The appliance of science...

September 1990

Looking back over his early experiences, Ian Wallace highlights the key factors in his birdwatching development, and asks if the current generation will ever be able to recapture the old spirit.

To my mind, the way to expertise does not differ in principle from that in any other pursuit. It is long, and should be full of application, learning, trial and corrected error, more trial, acceptance of constructive criticism, adjustment of approach, more trial and so on, with some fun on occasion to avoid dull Jack.

To learn the ropes fully, you have to stay in the ring and keep your eyes open. Even in my fifth decade, I still puzzle continually about what I see.

As I have already indicated in this series, it was relatively easy for the members of my birdwatching generation to assimilate the basic questions and answers of avian science and so contribute fairly promptly to field ornithology. Our world was much smaller and if you showed promise, the elders of local societies or clubs were wont to pounce upon you and order yet more work.

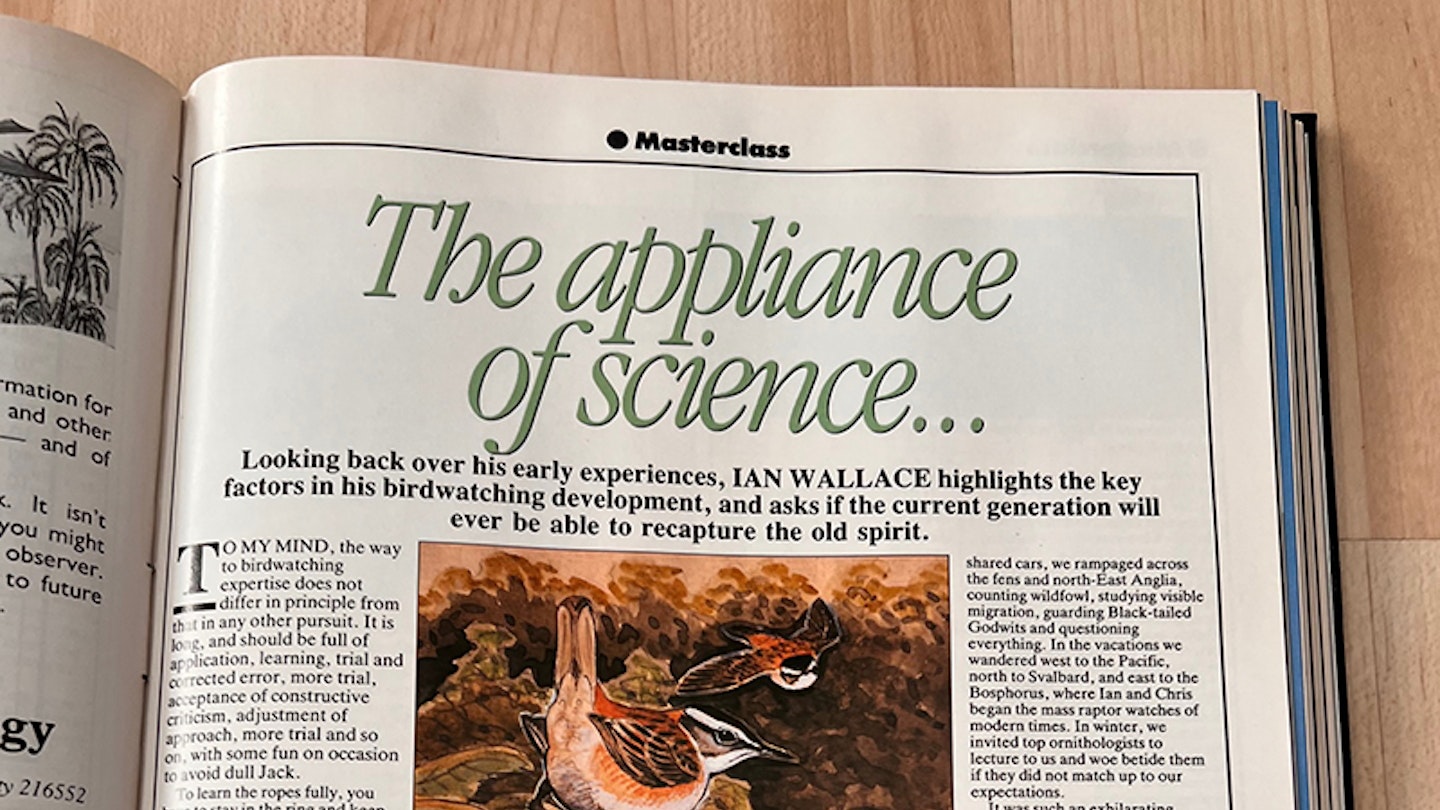

This was never more the case when back from chasing the Mau Mau in Kenya, I duly reported to Cambridge and bent somewhat reluctantly to the task of degree-getting. Before I had found the time even to bike out to the then famous Cambridge Sewage Farm – breeding ‘Moustached Warblers’ and the like? – I was visited in my rooms by the scholarly Chris Smout, then second only to the brilliant Ian Nisbet in the University’s birdwatching circles.

Although friendly, Chris’ attitude left me in little doubt that his visit was actually a vetting, inquisitorial almost to the point of Jesuit zeal. Clearly I was not going to be allowed just to enjoy birds. I was expected fully to join in the enquiries of the Cambridge Bird Club which extended then to four counties!

So, the years of 1954-5, 1955-6 and 1956-7 saw me serve before and behind the mast of the most adventurous ship in post-war British birdwatching. The crew’s other members included Clive Minton (wader trapper extraordinary, still active in Australia), Tony Vine (Fen expert and first speaker in the Marsh Hawk [aka Northern Harrier]/unstreaked juvenile Hen Harrier debate), Bill Bourne (terrifying if you upset him, but an ornithological tour de force), Graham Easy (no mean artist and still loyal to the county) and a small host of others who went home to make their marks in their native counties in due course.

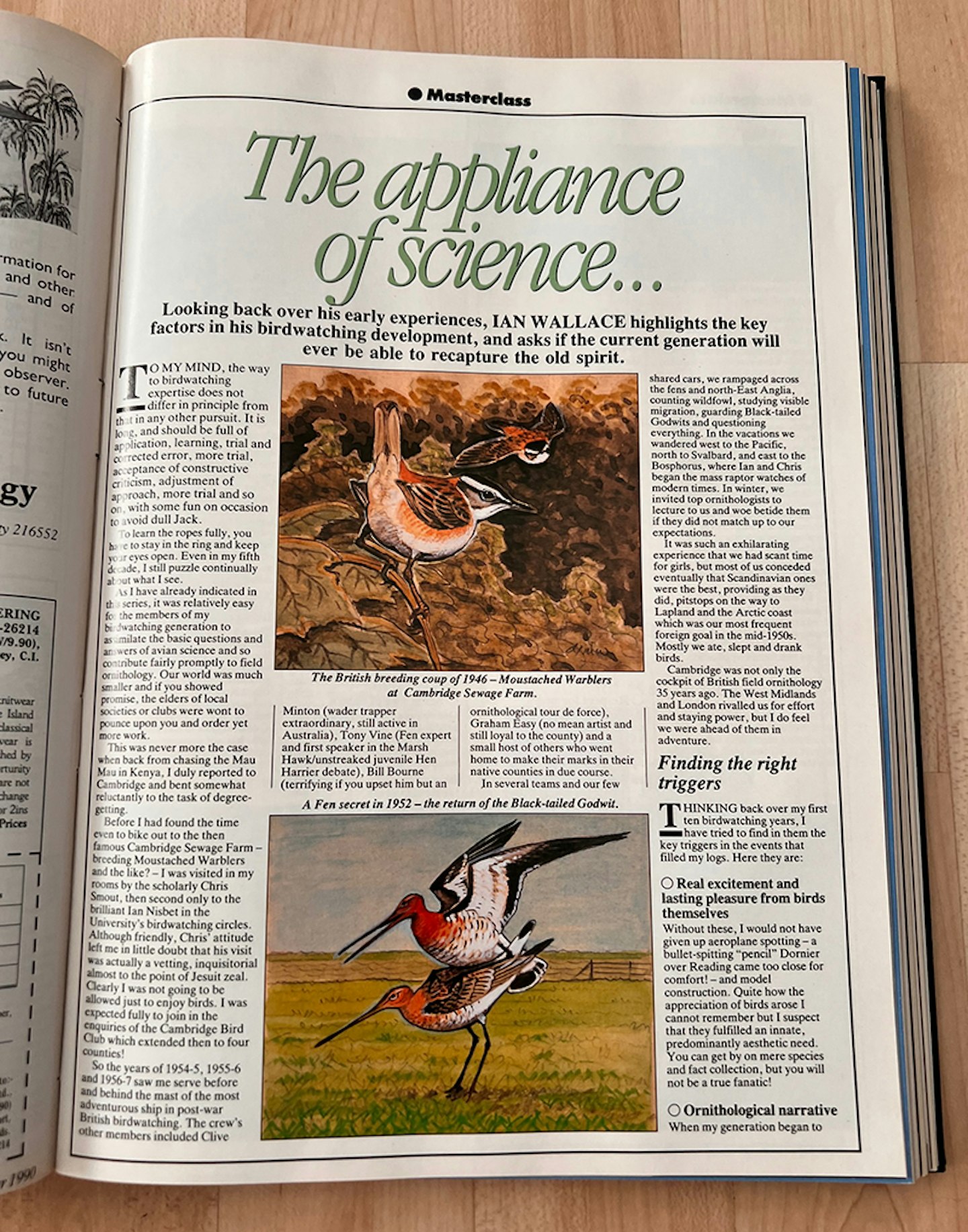

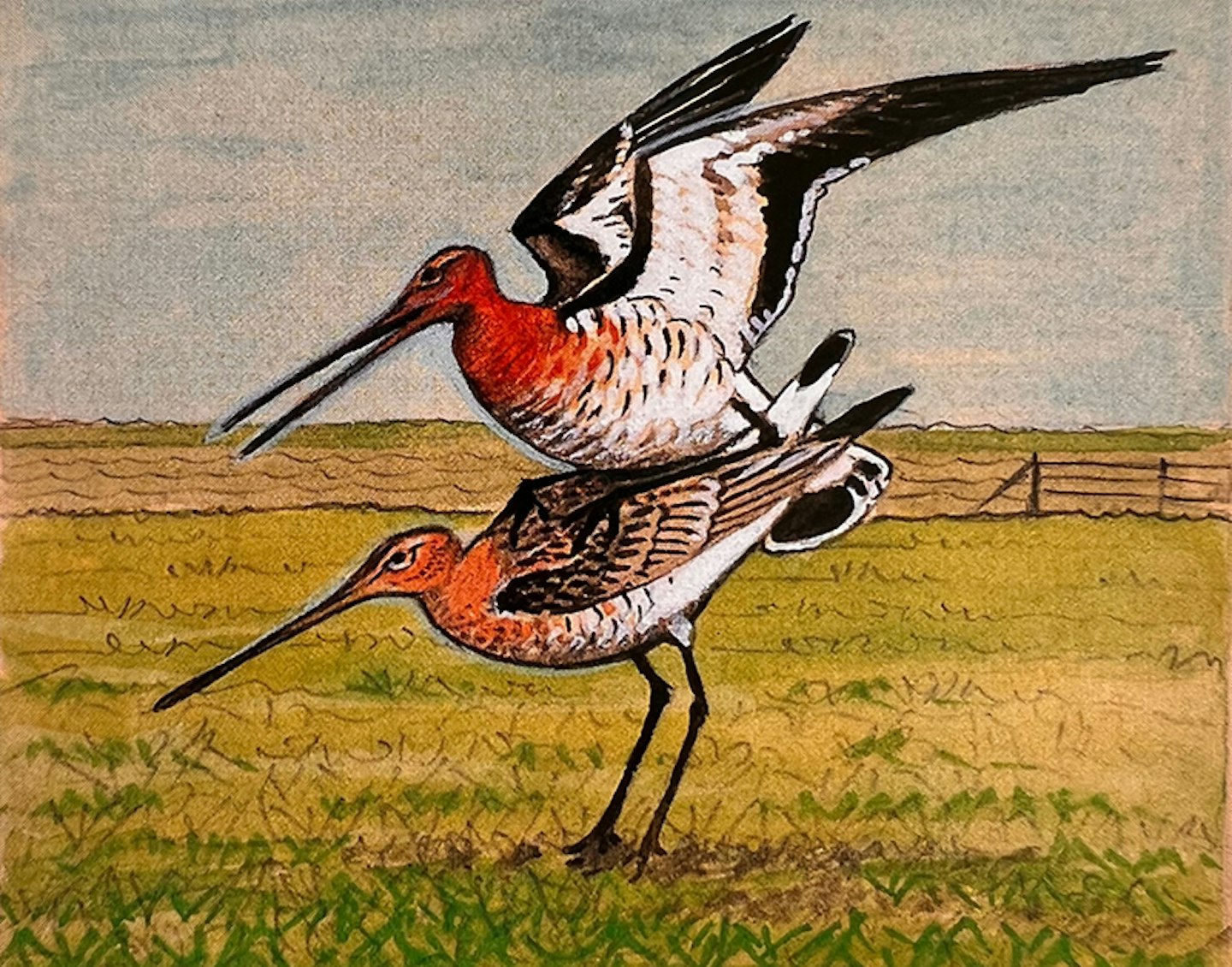

In several teams and our few shared cars, we rampaged across the fens and north East Anglia, counting wildfowl, studying visible migration, guarding Black-tailed Godwits and questioning everything. In the vacations, we wandered west to the Pacific, north to Svalbard, and east to the Bosphorus, where Ian and Chris began the mass raptor watches of modern times. In winter, we invited top ornithologists to lecture to us and woe betide them if they did not match up to our expectations.

It was such an exhilarating experience that we had scant time for girls, but most of us conceded eventually that Scandinavian ones were the best, providing as they did, pitstops on the way to Lapland and the Arctic coast which was our most frequent foreign goal in the mid-1950s.

Mostly, we ate, slept and drank birds. Cambridge was not only the cockpit of British field ornithology 35 years ago [ie the mid 1950s]. The West Midlands and London rivalled us for effort and staying power, but I do feel we were ahead of them in adventure.

Finding the right triggers

Thinking back over my first 10 birdwatching years, I have tried to find in them the key triggers in the events that filled my logs. Here they are:

1 Real excitement and lasting pleasure from birds themselves

Without these, I would not have given up aeroplane spotting – a bullet-spitting “pencil” Dornier over Reading came too close for comfort! – and model construction. Quite how the appreciation of birds arose I cannot remember but I suspect that they fulfilled an innate, predominantly aesthetic need. You can get by on mere species and fact collection, but you will not be a true fanatic!

2 Ornithological narrative

When my generation began to watch birds, our libraries were full of liberal, well-written prose rather than spartan, even colourless notes. Accordingly, our dreams were immediately fostered by other mature human appreciations of birds and our studies were impeded neither by more disciplines than the necessary few hence, ever-present enthusiasm), nor by more car miles driven than birds inspected (ie. twitching had not been invented). Books like Abel Chapman’s The Borders and Beyond, Peter Scott’s Dawn Flight and Morning Chorus and the tales of the postwar photographers both taught and entertained us. Somehow, in spite of all our recent explorations of furthest wildernesses, the inspiration afforded by the early adventurers has lasted longer than any tour report.

3 Friendly science

For solitary youths, trustworthy books on bird identification and biology were hard to find, but there were usually three stepping stones to scientific application. The first varied between three titles; mine was Edmund Sandars’ Bird Book for the Pocket. The second was T. A. Coward’s The Birds of the British Isles, resplendent with Archibald Thorburn’s marvellous paintings of truly glamorous birds. The third was the old and still evocative “Handbook”.

I well remember begging Dad for the Coward and promising that it would be the end of his investment in my hobby, on top of my ex-German Navy 6×30s. How I grovelled when I discovered that the five volumes of the Handbook were the then ultimate bird books.

What characterised all the old books was their warmth and evident humanity, with observers’ names sprinkled everywhere in a signal to us that our contributions would be welcome, too. True, they had frustrating gaps in them but those were precisely our study opportunities.

4 Regular stimulus

Two publications gave us this. In a local context, it was the county report – already by the 1950s well developed in most areas with fact-contributing observers – and for the national scene, there was British Birds, approaching its half-century and the central voice of active birdwatchers. Later Bird Study and briefly Bird Migration took us into purposeful science but for the aesthete, BB was magical in its spur to effort.

5 Respect for peers

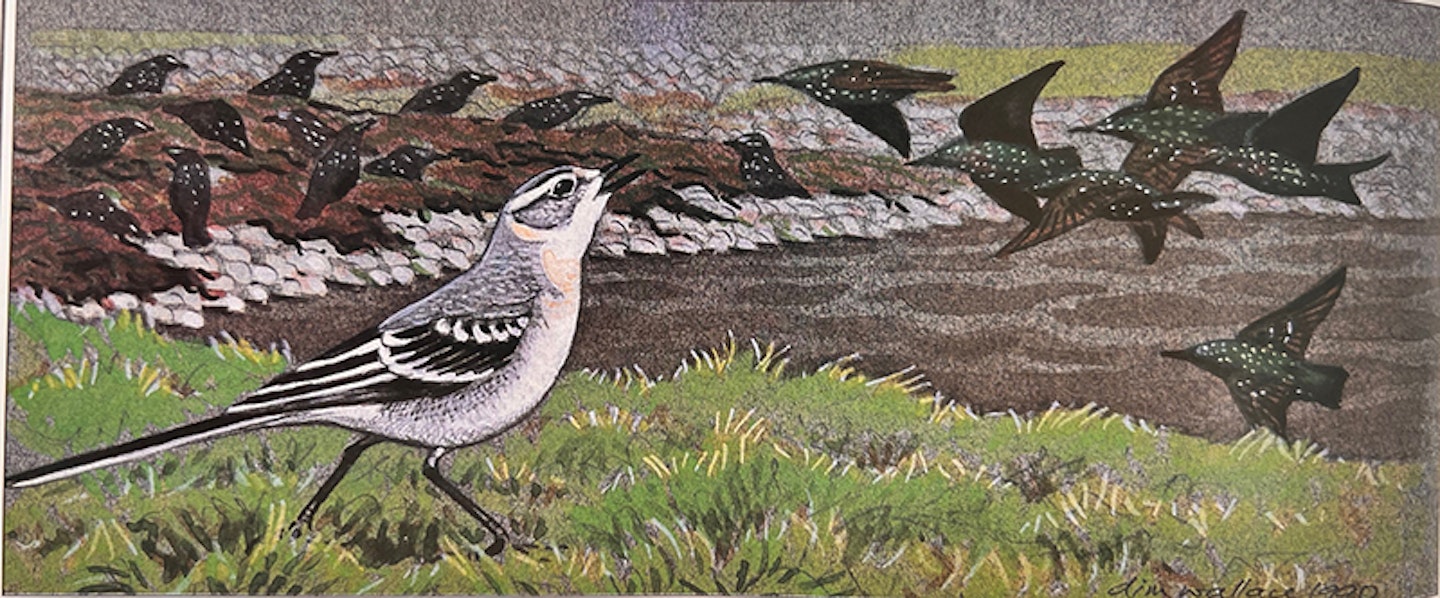

Because so many of us had developed our hobby individually and spontaneously, we treated each other on first meetings as equals, experiencing little but mild envy at the news of others’ discoveries. This shared attitude built confidence and fostered painless error correction. It also made task-sharing automatic. By the time that I got to the fenland washes, too many stares at London’s reservoirs had put me right off ducks. But if I was to have my amazing variant Yellow Wagtails supported, some reciprocal wildfowl counts just had to be done. Again, if it was the dawn shift at Hunstanton and an attempt on the world record Sky Lark passage, we did just that – rarities elsewhere not withstanding. Ye Gods, I once did such chores for three weekends and so missed a “sitting duck” White-tailed Eagle.

6 Some awe of elders

Our attitude to the ornithological establishment was mixed. As you will have gathered, we were inspired by the adventurers (even when they got things wrong) but we were not all that happy with the early media personalities, particularly the list-greedy James Fisher who could over-bear with walrus weight. Sadly, in retrospect, we virtually ignored the true scientists, like our own Dr Thorpe of Madingly and bird song learning fame. This was our main fault; as ornithological hunter-gatherers, we scored mainly in the first half of that term.

7 Desire to contribute to field ornithology

This was expressed in two ways, firstly in our contributions to the literature of the times and secondly in our enthusiasm for spreading the word and leading other observers.

I can think of no front-and-middle rank amateur at Cambridge or London in the 1950s who has not written about birds and/or served in some group role in birdwatching. Today, some of their names ring only faintly, but did you know that one of the late Peter Grant’s first studies was of the birds of Greenwich Park, a far cry from Eilat and the inner greater coverts of stints? He took his cue from Inner London studies of inevitably common birds. I still remember his pride in his first Thames-crossing migrant Siskins!

8 Reluctant obsession

Perhaps unwittingly, we suffered little from obsessions or the single drive for compulsive list-building now so evident in twitching. Many of us regularly lost count of our life lists in a time when debates and work on “drift migration”, “ectoparasites”, “wildfowl counts” (again), “visible passage”, “moult**,** “bird weight”, “racial taxonomy”, and a long list of other subjects compressed rarities into the odd jolly in May and a bit more regular bush-bashing in September. October had not been invented!

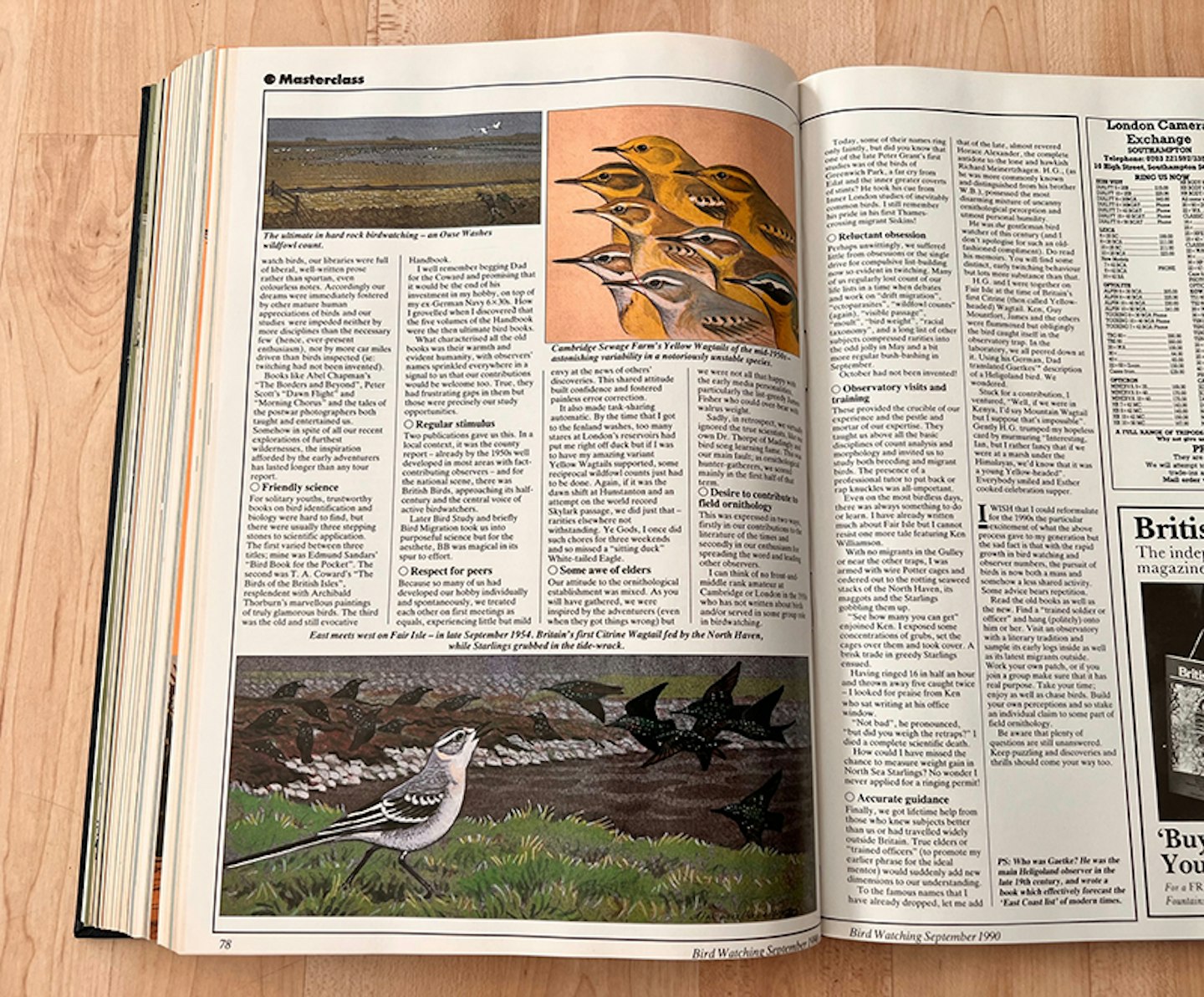

9 Observatory visits and trainingThese provided the crucible of our experience and the pestle and mortar of our expertise. They taught us above all the basic disciplines of count analysis and morphology and invited us to study both breeding and migrant birds. The presence of a professional tutor to pat back or rap knuckles was all-important. Even on the most birdless days, there was always something to do or learn. I have already written much about Fair Isle but I cannot resist one more tale featuring Ken Williamson. With no migrants in the Gulley or near the other traps, I was armed with wire Potter cages and ordered out to the rotting seaweed stacks of the North Haven, its maggots and the Starlings gobbling them up. “See how many you can get” enjoined Ken. I exposed some concentrations of grubs, set the cages over them and took cover. A brisk trade in greedy Starlings ensued. Having ringed 16 in half an hour and thrown away five caught twice – looked for praise from Ken who sat writing at his office window “Not bad”, he pronounced, “but did you weigh the retraps?” I died a complete scientific death. How could I have missed the chance to measure weight gain in North Sea Starlings? No wonder I never applied for a ringing permit!

10 Accurate guidance

Finally, we got lifetime help from those who knew subjects better than us or had travelled widely Outside Britain. True elders or “trained officers” (to promote my earlier phrase for the ideal mentor) would suddenly add new dimensions to our understanding. To the famous names that have already dropped, let me add that of the late, almost revered Horace Alexander, the complete antidote to the lone and hawkish Richard Meinertzhagen. H.G., (as he was more commonly known and distinguished from his brother W.B.), possessed the most disarming mixture of uncanny ornithological perception and utmost personal humility. He was the gentleman birdwatcher of this century (and I don’t apologise for such an old-fashioned compliment). Do read his memoirs. You will find some distinct, early twitching behaviour but lots more substance than that.

H.G. and I were together on Fair Isle at the time of Britain’s first Citrine (then called Yellow-headed) Wagtail. Ken, Guy Mountfort, James and the others were flummoxed but, obligingly, the bird caught itself in the observatory trap. In the laboratory, we all peered down at it. Using his German, Dad translated Gaetkes’ description of a Heligoland bird. We wondered.

Stuck for a contribution, I ventured, “Well, if we were in Kenya, I’d say Mountain Wagtail but I suppose that’s impossible”. Gently, H.G. trumped my hopeless card by murmuring “Interesting, Ian, but I rather fancy that if we were at a marsh under the Himalayas, we’d know that it was a young Yellow-headed” Everybody smiled and Esther cooked a celebration supper.

I wish that I could reformulate for the 1990s the particular excitement of what the above process gave to my generation but the sad fact is that with the rapid growth in birdwatching and observer numbers, the pursuit of birds is now both a mass and somehow a less shared activity. Some advice bears repetition. Read the old books as well as the new. Find a “trained soldier or officer” and hang (politely) onto him or her. Visit an observatory with a literary tradition and sample its early logs inside as well as its latest migrants outside. Work your own patch, or if you join a group make sure that it has real purpose. Take your time; enjoy as well as chase birds. Build your own perceptions and so stake an individual claim to some part of field ornithology. Be aware that plenty of questions are still unanswered. Keep puzzling and discoveries and thrills should come your way too.

PS: Who was Gaetke? He was the main Heligoland observer in the late 19th Century, and wrote a book which effectively forecast the East Coast list’ of modern times.