August 1990

The fallibility factor

How many birdwatchers are brave enough to own up when they misidentify a bird? How many can keep cool when their judgment is challenged? Ian Wallace discusses these two emotive topics.

Errors in ornithology come in two main guises: simple confusions of identity and more complex misjudgments of status. Behavioural misconceptions can be similarly widespread but seem these days to be committed less often than in the 1950s and 1960s, due perhaps to the narrowing interests of the amateur ornithologist. So, it makes sense to discuss his or her fallibility in its most overt context: the British list of birds and their identifications.

Thirty-five years ago [i.e. in the mid 1950s] the compulsive, competitive amassing of 400-plus species in Britain was a non-pursuit. I remember Dougal Andrew seriously proposing a special club and tie for those observers who had reached 250. We presumed that this total would most likely coincide with retirement from the field and a deck chair. How wrong we were!

The arrival in 1959 of the British Birds Rarities Report placed new national values on some uncommon and all rare birds, and unwittingly these proved to be an irresistible score sheet. Inexorably, from listing or ticking came twitching, now the dominant goal of many young birders. Recently, I spent a few hours with a 25-year-old who had already 401 species to his British credit! Incredible, but true!

A direct product of avid species collection (and the disciplines applied to it) has been an increase in the human pressures felt by observers. Dangers threaten in debates on tricky identifications or strange occurrences, and are at their extreme in controversies. The avian desires are understandable; the human foibles likewise, but occasionally their presentation has been manic and unacceptable. So I ask who today owns up? And how do you keep your cool?

Owning up

One day, in August 1946, I saw a chat flit along the parapet of the Kinloch Rannoch bridge and then dive into a bank of whins (broom in England). It looked blue somewhere and red on its tail. I knew that it was a new bird for me; I wanted it to be rare. At 13 tender years, I knew Robin, Wheatear and Whinchat and it was none of them.

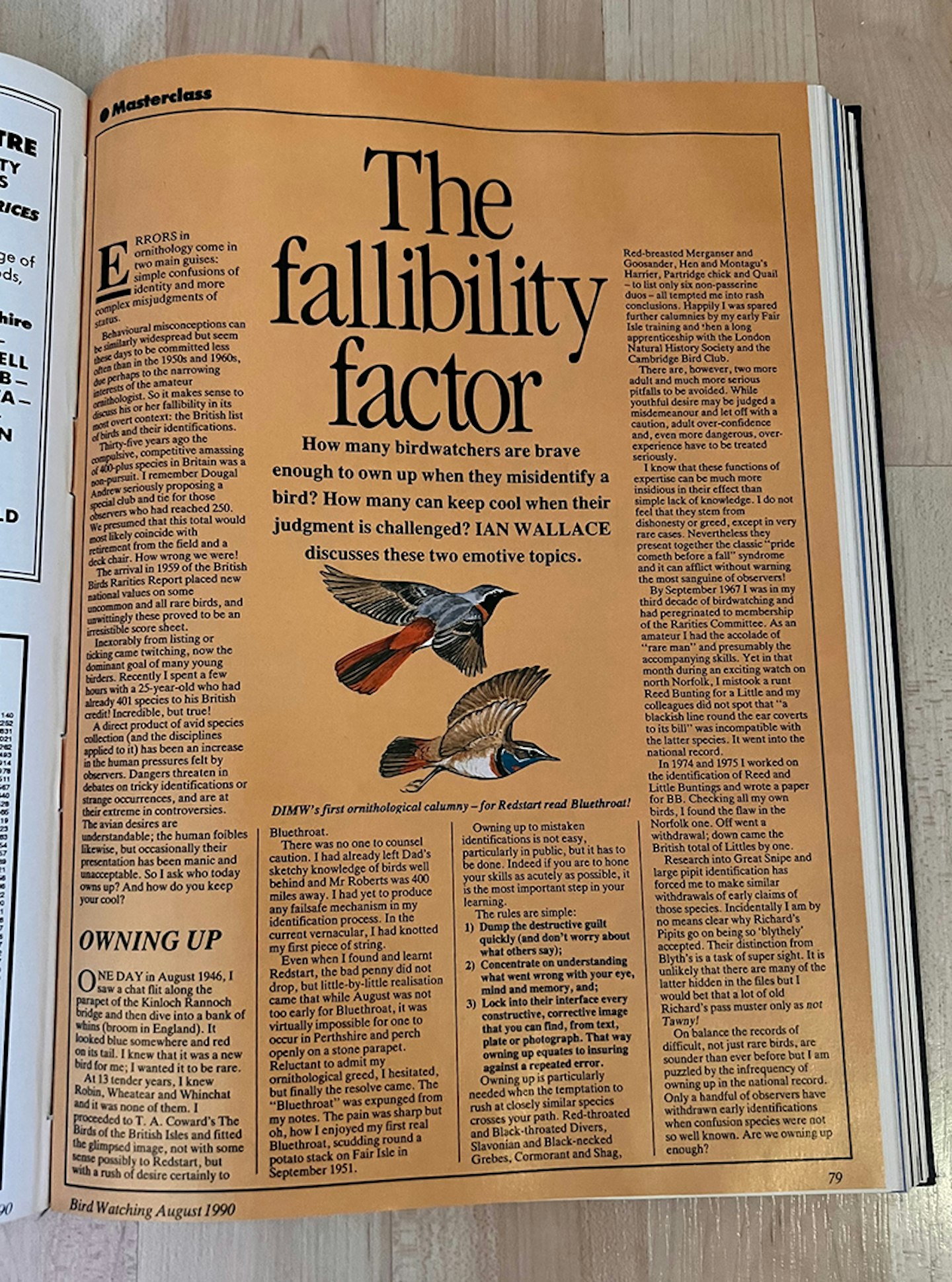

I proceeded to T. A. Coward’s The Birds of the British Isles and fitted the glimpsed image, not with some sense possibly to Redstart, but with a rush of desire certainly to Bluethroat. There was no one to counsel caution. I had already left Dad’s sketchy knowledge of birds well behind and Mr Roberts was 400 miles away. I had yet to produce any failsafe mechanism in my identification process.

In the current vernacular, I had knotted my first piece of string. Even when I found and learnt Redstart, the bad penny did not drop, but little-by-little realisation came that while August was not too early for Bluethroat, it was virtually impossible for one to occur in Perthshire and perch openly on a stone parapet. Reluctant to admit my ornithological greed, I hesitated, but finally the resolve came. The “Bluethroat” was expunged from my notes.

The pain was sharp but oh, how I enjoyed my first real Bluethroat, scudding round a potato stack on Fair Isle in September 1951. Owning up to mistaken identifications is not easy, particularly in public, but it has to be done. Indeed, if you are to hone your skills as acutely as possible, it is the most important step in your learning.

The rules are simple:

-

Dump the destructive guilt quickly (and don’t worry about what others say);

-

Concentrate on understanding what went wrong with your eye, mind and memory, and;

-

Lock into their interface every constructive, corrective image that you can find, from text, plate or photograph. That way, owning up equates to insuring against a repeated error.

Owning up is particularly needed when the temptation to rush at closely similar species crosses your path. Red-throated and Black-throated Divers; Slavonian and Black-necked Grebes; Cormorant and Shag; Red-breasted Merganser and Goosander; Hen and Montagu’s Harrier; Partridge chick and Quail – to list only six non-passerine duos – all tempted me into rash conclusions. Happily I was spared further calumnies by my early Fair Isle training and then a long apprenticeship with the London Natural History Society and the Cambridge Bird Club.

There are, however, two more adult and much more serious pitfalls to be avoided. While youthful desire may be judged a misdemeanour and let off with a caution, adult over-confidence and, even more dangerous, over-experience have to be treated seriously.

I know that these functions of expertise can be much more insidious in their effect than simple lack of knowledge. I do not feel that they stem from dishonesty or greed, except in very rare cases. Nevertheless they present together the classic “pride cometh before a fall” syndrome and it can afflict without warning the most sanguine of observers!

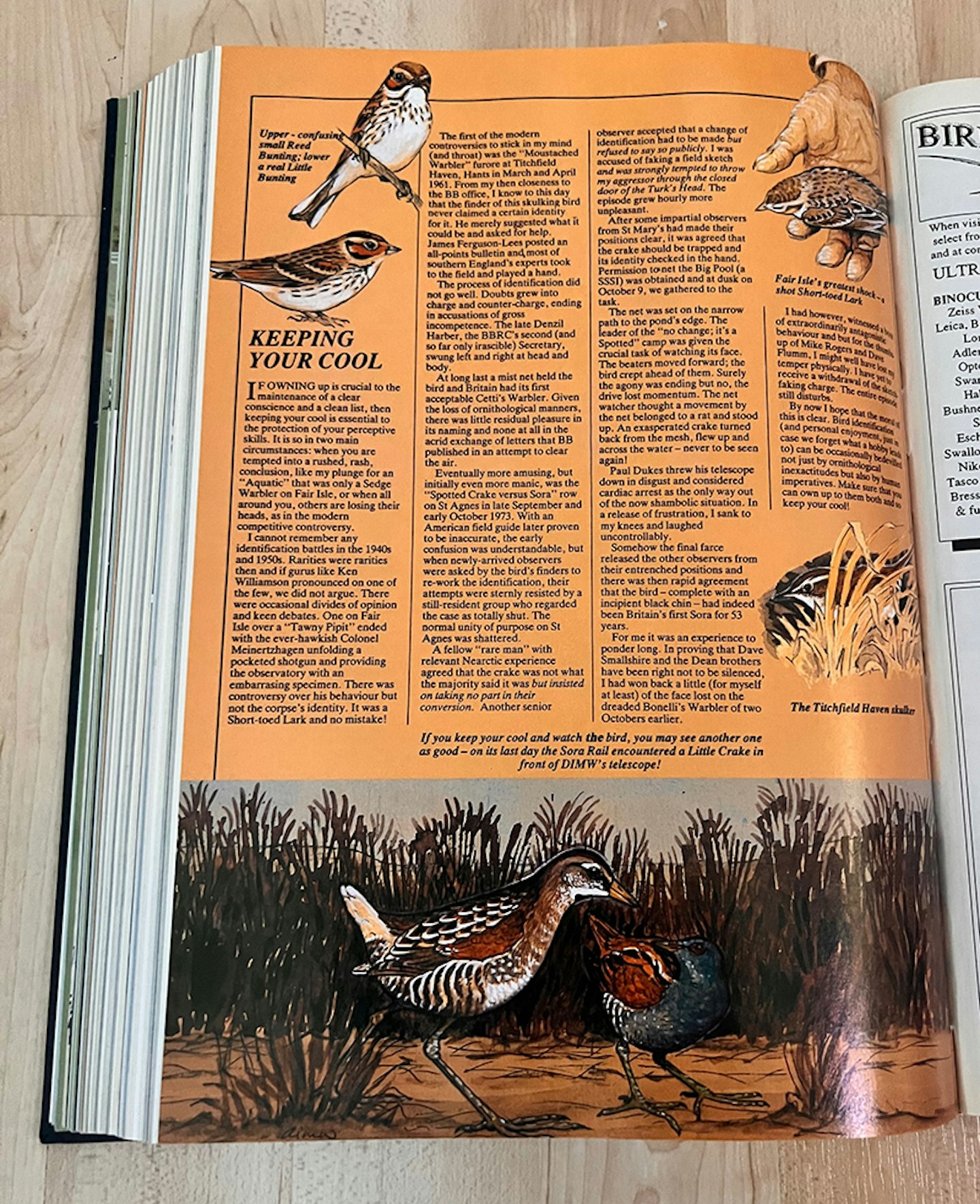

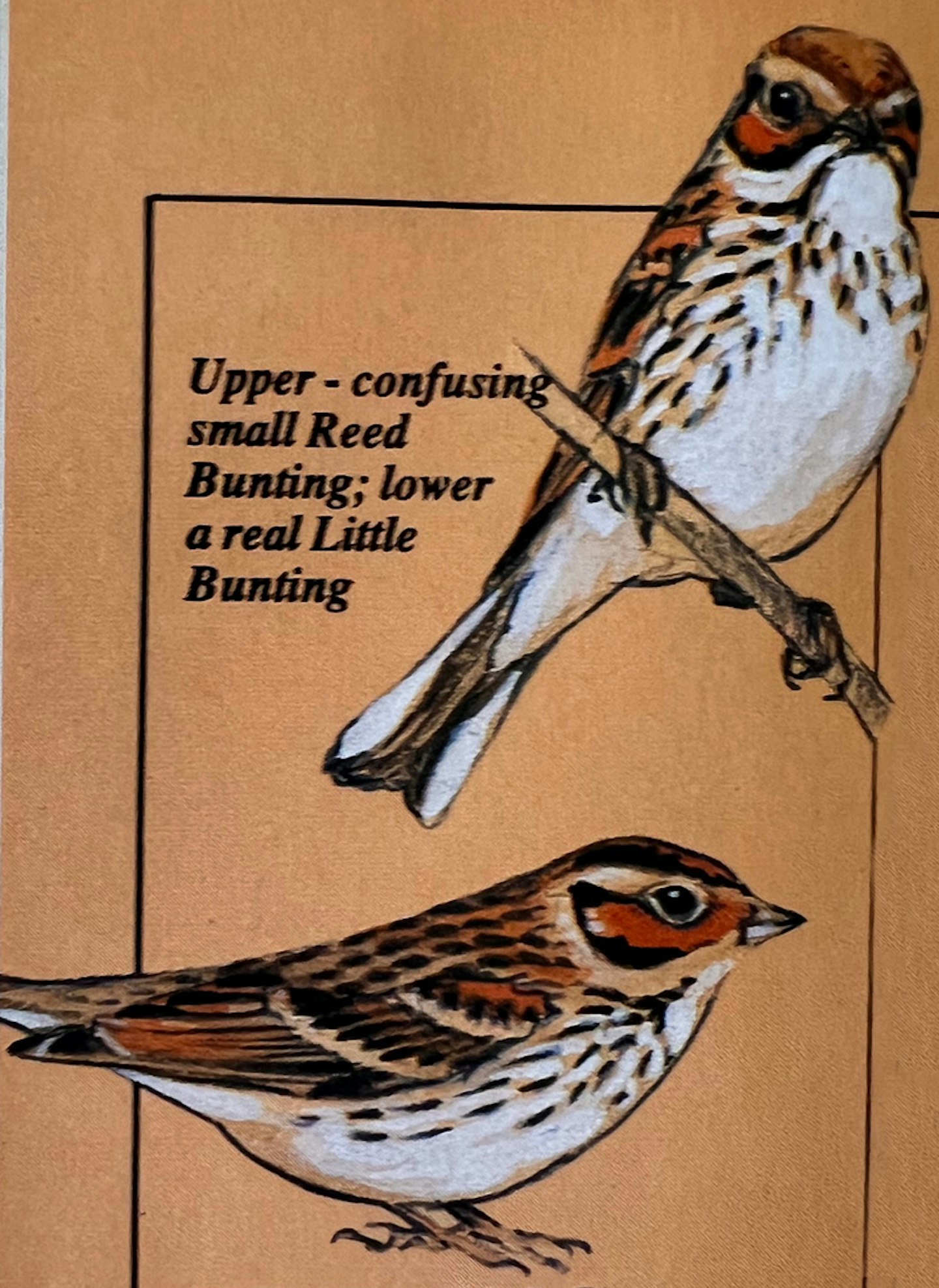

By September 1967, I was in my third decade of birdwatching and had peregrinated to membership of the Rarities Committee. As an amateur I had the accolade of “rare man” and presumably the accompanying skills. Yet, in that month, during an exciting watch on north Norfolk, I mistook a runt Reed Bunting for a Little Bunting and my colleagues did not spot that “a blackish line round the ear coverts to its bill” was incompatible with the latter species. It went into the national record.

In 1974 and 1975, I worked on the identification of Reed and Little Buntings and wrote a paper for BB. Checking all my own birds, I found the flaw in the Norfolk one. Off went a withdrawal; down came the British total of Littles by one.

Research into Great Snipe and large pipit identification has forced me to make similar withdrawals of early claims of those species. Incidentally I am by no means clear why Richard’s Pipits go on being so ‘blythely’ accepted. Their distinction from Blyth’s is a task of super sight. It is unlikely that there are many of the latter hidden in the files, but I would bet that a lot of old Richard’s pass muster only as not Tawny!

On balance, the records of difficult, not just rare birds, are sounder than ever before but I am puzzled by the infrequency of owning up in the national record. Only a handful of observers have withdrawn early identifications when confusion species were not so well known. Are we owning up enough?

Keeping your cool

If owning up is crucial to the maintenance of a clear conscience and a clean list, then keeping your cool is essential to the protection of your perceptive skills. It is so in two main circumstances: when you are tempted into a rushed, rash, conclusion, like my plunge for an “Aquatic” that was only a Sedge Warbler on Fair Isle, or when all around you, others are losing their heads, as in the modern competitive controversy.

I cannot remember any identification battles in the 1940s and 1950s. Rarities were rarities then and if gurus like Ken Williamson pronounced on one of the few, we did not argue. There were occasional divides of opinion and keen debates. One on Fair Isle over a “Tawny Pipit” ended with the ever-hawkish Colonel Meinertzhagen unfolding a pocketed shotgun and providing the observatory with an embarrassing specimen. There was controversy over his behaviour but not the corpse’s identity. It was a Short-toed Lark and no mistake!

The first of the modern controversies to stick in my mind (and throat) was the “Moustached Warbler” furore at Titchfield Haven, Hants, in March and April 1961. From my then closeness to the BB office, I know to this day that the finder of this skulking bird never claimed a certain identity for it. He merely suggested what it could be and asked for help.

James Ferguson-Lees posted an all-points bulletin and most of southern England’s experts took to the field and played a hand. The process of identification did not go well. Doubts grew into charge and counter-charge, ending in accusations of gross incompetence. The late Denzil Harber, the BBRC’s second (and so far only irascible) Secretary, swung left and right at head and body. At long last, a mist net held the bird and Britain had its first acceptable Cetti’s Warbler.

Given the loss of ornithological manners, there was little residual pleasure in its naming and none at all in the acrid exchange of letters that BB published in an attempt to clear the air.

Eventually more amusing, but initially even more manic, was the “Spotted Crake versus Sora” row on St Agnes in late September and early October 1973. With an American field guide later proven to be inaccurate, the early confusion was understandable, but when newly-arrived observers were asked by the bird’s finders to re-work the identification, their attempts were sternly resisted by a still-resident group who regarded the case as totally shut.

The normal unity of purpose on St Agnes was shattered. A fellow “rare man” with relevant Nearctic experience agreed that the crake was not what the majority said it was, but insisted on taking no part in their conversion. Another senior observer accepted that a change of identification had to be made, but I refused to say so, publicly. I was accused of faking a field sketch and was strongly tempted to throw my aggressor through the closed door of the Turk’s Head. The episode grew hourly more unpleasant.

After some impartial observers from St Mary’s had made their positions clear, it was agreed that the crake should be trapped and its identity checked in the hand. Permission to net the Big Pool (a SSSI) was obtained and at dusk on 9 October, we gathered to the task. The net was set on the narrow path to the pond’s edge. The leader of the “no change; it’s a Spotted” camp was given the crucial task of watching its face.

The beaters moved forward; the bird crept ahead of them. Surely, the agony was ending but no, the drive lost momentum. The net watcher thought a movement by the net belonged to a rat and stood up. An exasperated crake turned back from the mesh, flew up and across the water – never to be seen again! Paul Dukes threw his telescope down in disgust and considered cardiac arrest as the only way out of the now shambolic situation.

In a release of frustration, I sank to my knees and laughed uncontrollably. Somehow, the final farce released the other observers from their entrenched positions and there was then rapid agreement that the bird – complete with an incipient black chin – had indeed been Britain’s first Sora for 53 years.

For me, it was an experience to ponder long. In proving that Dave Smallshire and the Dean brothers had been right not to be silenced, I had won back a little (for myself at least) of the face lost on the dreaded Bonelli’s Warbler of two Octobers earlier. I had, however, witnessed a bout of extraordinarily antagonistic behaviour; and but for the thumbs-up of Mike Rogers and Dave Flumm, I might well have lost my temper, physically.

I have yet to receive a withdrawal of the sketch-faking charge! The entire episode still disturbs. By now I hope that the moral of this is clear. Bird identification (and personal enjoyment, just in case we forget what a hobby leads to) can be occasionally bedevilled not just by ornithological inexactitudes but also by human imperatives. Make sure that you can own up to them both and so keep your cool!