December 1990

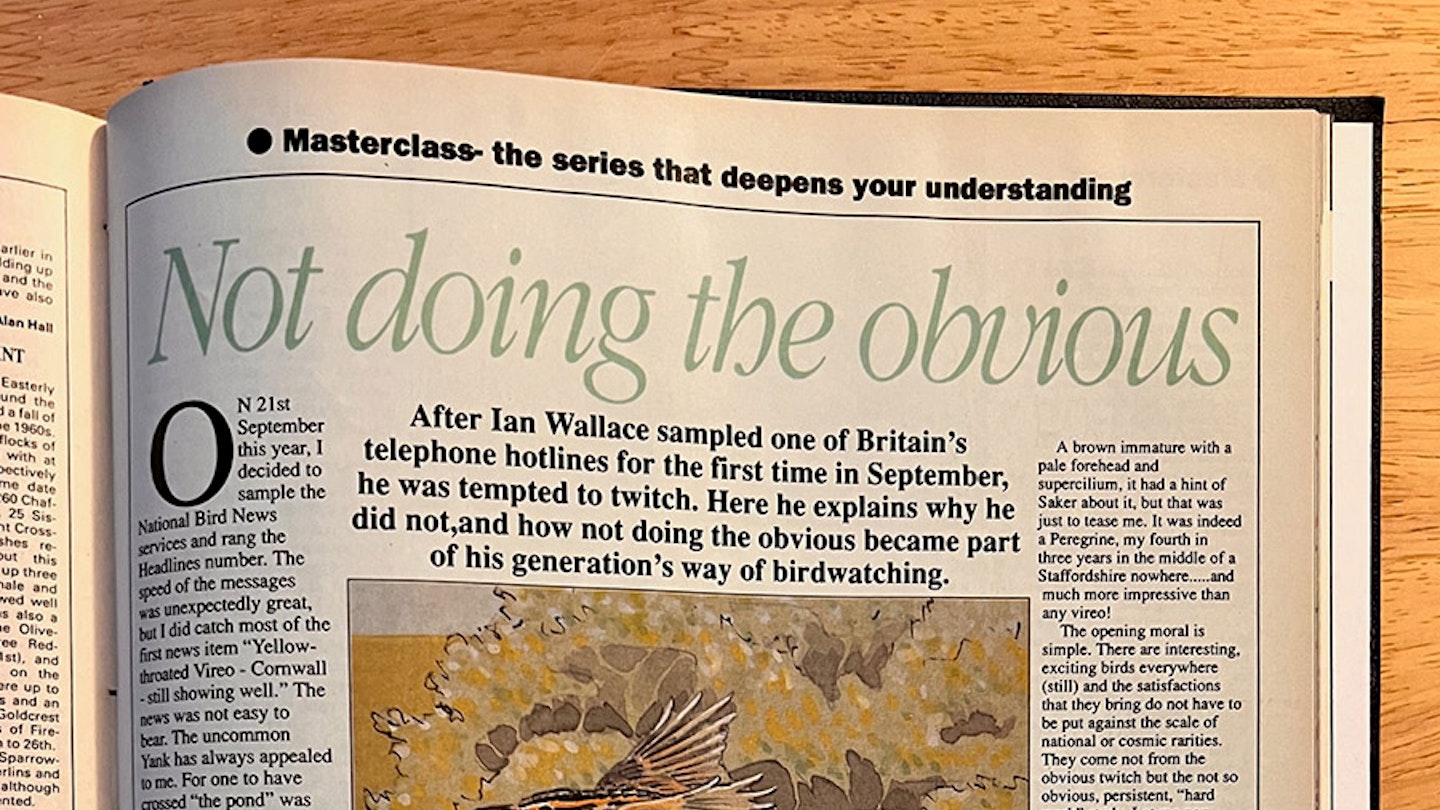

Not doing the obvious

After Ian Wallace sampled one of Britain’s telephone hotlines for the first time in September, he was tempted to twitch. Here he explains why he did not, and how not doing the obvious became part of his generation’s way of birdwatching.

On 21 September this year [1990], I decided to sample the National Bird News services and rang the Headlines number. The speed of the messages was unexpectedly great, but I did catch most of the first news item “Yellow-throated Vireo – Cornwall – still showing well.” The news was not easy to bear. The uncommon Yank has always appealed to me. For one to have crossed “the pond” was almost a miracle.

The “obvious” salve to my perplexed state was to pump at least £55 into the car (no thanks, Saddam), pile down the M5 and A30 and pray for the dawn of September 22 to deliver a Yank lifer.

The “not so obvious” somewhat-Scottish antidote was not to invest money and time in a mass twitch, but to grit my teeth and work my local patch even harder. There, since 13 September, a dusty, birdless late summer had become a cleaner, wetter, bird-full autumn.

Already I had been delighted by my area’s first two Grey Plovers; disturbed by two seemingly-hybrid Golden x American Golden Plovers; flown past by a Goshawk; intrigued by pinkish or buff Meadow Pipits (from ancient Lusitania) and totally slain by the most aggressive of the 40 Pied Wagtails normally seen on the partly disused airfield, where I watch regularly, chasing off an apparent immature Citrine from ‘their’ manure-strewn stubble.

So, it was not too difficult to avoid the obvious and stay at home. Overnight it rained continuously.

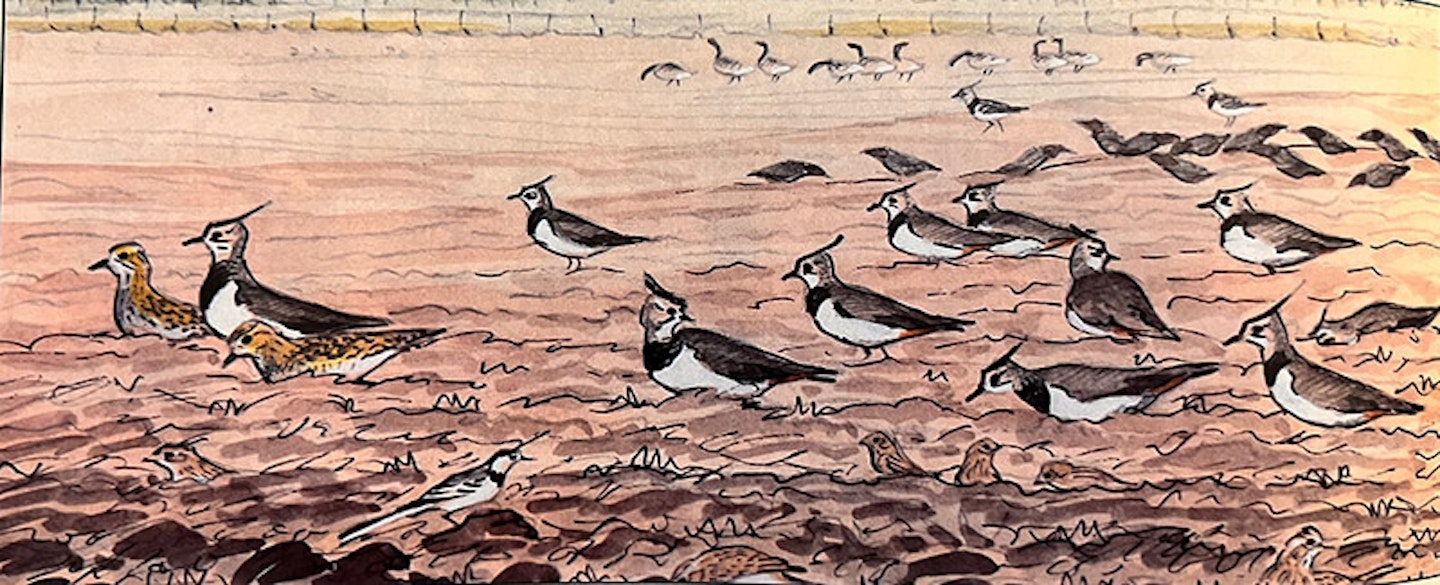

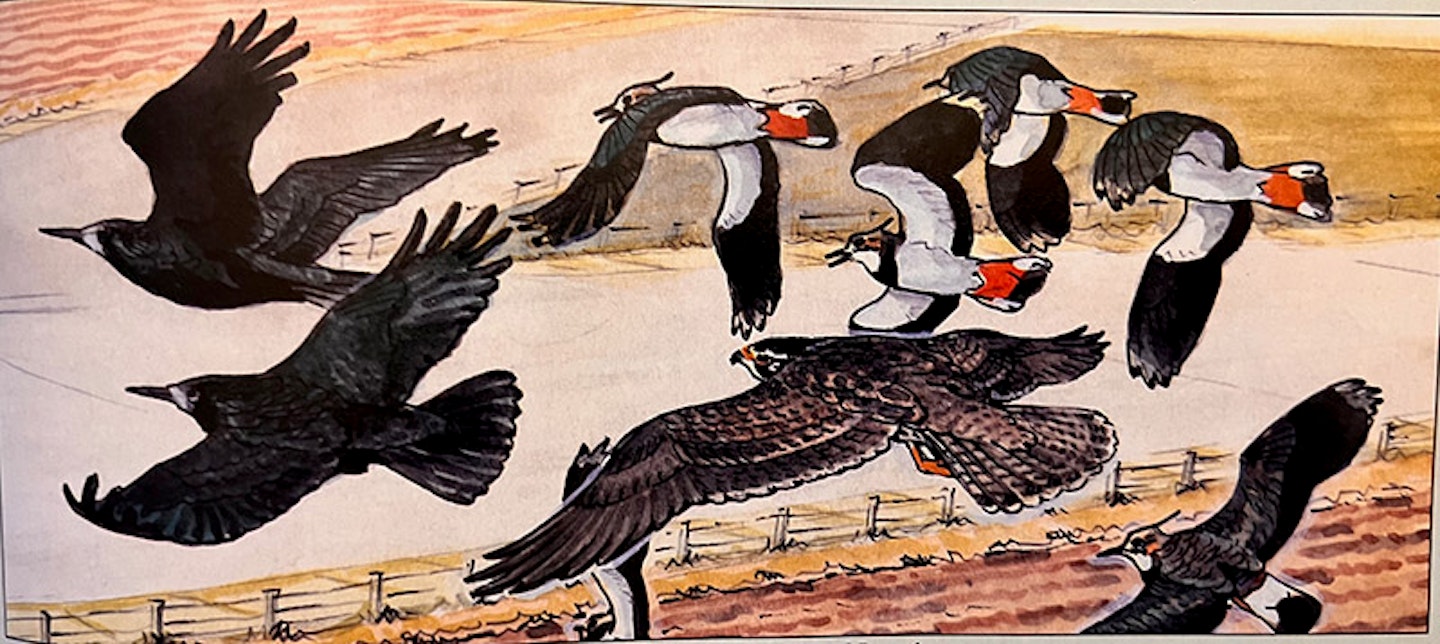

As the weather cleared on the 22nd, I got to the airport fields just in time to see every plover, lark, pipit and finch on them get up and go like hell. All around the horizon, too, birds were panicking. There had to be a really savage raptor somewhere.

At 0820, it appeared to make a pass at some tardy Lapwings and Rooks. At 600 yards, it looked like a falcon [female] Peregrine but I was not sure.

I stayed on for the other birds to return, notching my third Ruff of the autumn and my third Twite of the year, but most remained shy. At 0855, larks began to fly away again – this time low without a call – and two minutes later the hulk reappeared to land on a manure clod and to preen only 150 yards from my car.

A brown immature with a pale forehead and supercilium, it had a hint of Saker about it, but that was just to tease me. It was indeed a Peregrine, my fourth in three years in the middle of a Staffordshire nowhere… and much more impressive than any vireo!

The opening moral is simple. There are interesting, exciting birds everywhere (still) and the satisfactions that they bring do not have to be put against the scale of national or cosmic rarities. They come not from the obvious twitch but the not so obvious, persistent, “hard work” study. Let me now recall some other events and personalities of earlier years that have provoked the latter form of birdwatching.

In the late 1940s and early 1950, most of my holiday birdwatching was done around London, train and foot-slogging from Waterloo to the Staines reservoirs and one of the all time great sewage farms at Perry Oaks.

I even collected the bonus of a flying saucer over Heathrow Airport (independently corroborated, so don’t knock it!). Somehow, however, it only added up to a second-best performance, with “trained soldiers’ like C.A. (Cliff) White always first to the uncommon birds. There had to be a better way to some personal achievement.

I found it in Inner London’s green spaces of Regent’s Park and on top of nearby Primrose Hill. The 700-odd acres already had regular watchers: Professor E. H. Warmington, complete with the title of Royal Parks Official Observer (and thus to me of awesome stature), and W. E. (Bunny) Teagle, full of boundless enthusiasm, but only I lived “just down the road” in Marylebone High Street.

It came to me, that if I really worked hard, I could make the park’s birds my own. A selfish goal maybe, but it fuelled a 15 year association with Regent’s Park and Inner London. Effectively I worked the area in the classic observatory manner, surveying the breeding population and sampling migrant and wintering birds.

As I have related earlier, I missed the park’s one super rarity but my observations did slowly assemble into results significant enough to be published annually in the London Bird Report and occasionally in Bird Migration and British Birds. Importantly, my unusual behaviour attracted attention from other studious observers, notably Stanley Cramp (then still working for the Customs and Excise, but already causing change in many ornithological camps, particularly in the fight against persistent toxic chemicals).

Drawing on full-strength, no-tip Players cigarettes almost continually, Stanley had the unnerving habit of knowing what extra work young observers could and should do and making sure that they actually did it. None of us who served under him in the Ornithological Section of the London Natural History Society will ever forget his example.

Stanley’s final, rather stern image – conservation warrior and Chief Editor of Birds of the Western Palearctic – has masked his real person or ghost, happily returned (I fancy), to counting Blackbirds in London’s Squares. Only those of us who worked close to him know how Stanley held together BB’s nerves – when its circulation went below 3,000 forcing Witherbys to sell their founder’s favourite creation to MacMillan – by sheer will and boundless good humour and faith.

Did Stanley Cramp ever do the obvious and chase rarities? Abroad, quite a lot; at home, not often... but I well remember how flanked by his favourite LNHS lieutenants (Bill Park and Raymond Cordero), he managed to give up his Players long enough to see his first Aquatic Warbler at Dungeness.

His smile was as long and genuine as the bird’s supercilium. It was the only proof that I ever needed to know that Stanley was far softer inside than the ‘Goshawk’ tag put on him (by his eulogist in BB) implied.

During the 1950s and 1960s, my peers were interested mainly in migration, romantic places in the Far North and the occasional new bird. You will have gathered that then, as now, Fair Isle afforded all those aspects and if we envied anyone, it was the warden of its bird observatory. This position was held first by Ken Williamson and second by Peter Davis. News of their annual exploits and captures filtered south to light up our winters (no instant news then!) and many of us wanted to be them.

How could they ever give up the place and its magic birds? Ornithological man does not live on the avian equivalent of cream teas alone, however, and Shetland’s winters are long, dark and raw. So, both Ken and Peter changed tack, each of them in turn first becoming the BTO’s migration expert (in the brief period that migration studies were funded), and second forsaking that role (when the budget was cut) and adapting to the early tasks of conservation.

Thus Ken lost his title of “King of Drift and Rare Birds” and became “First Disciple of the Common Birds Census”, retaining overtly only his early taxonomic enthusiasms as shown in the BTO’s three Ringers’ Guides. Peter ended up in central Wales, bringing his penetrative intelligence to the preservation of raised bogs and Red Kites – and Polecats!

Our eyebrows went up in the face of such undreamt-of metamorphoses but their message was the same. The not so obvious in birds and birdwatching had captured our heroes and should perhaps compel us, too. Accordingly, there broke out in many birdwatching circles, arguments about the merits of common/breeding and uncommon/migrant or rare birds. In a BBC debate, the motion that only studies on common birds had lasting worth was carried. I could not believe my ears.

The slow, discomforting conversion of many of us to a broader and more complex form of birdwatching came quickly in the 1960s.

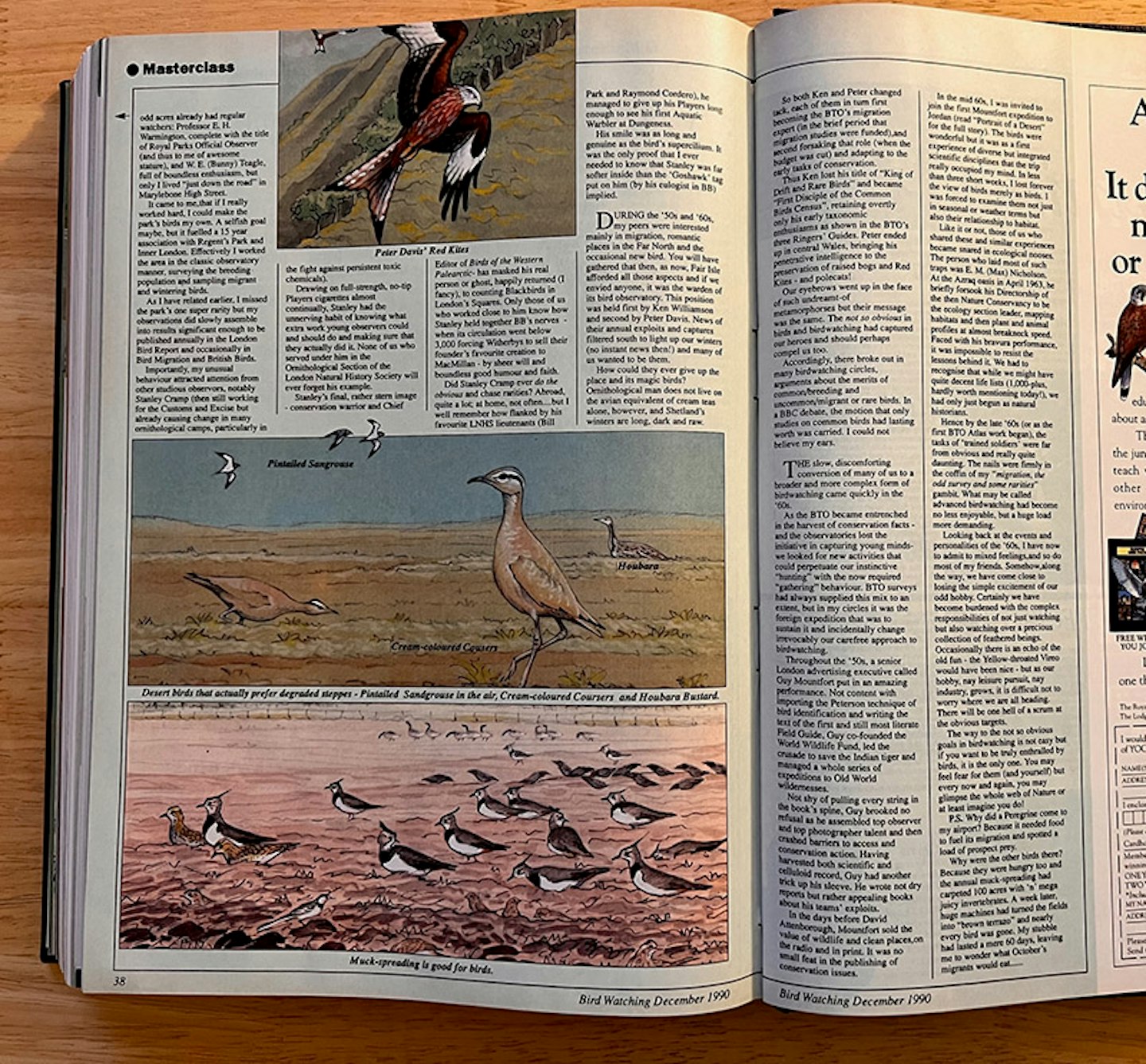

As the BTO became entrenched in the harvest of conservation facts – and the observatories lost the initiative in capturing young minds-we looked for new activities that could perpetuate our instinctive “hunting” with the now required “gathering” behaviour. BTO surveys had always supplied this mix to an extent, but in my circles it was the foreign expedition that was to sustain it and incidentally change irrevocably our carefree approach to birdwatching.

Throughout the 1950s, a senior London advertising executive called Guy Mountfort put in an amazing performance. Not content with importing the Peterson technique of bird identification and writing the text of the first and still most literate [in 1990] Field Guide, Guy co-founded the World Wildlife Fund, led the crusade to save the Indian Tiger and managed a whole series of expeditions to Old World wildernesses.

Not shy of pulling every string in the book’s spine, Guy brooked no refusal as he assembled top observer and top photographer talent and then crashed barriers to access and conservation action. Having harvested both scientific and celluloid record, Guy had another trick up his sleeve. He wrote not dry reports but rather appealing books about his teams’ exploits.

In the days before David Attenborough, Mountfort sold the value of wildlife and clean places, on the radio and in print. It was no small feat in the publishing of conservation issues

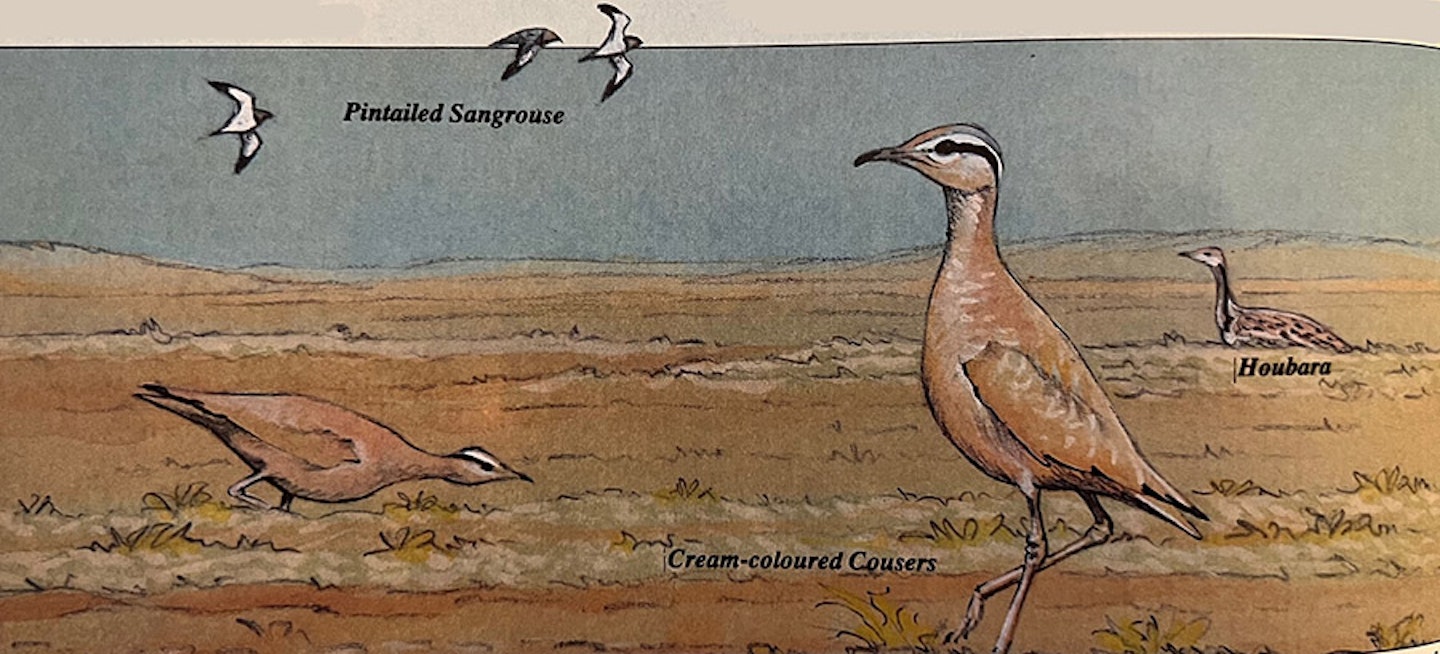

In the mid 60s, I was invited to join the first Mountfort expedition to Jordan (read “Portrait of a Desert” for the full story). The birds were wonderful but it was as a first experience of diverse but integrated scientific disciplines that the trip really occupied my mind. In less than three short weeks, I lost forever the view of birds merely as birds. I was forced to examine them not just in seasonal or weather terms but also their relationship to habitat. Like it or not, those of us who shared these and similar experiences became snared in ecological nooses.

The person who laid most of such traps was E. M. (Max) Nicholson. At the Azraq oasis in April 1963, he briefly forsook his Directorship of the then Nature Conservancy to be the ecology section leader, mapping habitats and then plant and animal profiles at almost breakneck speed. Faced with his bravura performance, it was impossible to resist the lessons behind it. We had to recognise that while we might have quite decent life lists (1,000-plus, hardly worth mentioning today!), we had only just begun as natural historians.

Hence by the late 1960s (or as the first BTO Atlas work began), the tasks of ‘trained soldiers’ were far from obvious and really quite daunting. The nails were firmly in the coffin of my “migration, the odd survey and some rarities” gambit. What may be called advanced birdwatching had become no less enjoyable, but a huge load more demanding.

Looking back at the events and personalities of the 1960s, I have now to admit to mixed feelings, and so do most of my friends. Somehow, along the way, we have come close to losing the simple excitement of our odd hobby. Certainly, we have become burdened with the complex responsibilities of not just watching but also watching over a precious collection of feathered beings

Occasionally, there is an echo of the old fun – the Yellow-throated Vireo would have been nice – but as our hobby, nay leisure pursuit, nay industry, grows, it is difficult not to worry where we are all heading. There will be one hell of a scrum at the obvious targets. The way to the not so obvious goals in birdwatching is not easy but if you want to be truly enthralled by birds, it is the only one. You may feel fear for them (and yourself) but every now and again, you may glimpse the whole web of Nature, or at least imagine you do!

P.S. Why did a Peregrine come to my airport? Because it needed food to fuel its migration and spotted a load of prospect prey.

Why were the other birds there? Because they were hungry, too, and the annual muck-spreading had carpeted 100 acres with ‘n’ mega juicy invertebrates. A week later, huge machines had turned the fields into “brown terrazo” and nearly every bird was gone. My stubble had lasted a mere 60 days, leaving me to wonder what October’s migrants would eat.