November 1990

Stealthy strategies

Recalling experiences developed over four decades of active birdwatching Ian Wallace highlights two tactics that may uncover interesting birds out of season or hidden among commoner brethren.

Looking for fellow travellers

Towards the end of last month’s article mentioned that occasionally among lots of common Golden Plovers, a rare Lesser Golden, or as we must now say American or Pacific Golden Plover – shows.

The odds are that the rarity joins with the common birds because it has lows its way, feels out of place and lonely, and therefore seeks out the closest company to its own kind. Thereby it feels less lost and, importantly, can benefit from its companions superior local knowledge of flyways and food sources.

I have found Lessers doing this twice in Silly and at four localities inside the cast coast in the last 28 years.

My mental shorthand for this kind of behaviour is ‘fellow travelling’ and it is worth investigation during the two migration seasons, through the winter and – in gregarious species – at almost any time.

Historically, the classic carrier species or tribe are the common geese. The person who taught us most about their fellow travellers was the late and sadly missed Sir Peter Scott. I have related already how much his early books meant to me in my formative years. In October 1952, on my pre-Mau Mau leave from the Army, I finally got to meet the great man.

Dad had been instrumental in providing for Slimbridge’s fish-eating ducks a supply of young trout and his efforts were rewarded by a whole family invitation to the New Grounds. So, we were privileged to have Sir Peter as our guide to the first geese of that winter – they came much earlier in the climate of 40 years ago – and I was entranced by his tales of what was then the best fellow traveller of all.: the odd immaculate Lesser Whitefront nibbling quickly and sporting long wingtips among the Russian Whitefronts.

The discovery of Britain’s third only Lesser Whitefront on the Dumbles in 1945 was one of the main springs to the foundation of the Wildfowl and Wetlands Trust at Slimbridge.

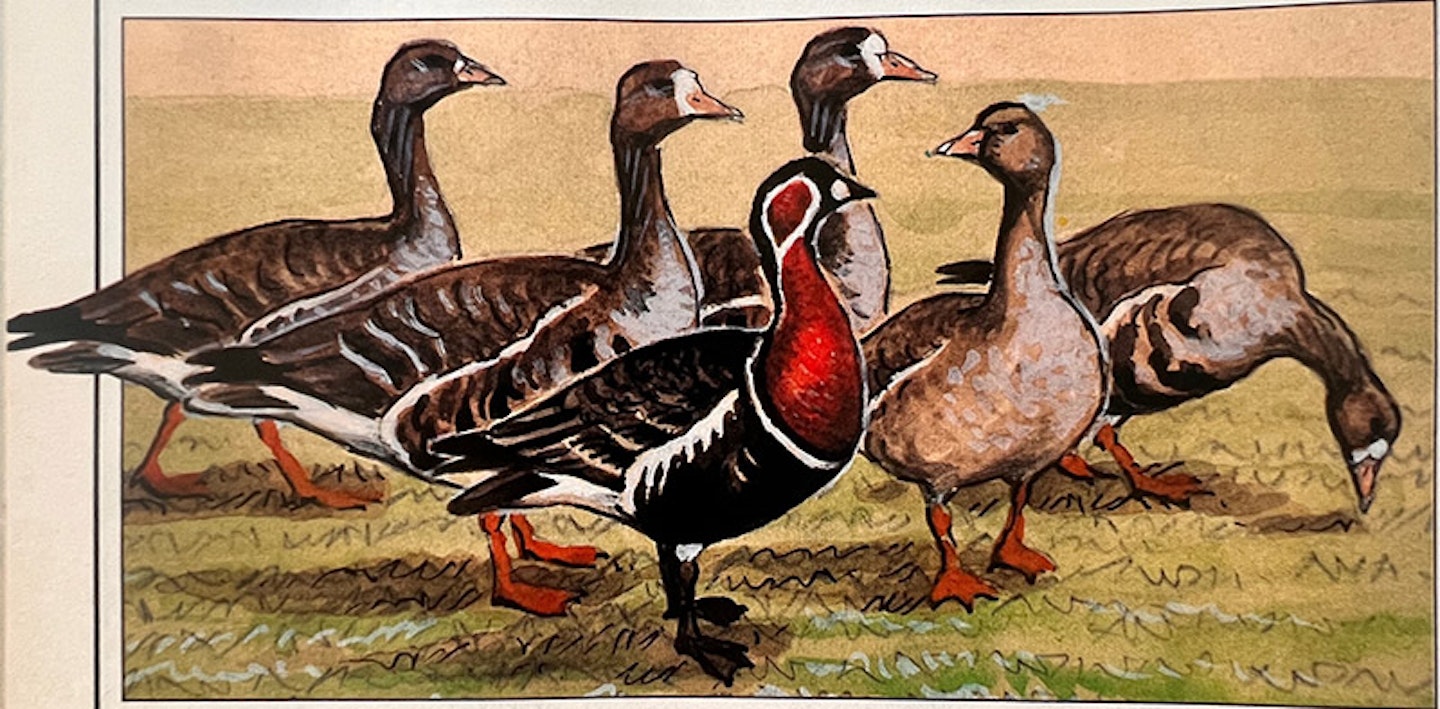

On our 1952 visit, we had to make do with some Pinkfeet and two Peregrines for excitement, but between 1965 and 1968 I lived only 20 minutes from the Russian flock and had the often cold, but nevertheless huge pleasures of several self-found Lessers and one heart-stopping Red-breasted Goose. It took me nearly 15 years, but eventually I felt that I had got close to Sir Peter’s skill in spotting fellow travellers.

In 1975, I discussed the potential of ‘fellow travelling’ with another artist called Peter, this time surnamed Hayman. Ever the enthusiast for neglected studies, Peter’s eyes sparkled as we mused on what a mass winter search of Sky Larks would produce. We coined the term ‘carrier species’ for a common species that was prone to pick up ‘fellow travellers’. We resolved that one day we would join forces and test our theory.

" Even if you are a beginner and unsure of some identifications, you can build greater skills and knowledge by using carrier species as key learning tasks . . . ."

Alas, Peter Hayman and I have never got our act together but there is plenty of evidence that uncommon and rare birds are carried by closely-related common species.

In my current study of farmland birds in Staffordshire, the Sky Lark is far from common. So cleaned is the land that the herald of spring is truly scarce and necessarily nomadic. Only in the now brief period of autumn stubble does it form the flocks that my generation once took for granted.

Even so, my parties of Sky Larks are always worth a close watch or gentle ‘turnover’. In the last five years they have carried or attracted four species of pipit, almost annual Lapland Buntings, occasional Snow Buntings and – one splendid October day – a Short-toed Lark. All these species share with the common lark the need for open, seeded or invertebrate-rich earth.

The most striking tribe of fellow travellers are the Eurasian thrushes. Of the 90 odd individuals of five vagrant species recorded to date, at least 25 have been found inland in company with other wintering thrushes. How many more would we find if we searched through every thrush flock carefully?

Other carrier species and families are Wigeon (for American), diving ducks (for Ring-necked), Eiders (for King), Scoters (for Surf), Little Stints (for other stints), common gulls (for all the others), Swifts (for southern cousins, especially in late May passages), north-eastern Meadow Pipits (for Red-throated), autumn Sedge Warblers (for Aquatic), Starlings (for Rose-coloured), Mealy Redpolls (for Arctic), irrupting Crossbills (for Two-barred), and Yellowhammers (for Pine Bunting).

This is an incomplete but nevertheless mouth-watering list of quite possible discoveries and I want to stress that it is not temporarily restricted to May, September and October. Of my seven fellow travellers in the 13 chances just noted, six have been dated in ‘ordinary’ months.

Note also that carrier species like gulls, Swifts and Starlings can be found almost anywhere within our lands. It makes sense to search through any concentration and not restrict such observation to coasts or well known hotspots.

Even if you are a beginner and unsure of some identifications, you can build greater skills and knowledge by using carrier species as key learning tasks and going on to spot the odd bird among them.

Here are some more target associations: Garganey and Teal, Ferruginous Ducks and Tufteds, Hobby and hirundines (illustrated last month). Whinchat and Wheatear, Pied among Spotted Flycatchers, Cirl Bunting with Yellowhammer (a second reason to search the latter’s flocks!), and Brambling and Chaffinch.

Let me repeat that these pairs of fellow travellers are widely visible throughout Britain. Looking for them near your home will be profitable, I promise.

Staying with it

In the late 1940s and 1950s, we were less educated in the best times for big days (those which offer most chances of diverse bird species). In turn we were far less prone to the fevers promoted these days by the migrant and rarity seasons. A projected trip to an observatory would produce a scan of the Handbook and a rough assessment of likely good fortune. I cannot remember, however, producing a full workout of the major passage periods of rarity dates until 1962.

In that year, I made my first spring visit to St Agnes with the sharp purpose of being there on May 3, by the few past records the likely date of another Subalpine Warbler. Death to statistics, the day passed empty of any such bird, but on the 9th, a spring fog cleared to display a Tawny Pipit and a Serin, both in song!

Nearly three decades later, all twitchers and many other observers are steeped in the best dates and places for uncommon birds. The still growing hype of the rarity-bearing months is

staggering. It is a certain bet that we are still increasing the bias in avian records that are due to observer behaviour.

Is there an antidote to doing the obvious and obscuring further the true patterns of migration and vagrancy? Let me coax you into an affirmative answer. In the middle years of St Agnes magic, Bob Emmett, Karin and I decided to watch late autumn passage and time our visits to run into apparently barren November.

In 1967, we did not arrive until October 26. For five almost impossible days we were nearly blown back east to Penzance or south to France. After heavy lash from a southerly gale overnight on the 31st, we staggered out to Horse Point to see if those conditions and sea mist would bring in any seabirds.

"Study may seem a boring prospect, but persistent searches among common birds do pay off."

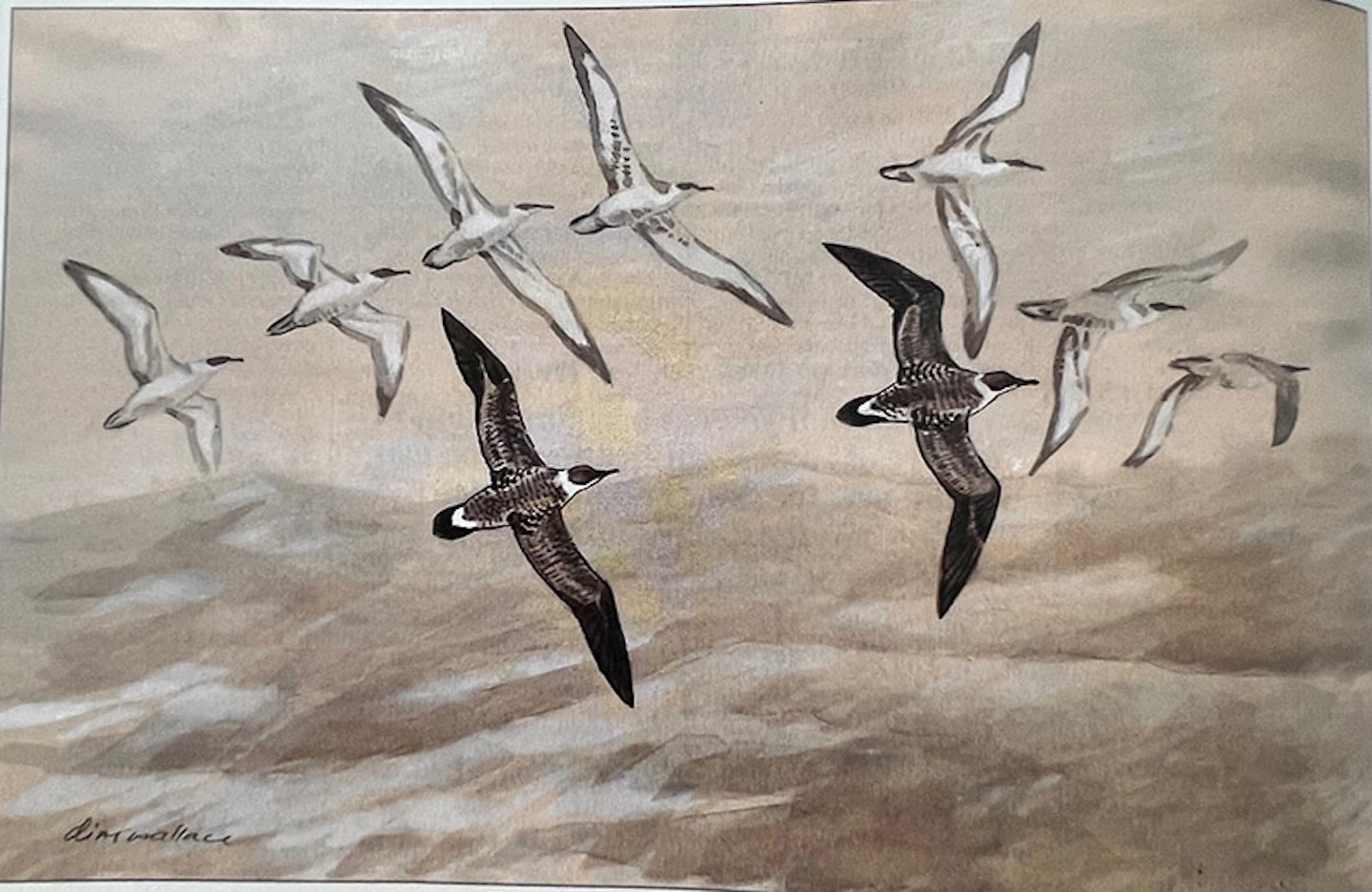

Within seconds of eye focus (or was it binocular drying), at 0900 hours we became aware of large, non-Fulmar tubenoses thundering past at over five birds per minute! Mostly Great Shearwaters – some coming in as close as the surf line – the birds passed continuously until 1030 hours. A second watch, began at noon, showed that they were still on the move at seven birds per minute.

Then, at 1225 hours, the sun broke through fully and they sheared away south and were gone. We identified only 342 of the 648 seen or glimpsed, but the likely total passage of no fewer than 1,950 birds (325 minutes x six birds) was then unprecedented. How many more thousands were milling south of Scilly, we could not guess.

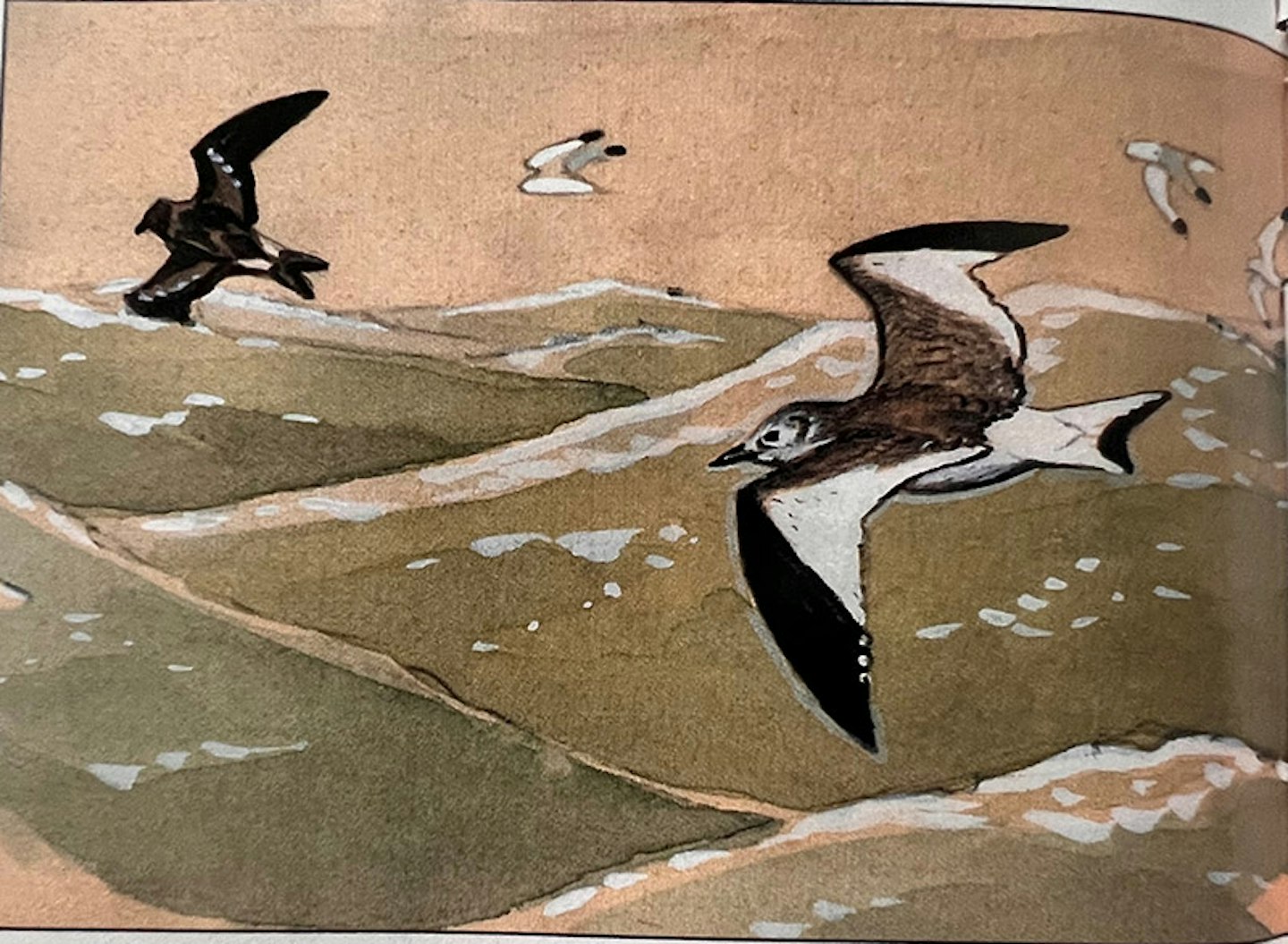

The next day, the gale swung back to the north. In the place of the large tubenoses, there was only a “beautiful small white shearwater (definitely not a Fulmar)” and “a superb Little Auk in full breeding plumage”, which just happened to be Bob’s second and my first. As the observatory log noted that night: “So once again, unremitting hard labour proves its worth. Despite the hellish weather, St Agnes gave forth yet more. All hail, lass!”

The lessons of 1 and 2 November 1967 became linked with my earlier convictions that late migration regularly occurs in November and even December. Hence my marked tendency to ‘stay with it’ all year and never hang up my boots in the observance of the older time rituals of birdwatching.

This behaviour is not a personal trait. Through the persistence particularly of ornithological study groups it has paid off handsomely for many other ‘trained soldiers’. In the modern records, seemingly out-of-season phenomena have steadily multiplied. The January peak of Surf Scoters from America, the seven month presence of Long-tailed Skuas in British and Irish waters, and the occasional wintering of other pelagic species that ought to be off South Africa are all excellent examples of the scientific proceeds of ‘staying with it’.

As I wrote in my piece on ‘working a patch’, regular study may seem a boring prospect, but persistent searches among common birds and out of traditional seasons do pay off. Mentioned above was my first Little Auk in the shape of a wind-blown waif. Let me end by eclipsing it totally by noting the occasional passages (not wrecks) of twinkling thousands now proved to occur off Flamborough Head. The FOGgies stayed with it and so added to our national ornithology. Well done!