Big birds, great music

January 1989

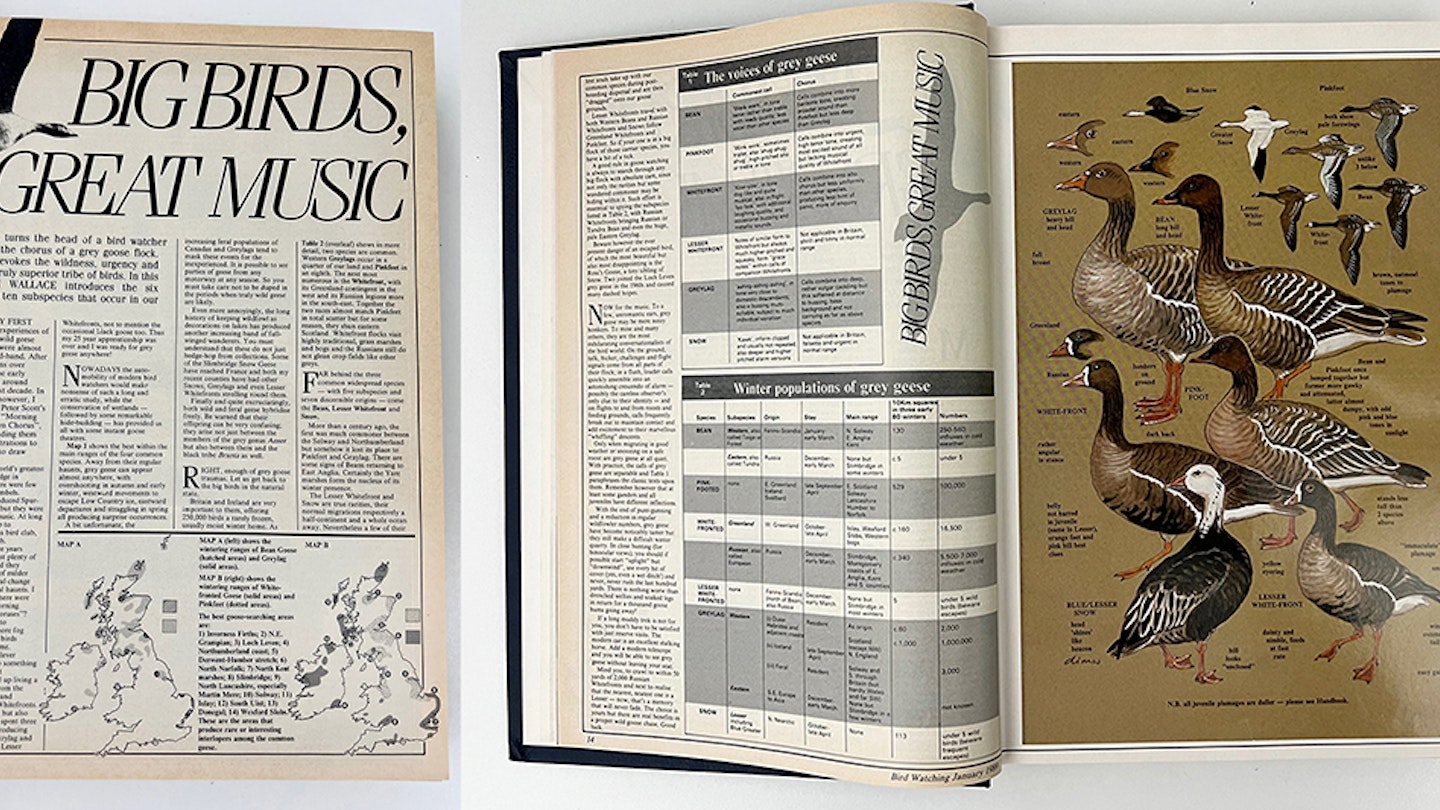

No sound turns the head of a birdwatcher faster than the chorus of a grey goose flock. Instantly it evokes the wildness, urgency and power of a truly superior tribe of birds. In this article, IAN WALLACE introduces the six species and 10 subspecies that occur in our lands.

MY FIRST experiences of wild geese were almost completely second-hand. After a few distant skeins over Lothian hills in the early 1940s, I saw none around London in the next decade. In the same period, however, I became a slave to Peter Scott’s marvellous books “Morning Flight” and “Dawn Chorus”, reading and re-reading them and using the illustrations to teach myself how to draw birds.

I finally met the world’s greatest gooseman at Slimbridge in October 1952, but there were few wild geese on the Dumbels. Time in Kenya produced Spur-wings and Egyptians, but they were gaudy, lacking any music. At long last, in 1954, I went up to Cambridge, its famous bird club, the Fens and the Wash. Surely the next three years would bring me at least plenty of Pinkfeet?

They did and they didn’t, because a run of milder winters and agricultural change had disturbed ancestral haunts. I ticked a few off, but where were those exhilarating “morning flights” and “dawn choruses”?

Even long day trips to Slimbridge collected more fog than geese and the big birds continued to tantalise me. Eventually, blessed Unilever decided that I could do something for Wall’s Ice Cream at Gloucester and I ended up living a fast 18 minutes away from the Severn’s goose ground and thousands of Russian Whitefronts. Not just from the hides, but also from freezing hedges, I spent three winters among them, producing odd Bean, Pinkfoot, Greylag and best of all – annual Lesser Whitefronts, not to mention the occasional black goose too. Thus my 25-year apprenticeship was over and I was ready for grey geese anywhere!

Nowadays the auto-mobility of modern birdwatchers would make nonsense of such a long and erratic study, while the conservation of wetlands followed by some remarkable hide-building has provided us all with some instant goose theatre.

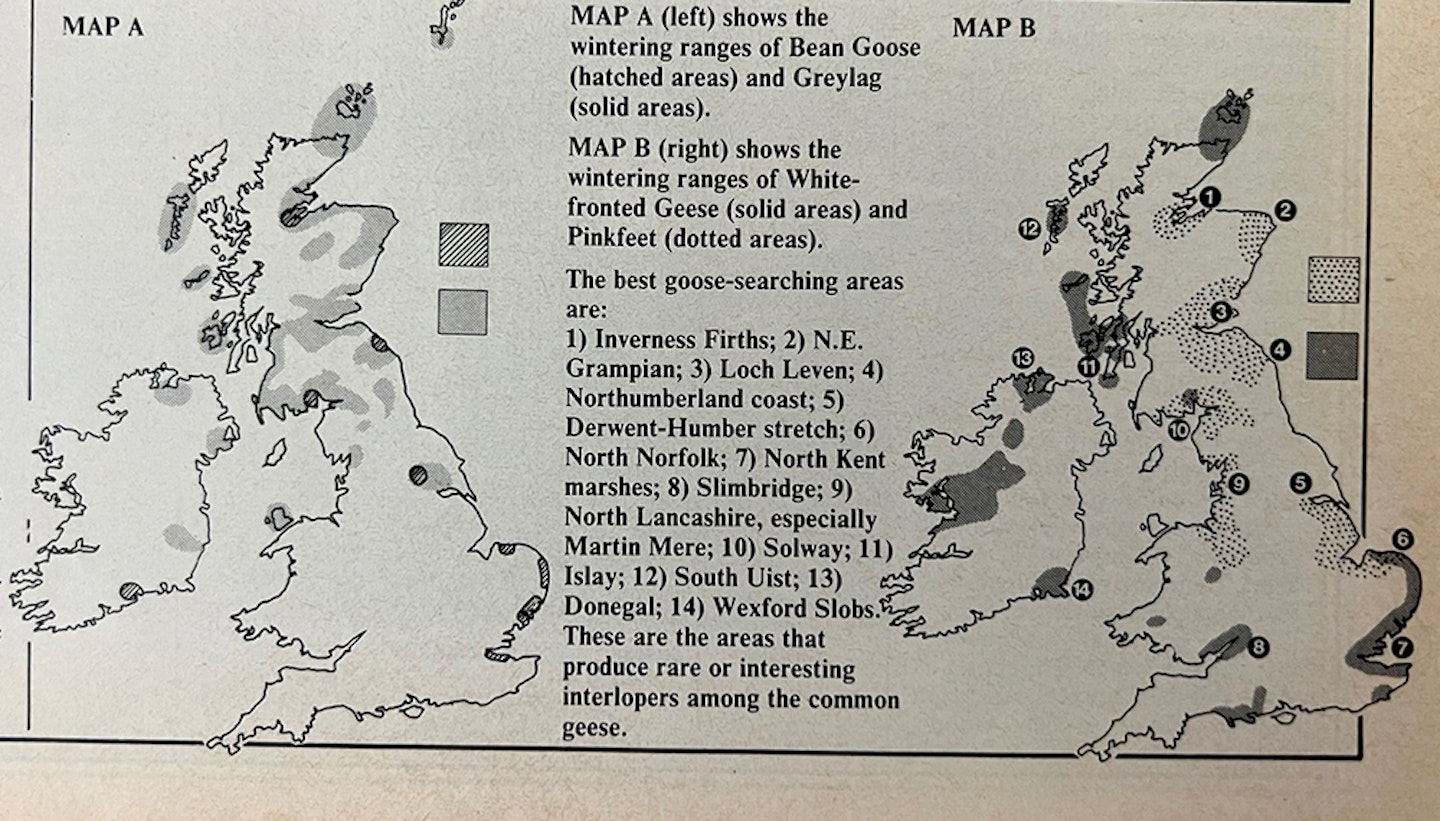

The maps show the main ranges of the four common species. Away from their regular haunts, grey geese can appear almost anywhere, with overshooting in autumn and early winter, westward movements to escape Low Country ice, eastward departures and straggling in spring all producing surprise occurrences.

A bit unfortunately, the increasing feral populations of Canadas and Greylags tend to mask these events for the inexperienced. It is possible to see parties of geese from any motorway at any season. So, you must take care not to be duped in the periods when truly wild geese are likely.

Even more annoyingly, the long history of keeping wildfowl as decorations on lakes has produced another increasing band of full-winged wanderers. You must understand that these do not just hedge-hop from collections. Some of the Slimbridge Snow Geese have reached France and both my recent counties have had other Snows, Greylags and even Lesser Whitefronts strolling round them.

Finally, and quite excruciatingly, both wild and feral geese hybridise freely. Be warned that their offspring can be very confusing; they arise not just between the members of the grey genus Anser, but also between them and the black tribe Branta as well.

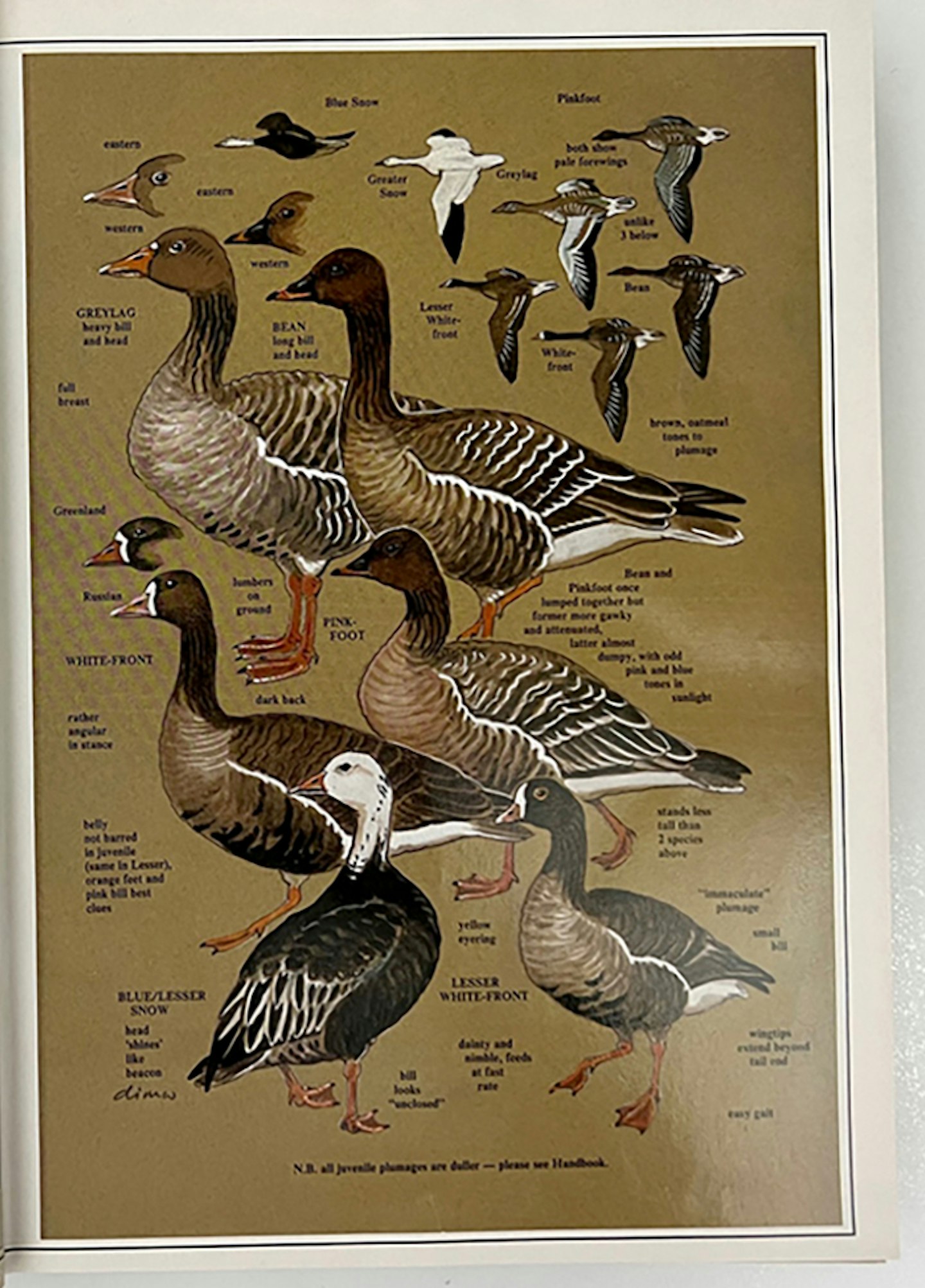

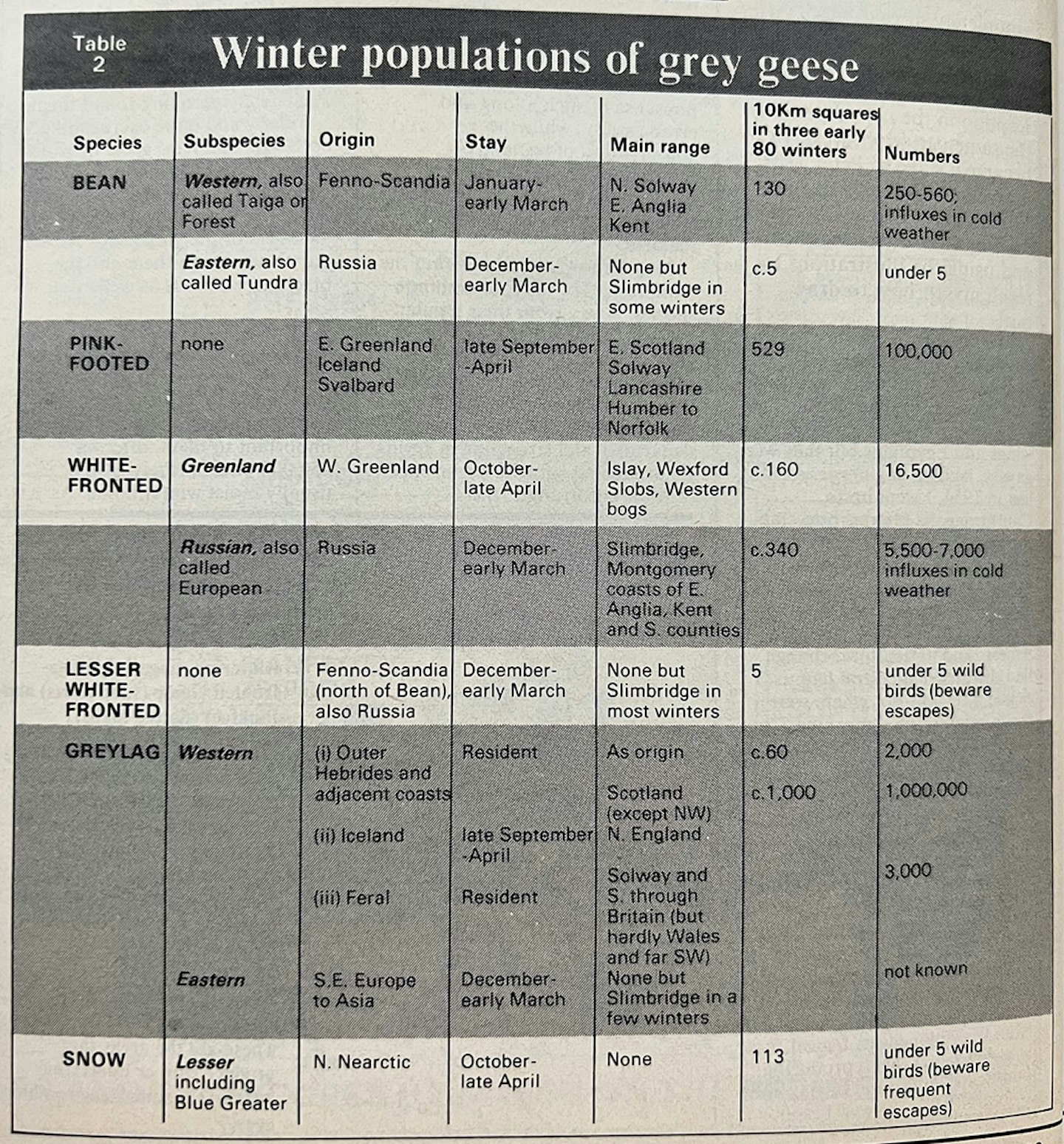

Right, enough of grey goose traumas. Let us get back to the big birds in the natural state. Britain and Ireland are very important to them, offering 250,000 birds a rarely frozen, usually moist winter home. As Table 2 shows in more detail, two species are common. Western Greylags occur in a quarter of our land and Pinkfeet in an eighth. The next most numerous is the Whitefront, with its Greenland contingent in the west and its Russian legions more in the south-east. Together the two races almost match Pinkfeet in total scatter, but for some reason, they shun eastern Scotland. Whitefront flocks visit highly traditional, grass marshes and bogs and the Russians still do not glean crop fields like other greys.

Far behind the three common widespread species – with five subspecies and seven discernible origins – come the Bean, Lesser Whitefront and Snow.

More than a century ago, the first was much commoner between the Solway and Northumberland but somehow it lost its place to Pinkfeet and Greylags. There are some signs of Beans returning to East Anglia. Certainly the Yare marshes form the nucleus of its winter presence.

The Lesser Whitefront and Snow are true rarities, their normal migrations respectively a half-continent and a whole ocean away. Nevertheless a few of the lost souls take up with our common species during post-breeding dispersal and are then “dragged” onto our goose grounds.

Lesser Whitefronts travel with both Western Beans and Russian Whitefronts, and Snows follow Greenland Whitefronts and Pinkfeet. So if your one is in a big flock of those carrier species, you have a bit of a tick.

A good rule in goose watching is always to search through any big flock with absolute care, since not only the rarities but some wandering commoner may be hiding within it. Such effort is essential to spying the subspecies listed in Table 2, with Russian Whitefronts bringing Russian or Tundra Bean and even the huge, pale Eastern Greylag.

Beware, however, the ever-present danger of an escaped bird, of which the most beautiful but also most disappointing is the Ross’s Goose, a tiny sibling of Snow. Two joined the Loch Leven grey geese in the 1960s and caused many dashed hopes.

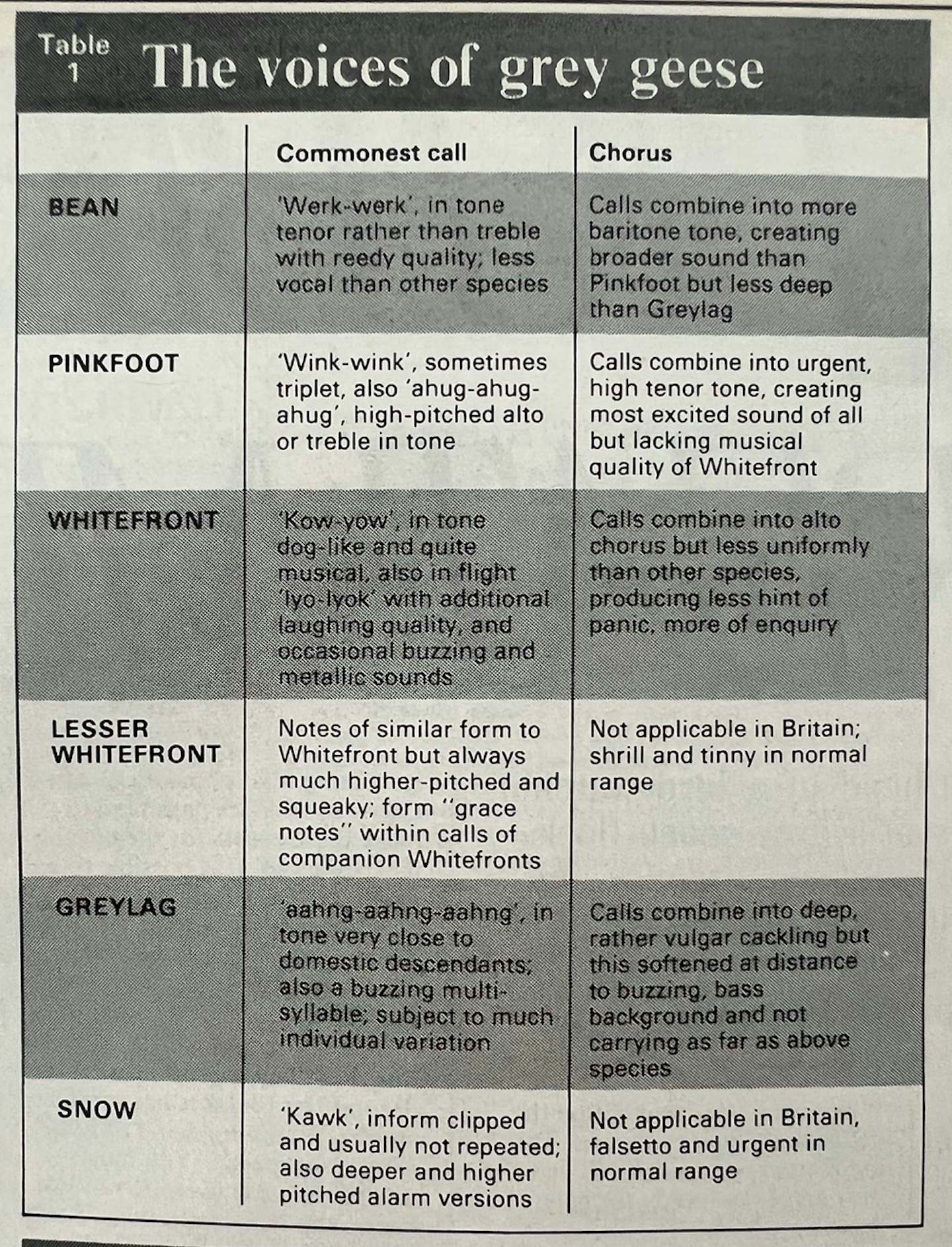

Geese may be mere noisy honkers. To mine and many others, they are the most exhilarating conversationalists of the bird world. On the ground, talk, bicker, challenges and flight signals come from all parts of their flock; in a flush, louder calls quickly assemble into an astonishing crescendo of alarm, possibly the careless observer’s only clue to their identity, and on flights to and from roosts and feeding grounds, calls frequently break out to maintain contact and add excitement to their marvellous “whiffling” descents.

Only when migrating in good weather or snoozing on a safe roost are grey geese at all quiet. With practice, the calls of grey geese are separable and Table 1 paraphrases the classic texts upon them. Remember, however, that at least some ganders and all juveniles have different inflections. With the end of punt-gunning and a reduction in regular wildfowler numbers, grey geese have become noticeably tamer but they still make a difficult winter quarry. In close hunting (for binocular views), you should if possible start “uplight” but “downwind”. Use every bit of cover (yes, even a wet ditch!) and never, never rush the last hundred yards. There is nothing worse than drenched wellies and soaked legs in return for a thousand goose bums going away!

If a long muddy trek is not for you, you don’t have to be satisfied with just reserve visits. The modern car is an excellent stalking horse. Add a modern scope and you will be able to see grey geese without leaving your seat.

Mind you, to crawl to within 50 yards of 2,000 Russian Whitefronts and, next, to realise that the nearest, neatest one is a Lesser – now, that’s a memory that will never fade. The choice is yours but there are real benefits in a proper wild goose chase. Good luck.

-

This article first appeared in the January 1989 issue of Bird Watching. Populations of some species have changed to an extent (Lesser Whitefront keeps getting rarer, Greater Whitefronts also less widespread and numerous, Pinkfeet doing well), and Bean Goose has been split into two full species, Tundra Bean Goose and Taiga Bean Goose.