Paperwork brings eventual pleasure

June 1990

Ordinary birdwatchers may think they would never be able to get their observations into print, but everyone has to start somewhere. Ian Wallace gives useful advice on getting your work accepted.

Last month I told you of birdwatching lessons in the 1940s and 1950s and preached about working a patch and building a case. This month, I turn to writing, but what I want to provoke is not “nut and bolt” entries in diaries, but your serious attempt at ornithological authorship.

Many birders are shy of putting disciplined pen to scientific paper. I well remember trying to coax Dave Holman (one of the first generation of Scilly twitchers) into the task. Initially shunning it, he said of himself and his peers: “We’re illiterates; we wouldn’t know where to start”. They most certainly were not and he in particular did start, becoming eventually, an expert member of the British Birds Rarities Committee.

My own first serious publication was a BB Note on the 1949 Lesser Yellowlegs, whose tale I told in the first of my ‘Those Were The Days’ series. How did I write it? By following the note-writing instructions then published in BB every month and by checking the result against the models of established BB correspondents.

I was appalled by the number of words that the then Editor JD Wood wanted cut from my peerless prose, but a third revision passed muster. Amazingly, my name would appear in the national bird journal. My stock at school rose slightly; I was rather pleased (understatement).

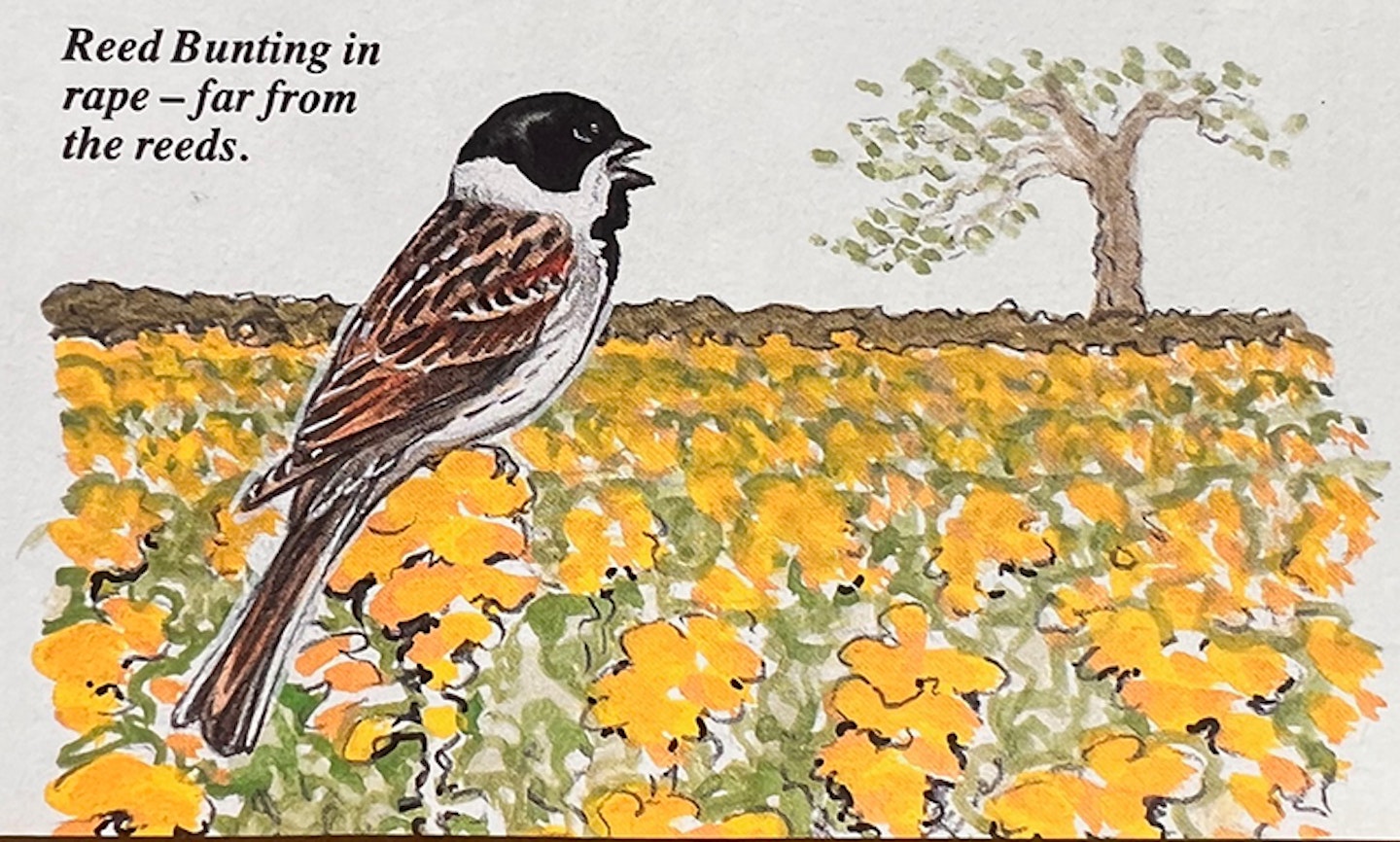

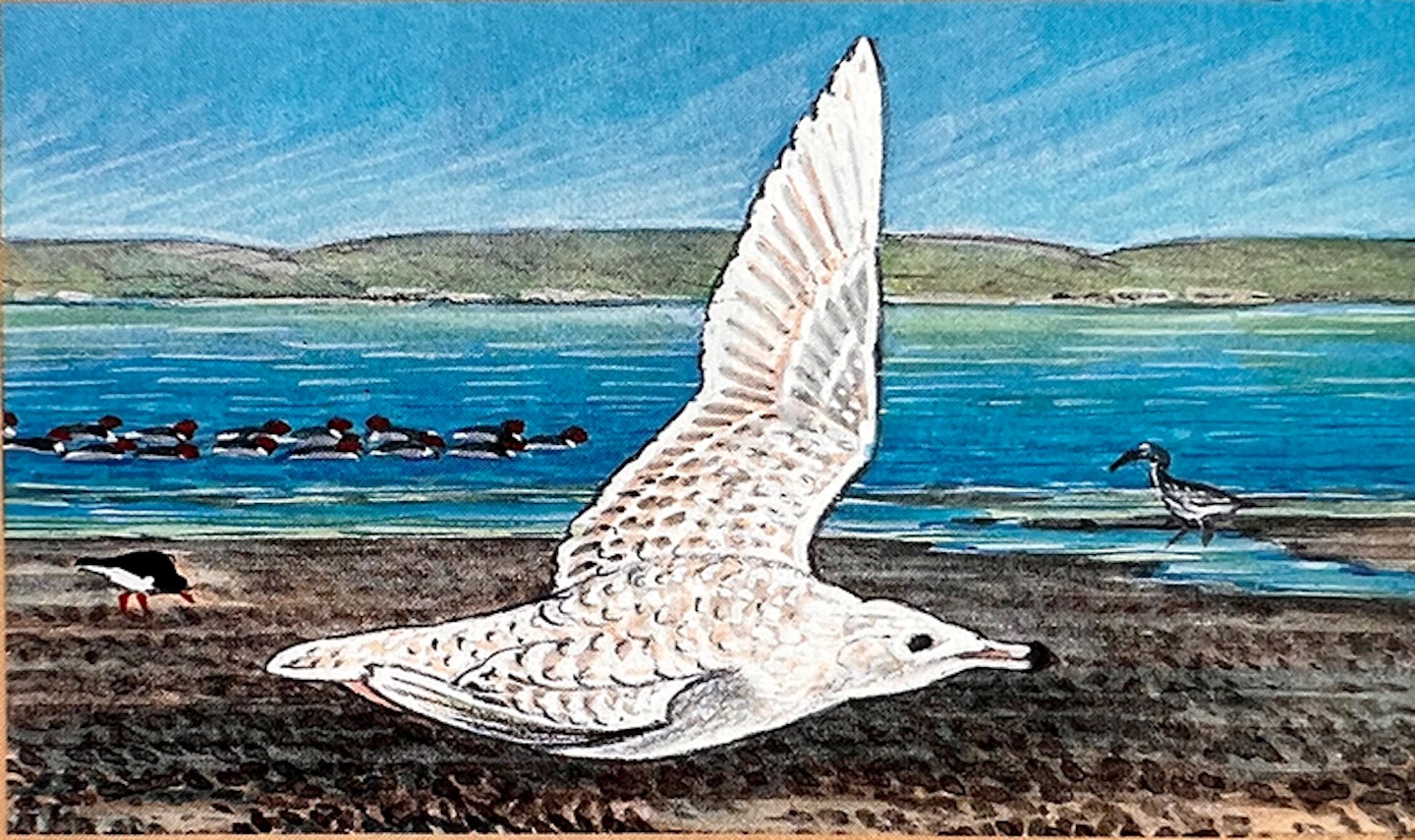

My second serious contribution would be laughable nowadays. One June morning in 1950, I was far out on the mussel beds of Musselburgh looking at the flock of non-breeding Red-breasted Mergansers that summered off the mouth of the River Esk. Suddenly, head on into my binocular view, flew an enormous, pale, biscuit-coloured gull.

Used to mobbing Bonxies in my early Shetland summers, I stood my ground. Seemingly oblivious of my presence, the brute pushed its huge, pink-based, dark-tipped beak past me and went on down the Firth of Forth. Faintly marked overall, it was no albino, and with the help of schoolmaster Eek Turner, I identified it as an immature Glaucous Gull.

“I can find no precedent for a June record”, mused Eek augustly, “it would seem to require another note in BB”. So, back to the desk and out with the instructions again. Establish when, where; say what species (complete with Latin name) and what act; explain why the event was unusual. I romped through the exercise and made a silly mistake. Instead of putting “immature” in front of Glaucous Gull, I wrote “mid-summer”.

Uncharacteristically, Mr Wood did not spot the misplacement and it irks me still that my haste spoilt the full sense of the piece. In 1954, a chance meeting on Fair Isle with the next editor of BB, James Ferguson-Lees, drew me into a period of most excellent instruction in ornithological writing. If, at times, wayward in keeping BB to time, James’ editorship has never been surpassed for stylish discipline and the development of new authors. I became a willing apprentice and what James called “BB’s odd job man” for 15 years.

Thought by some rather stand-offish, James actually allowed more than a little humour into BB’s pages and I owe him my favourite Note, the story of how an enraged Nightingale so angrily ‘swore’ at my Cairn Terrier that the latter retreated tail-down at pace. Alas, such an incident would not get space in Birding World [now defunct monthly journal specialising in rare birds and ID]. Well I suppose it might if the swearer was a Thrush Nightingale!

The most prolific author of scientific notes in my ornithological lifetime was the late rubicund and gentle Bernard King. He became a BB centurion and his wide range of subjects still presents both many models to emergent writers and repeated proofs that amateurs can regularly contribute to science.

When it came to full-length, tightly-argued papers, there was an equally outstanding amateur author. This was the amazing Ian (Dr ICT) Nisbet, whose ornithological and other intellect was quite exceptional. Without doubt, he was the Young Turk of the 1950s and early 1960s, writing regularly not only for BB but also for the more austere Ibis, the journal of the British Ornithologists’ Union.

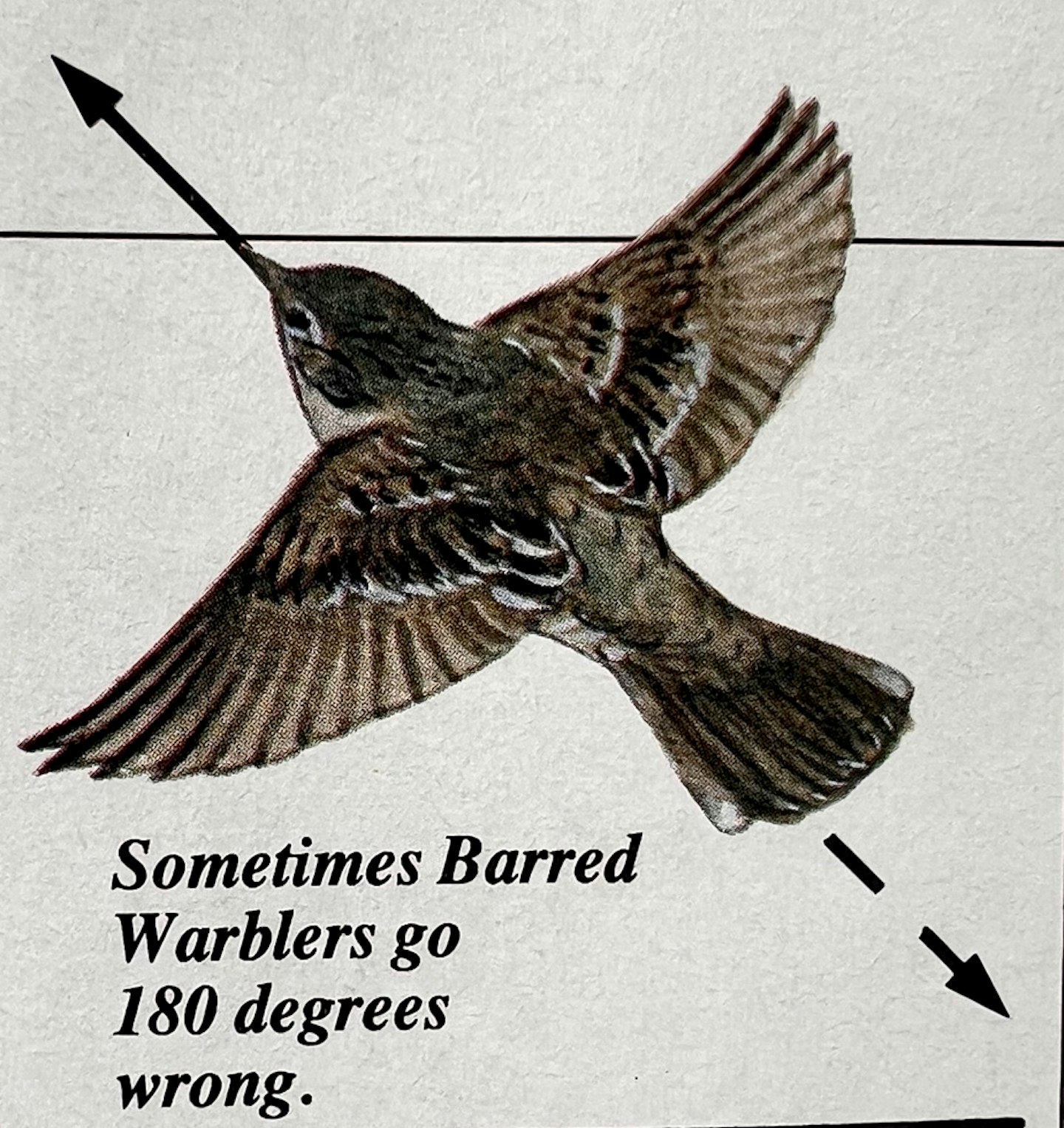

Almost single-handed, lan turned us back from too total an acceptance of “drift” by re-demonstrating “reversed migration” particularly well shown by the Barred Warbler, brought “moon-watching” across the Atlantic – (what you ask?) – staring at the moon until birds cross its face and then using tables to work out their directions and numbers; edited county reports and much more, in a bravura performance which he continues still in Nearctic bird conservation.

Writing a Note

You are out after birds. Something unusual turns up or happens. You will submit notes to your local recorder, but does it merit separate publication?

There is only one way to answer this question. You have to check the existing literature. If you have several years behind you in birdwatching, you may already have an inkling but if you are a beginner, you will face a fairly hefty read.

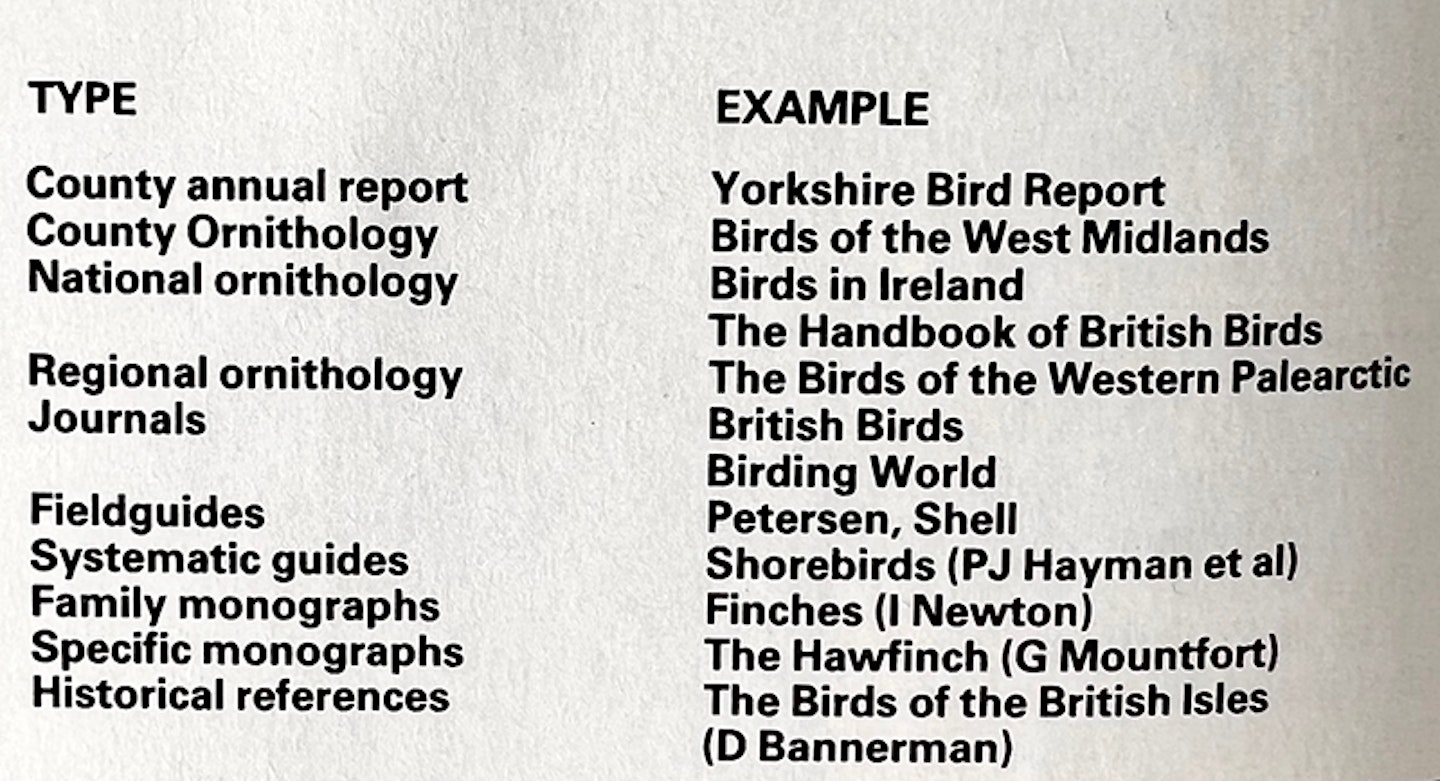

Forty years ago, ‘the Handbook’ was only a decade old. A look at its texts and the intervening BB indexes could produce judgments on real news fairly promptly. In 1990, the ornithological annals that have to be searched are extensive. A short list follows:

Access to all of the above, or necessary alternatives, may not be easy. So, consult your local ‘trained soldier’ or your local town library and museum. In the last resort, write for advice from the officers or editors of the institutions. Polite enthusiastic enquiries still get helpful answers.

Let us assume that your unusual avian event has stayed so. It does indeed merit publication. How do you write about it? I mentioned many models earlier and your literature search will have shown you others. For a first time, there will be no shame in copying the order of contents of other authors and it will help the editor of the report or journal if he does not see an immediate task of re-writing or precis. With costly space often a consideration, do not be tempted into too much purple prose, but a little bit to keep the humanities overt is usually allowed.

There is no absolute rule on length – 40-80 words for a short, factual statement, 200-350 for some development of a subject and up to 1,500 for complex discussion with illustration. Many more than 1,500 words and you will be writing a short Paper.

Again, there is no strict rule on content order but it makes sense to have a pithy title and get straight to the main point of your observation. If you are writing about a single bird, then a phrase fixing date/locality/species is the classic opening. This gives the subject a fixed station in time and place and you can lead directly into what it did or looked like.

Finish the description of your bird or event before setting it in further context, by mentioning other similar observations or emphasising its singularity. Never forget to give precise references to the notes and papers of other authors that you use in your text.

If you are making a general point, stations of time and place may not be relevant at the start, but there will always be a main theme that needs highlighting and can be later supported by full observations or discussed through references.

There is one final hurdle. Nowadays, notes are reviewed not only by editors but also by expert referees or panels of such. It may be that they will not see your discovery as significant (and so decide against its publication) or as insufficiently significant to warrant its proposed length (and so ask for its shortening). You must accept their decision. Try not to be put off by it and always resolve to do better!

Writing a Paper

Expanding your authorship from a Note to a Paper is a big step. In the former, you are usually making one statement about one or relatively few observations; in the latter, you are usually pronouncing upon several third party statements while trying to make yours the most expert or apposite yet. So, a Paper means much more personal responsibility in research analysis, judgment and conclusion.

It is never a task to rush, but its completion will give you an enormous sense of achievement, once in print. It took 15 years (and Ken Williamson’s nudge) for me

to produce my first, but there have been more flying starts.

Unlike a Note, a Paper requires the construction of a lengthy statement in a sequence that allows easy understanding of its theme(s), and so attracts readership. Thus you must plan a Paper much more fully than you do a Note and establish a basic rhythm of presentation in which your words carry the reader forward to your conclusion.

The headings of a paper’s sections vary according to subject but the following common components are usually visible:

(1) introduction,

(2) development of and supporting evidence for main theme,

(3) development of references to subsidiary points,

(4) discussion and/or resolution of contrary views,

(5) suggestions for further research,

(6) conclusion,

(7) summary,

(8) acknowledgments of assistance,

-

bibliographical references, and

-

Author’s name and address.

It makes sense to use such a skeletal discipline, sketch in where your new facts will be announced and old ones discussed, where your perception of them differs from those of others or adds new dimensions and whether your conclusion is complete or tentative. As you write the full text, the last point is crucial. As a new author, do not claim too much, however fast your heart beats. Editors, and these days, many skilled observers will pounce on anything like careless conceit.

Since identification is the prime interest of most current observers, let me sketch in more fully the proving of a new field character.

The acts are:

(1) your perception of one,

(2) research into recent statements on the species to make sure that it is worth pursuing, (3) search for other support for the character, eg in photographs,

(4) examination of skins further to prove the character,

(5) offer of the character for expert criticism,

(6) clear written exposition of the character,

(7) addition of drawings or photographs,

(8) patience with the final edit and

(9) willingness to follow up post-publication criticism of the character.

No, it is not an easy process, but complete it and you will have perceived something that no one else has. Not too many human beings do that.

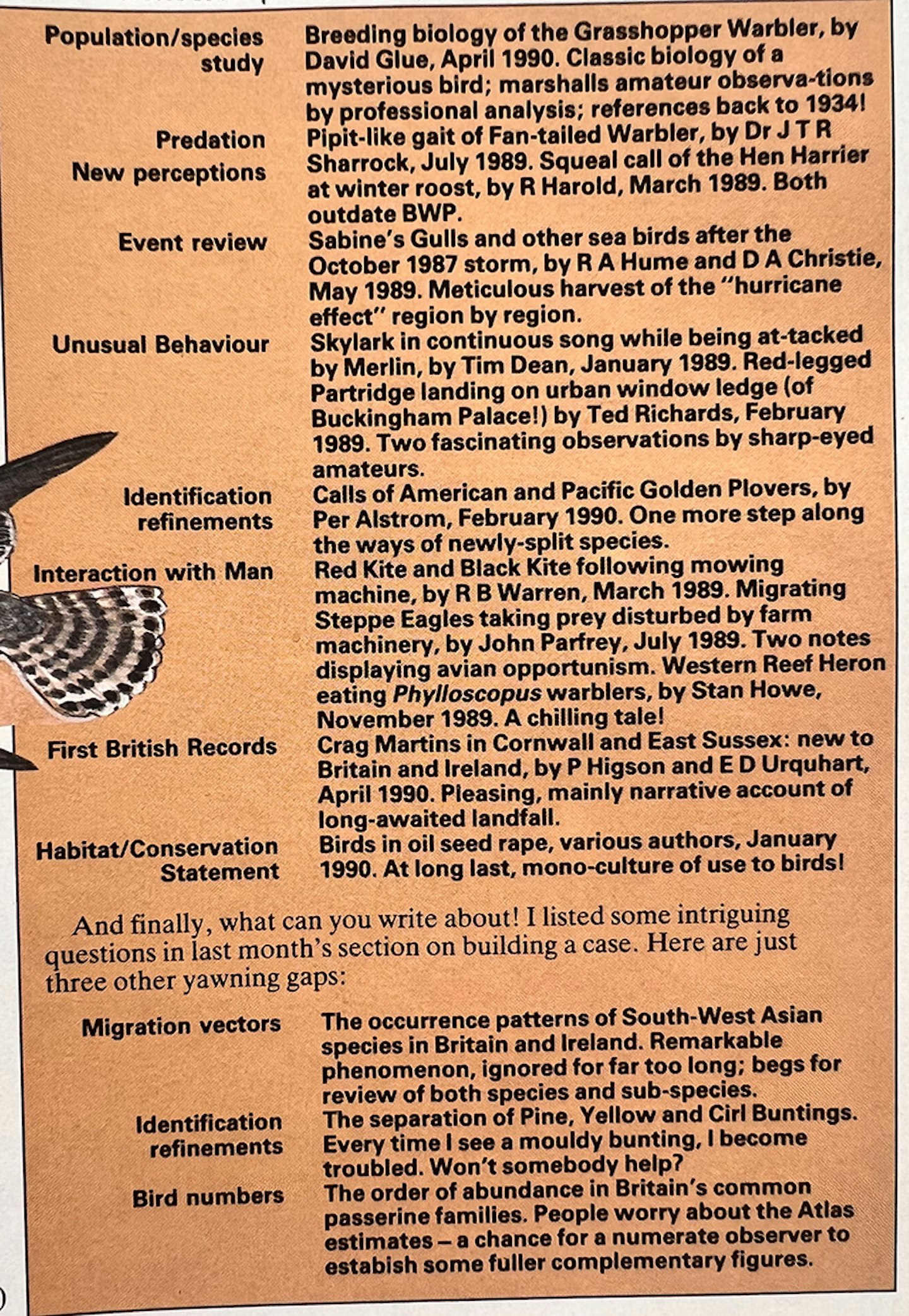

To give you more guidance on broad church writing, I have looked at the recent issues of BB and picked out for you some more models of Notes and Papers:

All a bit daunting? Well, as my generation demonstrated - and if we are not to see the Swedes take over yet more of our former predominance in the amateur literature - writing needs constantly new hands with pens. So many of you have learned so much faster than us. So live up to your past and go for it!