Crossing the Pelican’s path

January 1990

In the late 1960s, twitching became the main syndrome of some birdwatching lives, but there was still no mass commitment to it. Just occasionally, Ian Wallace felt it sensible to take to the overnight road and secure the odd ‘one chance in a lifetime’ bird. Here is what happened on one such foray.

When the late Kenneth Allsopp decided to feature the then new phenomenon of twitching on BBC Radio, I was asked to suggest who should answer his questions. There was only one real candidate, the amazing, fast Saab-driving Ron Johns who was already intent on being the first observer to see 400 wild bird species in Britain.

So it was that Ron, Bob Emmett and I duly attended Broadcasting House and the all-out pursuit of rarity after rarity got its first somewhat bantering airtime. Little did we think that 20 years on, rare birds would regularly be given space in the national news and one Norfolk café’s telephone would change into several bulletins of almost every day’s avian events.

To know Ron Johns in the 1960s was to be as close to the grapevine as possible, and now and again Bob, who was in regular touch with him, would ring up and dangle a plum bird in front of me. I did not go for such targets as often as hearsay has it, but when offered in one place: a Dalmatian Pelican, a family of Serins and wintering Blackcaps and Firecrests, I took the bait.

Hayle, St Ives and Land’s End, 6 January 1968

Bob and Ron came down the night before and we spent several hours in Scilly reminiscences before sleep. This ended at 0400hrs, and 35 minutes later, we left Eastcombe (in the Cotswolds) for our main goal, the Hayle Estuary (in west Cornwall), The night was wet and wild but sharing the driving, we were theer by 0932hrs (not bad on the old roads!). My log reads:

Looking over the wall, we quickly saw that the only large white birds visible in the distance were Mute Swans. Slight panic set in. A wider and closer cast produced a strange, dirty white, anvil-shaped blob on the nearby rocks at the end of the main channel. Re-sorting its parts, the blob proved to be a sleeping pelican, minus a beak (which was stuck below its back feathers).

Using the wall as cover, we got a better light angle on it and confirmed that it was the Dalmatian. I thought it a bit tame to be sleeping so close to human traffic but then the tide was in. Perhaps later it would go further away and look wilder! With the day’s main target instantly secured, we breakfasted and discussed tactics. A gale was coming in, said the weather forecast, and so obviously we would have to try for the Serins next. “Look on the rubbish tip at Lelant”, were our instructions and so the best ploy appeared to be a low wander round the estuary’s edge, taking in its massed wildfowl on the way.

It worked and in the next three hours we enjoyed the Havle estuary as never before. Of more than 1,000 duck, Wigeon were the commonest, but the real surprises were two Gadwall and a Pintail. In the mud gutters, rails numbered only 11 but seven of these were Water Rails, giving the most open feeding performance that any of us had ever seen – behaving like waders! Of the last group, ten species showed but we failed to find anything odd among them.

"In the mud gutters, ‘rails’ numbered 11. but seven of these were Water Rails, giving the most open feeding performance that any of us had ever seen."

What impressed more was the number of passerines scattered along the drier, weedy sectors of the estuary edges. Four finches were interspersed with Meadow Pipits and Wagtails. In the odd bushes, we found not only Goldcrests but also a Chiffchaff. The magic of the far South-West was fully present. At the newly flattened rubbish tip, we spread out to find our next targets, four Serins. Like the Pelican, they led us no dance and soon we had them virtually at our feet, twinkling in and out of Linnets, Chaffinches and bustling Starlings.

The one that I saw best was a dull first-winter bird, but Ron and Bob saw two bright adults well. All four birds had winking lemon-yellow rumps that made them easy to follow through the Linnet swarm. Eventually, they went into the sanctuary of the treed gardens behind. We peered in but did not see them, nor the Blackcaps and Firecrests also reported to be there. Mind you, by this time, large raindrops were hurtling through the wet air. So, we beat a full retreat to the car and more food.

As we restored our fuel reserves, the wind swung suddenly from S to W, the rain became pouring strength and further foot searches were voted out. The midday forecast was appalling. We scrapped all thought of a night in tents and debated how to use the rest of our day best.

Seawatching from the car was the only sensible course, and off we drove for St Ives. There, the sea was already angry and visibility closed down to less than a mile. Even so, we settled down in the lower car park and waited. A Long-tailed Duck struggled west into the gale and next, a superb fully adult Mediterranean Gull came in to inspect the flotsam just offshore. Both unexpected, they cheered us up no end and we peered even harder in the spray and murk.

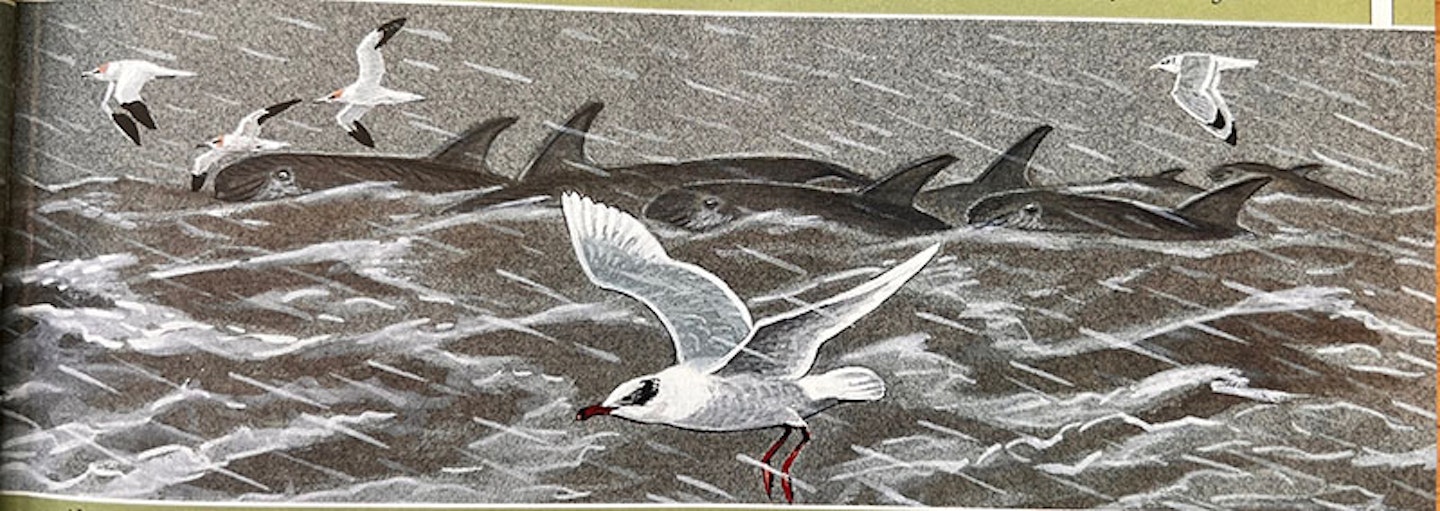

Further out, we could just make out Gannets and Kittiwakes going west but what the devil was happening underneath them? The waves seemed to be exploding or going occasionally in the opposite direction. Then suddenly we saw an explosion of small cetaceans and knew that a stream of them was ploughing across the bay. For once, birds were forgotten as we strained to get enough characters to identify a sea mammal.

Used to Common Dolphins riding the Scillonian’s bow wave, we were puzzled by this lot’s blunt heads, drab colour, larger size and odd back fin shape and position. Party after party passed before us, in all between 150 and 200, and making up the biggest cetacean movement that any of us had ever seen.

As it ended, an adult Little Gull took the place of the Mediterranean ,and three divers, too far off in the murk to be named, hurtled east. Frustrated by the lack of height in our watchpoint, we tried to find better spots to look over the sea. At Land’s End, the beast of the gale so shook the car that using glasses was impossible.

At Sennen Cove, the sea was now furious and only Gannets and Fulmars were making any progress. All gulls and waders were sheltering among the rocks. A few steps out of the car and once again we had to concede defeat. Where could we find some lee to use the day’s last light? We crossed over to Penzance and Newlyn and finding just a little respite from the gale, we worked through the gulls.

Our hopes of a Bonaparte’s were not realised, but we did notch up two Purple Sandpipers and 15 Sanderlings near the swimming pool. So the variety of the day’s birds still grew and we moved on, around Mount’s Bay. A large diver opposite St Michael’s Mount proved to be a Great Northern -when we drove down the wave-splashed slipway at it! – and five duck in the Marazion Marsh turned out to be Shovelers.

A last splashing tramp in a less lash-filled dusk was full of jumping Snipe. The day was over but at least we had made the most of it! The journey home was horrendous, like driving through the Atlantic, but we had much to muse on, particularly the identity of the small cetaceans. In the end, we were all agreed that they were far better value than the Pelican.

Back at Eastcombe, I dug out my mammal books and we worked through the small whales and dolphins. Clearly the beasts that had leapt highest (and best) were Risso’s Dolphins – a lifer mammal for us all – and if they were all that species, their passage had been quite exceptional for even south-west British waters.

As for the Pelican (which had incidentally swum away from the road to feed in the middle channels of the estuary later in the morning), well, we had at worst taken out insurance against it becoming eventually a category A species. As it is, it remains stuck in category D, which means that as a species, it has done something intriguing but not enough to prove a fully natural origin!