August 1989

Poles apart

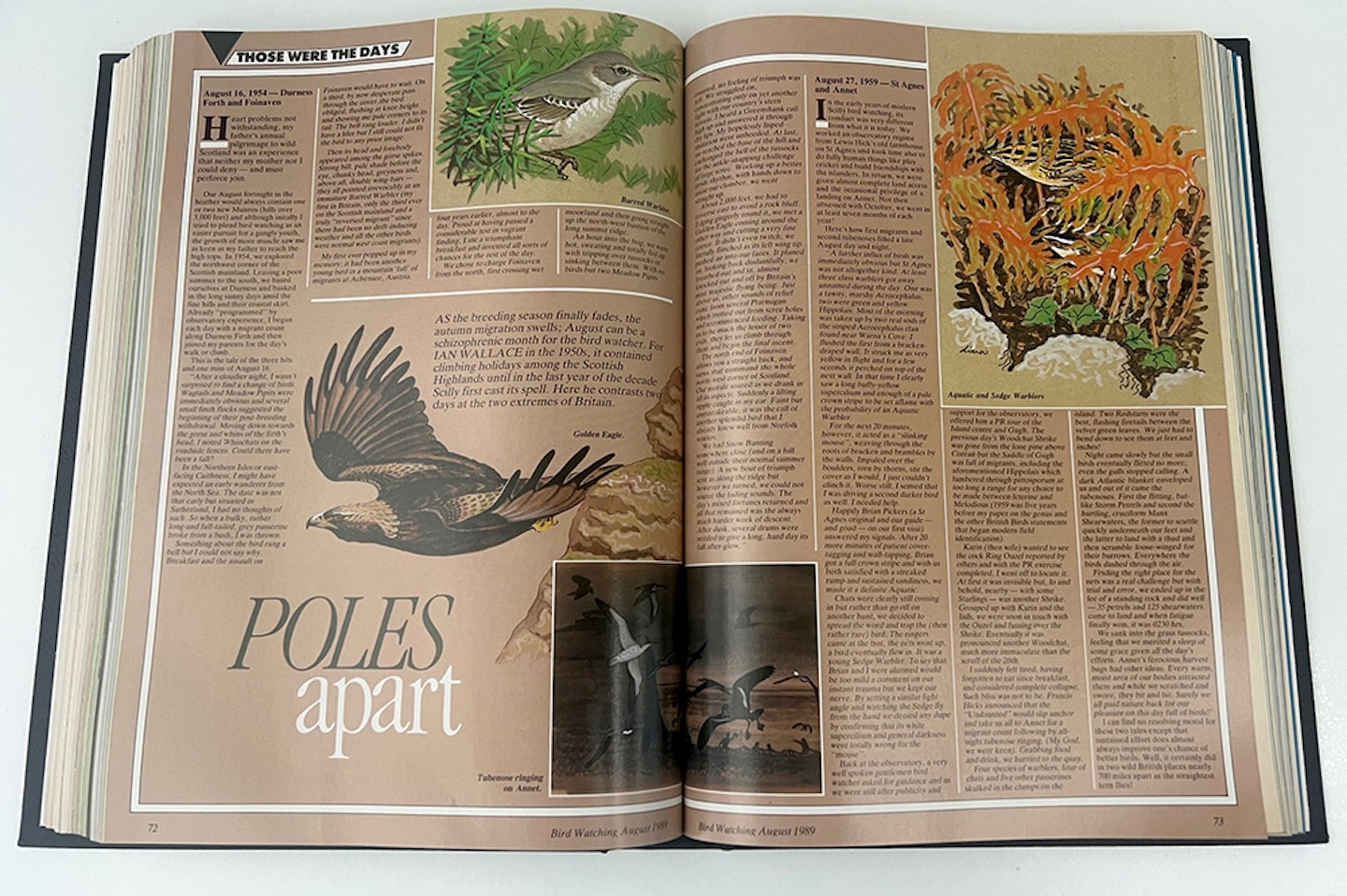

As the breeding season finally fades, the autumn migration swells; August can be a schizophrenic month for the bird watcher. For Ian Wallace in the 1950s, it contained climbing holidays among the Scottish Highlands until in the last year of the decade Scilly first cast its spell. Here he contrasts twa days at the two extremes of Britain.

16 August 1954 – Durness Forth and Foinaven

Heart problems not withstanding, my father’s annual pilgrimage to wild Scotland was an experience that neither my mother nor I could deny – and must perforce join.

Our August fortnight in the heather would always contain one or two new Munros (hills over 3,000 feet) and although initially I tried to plead birdwatching as an easier pursuit for a gangly youth, the growth of more muscle saw me as keen as my father to reach the high tops. In 1954, we explored the north-west corner of the Scottish mainland. Leaving a poor summer to the south, we based ourselves at Durness and basked in the long sunny days amid the fine hills and their coastal skirt. Already “programmed” by observatory experience, I began each day with a migrant count along Durness Firth and then joined my parents for the day’s walk or climb.

This is the tale of the three hits and one miss of August 16.

After a cloudier night, I wasn’t surprised to find a change of birds. Wagtails and Meadow Pipits were immediately obvious and several small finch flocks suggested the beginning of their post-breeding withdrawal. Moving down towards the gorse and whins of the firth’s head. I noted Whinchats on the roadside fences. Could there have been a fall?

In the Northern Isles or east-facing Caithness, I might have expected an early wanderer from the North Sea. The date was not that early, but situated in Sutherland, I had no thoughts of such. So, when a bulky, rather long-and full-tailed, grey passerine broke from a bush, I was thrown.

Something about the bird rang a bell but I could not say why. Breakfast and the assault on Foinaven would have to wait. On a third, by now desperate, pass through the cover, the bird obliged, flushing at knee height and showing me pale corners to its tail. The bell rang louder. I didn’t have a lifer, but I still could not fit the bird to any prior image.

Then its head and forebody appeared among the gorse spikes. Strong bill, pale shade before the eye, chunky head, greyness and, above all, double wing-bars they all pointed irrevocably at an immature Barred Warbler (my first in Britain, only the third ever on the Scottish mainland and a truly “reversed migrant”, since there had been no drift-inducing weather and all the other birds were normal west coast migrants).

My first ever popped up in my memory; it had been another young bird in a mountain ‘fall’ of migrants at Achensee, Austria, four years earlier, almost to the day. Proud at having passed a considerable test in vagrant finding, I ate a triumphant breakfast and invented all sorts of chances for the rest of the day.

We chose to charge Foinaven from the north, first crossing wet moorland and then going straight up the north-west bastion of the long summit ridge.

An hour into the bog, we were hot, sweating and totally fed up with tripping over tussocks or sinking between them. With no birds but two Meadow Pipits counted, no feeling of triumph was left. We struggled on, concentrating only on yet another fight with our country’s stern terrain. I heard a Greenshank call high up and answered it through dry lips. My hopelessly lisped imitation went unheeded. At last, we reached the base of the hill and exchanged the hell of the tussocks for the ankle-snapping challenge of large scree. Working up a better stride rhythm, with hands down to assist our clamber, we went straight up.

About 2,000 feet, we had to traverse east to avoid a rock bluff. Edging gingerly round it, we met a Golden Eagle coming around the other way and cutting a very fine corner. It didn’t even twitch; we literally flinched as its left wing tip pushed air into our faces. It planed on, looking back disdainfully; we breathed out and in, almost knocked out and off by Britain’s most majestic flying being.

Just above us, other sounds of relief came from several Ptarmigan which trotted out from scree holes and recommenced feeding. Taking us to be much the lesser of two evils, they let us climb through them and begin the final ascent.

The north end of Foinaven allows you a straight back, and views that command the whole north-west corner of Scotland. Our morale soared as we drank in all its aspects. Suddenly a lilting ripple caught in my ear. Faint but unmistakeable, it was the call of another splendid bird that I already knew well from Norfolk winters.

We had Snow Bunting somewhere close (and on a hill well outside their normal summer range). A new bout of triumph sent us along the ridge, but however we turned, we could not source the fading sounds. The day’s mixed fortunes returned and all that remained was the always much harder work of descent. After dusk, several drams were needed to give a long, hard day its full after-glow.

27 August 1959 – St Agnes and Annet

In the early years of modern Scilly birdwatching, its conduct was very different from what it is today. We worked an observatory regime from Lewis Hick’s old farmhouse on St Agnes and took time also to do fully human things like play cricket and build friendships with the islanders. In return, we were given almost complete land access and the occasional privilege of a landing on Annet. Not then obsessed with October, we went in at least seven months of each year!

Here’s how first migrants and second tubenoses filled a late August day and night.

A further influx of birds was immediately obvious, but St Agnes was not altogether kind. At least three class warblers got away unnamed during the day. One was a tawny, ‘Marshy’ Acrocephalus; two were green and yellow Hippolais. Most of the morning was taken up by two real sods of the striped Acrocephalus clan found near Warna’s Cove. I flushed the first from a bracken-draped wall. It struck me as very yellow in flight and for a few seconds, it perched on top of the next wall. In that time I clearly saw a long buffy-yellow supercilium and enough of a pale crown stripe to be set aflame with the probability of an Aquatic Warbler.

For the next 20 minutes, however, it acted as a “slinking mouse” weaving through the roots of bracken and brambles by the walls. Impaled over the boulders, torn by thorns, stir the cover as I would, I just couldn’t clinch it. Worse still, I sensed that I was driving a second darker bird as well. I needed help.

Happily, Brian Pickers (a St Agnes original and our guide and goad – on our first visit) answered my signals. After 20 more minutes of patient cover-tugging and wall-tapping, Brian got a full crown stripe and with us both satisfied with a streaked rump and sustained sandiness, we made it a definite Aquatic.

Chats were clearly still coming in, but rather than go off on another hunt, we decided to spread the word and trap the (then rather rare) bird. The ringers came at the trot, the nets went up, a bird eventually flew in. It was a young Sedge Warbler. To say that Brian and I were alarmed would be too mild a comment on our instant trauma, but we kept our nerve. By setting a similar light angle and watching the Sedge fly from the hand we denied any dupe by confirming that its white supercilium and general darkness were totally wrong for the “mouse”.

Back at the observatory, a very well spoken gentlemen birdwatcher asked for guidance and as we were still after publicity and support for the observatory, we offered him a PR tour of the Island centre and Gugh. The previous day’s Woodchat Shrike was gone from the lone pine above Corean but the Saddle of Gugh was full of migrants, including the aforementioned Hippolais which lumbered through pittosporum at too long a range for any choice to be made between Icterine and Melodious (1959 was five years before my paper on the genus and the other British Birds statements that began modern field identification).

Karin (then wife) wanted to see the cock Ring Ouzel reported by others and with the PR exercise completed, I went off to locate it. At first it was invisible but, lo and behold, nearby – with some Starlings – was another shrike. Grouped up with Karin and the lads, we were soon in touch with the ouzel and fussing over the shrike. Eventually, it was pronounced another Woodchat, much more immaculate than the scruff of the 26th.

I suddenly felt tired, having forgotten to eat since breakfast, and considered complete collapse. Such bliss was not to be. Francis Hicks announced that the Undaunted would slip anchor and take us all to Annet for a migrant count following by all-night tubenose ringing. (My God, we were keen). Grabbing food and drink, we hurried to the quay.

Four species of of warblers, for of chats and five other passerines skulked in the clumps on the island. Two Redstarts were the best, flashing firetails between the velvet green leaves. We just had to bend down to see them at feet and inches!

Night came slowly but the small birds eventually flitted no more; even the gulls stopped calling. A dark Atlantic blanket enveloped us and out of it came the tubenoses. First the flitting, bat-like Storm Petrels and second the hurtling, cruciform Manx Shearwaters, the former to scuttle quickly underneath our feet and the latter to land with a thud and then scramble loose-winged for their burrows. Everywhere the birds dashed through the air.

Finding the right place for the nets was a real challenge but with trial and error, we ended up in the lee of a standing rock and did well: 35 petrels and 125 shearwaters came to land, and when fatigue finally won, it was 0230 hrs.

We sank into the grass tussocks, feeling that we merited a sleep of some grace given all the day’s efforts. Annet’s ferocious harvest bugs had other ideas. Every warm, moist area of our bodies attracted them and while we scratched and swore, they bit and bit. Surely, we all paid nature back for our pleasure on this day full of birds!

I can find no resolving moral for these two tales except that sustained effort does almost always improve one’s chance of better birds. Well, it certainly did in two wild British places nearly 700 miles apart as the straightest tern flies!