Turning sight into perception

July 1990

After issuing some rather hard rock instructions on ornithological writing last month, Ian Wallace returns to the more intriguing parts of birdwatching and tries to show how his generation tempered identification skills in times of both joy and sadness.

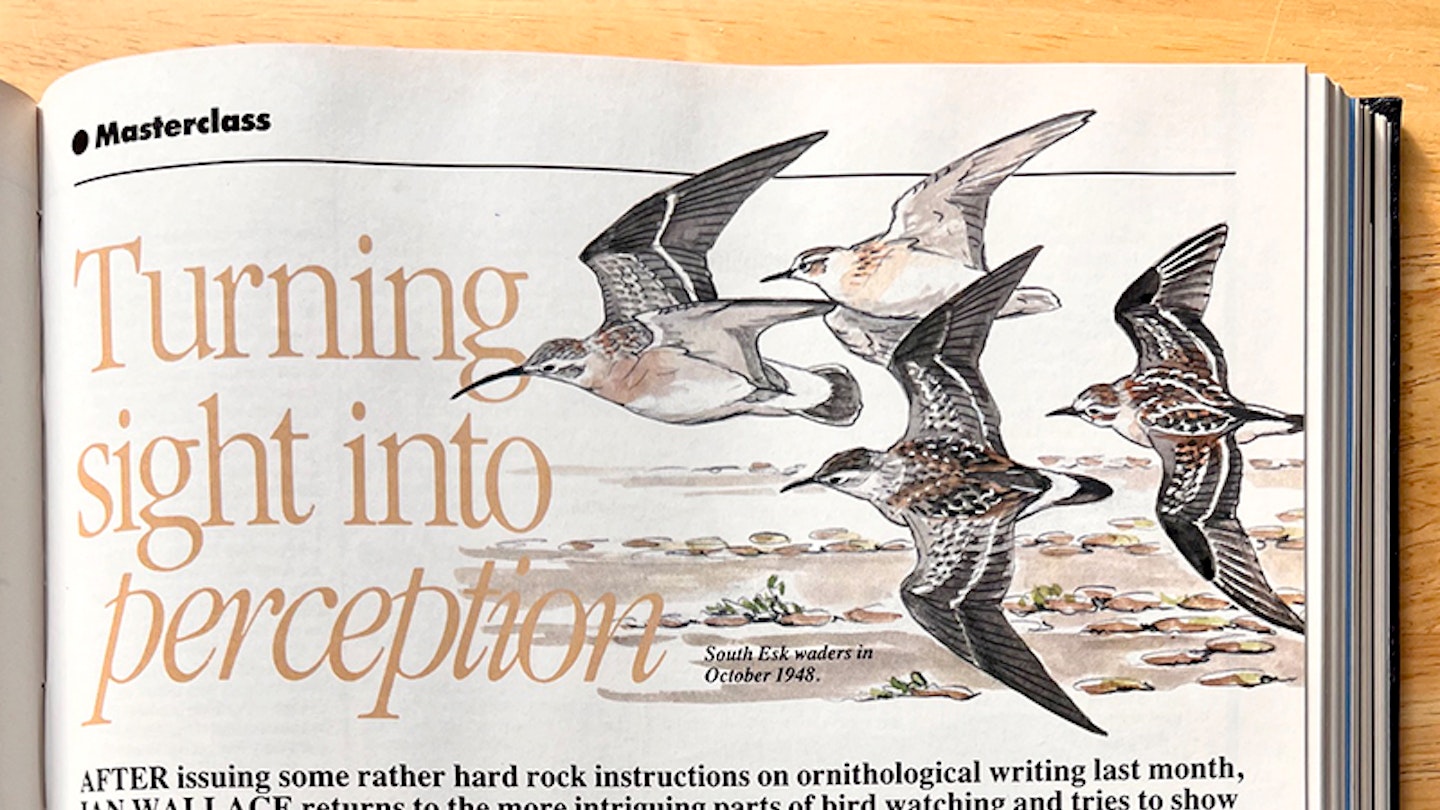

On 9 October, 1948, I found a stint-like wader at the mouth of the South Esk at Musselburgh, Lothian. It struck me as distinctly odd and accordingly I made a coloured sketch of it with its most striking character – an obvious, apparently V-shaped white mark above a dark tail clearly shown. I took it to my schoolmaster, Eek Turner, and trusted the final identification to him.

My first ornithological disaster ensued. Not perceiving relatively minute details as different from bold marks, Eek somehow fitted my sketch to the Handbook’s description of a juvenile Little Stint, wittering on about how sharp-eyed I had been to see the white V over its back and congratulating me in front of the school society on my identification. I sat dumbfounded, knowing for the umpteenth time that the bird had not been a Little Stint, but lacking the courage to correct his interpretation.

Seven years later, Dougal Andrew had a White-rumped Sandpiper at Gladhouse reservoir and his description of it triggered belatedly, but totally, my perception of the Musselburgh bird as that species, incidentally, then called Bonaparte’s Sandpiper. BB was kind enough to give it a footnote mention but, given the loss of the original sketch, there was no chance of beating Dougal to the punch of a Scottish first.

Long irritated by an unclosed Chapter, I finally realised that my fundamental mistake had been to delegate a task that was mine. Above all, I learned not to confuse mere visual acuity with the full perception of a species.

Proving your own identifications

Forty-five years ago, the ink on the Handbook’s pages was barely dry; ornithological groups were mostly small and tender in years; one man – the Editor of BB – frequently combined the roles of local, county and national judges on bird records; the Fitter field guide had not been written; and Peterson was still nine years off.

Young observers, eager to raise their skills, had largely to fend for themselves in usually narrow bird universes. Alright, we had a few precious bird observatories just around the corner but how did my peers develop into the generation of observers that made bird identification a particular British skill?

The answer is that at least during the formative period of our birdwatching, many of us had to make our identifications of birds with only them to help us. We had a still-classic tome in the Handbook and some precious notes in BB, but to gain knowledge, to build confidence and to secure new criteria, some of us had to be adventurous first, and careful second.

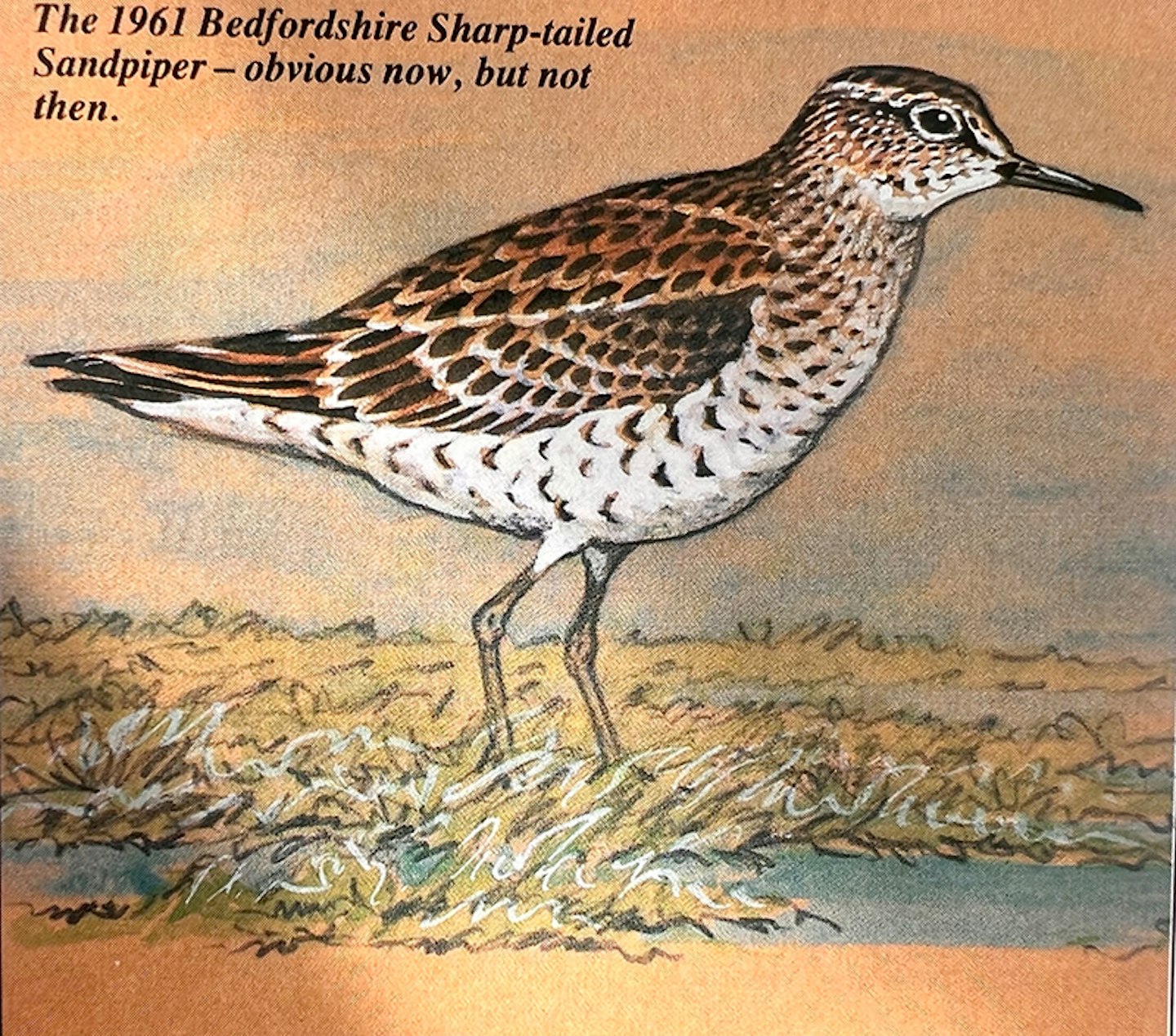

In early September 1961, James Ferguson-Lees invited me to Bedford with the promise of a Norfolk jaunt and a look at a “slightly odd” Pectoral Sandpiper on the way. We took an afternoon stroll to a nearby flooded field. The bird was there, undoubtedly a ‘Pec’ of sorts but unlike my four British and several score Canadian birds. With accelerating heart beats, I noted some dark scallops on its underparts. James looked at me for comment. I took the plunge: “I can’t see it as an American” “I was hoping you’d say that,” he said, “let’s work it over”.

Out came sketch and note book and after an hour of slow stalking, we had nearly every feather – and a distinctive call – described. We retreated to the BB library, drew breath and tried to fulfil the promise that the bird offered of being Britain’s sixth Siberian Pectoral Sandpiper, and only the second in the 20th Century. It was no task for the faint-hearted!

The Roland Green plates in the Handbook were not that helpful. Expecting a first autumn bird, we did not plump for a summer adult. Our bird was not that scalloped anyway, and some Americans had flank marks in any case. Worse still, the field character and voice texts of the Siberian, were only 12 lines long.

Our bird’s lack of gorget was a correct absence, but supporting detail and a clear call difference, we could not find. “Come on, James” , I ventured, “let’s check every feather tract with the detailed description.” “Alright”, he replied, “it seems the only hope.” The treks and crosses that we made are still on pp.264 and 265 of my volume IV (never out of the car in those almost guide-less years) and our analysis still sparkles at me.

It was not a juvenile Siberian but no less than 11 characters fitted its all-age feather patterns, and a further nine fitted its breeding plumage. There were four remaining puzzles, probably due to wear and moult.

Were we safe home? I was sure, but James, always more cautious (and with a higher wanted more proof. Ornithological perch to fall in, “Hang on”, he ordered, “we must read the note on the 1956 Lanark bird”. He leapt to the requisite volume; our heads went down again.

Alas, the Scottish bird had worn a different plumage but reading on, we came at last on the clinching feature. It and our bird had uttered the same call, a pleasant note recalling Swallow and nothing like the reedy grunt of an American.

At long last, James face lit up. We had a lifer. God bless the schoolboy finder, whose name, sadly, I have not recorded. Today the Shorebirds plate and text would have got James and me (or you) to Sharp-tailed, as the Siberian Pectoral is now called, within a minute, but the use of such easy references would have taught us much less. For perception, you really have to struggle.

The moral in all this is simple. Use the amazing modern identification literature by all means, but do not ignore its precedents in the older books and papers and in the full practice of personal observation. Always use your eyes – and the mind and memory just behind them – more on the birds than on the books. Do not delegate the responsibility of any identification.

If you have a tendency to be adventurous, consider whether or not your visual acuity should not be tempered by the presence of a “cautious James” . Help is allowed, but the final conviction must be your own!

Surviving a rejection

It is likely that I have suffered more record rejections than any other British observer. After my comprehensive and public defeat by a Bonelli’s Warber on St Agnes in October 1971, I lost enough face to impoverish China and was pronounced as fallible as, if not more so than, any other observer!

The rejection rate of my claims climbed steeply. Following a series of increasingly fierce fights with the British Birds Rarities Committee, I had no choice but to resign from it. When Tim Sharrock advised me to suspend entirely my apostleship of adventurous, risky – some would say stringy – observations, it took me only a little time to bow out completely.

Thus the 1980s have for me been largely free of rarities, identification disputes and their politics, and I have been able (slowly) to assemble a philosophical attitude to the personal misfortunes in bird identification.

I accept – indeed in the past I often had to propose – the point that all review committees make about rejections. This is, essentially, that most are only not to be taken personally. The fact remains, however, that such platitudes avail a perceptive observer, who becomes certain of a personal advance in skill and knowledge, nothing but enormous frustration in the past, present and – if he is trying to add to the identification literature – future as well.

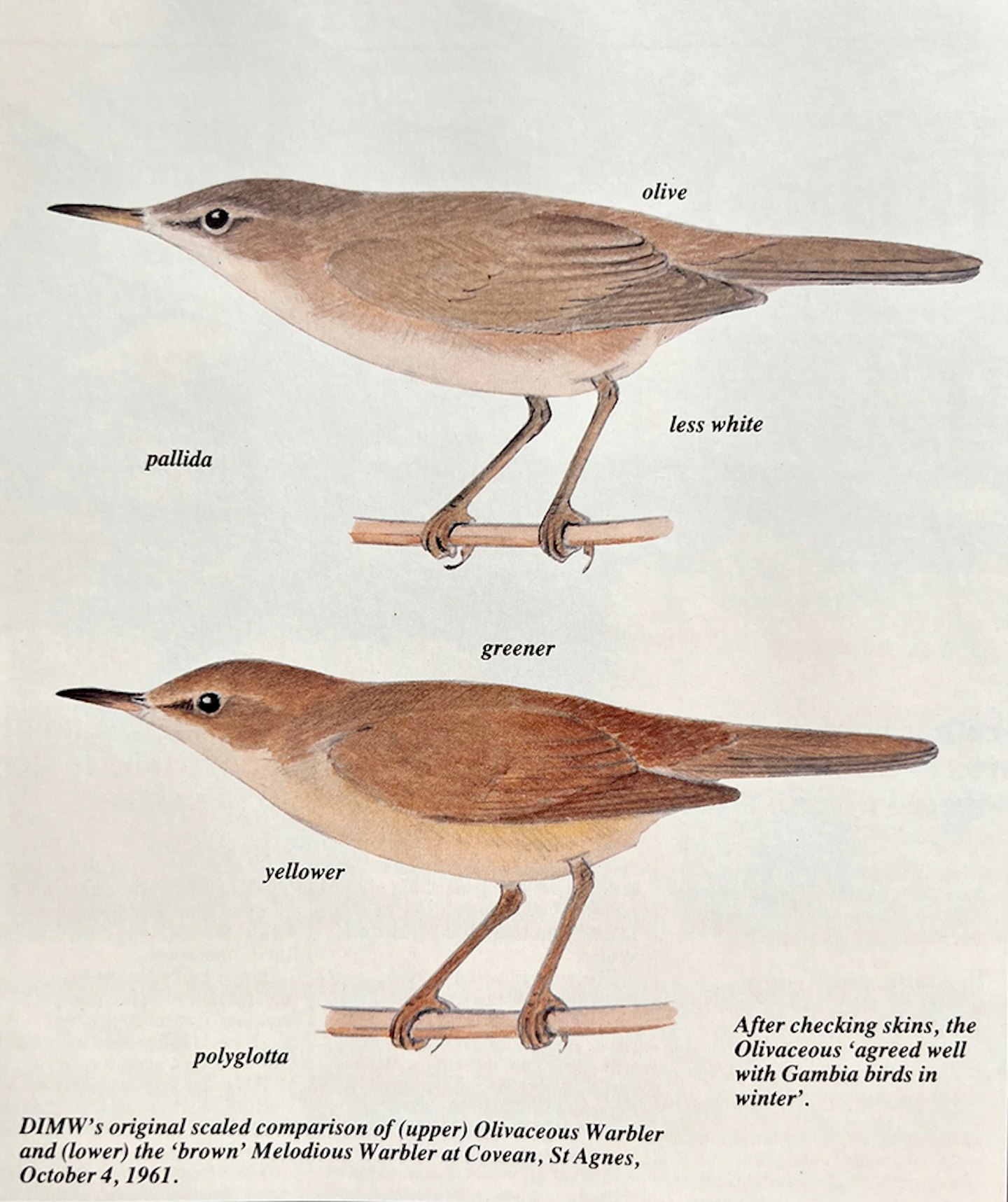

For those of you who have tasted ashes or may yet do so, another tale from 1961 may help. Early October on St Agnes produced lots of rain, down to the last corporate pair of socks, and two truly crippling warblers. From the 1st to the 8th, we saw short-winged Hippolais every day; on the 3rd and 4th, the (then) huge tamarisk clump in Covean was host to two dull birds.

Bob Emmett, Peter Colston, Karin and I spent most of the few dry spells on them. Peering into the green sprays, we became sure of a “brown” Melodious but could not feel anything but disturbing pulses of adrenalin about a paler, more olive bird which sported a real ‘broom-handle’ of a bill. Could it be Britain’s sixth Olivaceous? We felt so, but had no way to prove it, without fuller references and a look at skins.

“It is likely that I have suffered more record rejections than any other British observer, but the 1980s have for me been largely free of rarities, identification disputes and their politics”

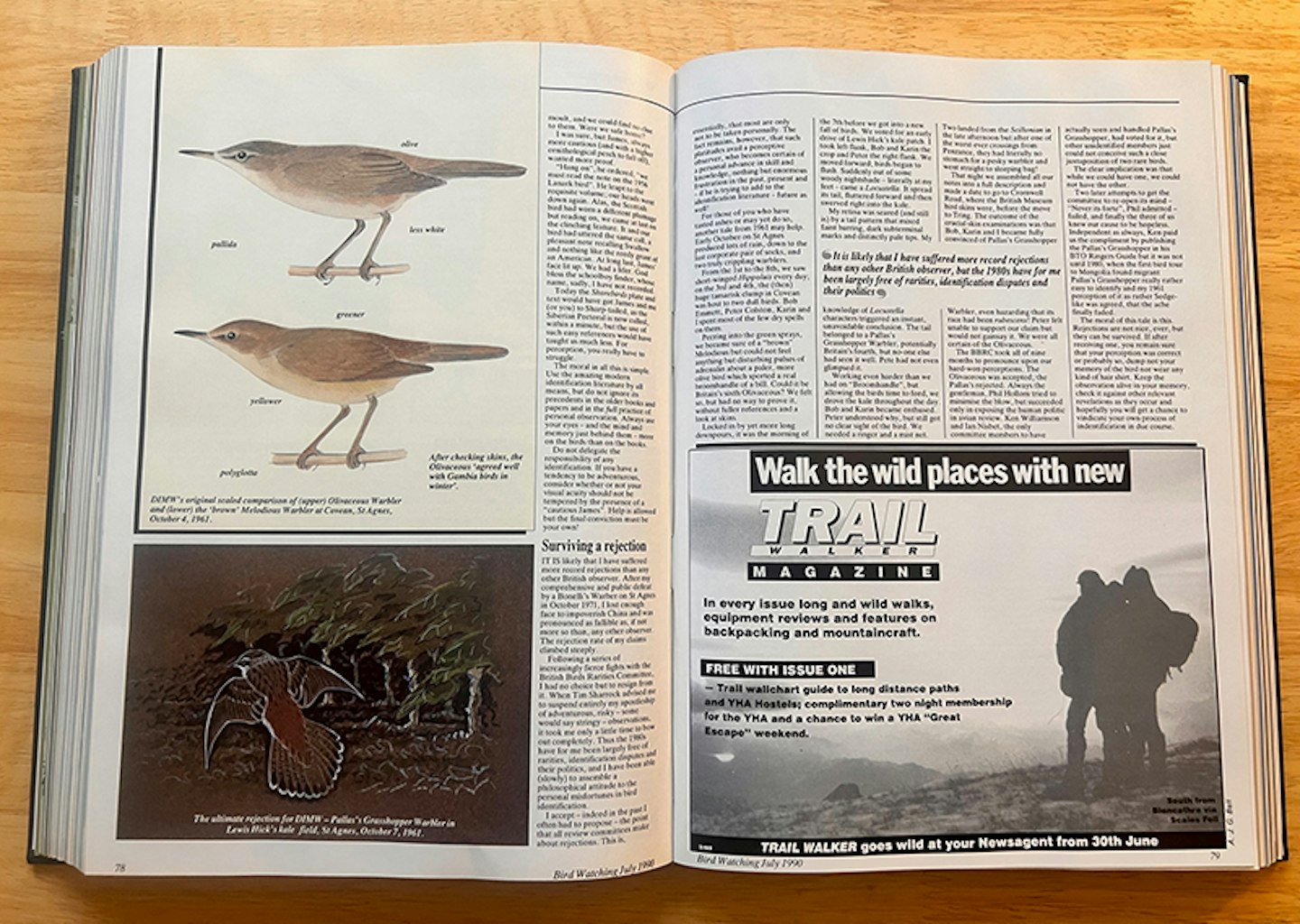

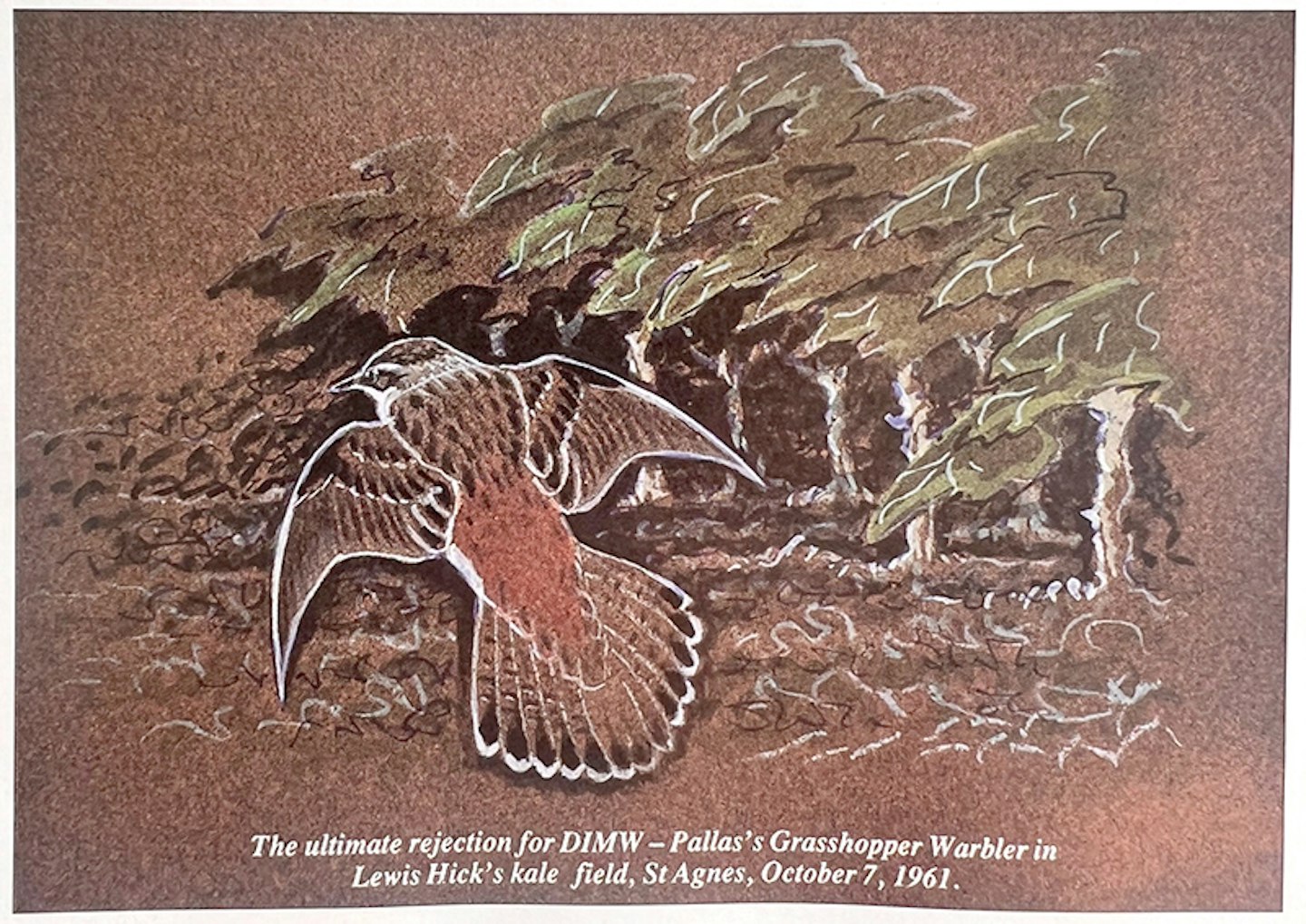

Locked in by yet more long downpours, it was the morning of the 7th before we got into a new fall of birds. We voted for an early drive of Lewis Hick’s kale patch. I took left flank, Bob and Karin the crop and Peter the right flank. We moved forward; birds began to flush.

Suddenly out of some Woody Nightshade – literally at my feet – came a Locustella. It spread its tail, fluttered forward and then swerved right into the kale. My retina was seared (and still is) by a tail pattern that mixed faint barring, dark subterminal marks and distinctly pale tips. My knowledge of Locustella characters triggered an instant, unavoidable conclusion.

The tail belonged to a Pallas’s Grasshopper Warbler, potentially Britain’s fourth, but no-one else had seen it well. Pete had not even glimpsed it. Working even harder than we had on ‘Broom-handle’ but allowing the birds time to feed, we drove the kale throughout the day. Bob and Karin became enthused. Peter understood why, but still got no clear sight of the bird. We needed a ringer and a mist net.

Two landed from the Scillonian in the late afternoon but after one of the worst-ever crossings from Penzance, they had literally no stomach for a pesky warbler and went straight to sleeping bag! That night we assembled all our notes into a full description and made a date to go to Cromwell Road, where the British Museum bird skins were, before the move to Tring.

The outcome of the crucial skin examinations was that Bob, Karin and I became fully convinced of Pallas’s Grasshopper Warbler, even hazarding that its race had been rubescens! Peter felt unable to support our claim but would not gainsay it. We were all certain of the Olivaceous.

The BBRC took all of nine months to pronounce upon our hard-won perceptions. The Olivaceous was accepted; the Pallas’s rejected.

Always the gentleman, Phil Hollom tried to minimise the blow, but succeeded only in exposing the human politic in avian review. Ken Williamson and Ian Nisbet, the only committee members to have actually seen and handled Pallas’s Grasshopper, had voted for it, but other unidentified members just could not conceive such a close juxtaposition of two rare birds. The clear implication was that while we could have one, we could not have the other.

Two later attempts to get the committee to re-open its mind – “Never its forte” Phil admitted – failed, and finally the three of us knew our cause to be hopeless. Independent as always, Ken paid us the compliment by publishing the Pallas’s Grasshopper in his BTO Ringers Guide, but it was not until 1980, when the first bird tour to Mongolia found migrant Pallas’s Grasshopper really rather easy to identify and my 1961 perception of it as rather Sedge-like was agreed, that the ache finally faded.

The moral of this tale is this. Rejections are not nice, ever, but they can be survived. If after receiving one, you remain sure that your perception was correct or probably so, dump not your memory of the bird nor wear any kind of hair shirt. Keep the observation alive in your memory, check it against other relevant revelations as they occur and hopefully you will get a chance to vindicate your own process of identification in due course.