October 1990

The virtues of patience

Drawing on years of practical experience, Ian Wallace recommends plenty of reading, and a reflective wait and see attitude out in the field to reap more rewards from your bird watching.

In the last three months, I have first recalled some past birdwatching traumas and second dispersed them (I hope) by reprising those influences that most helped in my early days.

I have one other ill to discuss, but I shall leave it to the end of this series. For the next six months, it is back to the coalface of field ornithology for more memories of its practice in past decades.

Finding crucial references

The classic books, and the foremost journal of the postwar quarter-century formed the ‘lingua franca’ of my generation and some of us knew much of them almost by heart.

Once in 1952, at 17 India Street – a Georgian townhouse that was the winter roost of the Fair Isle Bird Observatory in Edinburgh and the place of many ornithological gatherings – Ken Williamson put us on test. “Who knows his handbook?” he asked and then read out the pre-1940 dates of rare vagrants. We were mostly beaten but I managed to pick out a June 1894 record for Subalpine Warbler. Flushed with this small success, I resolved to read the literature with wider attention and more care.

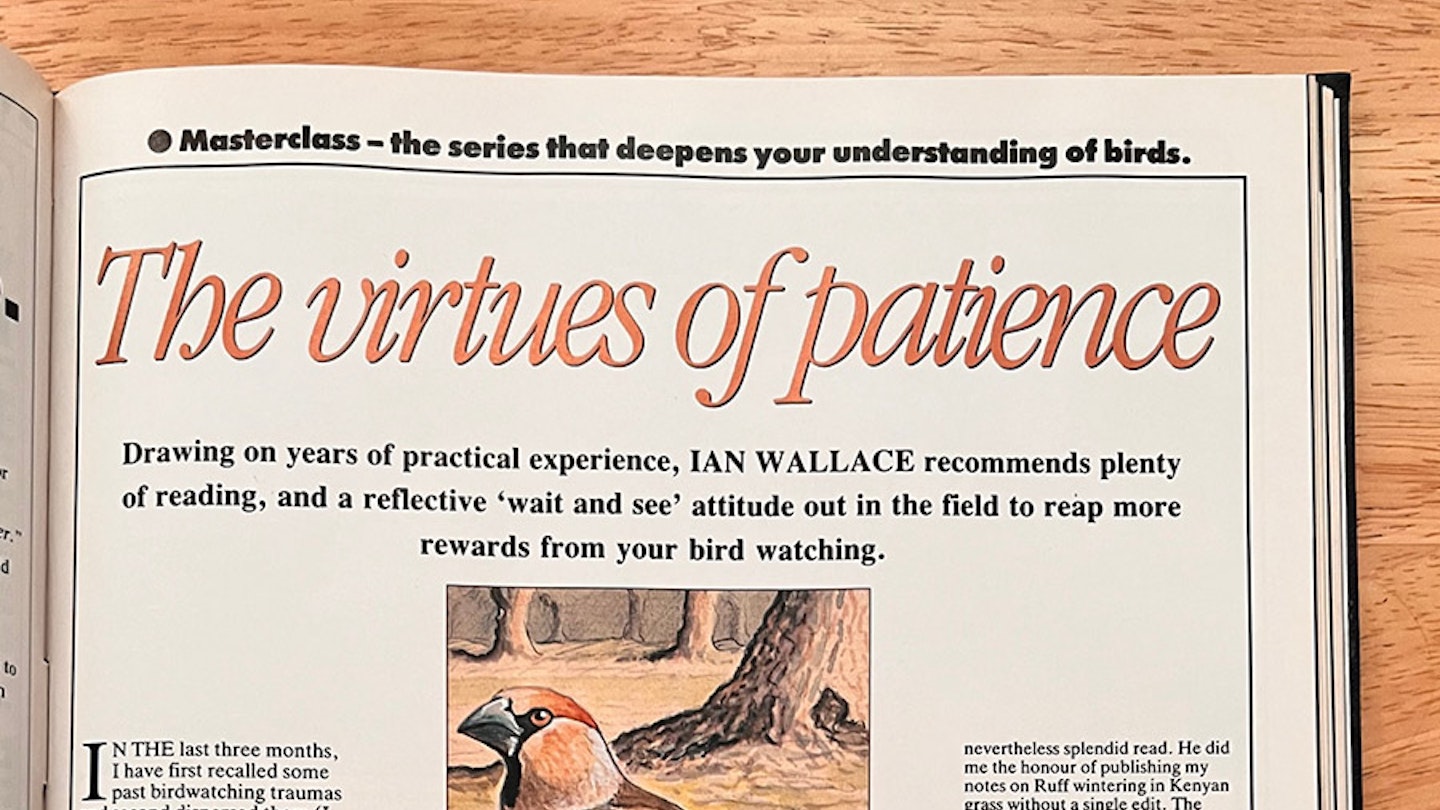

So began a long period of greedy reading, with the early titles of the Collins ‘New Naturalist’ series particularly devoured. The social echoes of Brian Vesey-Fitzgerald’s “British Game”, the panorama of Frank Fraser-Darling’s “The Natural History of the Highlands and Islands”, the relevance of Max Nicholson’s “Birds and Man” and the oceanic scale of Lockley and Fisher’s “Seabirds” stick most in my mind. The monographs on “The Yellow Wagtail” and “The Hawfinch” gave extra flesh to two of my favourite species.

Fraser-Darling’s book has become a true classic and I still pick it up to be reminded of my early enthusiasms and Scottish holidays, full of Dad climbing ahead of me and the occasional new bird.

Later-discovered ‘open sesames’ were Colonel Meinertzhagen’s “The Birds of Arabia” – a good investment for a start – and Vouss’s imaginative “Atlas of European Birds”. The former spawned a desire for a desert experience, glimpsed in Libya and Sudan in 1952, and fulfilled in Jordan and Baluchistan in the next two decades. The latter set seemingly British species in their full Old World ranges and its maps were complemented by a set of really useful black-and-white photographs.

Both encouraged my growing perception of birds as monitors of ecosystems, a strategem fostered particularly in the 1960s by Max Nicholson who was then the brilliant leader of the Nature Conservancy and an inspiring tutor. Its development into an obsession with counting common birds sustains my allegiance to the BTO and NCC initiatives of recent years.

In its perception of 19th Century traditions, Dr Bannerman’s “The Birds of the British Isles” in seven volumes, was a discursive but nevertheless splendid read. He did me the honour of publishing my notes on Ruff wintering in Kenyan grass without a single edit. The ‘good ladies’ – the Scottish Misses Rintoul and Baxter – gave us “The Birds of Scotland’’, a ready solace to too many field days in England.

And to keep alive my early African birdwatching, there was the cherub-like, bespectacled Reg Moreau’s marvellously Olympian treatises, such as “The Bird Faunas of Africa and its Islands” Even ducks got a decent press when the Nature Conservancy’s “Wildfowl in Britain” displayed both the locations and concentration scales of the populations alongside some of Peter Scott’s best paintings.

By the mid-1960s, there was no excuse for ornithological illiteracy. My generation had been well served and by far more than today’s identification monograph after field guide. We were offered, and consumed, a part-traditional and part-rapidly evolving literature. Its value was inestimable.

Among my Scottish mentors, in the 1950s, the favoured fieldguide was as likely to be Wardlaw Ramsay’s “ Guide to the Birds of Europe and North Africa” as the first edition of Peterson.

Wardlaw who? A remarkable Lowland Scot, born a gentleman, educated at Harrow, commissioned to the Hampshires in January 1871, he survived the dangerous Afghan campaign, transferred to the Highland Light Infantry and carried on to become a Territorial Brigadier in the Great War. He performed on the way many other civil and charitable duties in the Lothians, and in the meantime described eight new Oriental species, passing on the famous Tweedle ornithology (skins and books) to the nation and ending up as President of the BOU from 1913 to 1918. Phew!

During his Presidency, Wardlaw Ramsay realised that a concise pocket guide was “a great desideratum” and had, at the time of his death in 1921, all but completed one. Two other 19th Century giants – Eagle Clarke of Fair Isle’s early shotgun days and Surgeon-Rear-Admiral Stanhouse – saw it through to the bookshops.

Wardlaw Ramsay’s 70 years was no mean life. Amazingly, he is all but forgotten in our rushing years, but his book is a systematically accurate set of texts on order, family, genus, species and subspecies. For brief clarity, they have never been surpassed. He even remembered to complement plumages with standard measurements, something which, with few exceptions, modern field guides ignorantly ignore (double stress intended).

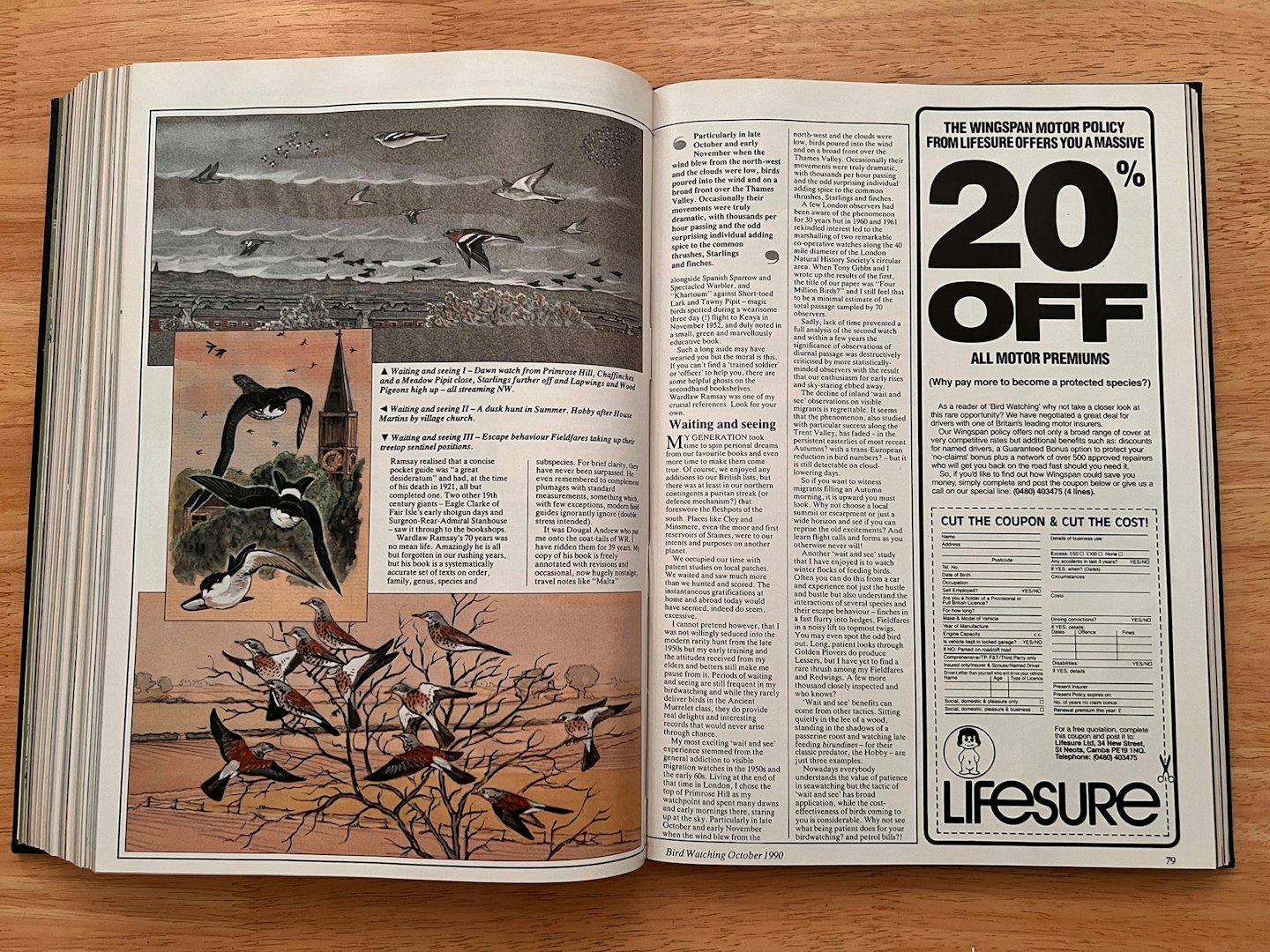

“Particularly in late October and early November, when the wind blew from the north-west and the clouds were low, birds poured into the wind and on a broad front over the Thames Valley. Occasionally their movements were truly dramatic, with thousands per hour passing and the odd surprising individual adding spice to the common thrushes, Starlings and finches.”

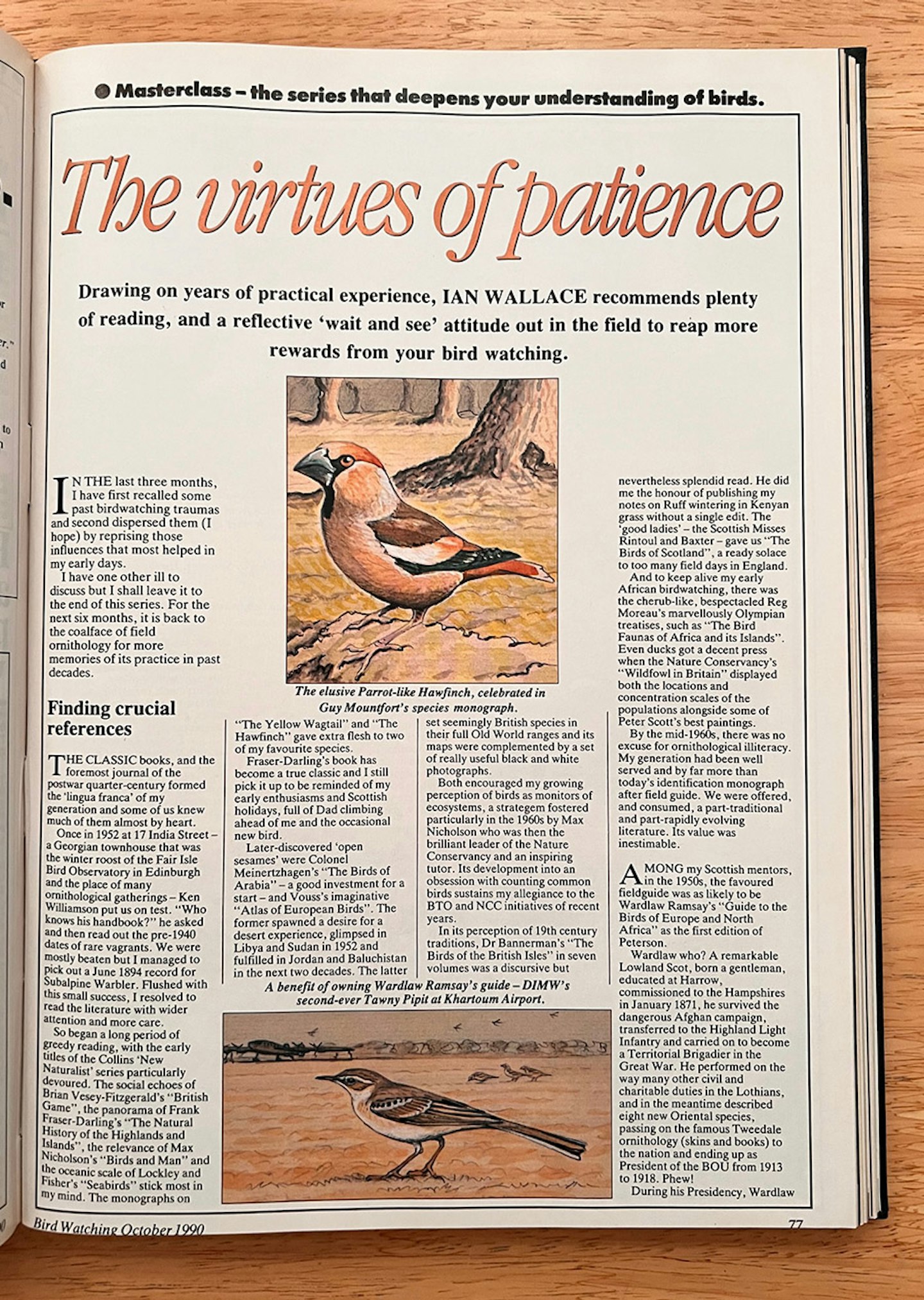

It was Dougal Andrew who put me onto the coat-tails of WR. I have ridden them for 39 years. My copy of his book is freely annotated with revisions and occasional, now hugely nostalgic, travel notes like “Malta” alongside Spanish Sparrow, and Spectacled Warbler, and “Khartoum” against Short-toed Lark and Tawny Pipit – magic birds spotted during a wearisome three day (!) flight to Kenya in November 1952, and duly noted in a small, green and marvellously educative book.

Such a long aside may have wearied you but the moral is this. If you can’t find a ‘trained soldier’ or ‘officer’ to help you, there are some helpful ghosts on the secondhand bookshelves. Wardlaw Ramsay was one of my crucial references. Look for your own.

Waiting and seeing

My generation took time to spin personal dreams from our favourite books and even more time to make them come true. Of course, we enjoyed any additions to our British lists, but there was at least in our northern contingents a puritan streak (or defence mechanism?) that foreswore the fleshpots of the south. Places like Cley and Minsmere, even the moor and first reservoirs of Staines, were to our intents and purposes on another planet.

We occupied our time with patient studies on local patches. We waited and saw much more than we hunted and scored. The instantaneous gratifications at home and abroad today would have seemed, indeed do seem, excessive.

I cannot pretend, however, that I was not willingly seduced into the modern rarity hunt from the late 1950s, but my early training and the attitudes, received from my elders and betters, still make me pause from it. Periods of waiting and seeing are still frequent in my birdwatching, and while they rarely deliver birds in the Ancient Murrelet class, they do provide real delights and interesting records that would never arise through chance.

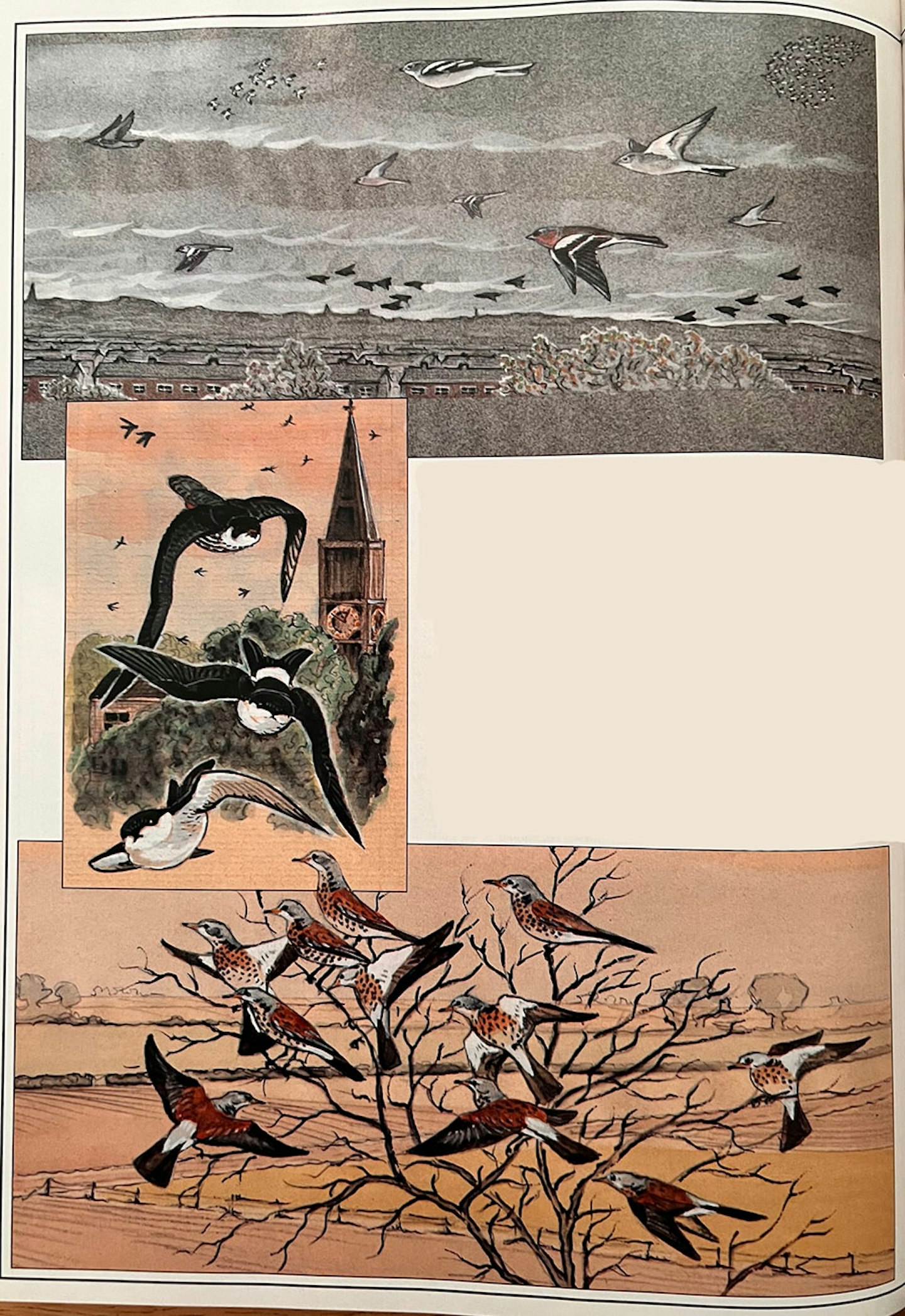

My most exciting ‘wait and see’ experience stemmed from the general addiction to visible migration watches in the 1950s and the early 1960s. Living at the end of that time in London, I chose the top of Primrose Hill as my watchpoint and spent many dawns and early mornings there, staring up at the sky. Particularly in late October and early November, when the wind blew from the north-west and the clouds were low, birds poured into the wind and on a broad front over the Thames Valley. Occasionally, their movements were truly dramatic, with thousands per hour passing and the odd surprising individual adding spice to the common thrushes, Starlings and finches.

A few London observers had been aware of the phenomenon for 30 years, but in 1960 and 1961 rekindled interest led to the marshalling of two remarkable co-operative watches along the 40 mile diameter of the London Natural History Society’s circular area. When Tony Gibbs and I wrote up the results of the first, the title of our paper was “Four Million Birds?” and I still feel that to be a minimal estimate of the total passage sampled by 70 observers.

Sadly, lack of time prevented a full analysis of the second watch, and within a few years the significance of observations of diurnal passage was destructively criticised by more statistically-minded observers, with the result that our enthusiasm for early rises and sky-staring ebbed away.

The decline of inland ‘wait and see’ observations on visible migrants is regrettable. It seems that the phenomenon, also studied with particular success along the Trent Valley, has faded – in the persistent easterlies of most recent autumns? with a trans-European reduction in bird numbers? – but it is still detectable on cloud-lowering days.

So if you want to witness migrants filling an autumn morning, it is upward you must look. Why not choose a local summit or escarpment or just a wide horizon and see if you can reprise the old excitements? And learn flight calls and forms as you otherwise never will!

Another ‘wait and see’ study that I have enjoyed is to watch winter flocks of feeding birds. Often you can do this from a car and experience not just the hustle and bustle but also understand the interactions of several species and their escape behaviour – finches in a fast flurry into hedges, Fieldfares in a noisy lift to topmost twigs.

You may even spot the odd bird out. Long, patient looks through Golden Plovers do produce Lessers [now called Pacific American Golden Plovers), but I have yet to find a rare thrush among my Fieldfares and Redwings. A few more thousand closely inspected and who knows?

‘Wait and see’ benefits can come from other tactics. Sitting quietly in the lee of a wood, standing in the shadows of a passerine roost and watching late feeding hirundines – for their classic predator, the Hobby – are just three examples.

Nowadays everybody understands the value of patience in seawatching but the tactic of

‘wait and see’ has broad application, while the cost-effectiveness of birds coming to you is considerable. Why not see what being patient does for your birdwatching? And petrol bills?!