complement it with daily migrant searches to keep the chance of the odd excitement high – well, off the floor anyway!

A quite unexpected by-product has come from my field and wood explorations.

This growing proof that within seemingly uniform countryside there are spots which have a peculiar attraction for birds.

I found my first odd, local focus in stock fields north of Slimbridge. There, the New Grounds become Frampton Warth and access to the latter is never curtailed. When in the late 1960s I was trying to beat the Wildfowl Trust to Lesser White-fronted Geese, I also watched the north end of the Severn Estuary. The flood channels of the Warth did not make my searches easy, but by catching the tide and staying hidden by wader roosts, I did quite well, adding Baird’s Sandpiper and several other species to the estuary and county list.

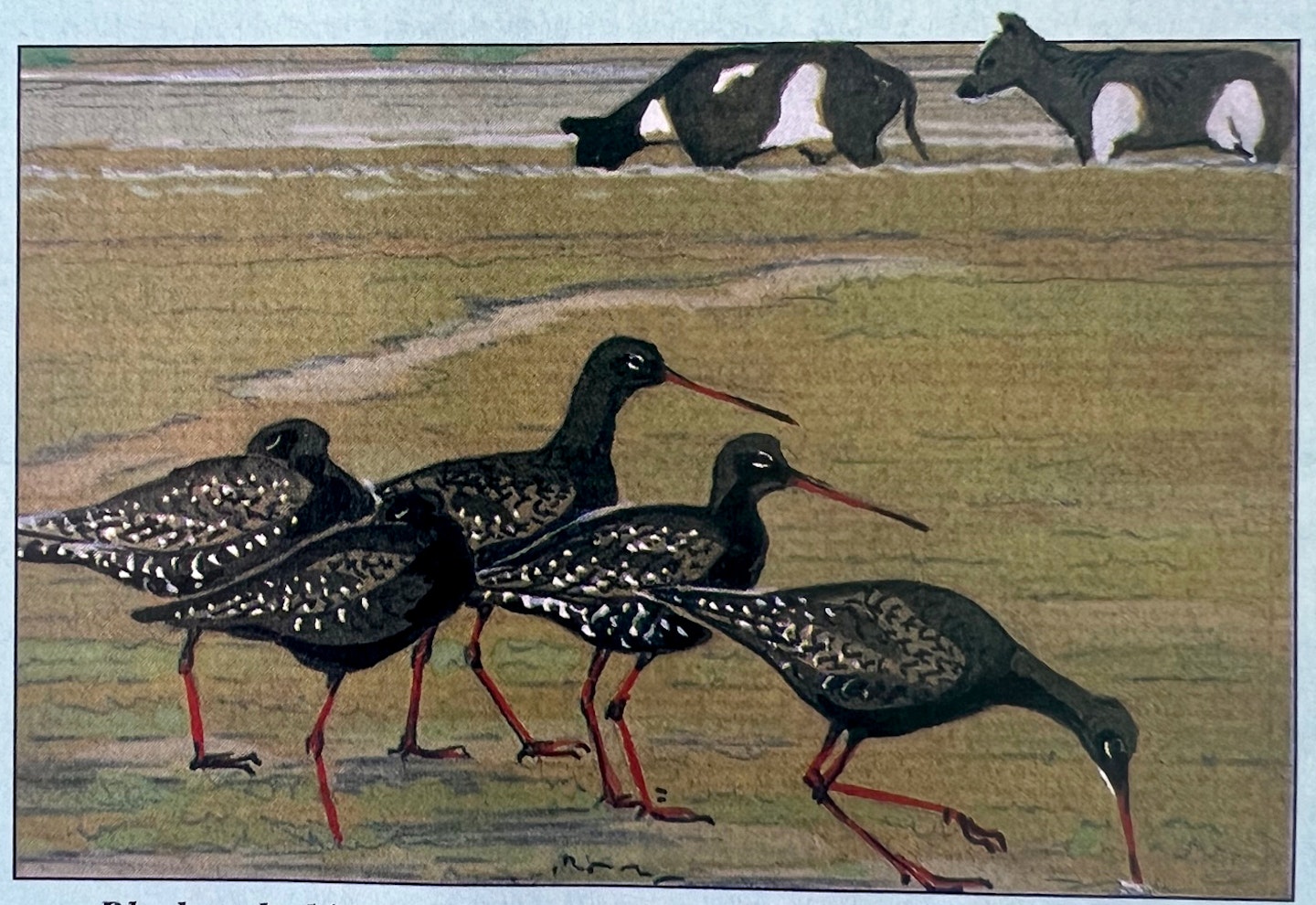

The spot that really intrigued me, however, was a meadow inside the Severn flood bank. In spite of its position, it did fill with water and being regularly grazed and soiled by cattle, an excellent little wetland ensured. My first visit to it in 1966 produced a small party of Spotted Redshanks wearing summer plumage, my first ‘black birds’ since Finland in 1957.

Not every later approach provided such thrills, but the meadow’s list grew to include Little and Temminck’s Stints, Little Gull and Scandinavian Rock Pipit. The hedges that led to it were splendidly old and ragged, catching several falls of night migrants. Two wandering Marsh Warblers were the best of those.

Even now, a quarter century later, the meadow still attracts good birds. With an excellent estuary and the majestic 100-acre wilderness only a few wingbeats away, they should have ignored it but surely they did not.

At Frocester and Eastcombe in the Cotswolds – five and 20 minutes east of Frampton – I was largely unsuccessful in finding a particular habitat focus on birds. The lack of visible water and the tumbled terrain provided no unusual catchment, even when I trod all the tetrads in the 10-kilometre square around East-combe. Fifteen years later, however, Terry James and some other Frampton friends found one above Brimscombe near Stroud – no less than a regular “pitstop” for chats and Ring Ouzels!

Once again, in Epping Forest, I did not expect that cathedral of trees to present concentrations of birds. Chingford Pond would always have something on it, but otherwise it was a “hard slog and cricked neck” routine. Then it dawned on me that the deer runnings – tussocky glades with birch clumps – and certain sectors near the forest edge always provided a fuller cross-section of the bird population than the thickets and canopy.

In the winter of 1971/72, a nine-mile sequence of winter counts proved that bird distribution within the forest was much more subtle than at first glance. Finally, an officially empty, but nevertheless fascinating, hunt for Short-toed Treecreepers confirmed that one break in the southernwoods was indeed a magic place. A walk along it would always produce interesting birds, notably Lesser Whitethroats, hundreds of metres from where they should have been.

There, one day, Stanley Cramp and I were overflown by a Golden Oriole and on another, I was trounced by a too-fast but undoubtedly ‘ungreat’ grey shrike. Even the late Peter Grant, taking a break from our discussions of stint identification, came under this spot’s spell and he was a self-confessed non-woodsman!

On to the East Riding (I still can’t write North Humberside with any pleasure!) where I first lived in Hessle, a village turned garden suburb by the spread of Hull. Casting about for walks for the kids, we were directed to ‘Little Switzerland’, a chalk quarry turned scrub wilderness. It clearly had magic properties for birds, providing migrant Redstarts every time, plus Willow Tits and wintering Woodcock but, alas, the construction of the north end of the Humber Bridge blew it away.

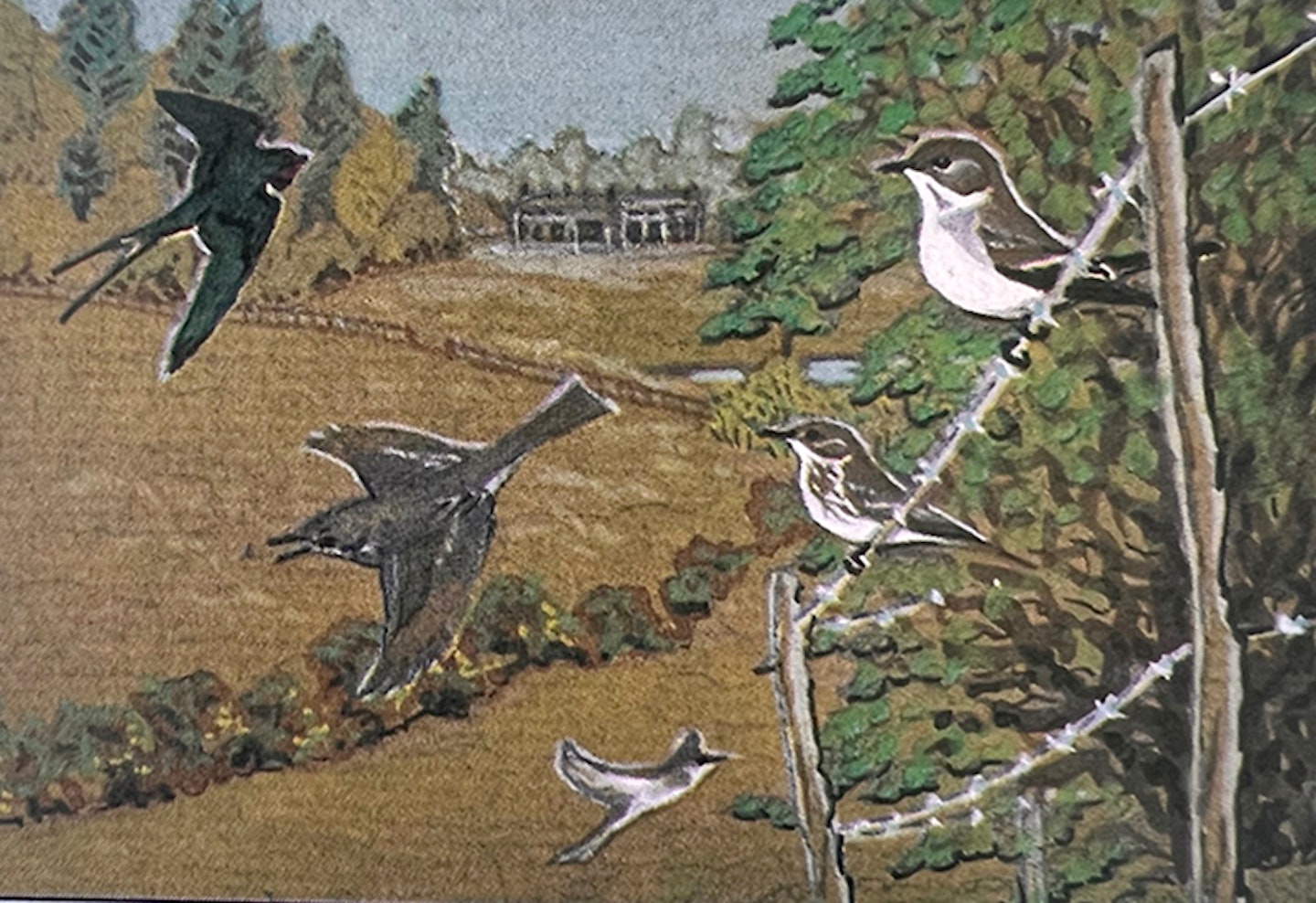

Moving 20 miles west to Holme upon Spalding Moor, I began an intensive study of cereal farmland and a wooded but failing estate. To my surprise, the big house’s fine trees and lake exerted little pull on birds, (contra my experiences in Regent’s Park), but little by little, I realised that two other areas did provide high strike rates.

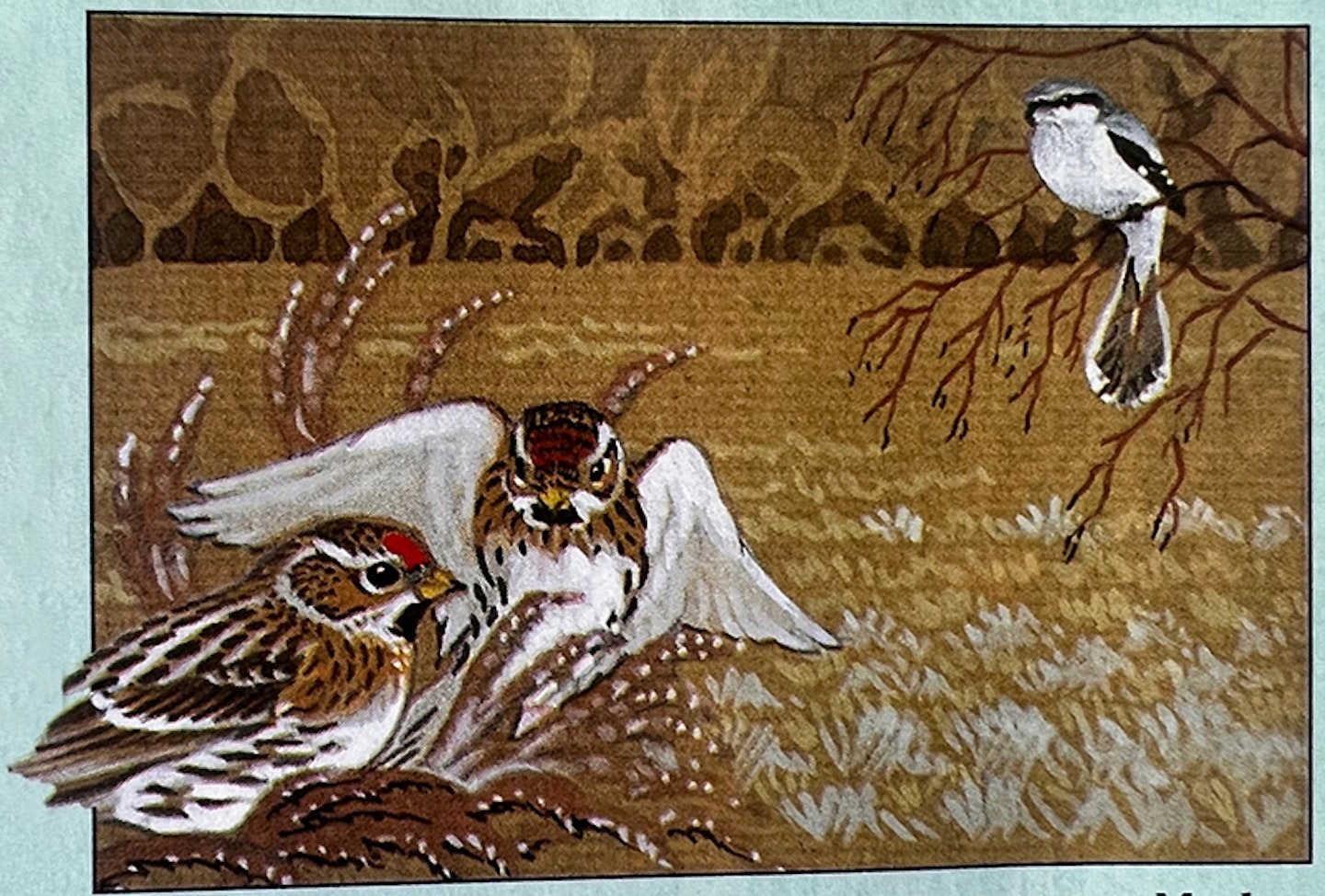

The first was a strip of white taiga (deciduous forest) consisting mainly of birches and small bogs. Its delivery of Fenno-Scandian species was uncanny. I mentioned some in my December 1989 article; others included more than 100 wintering Teal and shy Robins of the Continental race, a few taking up winter territories and singing even more sadly than my local birds.

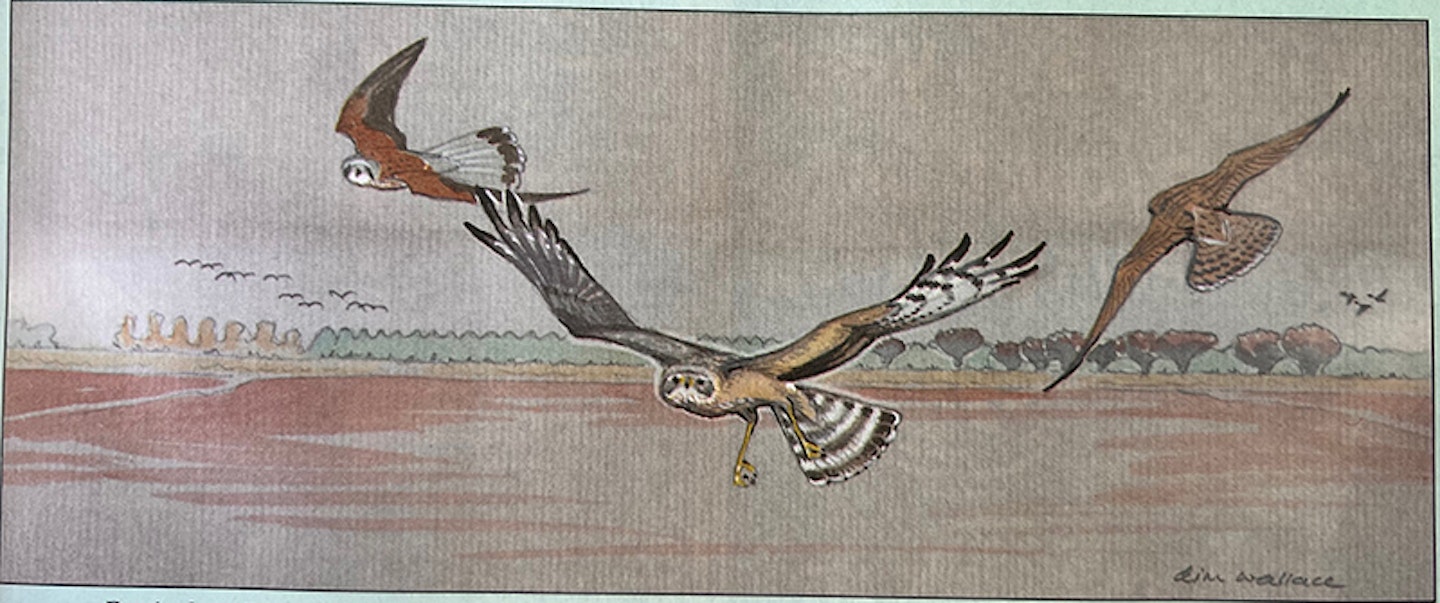

The second magic spot was exterminated by plough in 1988, but it had been a carr (in the open East Riding sense) for the previous 115 years. I enjoyed the last seven of these. Mostly damp tussock grass, it looked pretty barren, but by working its edge dykes (particularly where cows drank) and never ignoring a small pond surrounded by Hawthorns and the thistles that grew thicker after every year’s drain clearance, I saw some remarkable sights. In clear echoes of previous wilder centuries, the carr pulled in Bewick’s Swans, roving harriers (one very pale bird was a heart-stopper), Goshawks, Short-eared Owls, parties of Stonechats and hundreds of Goldfinches.

"Crossplains has given me more avian inland shocks than any other place. Yet I might well have ignored it completely..."

Once, in December 1983, late-moving thrushes poured down from the sky into the Hawthorns, strangely ignoring lush woods to the north. The fact that the little wilderness was lost to wildlife galls me very much. Last summer, I went to check its productivity of cereals and found unevenly grown and partly discoloured plants, partly flooded and full of stubborn Juncus (sedge). Why did the farmer bother? Am I paying the grain storage cost via EC subsidy?

Moving to East Staffordshire, and almost as far from the sea as possible in England, I was still unsure of discovering other local foci on birds. Initially, I tried hard to make a magic spot out of Hollybush Lake near Newborough. Set in parkland and with an excellent willow and Sycamore wood below the dam, it should have been one, but interesting stars like Pied Flycatcher and pale redpolls have somehow not built into a really impressive list, while problems with close access – Pheasants come before villagers and birdwatchers in Meynell Hunt country! – have now reduced my chances anyway.

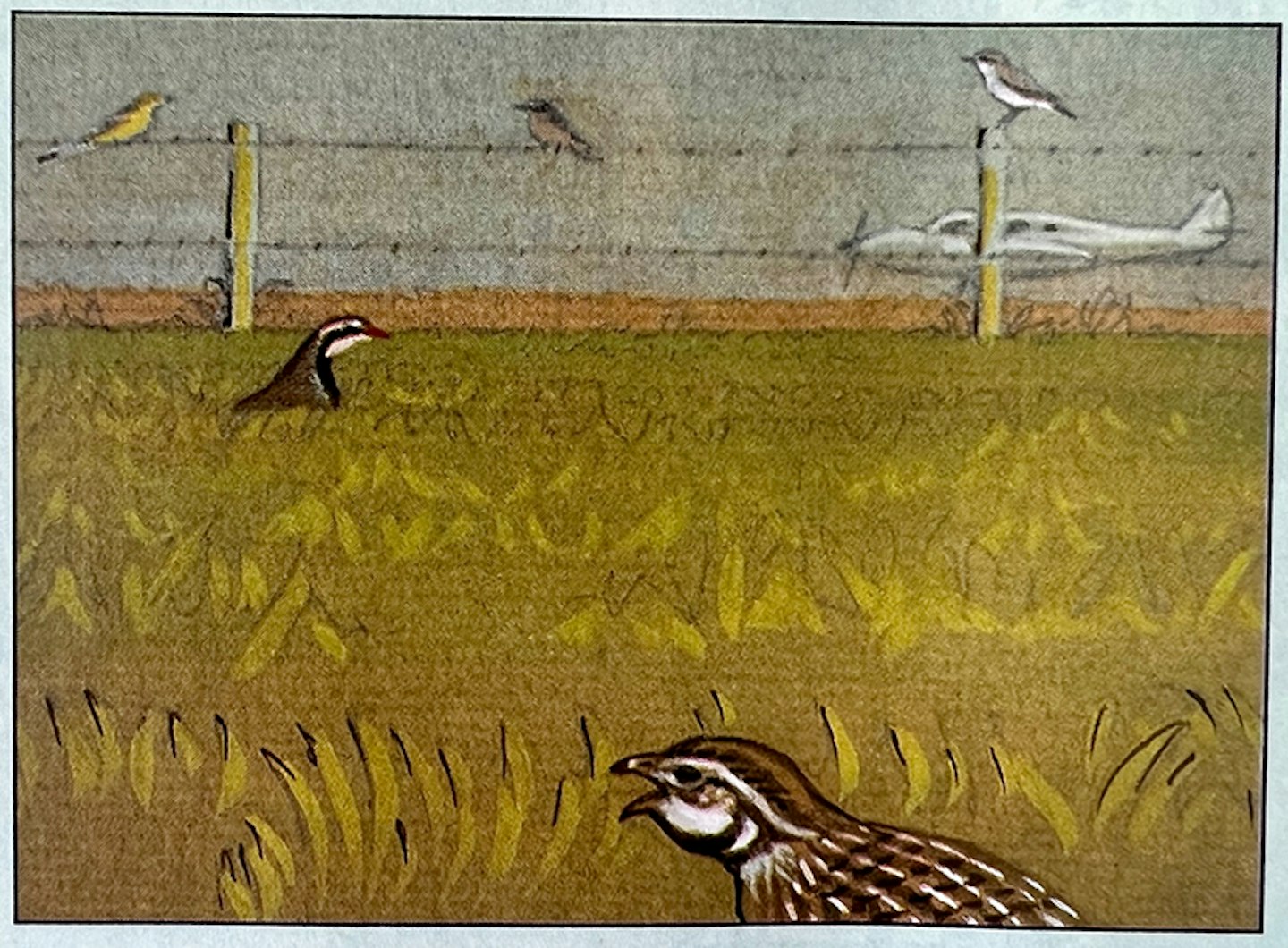

As Hollybush was withered (ornithologically), a much less attractive and much more artificial place has blossomed, astonishingly. Looking at Crossplains (old name) or Needwood Airport from the road and you see wire fences, cow grass, wheat or barley. Explore it closely, and you find in addition rotting, fly-breeding stacks of soiled bedding, broken runway edges with a steppe-like flora, emergent scrub, two ponds, one unploughable patch of wet grass, two excellent wood edges and some thick ledges. You feel as if you are visiting an upland plateau.

My first visit was highlit by a vagrant Little Ringed Plover and a friendly farmer commented that one pond held duck in the winter. I sensed that a seemingly empty place might repay regular observation. Courtesy of two farmers and a slightly mystified group of light plane pilots, I got permission to use my car as a mobile hide along the runways and the perimeter tracks.

The effect of thrashing Crossplains (metaphorically) has been astonishing. The records of uncommon, “Why on earth should they be here?” birds have kept on growing. No data in the Birds of the West Midlands (the excellent local avifauna) trailed the airport’s three species of geese, seven of duck, six of diurnal raptors – Goshawk, Merlin and Peregrine now annual – Quail, 14 kinds of waders – Ruff regular among the Lapwings – seven of gulls, Water and Rock Pipits, ordinary, hybrid and ‘mutant’ Yellow and Blue-headed Wagtails, thousands of winter thrushes, odd Waxwing, regular Twite and, as related in the November issue, Lapland Buntings among the Sky Larks every October!

Much as I was enthralled by the oasis effect of London’s parks in the 1950s and 1960s, this has now been overtaken by a real addiction to decaying airports. Crossplains has given me more avian inland shocks than any other place. Yet I might well have ignored it completely, and the only other natural historian who visits it comes to monitor the population of a tiny black fly. How many other disused airports are waiting to have their good birds discovered?

Just why certain necks of woods, parts of fields, quiet waters and amazingly broken runways exercise peculiarly strong attractions to birds, I am not sure. Undoubtedly, birds see benefits in habitat niches that even the most skilled human observers habitat reliefs and contrasts, e.g. a glint of water on a dark night, wood edges, “island” thickets differing tree colours;

-

Leading lines, e.g. hedges and canopy breaks or even apparently insignificant features such as the strips of grass, tussocks and brambles under wire fences;

-

Lees (shelters from wind) e.g. not just behind trees, even in field folds;

-

Sun angles, particularly when such enhance lees by bringing out insects (e.g. east facing hedges at dawn);

-

Diverse vegetation, hence several food sources, e.g. seeds and insects from natural ponds or wind-blown concentrations;

-

Safe roosts, e.g. not just woods and large waters but also island thickets and field centres;

-

And their compound benefit to birds has to be enhanced survival.

The thrills in finding unusually diverse bird presences in seemingly standard countryside are considerable, giving you also the chance to harvest local records much more efficiently than by constant cross-section.

The birds may never rate relay on any Birdline but as records supporting BTO surveys and county research, they can add to the conservation database still sorely needed if our favourite beings are to be protected, wherever they live.