Spotlight on winter owls

December 1988

BRITAIN and Ireland have only 10 of the Western Palearctic's 17 owls and five of those are rare, so your apprenticeship in these ghostly, nocturnal raptors has to start with the common species. Here IAN WALLACE starts your lesson on their identification.

Owls make for special birds that always thrill and regularly infuriate. Mainly nocturnal, sitting tight, flitting or wavering away without warning, disappearing into dense cover and without regular alarm calls, they make hard targets, all too briefly gone from eye or glass.

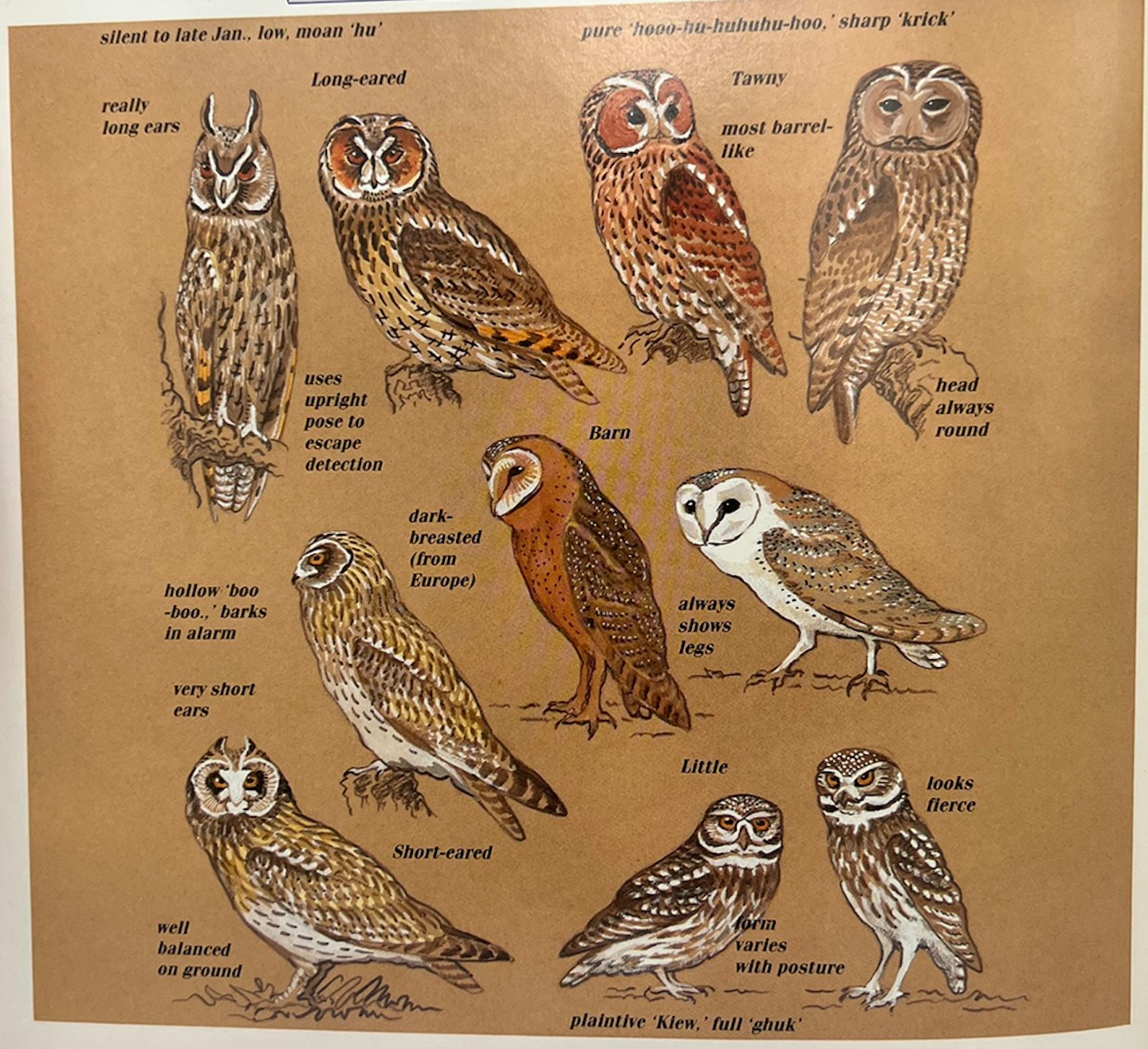

Furthermore, getting to know them well is a task of years, not days. It must include study of size and form, flight action, plumage colours and patterns, and songs and territorial calls.

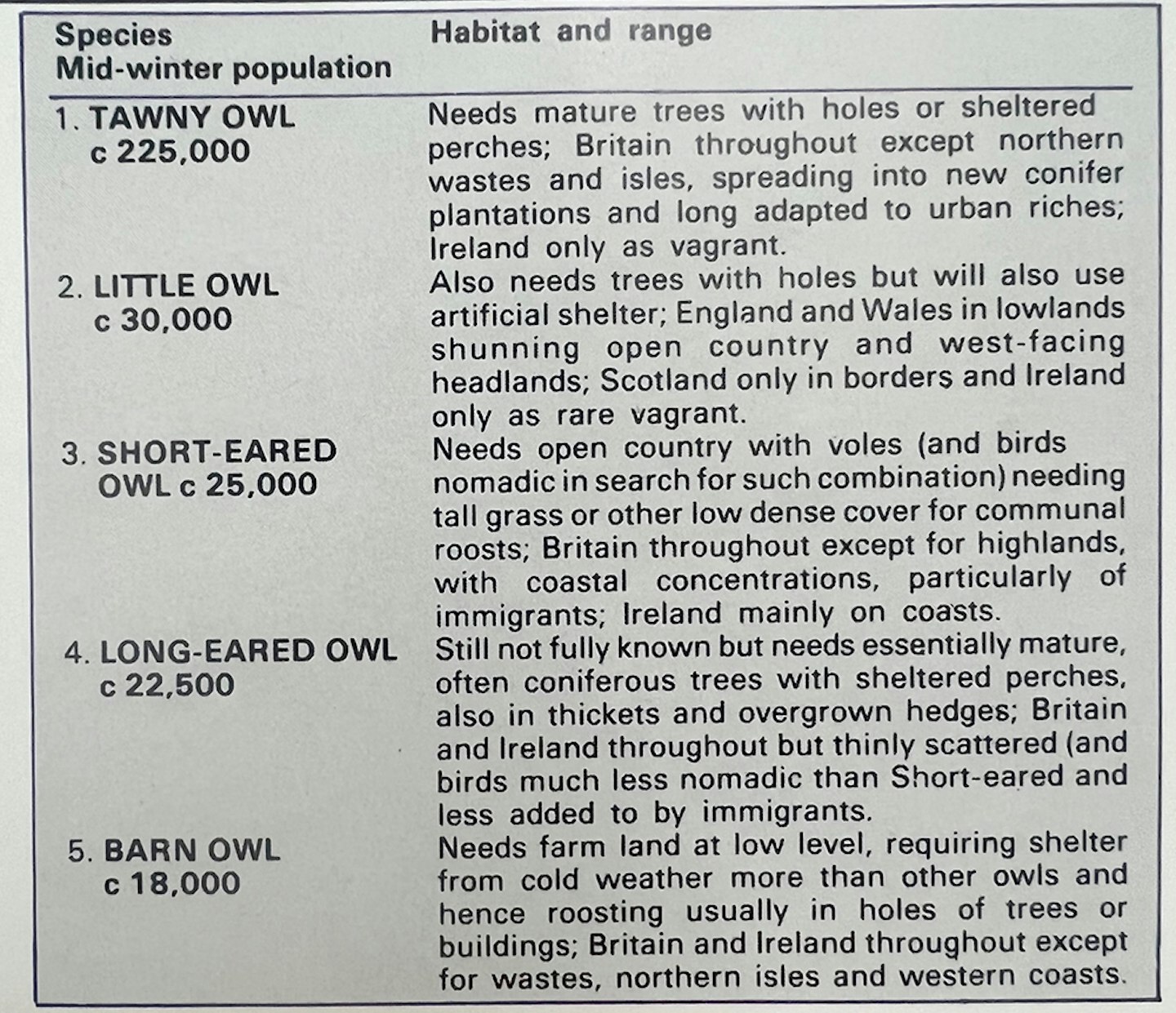

Before we get into the hard work, let us establish the “order of likely batting”.

The figures that I have given above are the mid-points of the BTO’s Winter Atlas estimates but the actual numbers of owls in winter can vary widely, with sizable immigrations in autumn or hard weather swelling the contingents of the two “eared” species, and heavy losses from starvation hastening the sad decline of the Barn in our lands.

The order of numbers suggests that eight Tawnies will come our way before any other owl. The fact is that birds do not always conform to such ratios. In my last two study areas, Littles have been more viable than Tawnies – but not more audible and in the last really severe winter, it was Short-eared and Barns that led in sightings. So, you will have to be ready for any of the quintet.

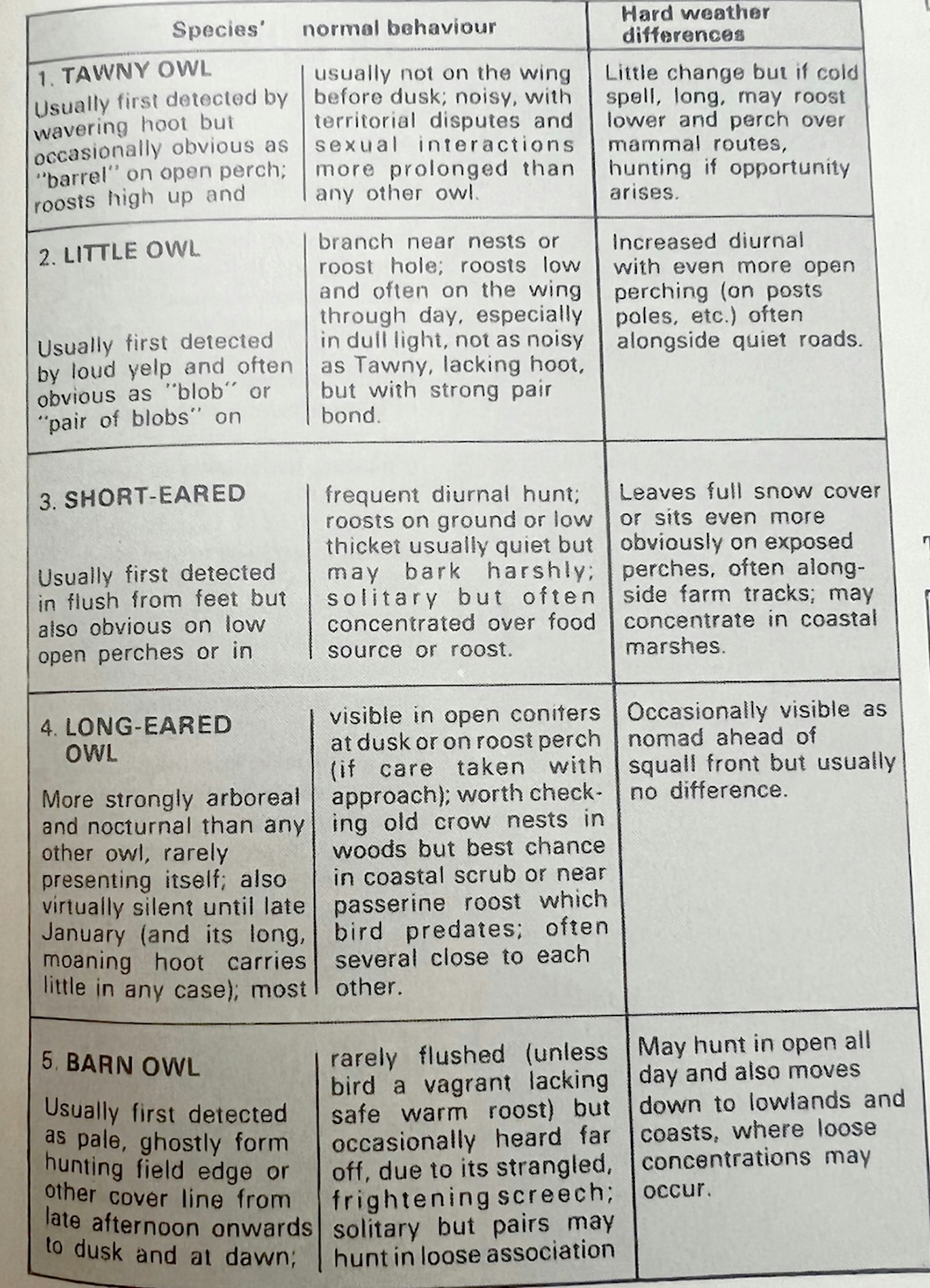

Let us now assess owl behaviour in winter:

Here we see more fully why the ratio of winter owl numbers does not translate readily into a ratio of winter owl visibility. Owl behaviour is not all “grab mouse by the light of the moon”, and by balancing habitat preference against behaviour, you can learn to judge where your owls should be, and hopefully are.

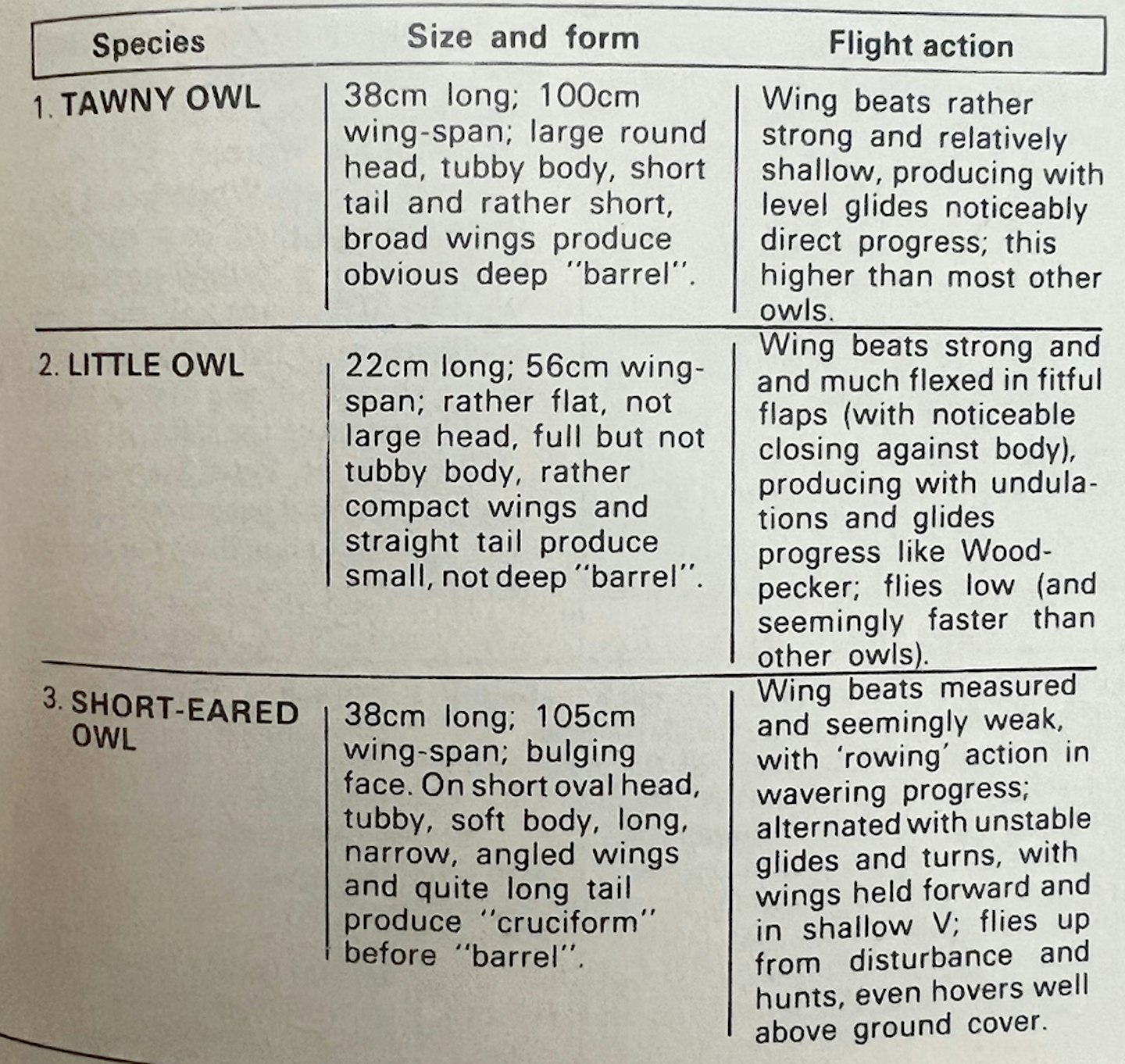

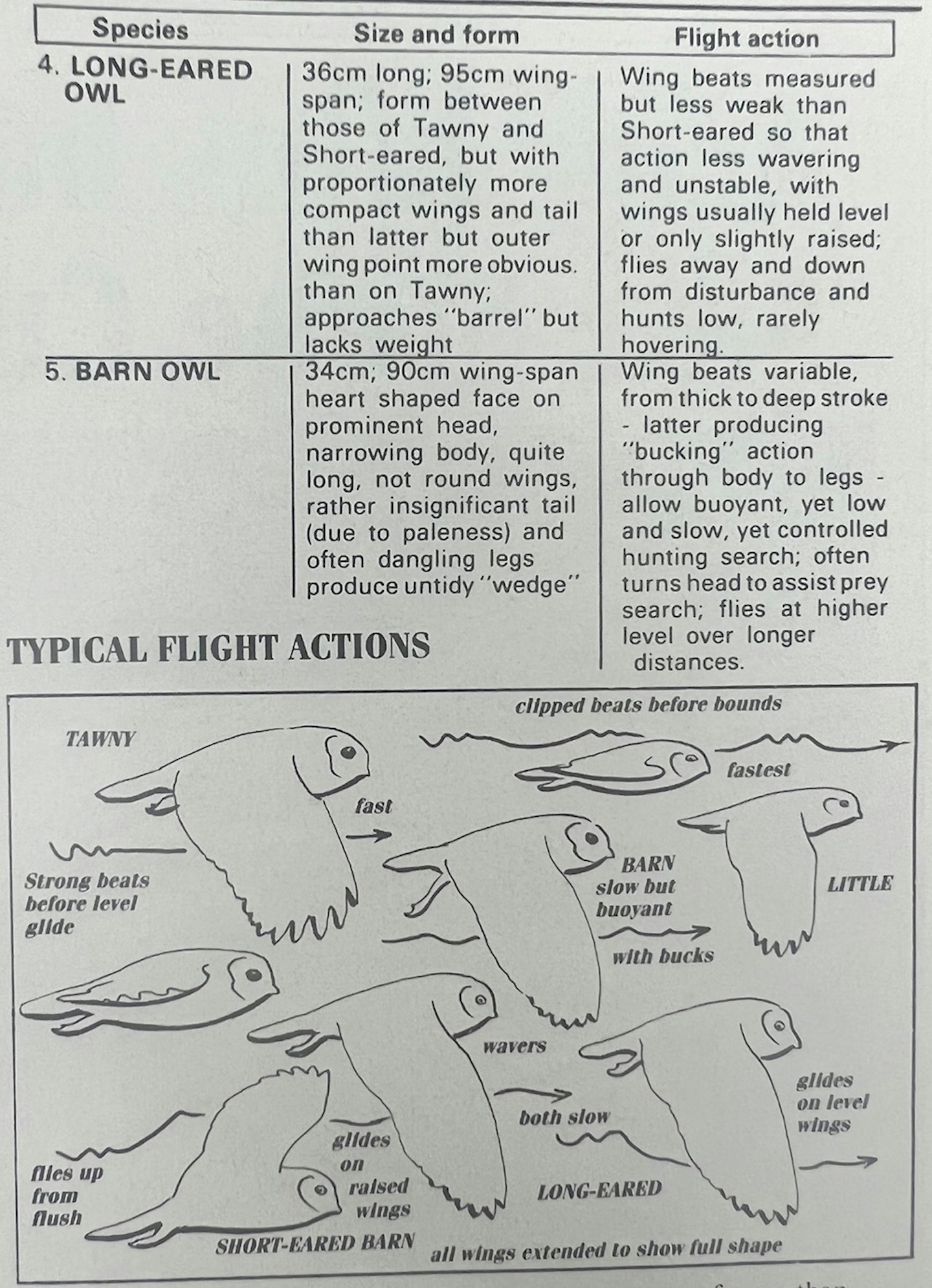

Alright, now let us assume that we have found an owl and flushed it. The snag is the lack of light and the quickness of the view. So concentration on size, form and flight action is essential:

Summarising the above is dangerous, but in conjunction with the earlier analyses, your focus on owls should be getting sharper. That small, bounding one is probably Little (but remember that Tengmalm’s is not impossible); that less small floating ghost really has to be Barn (for Snowy is really big, almost Buzzard-like) and that bulky barrel that glided directly really is Tawny. The difficult pair are the two eared species, but the occasions when they are in the same habitats (other than as

This leaves us with owl plumage and a further study of owl voices. The first of these subjects can cause total blindness, because owl feathers are among the most intricately patterned of all birds, while their colours can in poor light (or if starkly illuminated) appear to be similar.

Thus looking too closely at owls or their illustrations can be confusing and it is better to isolate the most striking characters. Once again you can spot the troublesome pair of the eared species. So do not forget to note form and flight while you are straining for plumage.

Last but not least come owl sounds. Your field guide will have the commonest calls, but you should be aware of more than these, for most owls have extensive vocabularies and so utter many audible clues. There really is no short route to knowing them and therefore I have to recommend that you read the ‘Handbook’ or ‘Birds of the Western Palearctic’ texts, and also do all that you can to learn the voices of Tawny and Little well in your local gloom. Remembering too that some calls are seasonal, familiarity with the utterances of the two most vocal species is the only safe basis of voice identification. I have added some transcriptions to the plate figures.

If by now you are fired with enthusiasm for owls, can I ask a favour? Please try to find and study Long-eared. It is a truly beautiful and still mysterious beast and worth real care and attention.

Two last hints. Firstly, winter really is a good time to start your owl studies. Not only are the leaves off most trees, but also dawn and dusk fill relatively more of the available day. Secondly, remember the habit of small birds of mobbing owls, and do not pass up any opportunity to investigate the noisy gatherings that assemble to abuse the secret raptor. Get close (quietly) and you could be treated to both tits and wrens fussing around the owl, and even Mistle Thrushes dive-bombing it!