Five spring teasers

Spring has become our year's most fitful season but even after 45 differing years in the field, Ian Wallace still finds March full of incoming birds. Here he looks at five passerines that move north quickly.

Since the mid-1970s, the study of broad front migration has lost its broad brush. Apart from Bird Watching's own remarkable county-by-county, month-by-month reports, no national journal nor annual report is publishing more than terse summaries, cameos of unusual specific migrations and rarity lists.

We are losing the perspectives of normal movements. What a shame that the BTO's Bird Migration was so shortlived and that its occasional modern replacements get so little attention.

In the brief 1960s’ life of Bird Migration, the editors, Ken Williamson and Peter Davis harvested much more than rarities and gave even single observers working only local patches chances to contribute to the national picture of each passage season. One scheme co-ordinated inland observation points with coastal observatories.

Very few results were analysed but I have never forgotten that one was the display of widely shifting Goldcrests in February, when most of us would have assumed these tiny mites still to be locked up in the warmest conifer canopy available. It was a classic example of how fascinating common migrants can be.

How can you share in such phenomena? One way is to start your own regular counts of a mixed set of habitats this spring. In this article, I introduce you to five target species which sound simple but, as you will see, are actually far from that.

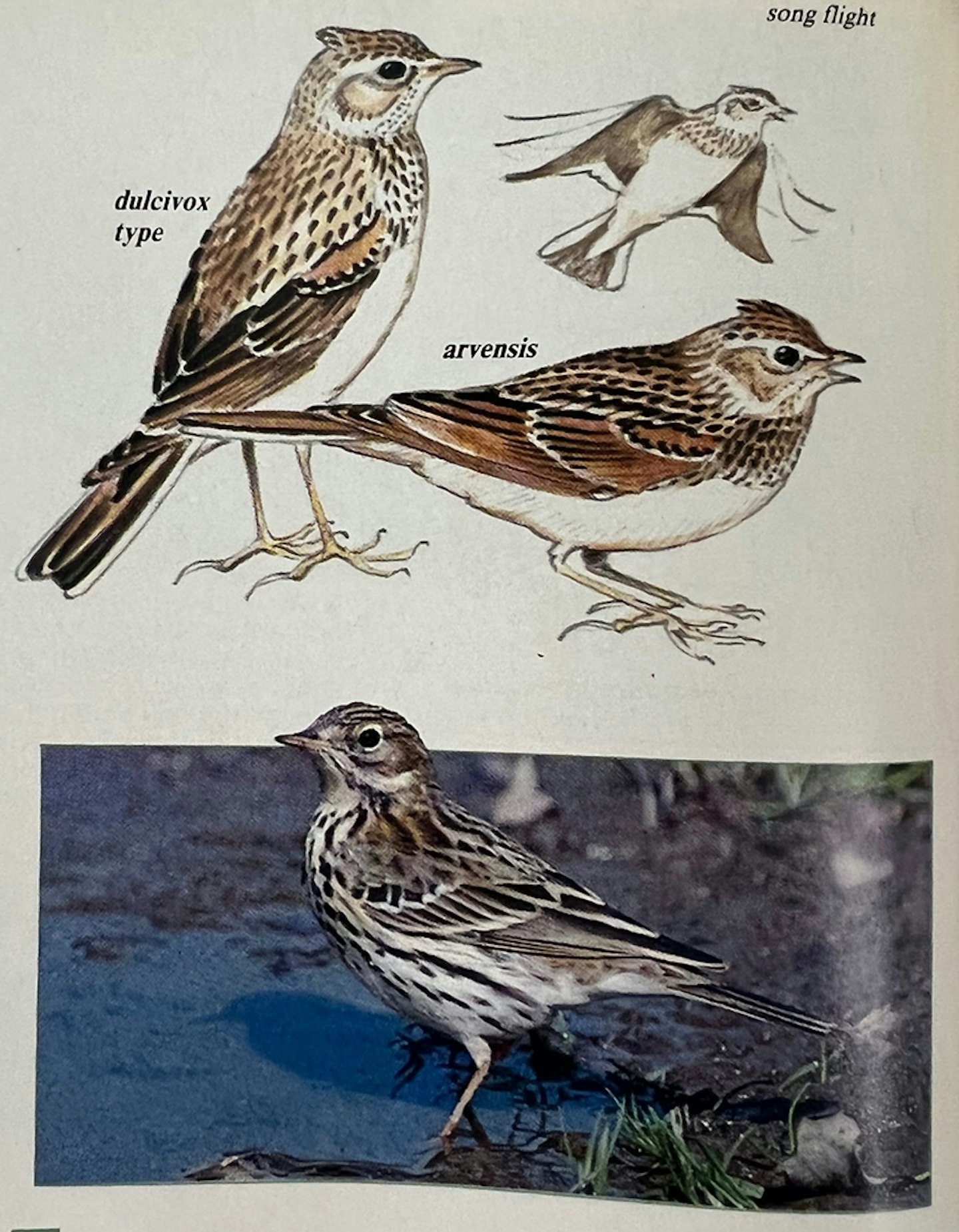

Sky Lark

British and lrish birds are now divided into two races scotia in Scotland. Ireland and north-west England and typical arvensis in Wales and the rest of England. The Handbook also accepted – under the name intermedia – birds of an eastern race but sadly in 1971, the BOU sent them into limbo. This is rather a shame as large, pale Sky Larks resembling dulcivox from as close as eastern Russia still appear among classic European migrants.

Our birds are mainly sedentary, judging by most ringing recoveries, but their upland contingents and the others in time of full snow cover do move. Thus the commonest lark makes a fascinating target for the migration student. Its Spring return and passage can be seen from mid February to mid-May.

The BOU concedes that the movements include birds from central and northern Europe but there is no scientific reason why a few birds from near Asia should not to be intermingled with both migrations.

Since individual Sky Larks do vary considerably, the separation of races is no easy task but in general, Scotia is darker. more rufous above, with wider beak streaks, and warmer, more rufous than buff on its chest than arvensis, while dulcivox is bulkier, distinctively pink-buff to grey above with sharper streaks, and little more than cream on its chest.

Even to suspect the presence of a vagrant race, you must get to know your own birds very well. So the trick is to sit among some local breeders and spot the odd ones as they pass through them.

I have done this (at least to my own satisfaction) in my last two study areas in North Humberside and East Staffordshire. Even if you are not intrigued by such attempts at field taxonomy, there are always the added specific benefits of that amazing, hovering song-flight and that indomitable song!

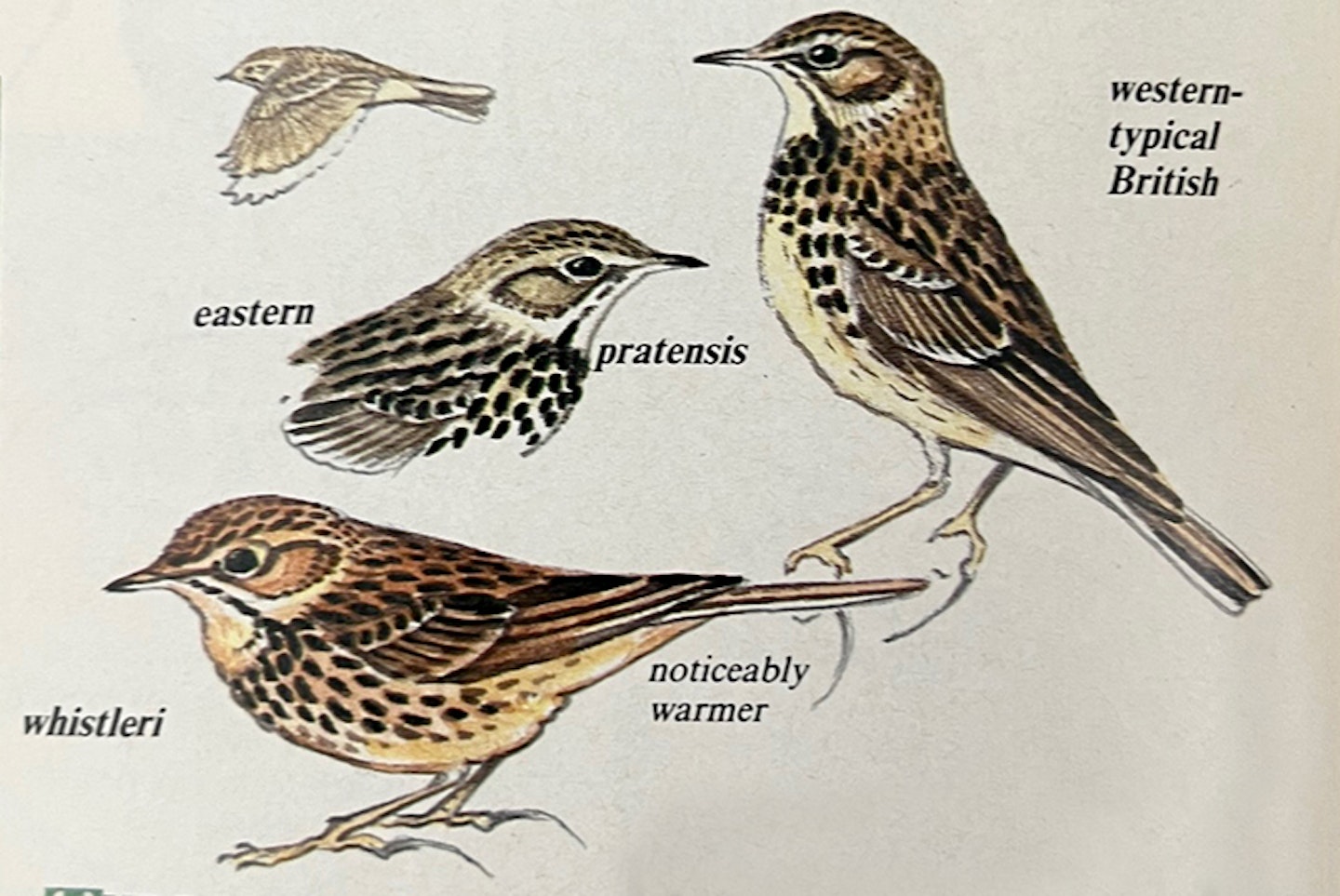

Meadow Pipit

THE British and Irish birds come in two races whistleri in Ireland and western Scotland and typical pratensis elsewhere in Britain and across the range of the species to western Siberia. Like the Sky Lark, our commonest pipit comes in various shades above and below but a full "north- westerner" is markedly redder- brown, less olive on its upperparts and warmer and more fully buff on its underparts. In years of heavy falls from accidental intermingled passage, such birds appear well away from their western haunts, standing out like sore thumbs if they rub shoulders with the paler Scandinavian and Russian birds. Unlike Sky Larks, our Meadow Pipits move freely, deserting all uplands and exposed countryside in winter, and their spring return and passage from early March to mid-May can be as visible as those of later coming hirundines. All day movements occur once l followed birds all the way from Dungeness to London and large localised falls may drown almost any area, as the birds are brought down by rain or simply stop to rest and feed. With its jerky, sometimes hesitant flight, the Meadow Pipit looks fragile in the sky but as an early mass migrant, it has few equals in proclaiming spring. So why not give it close attention in 1989?

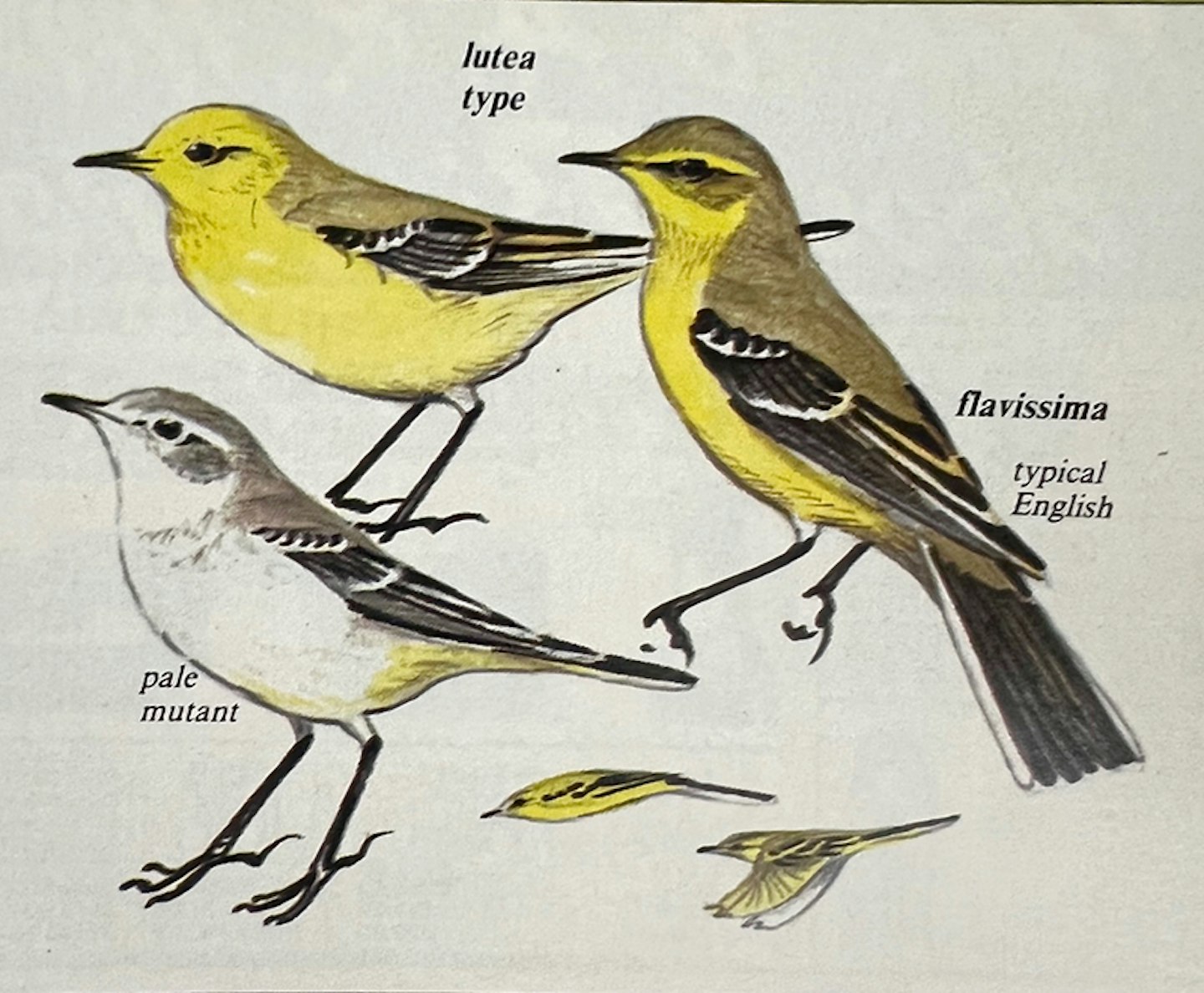

Yellow Wagtail

British and Europe's north-west coast birds are racially separated as flavissima. This Latin adjective means ‘most yellow’ but the description is not strictly accurate for that title really belongs to the fully yellow-headed lutea from south Russia which some, probably old British cocks resemble dangerously.

The Yellow Wagtail is another classically early spring migrant but unlike the lark and pipit, it comes all the way from tropical West Africa. A trickle begins in mid- March but the main arrival is usually in the first warm spell of April. Always the males precede the females by several days, as bright and as sure as a sign of spring as the daffodil.

Centuries of field drainage has not helped this delightful bird but it has held most of its ground. Look for it in the wetter parts of your patch or around the first put out herds of cattle which the wagtails like because they disturb insects.

The Yellow Wagtail and its other eastern races are plagued by loose genes and any close study of migrants or a breeding colony could find you pale mutants, true vagrants of the Blue-headed race flava and confusing but very intriguing hybrids. No population that I have studied has failed to present some truly pretty puzzles.

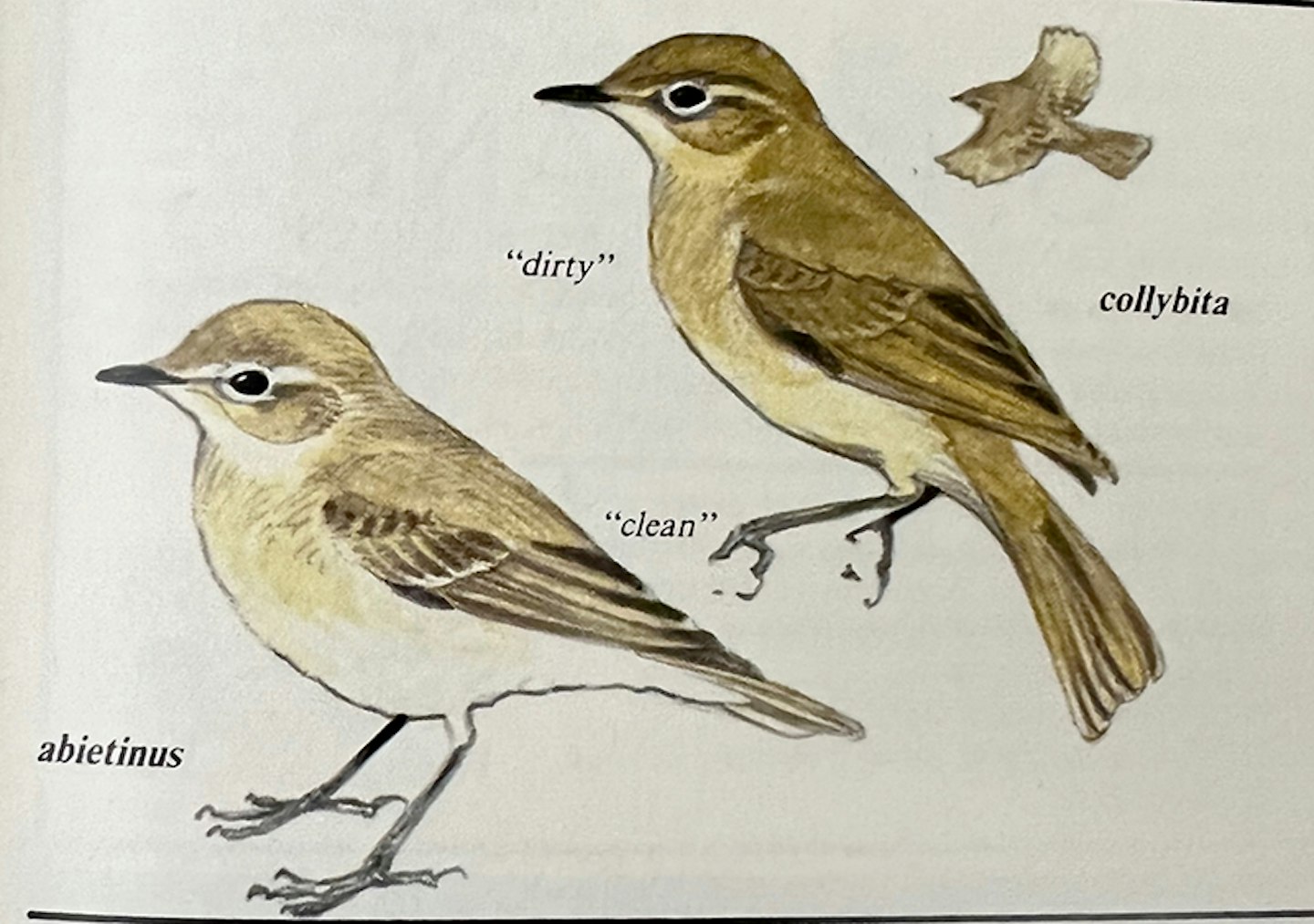

Chiffchaff

The English, Welsh and Irish and the increasing Scottish contingent are officially listed as typical collybita but like the Yellow Wagtail, this small warbler has rather unstable genes, often presenting within the usual rather swarthy birds, paler birds resembling the Scandinavian and Russian race abietinus and even approaching the west Siberain race fulvesceus.

Both dark and pale Chiffchaffs now winter widely in our lands, south of a Shannon/Anglesey/Humberside axis, and thus the sport of finding a first to match the cock Wheatear is less sure than it was in my youth.

Even so, there is still a marked influx of singing birds in late March and early April and the odds are that they are long distance migrants. The time-ticking song is so diagnostic that you can pass swiftly on to musing about their plumage variations. I had always assumed that abietinus was an East Coast migrant but blow me if my first Staffordshire bird in 1988 was not a morph too pale for any of my few local collybita!

Wheatear

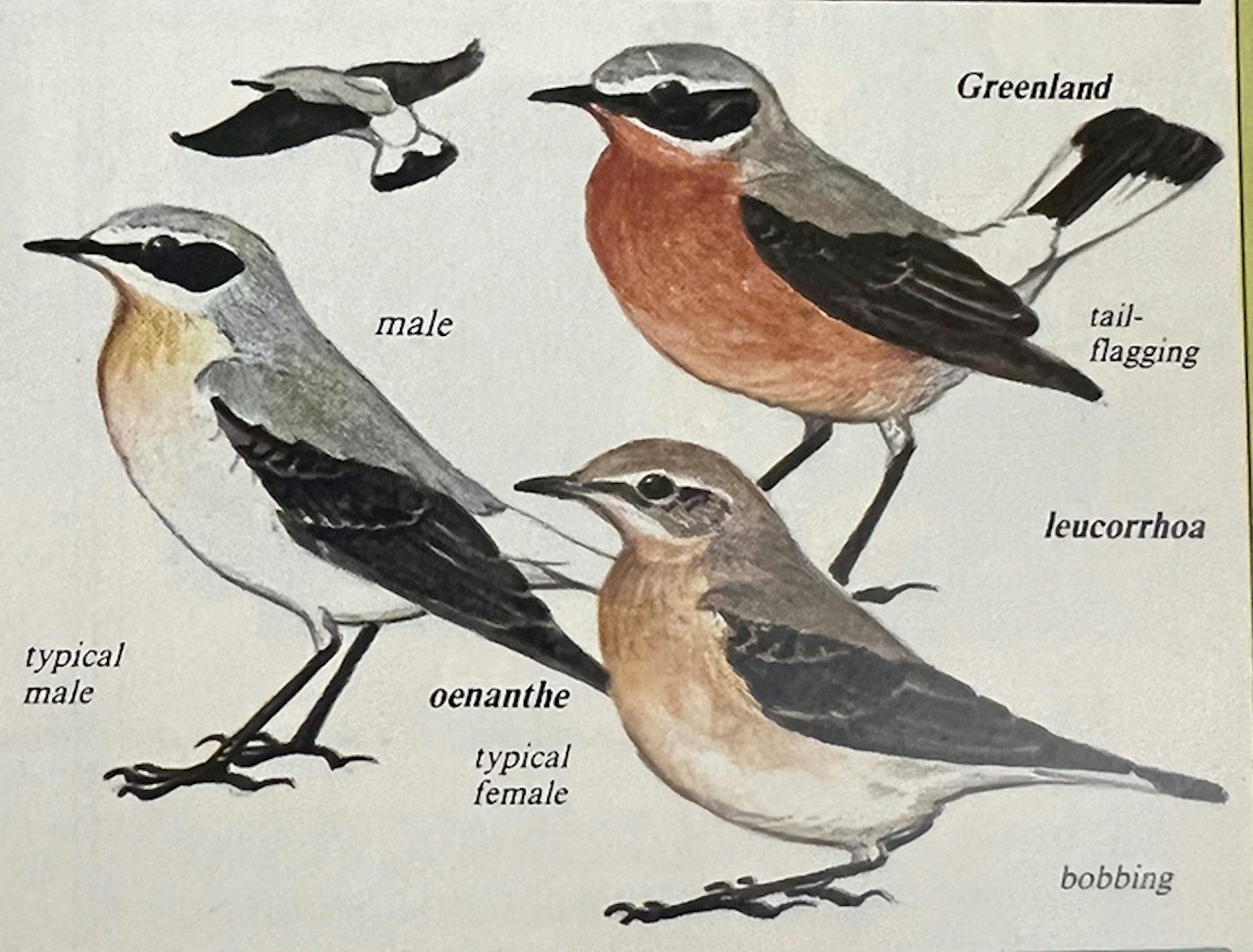

The British and Irish breeding birds are nominate oenanthe of fairly constant appearance, though a few show the overall pale look of the south Eurasian race libanotica. Though these pass the larger, bolder, darker Greenland and Iceland birds, called leucorrhoa, they are very unlikely to appear before the third week of April, whereas our birds regularly appear in early March and even occasionally in late February.

Indeed, in most years, a cock Wheatear should be the first summer visitor that you spot. In inland areas, I used to find them regularly in March on ‘brown land’ (late winter plough), but the increase in autumn cereal sowing has spoilt this ploy. These days, close grass sward or stony areas may make more sense.

Certainly, there is no more alert signal of an upland spring than a cock Wheatear – superbly dressed, eager, bobbing on rock or post. Like the Yellow Wagtails, the females are tardy, often two weeks so.

Don't forget the Greenlanders, for they make up one of the few, relatively easy to identify subspecies in our passerines. So, watch through your spring for a chance at one – up to 20% bigger than typical birds, it is in a class of its own and flies the North Atlantic too!

Populations and conclusion

None of our five spring targets is rare-their breeding populations are estimated at:

Sky Lark: two-four million pairs;

Meadow Pipit: at least three million pairs;

Yellow Wagtail: 25,000 pairs;

Wheatear: 80,000 pairs ;and

Chiffchaff: 300,000 pairs.

But as you will have understood, none of them are simple birds. All pose problems that can tease for a lifetime in the field. They are also at some risk due to habitat change and loss. So it makes sense not only to enjoy their puzzles but also to try to register their fortunes in your area, sending your findings to your county recorder.

In the last three springs and summers, I have discovered that my 10Km square has nowhere near the supposed national/average loading of Sky Larks; lost its breeding Meadow Pipits in 1987; sustains Yellow Wagtails only through the artificial juxtaposition of disused airport runways with manure stacks; attracts some but does not hold any Wheatears and is re-gaining only Chiffchaffs.

One right does not cancel four wrongs and we should do more to monitor our local bird fortunes. It is great fun to spot a grey, eastern Sky Lark but the more important question is what would spring be like without the chorus of the resident brown jobs?

So, please place any venture into racial identification of the five teasers in the broad practice of a migration and population study. You have my word that you will not be bored. ever.

P.S. "If you're thinking "What is he going on about with Latin names and races?," let me answer: well, I agree that they're not for every birdwatcher but if you want to see evolution at work. then the study of races (alias subspecies) really is a window on a miracle. The process of natural selection, even in our relatively small lands, has produced recognisable forms in less than 10,000 years or, related to all the known epochs of pre-history, in the blink of an eye. You don't have to go the Galápagos to be aware of evolution. Its happening right outside your door!