Leg-breaker… heart-stopper

March 1990

In two March tales, Ian Wallace contrasts a cold chase after an American wader – with only a close friend for company – and an eventually blissful meeting with an Arctic gull – with a crowd of fellow-tickers as loud chorus.

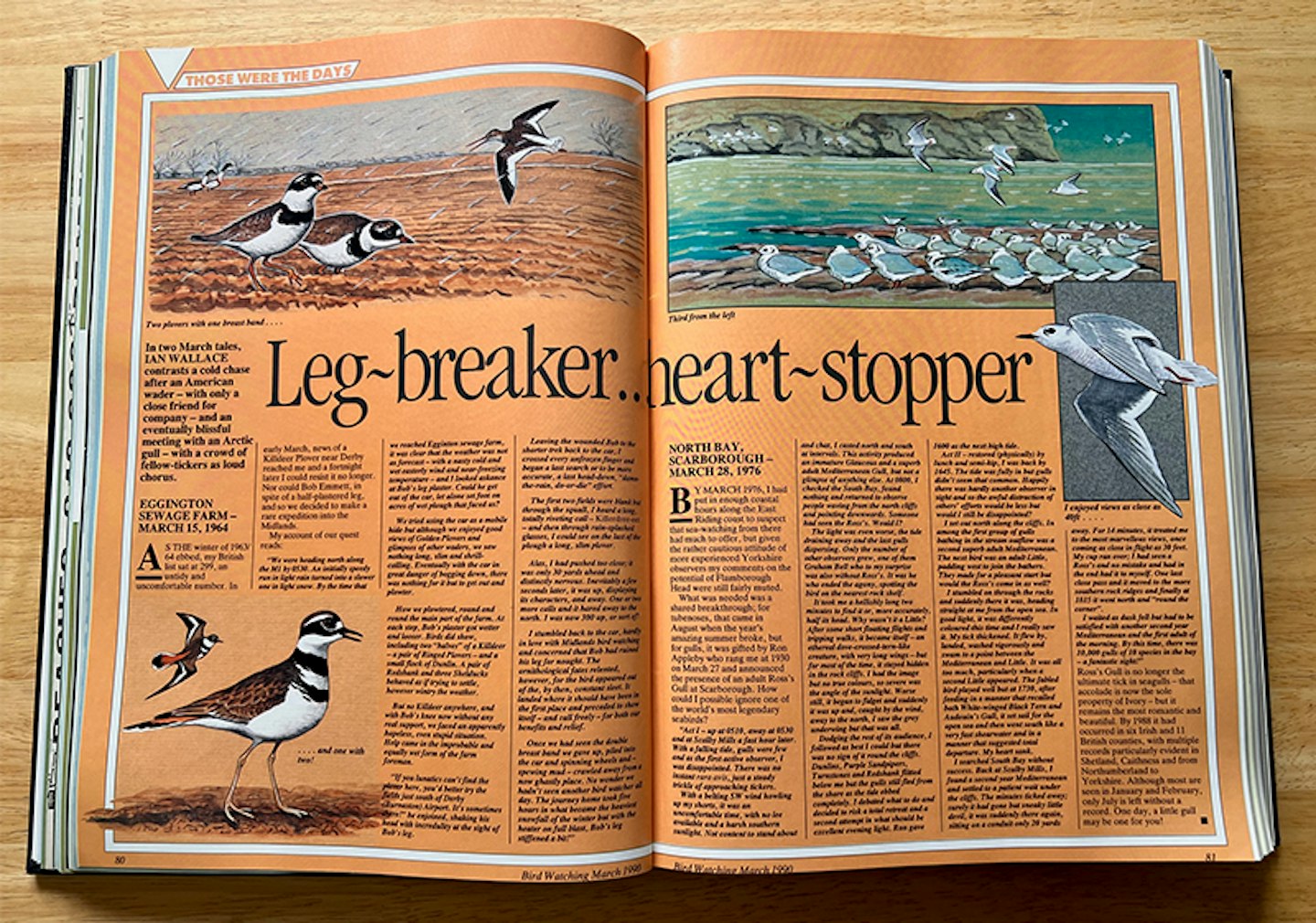

EGGINGTON SEWAGE FARM – 15 MARCH 1964

As the winter of 1963/64 ebbed, my British list sat at 299, an untidy and uncomfortable number. In early March, news of a Killdeer near Derby reached me, and a fortnight later I could resist it no longer. Nor could Bob Emmett, In spite of a half-plastered leg, and so we decided to make a rare expedition into the Midlands.

My account of our quest reads:

We were heading north along the M1 by 0530. An initially speedy run in light rain turned into a slower one in light snow. By the time that we reached Egginton sewage farm, it was clear that the weather was not as forecast – with a nasty cold and wet easterly wind and near-freezing temperature – and I looked askance at Bob’s leg plaster. Could he get out of the car, let alone set foot on acres of wet plough that faced us?

We tried using the car as a mobile hide but although we enjoyed good views of Golden Plovers and glimpses of other waders, we saw nothing long, slim and shrill-calling. Eventually with the car in great danger of bogging down, there was nothing for it but to get out and plowter. How we plowtered, round and round the main part of the farm. At each step, Bob’s plaster got wetter and looser.

Birds did show, including two “halves” of a Killdeer – a pair of Ringed Plovers – and a small flock of Dunlin. A pair of Redshank and three Shelducks behaved as if trying to settle, however wintry the weather. But no Killdeer anywhere, and with Bob’s knee now without any real support, we faced an apparently hopeless, even stupid situation. Help came in the improbable and equally wet form of the farm foreman.

“If you lunatics can’t find the plover here, you’d better try the fields just south of Derby (Burnaston) Airport. It’s sometimes there!” he enjoined, shaking his head with incredulity at the sight of Bob’s leg.

Leaving the wounded Bob to the shorter trek back to the car, I crossed every unfrozen finger and began a last search or to be more accurate, a last head-down, “damn-the-rain, do-or-die” effort. The first two fields were blank, but through the squall, I heard a long, totally riveting call – ‘Killerdree-eet’ – and then through rain-splashed glasses, I could see on the last of the plough a long, slim plover.

Alas, I had pushed too close; it was only 30 yards ahead and distinctly nervous. Inevitably, a few seconds later, it was up, displaying its characters, and away. One or two more calls and it hared away to the north.

I was now 300 up, or sort of!

I stumbled back to the car, hardly in love with Midlands birdwatching and concerned that Bob had ruined his leg for nought. The ornithological fates relented, however, for the bird appeared out of the, by then, constant sleet. It landed where it should have been in the first place and preceded to show itself – and call freely – for both our benefits and relief.

Once we had seen the double breast band we gave up, piled into the car and spinning wheels and spewing mud – crawled away from a now ghastly place. No wonder we hadn’t seen another birdwatcher all day. The journey home took five hours in what became the heaviest snowfall of the winter, but with the heater on full blast, Bob’s leg stiffened a bit!”‘

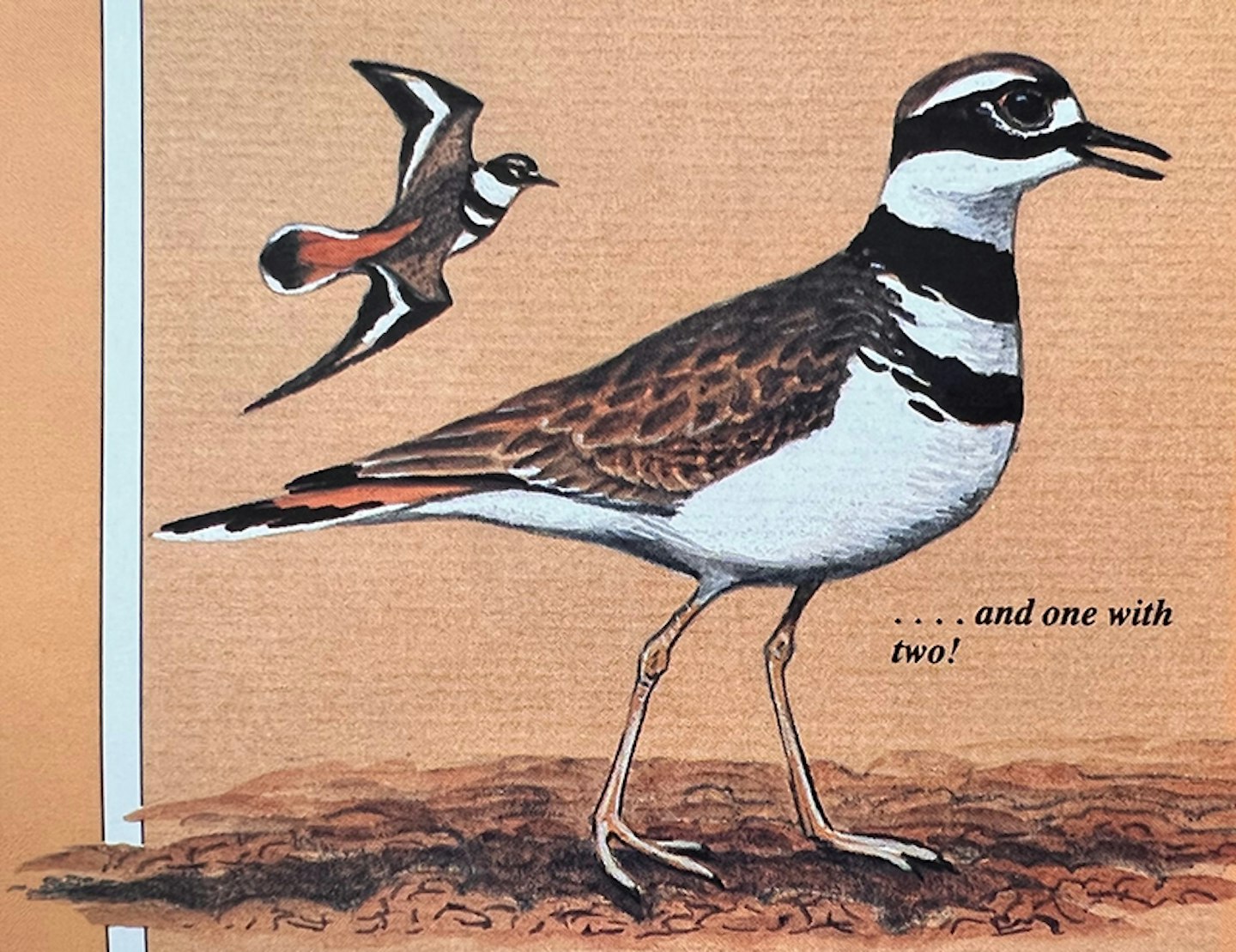

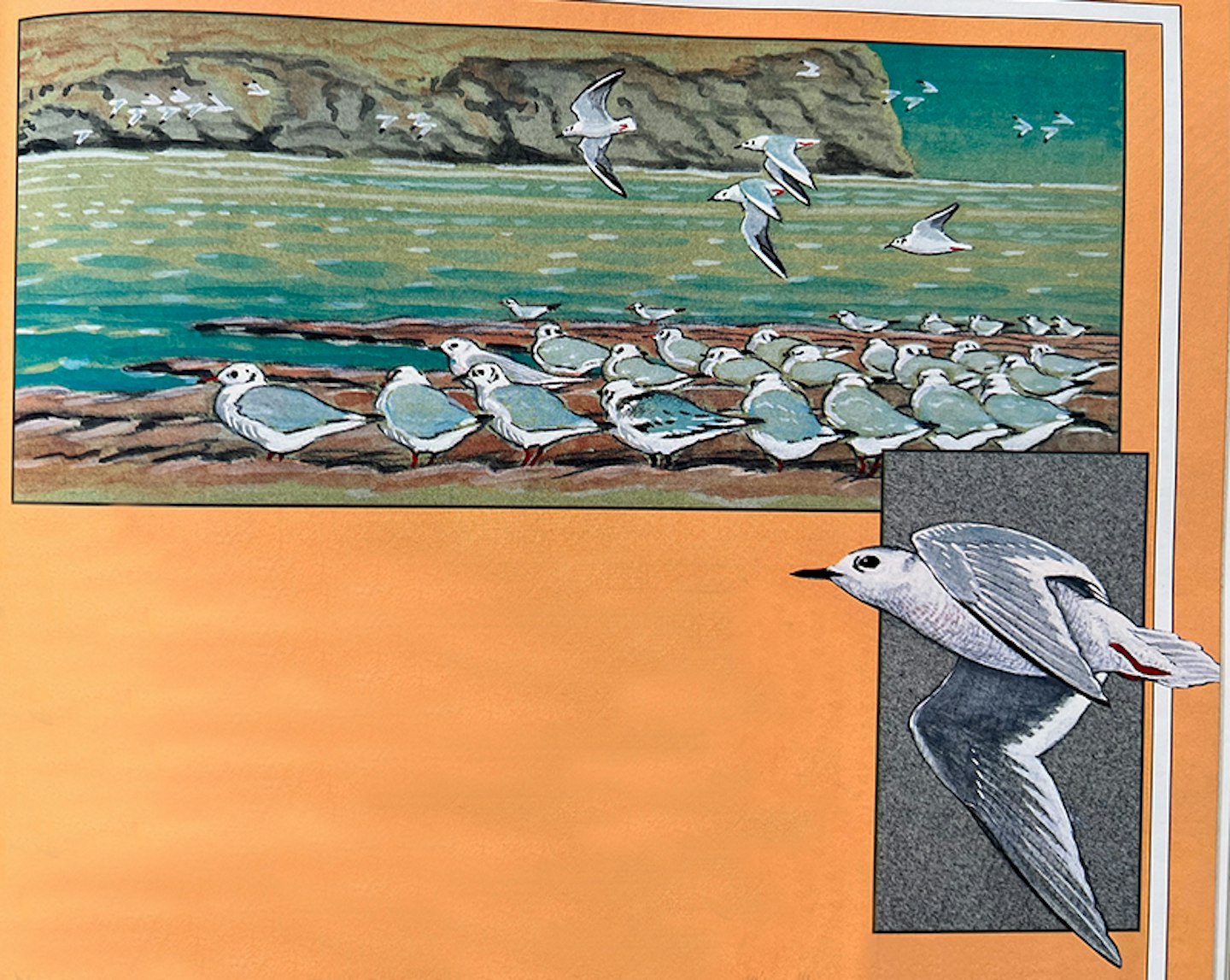

NORTH BAY SCARBOROUGH – 28 MARCH, 1976

By March 1976, I had put in enough coastal hours along the East Riding coast to suspect that seawatching from there had much to offer, but given the rather cautious attitude of more experienced Yorkshire observers, my comments on the potential of Flamborough Head were still fairly muted.

What was needed was a shared breakthrough; not for tubenoses, that came in August when the year’s amazing summer broke, but for gulls. It was gifted by Ron Appleby who rang me at 1930 on 27 March and announced the presence of an adult Ross’s Gull at Scarborough.

How could I possible ignore one of the world’s most legendary seabirds?

Act I – up at 0510, away at 0530 and at Scalby Mills a fast hour later.

With a falling tide, gulls were few and as the first active observer, I was disappointed. There was no instant rara avis, just a steady trickle of approaching tickers. With a belting SW wind howling up my shorts, it was an uncomfortable time, with no lee available and a harsh southern sunlight. Not content to stand about 1600 as the next high tide.

Act II – restored (physically) by lunch and semi-kip, I was back by 1645.

The tide was fully in but gulls didn’t seem that common. Happily there was hardly another observer in sight and so the awful distraction of others’ efforts would be less but would I still be disappointed?

I set out north along the cliffs. In among the first group of gulls bathing in the stream outflow was a second superb adult Mediterranean. The next bird was an adult Little, padding west to join the bathers. They made for a pleasant start but would the Ross’s come in as well?

I stumbled on through the rocks and suddenly, there it was, heading straight at me from the open sea. In good light, it was differently coloured this time and I really saw it. My tick thickened. It flew by, landed, washed vigorously and swam to a point between the Mediterranean and Little.

It was all too much, particularly when a second Little appeared. The fabled bird played well, but at 1730, after feeding in a manner that recalled both White-winged Black Tern and Audouin’s Gull, it set sail for the open sea and then went south like a very fast shearwater and in a manner that suggested total departure.

My heart sank. I searched South Bay without success. Back at Scalby Mills, I found a second-year Mediterranean and settled to a patient wait under the cliffs. The minutes ticked away; surelv it had gone but, sneaky little devil, it was suddenly there again, sitting on a conduit only 20 yards away.

For 14 minutes, it treated me to the most marvellous views, once coming as close in flight as 30 feet. My cup ran over; I had seen a Ross’s and no mistake and had in the end had it to myself. One last close pass and it moved to the more southern rock ridges and finally at 1815, it went north and ‘round the corner’. I waited as dusk fell but had to be satisfied with another second year Mediterranean and the first adult of the morning.

By this time, there were 10,000 gulls of 10 species in the bay a fantastic sight!” Ross’s Gull is no longer the ultimate tick in seagulls – that accolade is now the sole property of Ivory – but it remains the most romantic and beautiful. By 1988, it had occurred in six Irish and 11 British counties, with multiple records particularly evident in Shetland, Caithness and from Northumberland to Yorkshire. Although most are seen in January and February, only July is left without a record. One day, a little gull may be one for you!