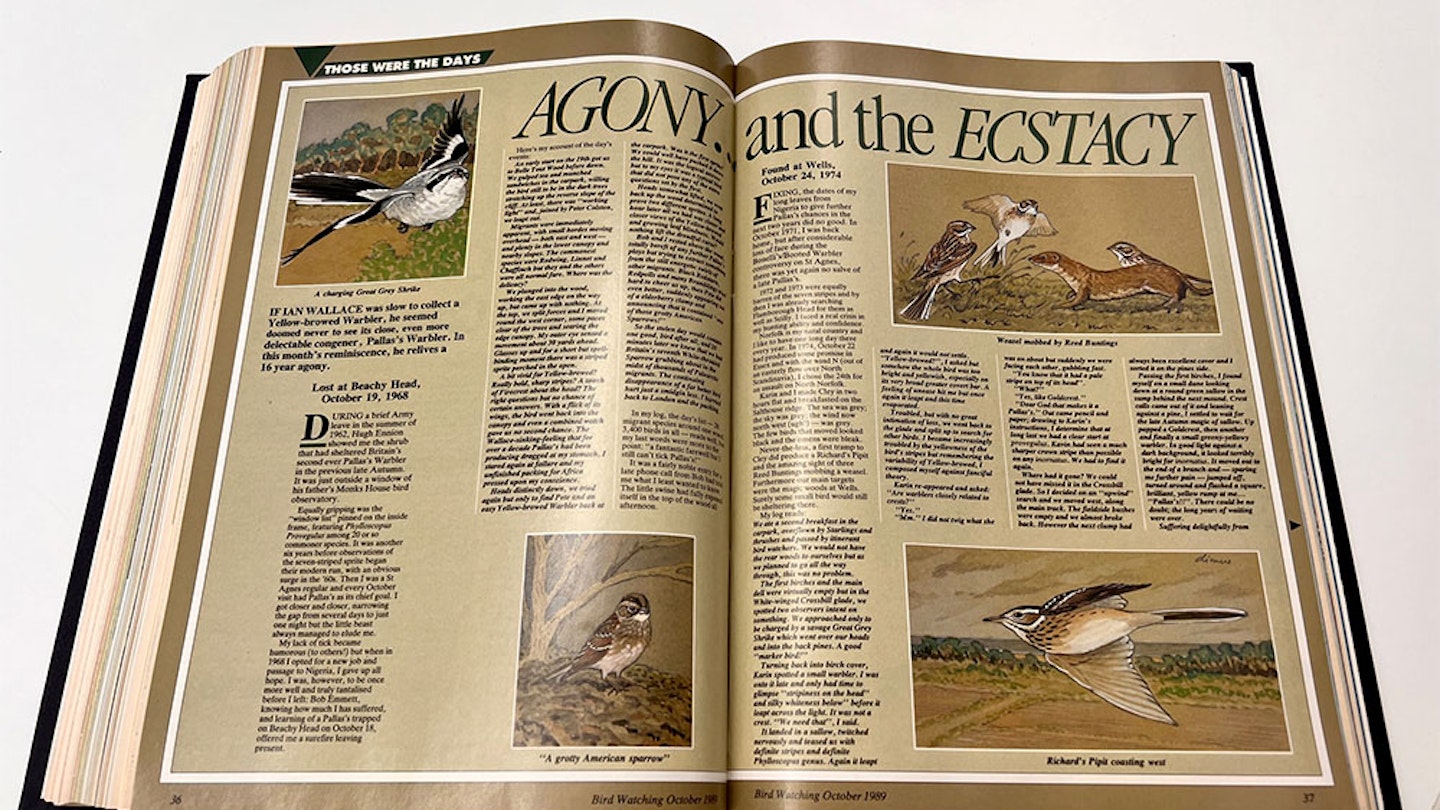

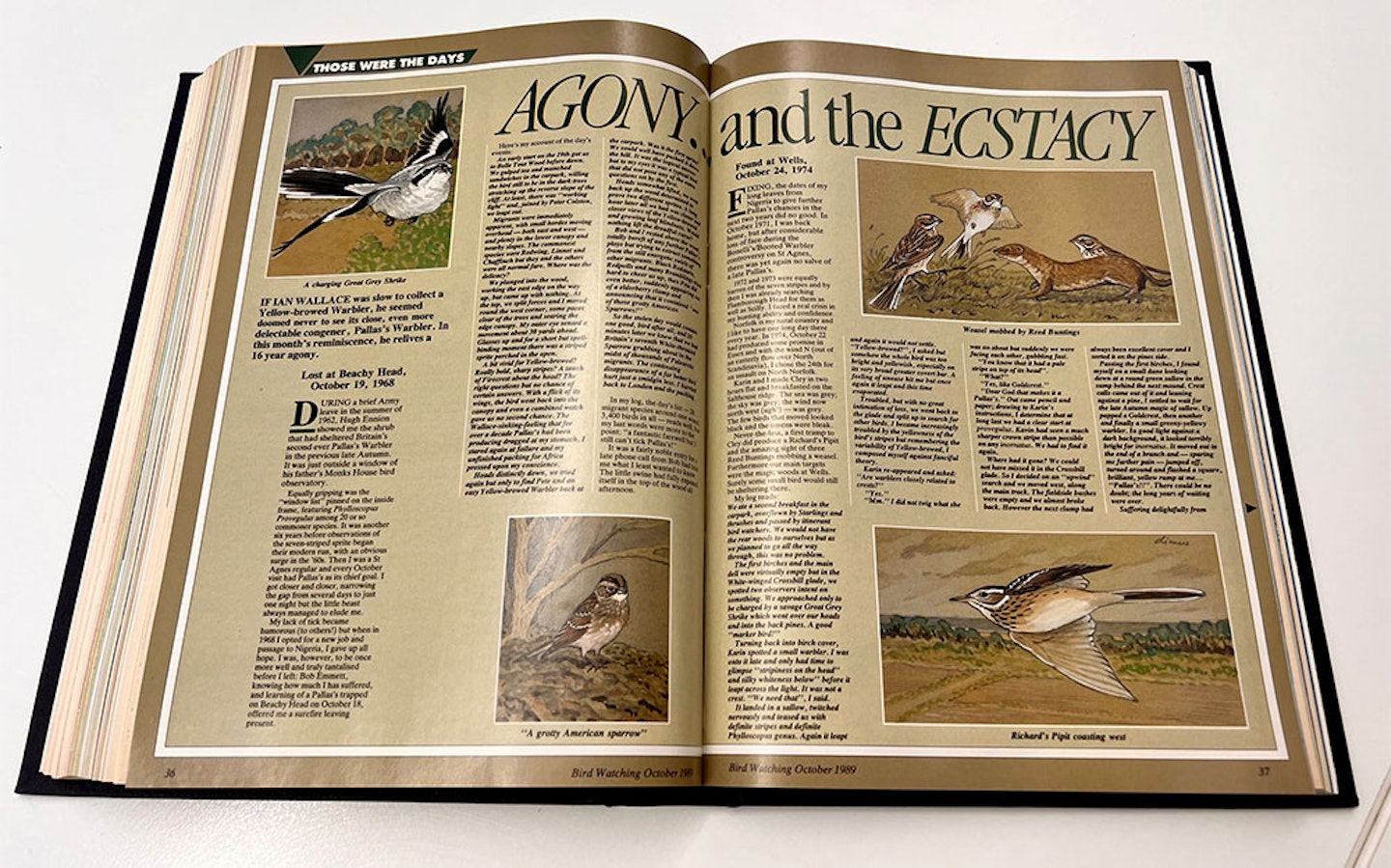

Agony… and the ecstacy

October 1989

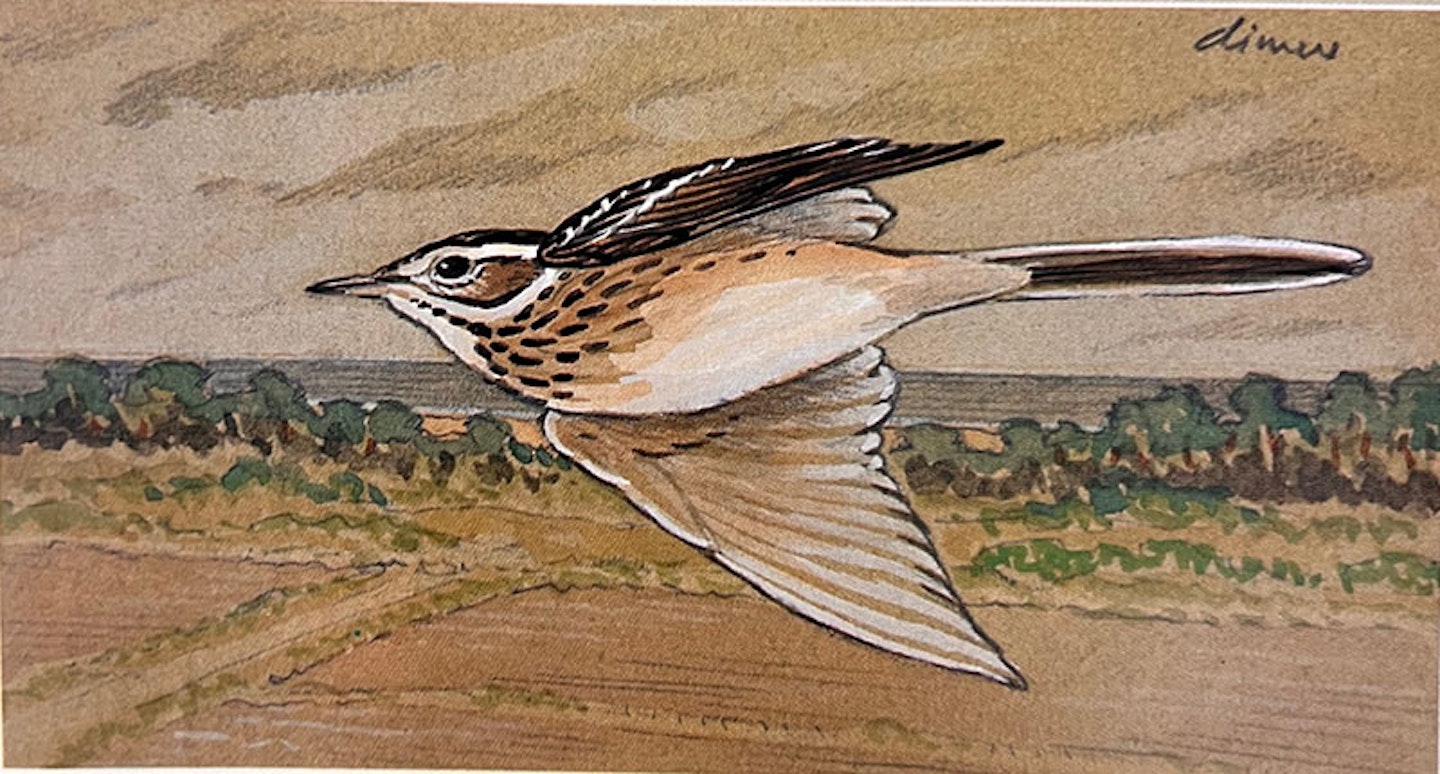

If Ian Wallace was slow to collect a Yellow-browed Warbler, he seemed doomed never to see its close, even more delectable congener, Pallas’ Warbler. In this month’s reminiscence, he relives a 16 year agony.

Lost at Beachy Head, 19 October 19 1968

During a brief Army leave in the summer of 1962, Hugh Ennion showed me the shrub that had sheltered Britain’s second ever Pallas’s Warbler in the previous late Autumn. It was just outside a window of his father’s Monks House bird observatory. Equally gripping was the “window list” pinned on the inside frame, featuring Phylloscopus proregulus [Pallas’s Warbler] among 20 or so commoner species.

It was another six years before observations of the seven-striped sprite began their modern run, with an obvious surge in the 1960s. Then, I was a St Agnes regular and every October visit had Pallas’s as its chief goal. I got closer and closer, narrowing the gap from several days to just one night, but the little beast always managed to elude me.

My lack of tick became humorous (to others!), but when in 1968, I opted for a new job and passage to Nigeria, I gave up all hope. I was, however, to be once more well and truly tantalised before I left: Bob Emmett, knowing how much I has suffered and learning of a Pallas’s trapped on Beachy Head on October 18, offered me a sure-fire leaving present.

Here’s my account of the day’s events:

An early start on the 19th got us to Belle Tout Wood before dawn. We gulped tea and munched sandwiches in the car park, willing the bird still to be in the dark trees stretching up the reverse slope of the cliff. At least, there was “working light” and, joined by Peter Colston, we leapt out.

Migrants were immediately apparent, with small hordes moving overhead – both east and west – and plenty in the lower canopy and nearby slopes. The commonest species were Redwing, Linnet and Chaffinch, but they and the others were all normal fare. Where was the delicacy?

We plunged into the wood, working the east edge on the way up, but came up with nothing. At the top, we split forces and I moved round the west corner, some paces clear of the trees and searing the edge canopy. My outer eye sensed a movement about 30 yards ahead. Glasses up and for a short but spell-binding moment there was a striped sprite perched in the open. A bit vivid for Yellow-browed? Really bold, sharp stripes? A touch of Firecrest about the head? The right questions, but no chance of certain answers.

With a flick of its wings, the bird went back into the canopy and even a combined watch gave us no second chance. The Wallace-sinking-feeling that for more than a decade Pallas’s had been producing, dragged at my stomach. I stared again at failure and my unfinished packing for Africa pressed upon my conscience.

Heads distinctly down, we tried again but only to find Pete and an easy Yellow-browed Warbler back at the car park. Was it the first sprite? We could well have pushed it down the hill. It was the logical answer, but to my eyes it was a typical bird that did not pose any of the extra questions set by the first. Heads somewhat lifted, we went back up the wood determined to prove two different sprites.

A long hour later, all we had was closer and closer views of the Yellow-browed and growing leaf blindness. Would nothing lift the dreadful curse? Bob and I rested above the wood, totally bereft of any further Pallas’s ploys but trying to extract something from the still energetic swirls of other migrants. Black Redstarts, Redpolls and many Bramblings tried hard to cheer us up, then Pete did even better, suddenly appearing out of a Elderberry clump and announcing that it contained “one of those grotty American Sparrows!”

So, the stolen day would contain one good bird after all, and 20 minutes later we knew that we had Britain’s seventh White-throated Sparrow grubbing about in the midst of thousands of Palearctic migrants. The continuing disappearance of a far better bird hurt just a smidgin less.

I hurried back to London and the packing. In my log, the day’s list – 28 migrant species around one wood; 3,400 birds in all – reads well, but my last words were more to the point: “‘a fantastic farewell, but I still can’t tick Pallas’s!” It was a fairly noble entry for a late phone call from Bob had told me what I least wanted to know. The little swine had fully exposed itself in the top of the wood all afternoon.

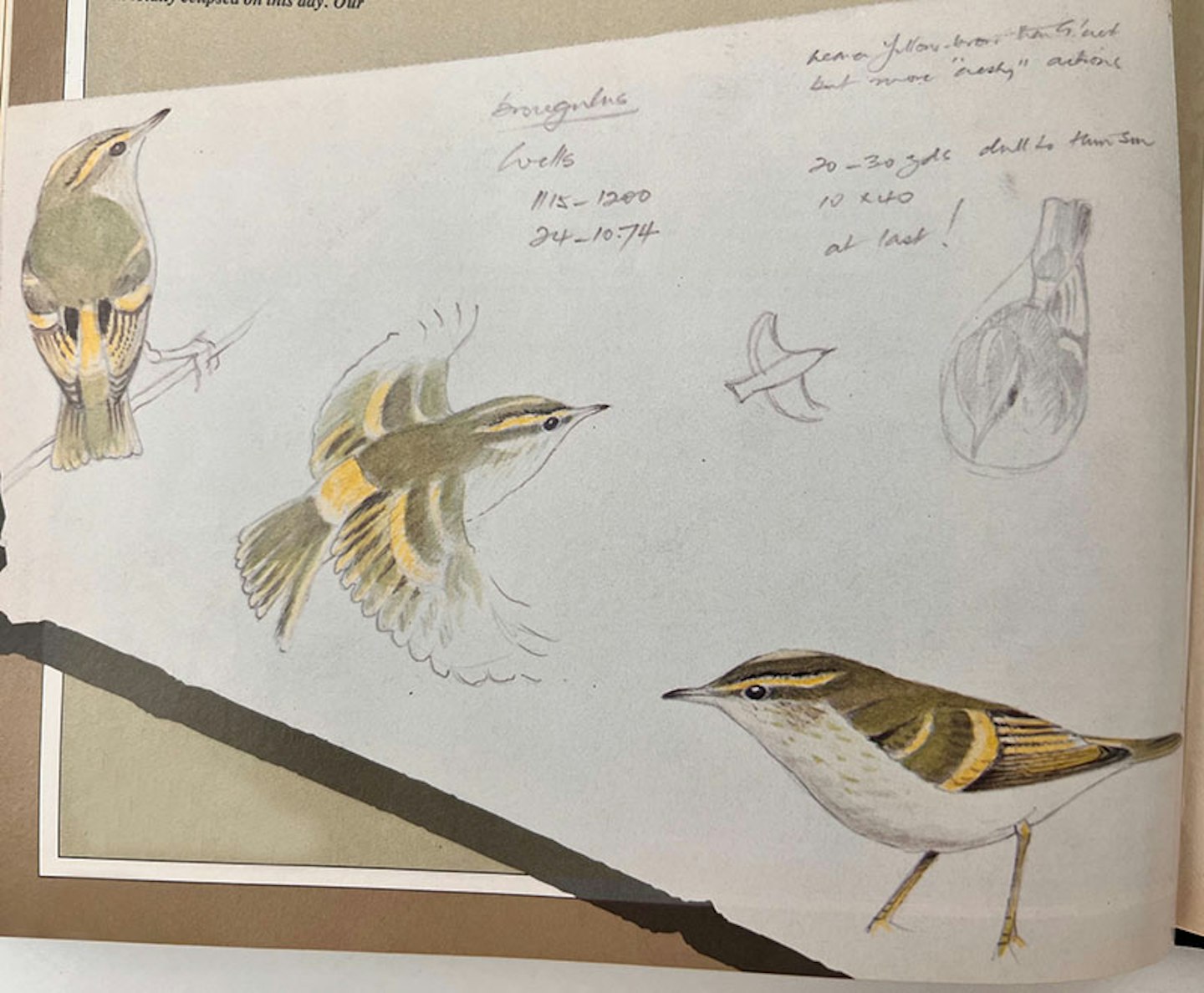

Found at Wells, 24 October 1974

Fixing the dates of my long leaves from the dates of my Nigeria to give further Pallas’s chances in the next two years did no good. In October 1971, I was back home, but after considerable loss of face during the Bonelli’s/Booted Warbler controversy on St Agnes, there was yet again no salve of a late Pallas’s. 1972 and 1973 were equally barren of the seven stripes and by then I was already searching Flamborough Head for them as well as Scilly.

I faced a real crisis in my hunting ability and confidence. Norfolk is my natal country and I like to have one long day there every year. In 1974, 22 October had produced some promise in Essex and with the wind N (out of an easterly flow over North Scandinavia), I chose the 24th for an assault on North Norfolk.

Karin and I made Cley in two hours flat and breakfasted on the Salthouse ridge. The sea was grey; the sky was grey; the wind now north-west (ugh!) was grey. The few birds that moved looked black and the omens were bleak. Never-the-less, a first tramp to Cley did produce a Richard’s Pipit and the amazing sight of three Reed Buntings mobbing a weasel.

Furthermore, our main targets were the magic woods at Wells. Surely, some small bird would still be sheltering there.

My log reads:

We ate a second breakfast in the car park, overflown by Starlings and thrushes and passed by itinerant birdwatchers. We would not have the rear woods to ourselves, but as we planned to go all the way through, this was no problem. The first Birches and the main dell were virtually empty but in the ‘White-winged Crossbill glade’, we spotted two observers intent on something.

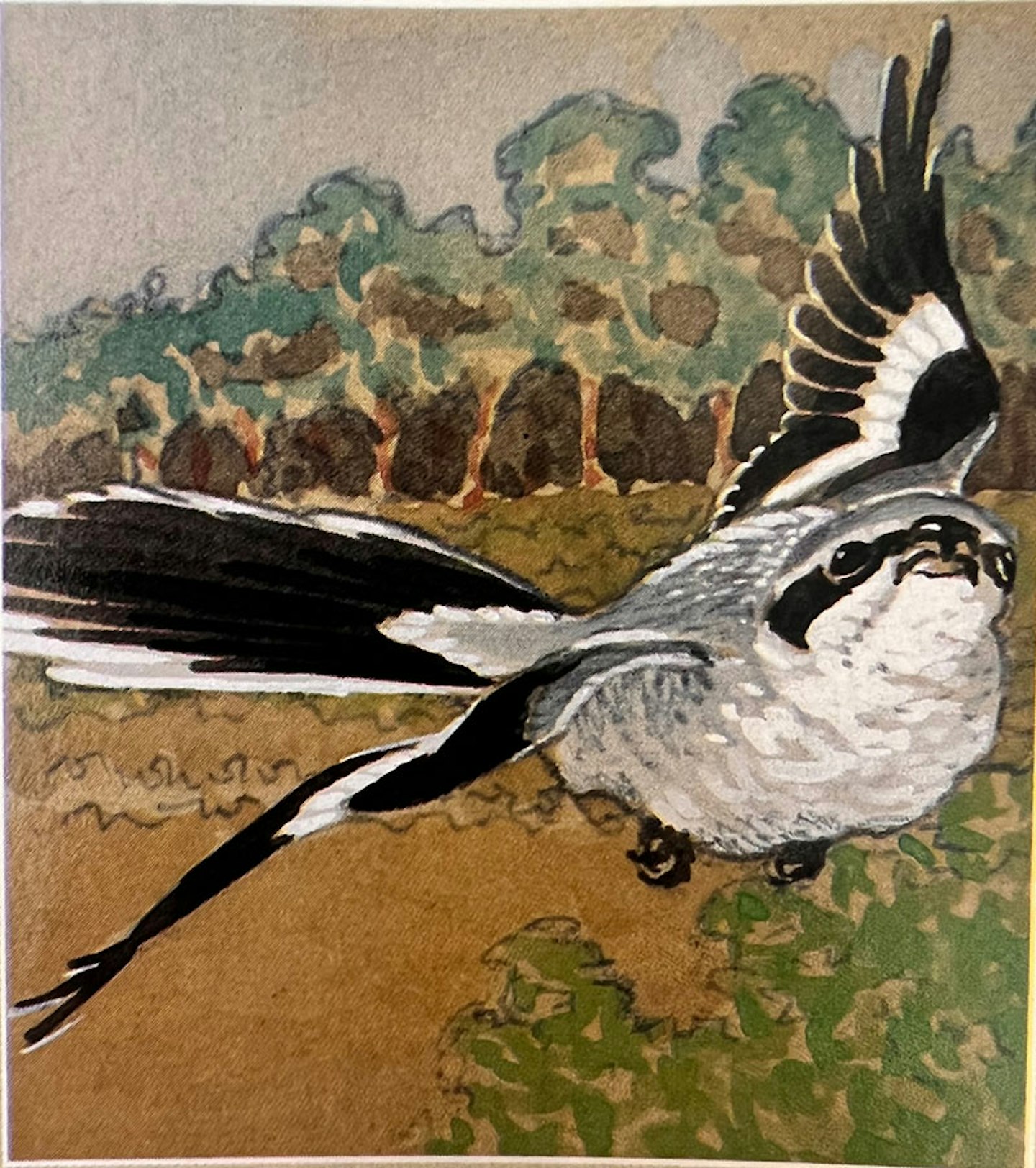

We approached only to be charged by a savage Great Grey Shrike, which went over our heads and into the back pines. A good “marker bird!?” Turning back into Birch cover, Karin spotted a small warbler. I was onto it late and only had time to glimpse “‘stripiness on the head”‘ and silky whiteness below” before it leapt across the light. It was not a crest. “We need that”, I said. It landed in a sallow, twitched nervously and teased us with definite stripes and definite Phylloscopus genus.

Again it leapt and again it would not settle. “Yellow-browed?”, I asked but somehow the whole bird was too bright and yellowish, especially on its very broad greater covert bar. A feeling of unease hit me, but once again it leapt and this time evaporated.

Troubled, but with no great intimation of loss, we went back to the glade and split up to search for other birds. I became increasingly troubled by the yellowness of the bird’s stripes but remembering the variability of Yellow-browed, I composed myself against fanciful theory. Karin re-appeared and asked:

“Are warblers closely related to crests?”

“Yes”.

“Mm.”

I did not twig what she was on about but suddenly we were facing each other, gabbling fast. “You know that it had a pale stripe on top of its head”

“What?”

“Yes, like Golderest.”

“Dear God that makes it a Pallas’s.”

Out came pencil and paper; drawing to Karin’s instructions, I determine that at long last we had a clear start at proregulus. Karin had seen a much sharper crown stripe than possible on any inornatus [Yellow-browed]. We had to find it again. Where had it gone?

We could not have missed it in the ‘Crossbill glade’. So I decided on an “upwind’ search and we moved west, along the main track. The fieldside bushes were empty and we almost broke back. However, the next clump had always been excellent cover and I sorted it on the pines side. Passing the first Birches, I found myself on a small dune looking down at a round green sallow in the sump behind the next mound.

Crest calls came out of it and leaning against a pine, I settled to wait for the late autumn magic of sallow. Up popped a Goldcrest, then another, and finally a small greeny-yellowy warbler. In good light against a dark background, it looked terribly bright for inornatus. It moved out to the end of a branch and – sparing me further pain – jumped off, turned around and flashed a square, brilliant, yellow rump at me. “Pallas’s!!”.

There could be no doubt; the long years of waiting were over. Suffering delightfully from adrenalin surge and total joy, I ran for Karin, extracted her from a birch clump and told her that we had indeed found our very own proregulus. Back at the sallow, the sprite behaved splendidly and showed its true colours well. As Bob had noted with another earlier in the week, the rump winked with each wing flick but it struck me as surprisingly large and lacking in the black marks so obvious in skins. (In fact the bird is as variable as inornatus).

From behind, we became surrounded by a group of West Midland Bird Club members and we were able to give them a happy hour, with 20 Pallas’s ticks accomplished for assorted ladies and gents. “We have an expert from the Rare Birds Committee in our party; just wait till we tell him,” was a gem comment from one, she and her companions unaware that the committee’s then Chairman had been their guide to a shared fortune.

Left alone, we decided to compare our best ever warbler with a Yellow-browed which some of the group had seen in the dell. So back we went and eventually some loud calls put us on to it, a grey humei type bird (from SW Asia) as nice as ever, but totally eclipsed on this day.

Our study of it cost us Waxwing and Lesser Spotted Woodpecker which pitched in by the Pallas’s, but we fixed the differences between the two species once and for all. I became even happier when I realised that at last I had the then full set of British Phylloscopi, all but one self-found.

We celebrated with more food and a change of scene. Holkham Gap produced another crunching Great Grey Shrike and another of the earlier Richard’s Pipit, coasting west. Away from the trees, there was too much wind to work any more small birds, but suddenly the sun broke through to gild an already hallowed day.

We drove back to Cley to pass on the good news, but amazingly, there was not a birdwatcher in sight. A pale, at least Scandinavian, Chiffchaff at Walsey Hills pool was our very last bird. At night the Royal Festival Hall and the Schumann A minor combined to allow further celebration of a most beautiful and brave little bird and its ending of a 16 year old agony?

Statistically I should have gone many more years before my second (or third?!) Pallas’s, but in 1975 three more came my way in that year’s amazing flood of Siberian birds. In the next decade, my increasing concentration on Flamborough Head produced almost annual meetings with the seven-striped sprite. Just one wish about it remains to be fulfilled and that is to see a Pallas’s, a Yellow-browed and a Firecrest in the same field of view, as Brian Milne once did in the St Agnes orchard. That’s what I call a grip!