Winter entertainers

November 1988

THE seven species of breeding tits represent under four per cent of the still bulging British List of passerines, but their winter numbers of about 30 million approach 20 per cent of the small bird mass. Here IAN WALLACE introduces this entertaining group of birds to you.

To the emergent birdwatcher, the tits are fairly easy quarry. Indeed, I sense apart from a few real fans, most observers regard them as “lesser” birds, but the truth is that they are a sparkling bunch, with great vitality and still some mystery.

In the Holarctic (the zoogeographical area covering the whole of Europe, North Africa, North Asia and North America), there are about 30 tits in the genera Parus, Remiz and Aegithalos, but in Western Europe, only nine of these occur. In the post-Ice Age reoccupation of our lands, seven got back to Britain and four to Ireland – a strong performance compared to other passerine families – and overall about 10 million pairs of breeding tits produce an early winter population of 30 million surviving adults and young. With their density apparently as high as 800 birds to a square kilometre, they form a fifth of our wintering passerines.

What is the secret of their success? For a start, tits are bright and adaptable beings, and six of the seven are omnivovous, exploiting many food sources at will.

Next, they have a high breeding potential, with their usually single clutches often numbered in double figures – even 24 when two hens are involved. Family after-care is strongly developed, persisting longer than in most passerines and foretelling their chief winter strategem for survival. This is the forming of roaming flocks of up to 40 birds that reap and glean (and glean again) every food niche in wood and scrub cover.

Piebald beauty: The most unmistakeable member of the tribe is the Long-tailed, a tiny ball of whirring fluff trailing a very long, tight-packed set of tail feathers. Its “stirrup” and “tupp” calls are lower pitched than in other tits but carry well. Its plumage is basically piebald, with softer rosy-grey hues except on the boldly striped head and tail. A dark bead of an eye and a tiny black bill set off a gentle face. Long-tails can be as tame as Goldcrests and there is no more magic experience than to have them flitting round your head. Unlike the commoner tits, Long-tails are shy of gardens (this has since changed – Ed.) – except in hard weather – and I find them most in deciduous tree canopies, open thickets and old orchards, searching diligently for their insect food. Their mild winter numbers approach 100,000. But in cruel weather with glaciation, they can be almost decimated.

Scarce Cresteds: The next most unmistakeable tit is the Crested, a quite chunky, behatted bird with the build of the Blue Tit. As distinctive as its spiky, black and white-splashed crest is its rather angry, purring trill. This call is usually the first signal of its presence because its plumage, unlike the other tits, is quite cryptic, merging with faded bark of branch or trunk. In winter, they forsake conifer canopies, frequently adopting a Treecreeper-like search of lower tree heights or even coming to ground cover and Highland bird tables. The Scottish subspecies is adapted to Scots Pine but, in recent decades, it has also entered foreign conifer plantations, spreading into five Scottish counties between north-east and west of its Rothiemurchus stronghold. With no more than 3.600 alive in winter, it remains scarce. I have found my Cresteds most easily by rapid searches of pinewood edges and paths, with ears cocked.

Great Tit boom: The biggest and most intensely coloured British tit is the Great, with rather finch-like behaviour intensifying in winter as it becomes a ground forager, particularly for beech mast. Its plumage colours are vivid, green on the back, black and white on the head and its black bib, extending into an obvious division of yellow body – all well exhibited on its lengthy, big-headed and full-tailed form. The Great’s vocabulary is the widest of all our tits. Start with its Chaffinch-like “tink, tink” and then learn the other calls in the field is the only safe course. The Great has prospered in recent years and the BTO estimates its winter population at 10 million or two-thirds that of the Blue. I doubt that ratio. My own linear counts suggest that it is only 20 to 40% as common as Blue. Even so, it enters gardens freely and adapts well to even urban life.

The entertainers: The next most colourful tit is the tame and endearing Blue, with its small but chunky, seemingly square-headed form strikingly splashed blue on the crown, nape, wings and tail highlighting its basic pattern on white face, green back and yellow body. In another long vocabulary, the chief call is a soft but merry “tsee-tsee-tsee”. With its almost catholic habitat range, the Blue will be almost certainly the first tit that you see. Hang up some peanut bags and you could be deluged by them. Up to 200 a day may visit such freefood sites. In recent years, the Blue has declined slightly, but our lands still hold about 15 million in winter.

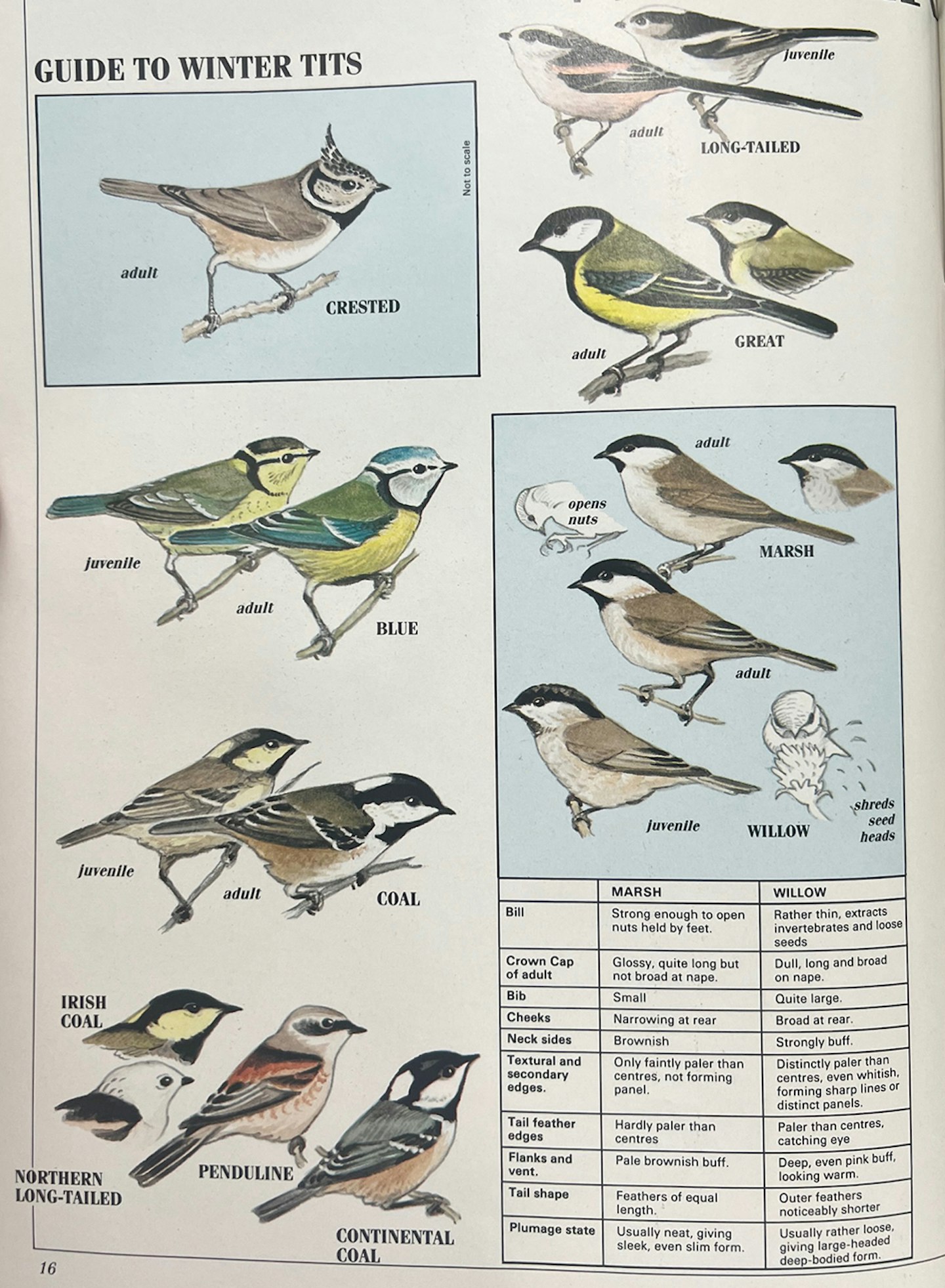

Now comes the trio of black-capped tits, namely the Coal, Marsh and Willow, and with them the difficulty of field identification increases sharply. Although not shy, they are all less ubiquitous than the three common species discussed above.

In England, four species – Blue, Great, Coal and Marsh – bond together more often than not, combining their specific skills to exploit every food source. Furthermore they are frequently accompanied by Treecreepers, Goldcrests and Wrens, and less often by redpolls and Siskins.

Thus a tit flock may contain several surprises and with our winter fields these days so clean, and thus so barren of open country finches and buntings, their woodland congregations present a real luxury of winter passerines. Get in amongst them and you may yet shed more light on the mysteries of Marsh and Willow or be the first person to see a Crested south of Speyside for nearly 50 years!

Frantic feeder: My favourite is the conifer-addicted Coal. In my opinion, it is the neatest (also smallest), most active, most decorative, best-voiced and most Scottish of the lot. Its winter population peaks at about four million, ranking as the third largest of the family. Seen close and low down, its white nape spot and wingbars are diagnostic but glimpsed in high canopy, its silvery yet sweet and excited calls – one written “cheereet”, very like that of the Yellow-browed Warbler – are by far the best clue. Its frantic feeding stems from its constant need to fuel its small, heat-losing frame. It is noticeably gregarious but sadly it does not visit gardens regularly, your first will be in your nearest evergreen wood, especially if it includes pines, spruce and larch.

Troublesome duo: Finally, we are at the pair of tits that have caused birdwatchers and ornithologists no end of trouble (and still do). They are the long-known Marsh and the 91-year old Willow. A puzzling comment? Well, the truth is that until 1887, our forebears did not distinguish between them and thought that all our fully black-capped tits were Marsh. Both species failed to reoccupy Ireland and have only southern footholds on Scotland. Furthermore, their relative numbers and habitat preferences in England and Wales are still debated. The BTO estimates their winter numbers as 200-400,000 Marsh and 175-300,000 Willow. Again I have my doubts about the ratio of these figures. In my Staffordshire study area, Marsh just outnumbers Willow 6:5, but in my East Riding patch, Willow eventually beat Marsh 8:5. Their chief behavioural difference in winter is the Willow’s quite marked tendency to follow leading lines like hedges and streams and move away from their natal woods. Could this sign of greater adventure mean that Willow will win the number contest in the end? Certainly the more local Marsh is declining, perhaps by 20 per cent in the last two decades.

The Marsh’s name is confusing, for it actually prefers dry, open oak and beech woods and only enters conifers if these are close to, or mixed with, deciduous trees. The Willow’s name is more helpful, for it truly favours damp woods and thickets and enters conifers freely. These habitat differences are not sharply drawn, however, and the two species do occur virtually alongside each other.

Spotting the diagnostic differences is not easy, but the chart may help. To see the marks, you have to get close and take your time. With distant birds, your only hope is voice. The Marsh’s common strident “pitchon” is diagnostic, being totally unlike the Willow’s grating “tchaa-tchaa-tchaa” and sibilant "eez-eez-eez”. Beware especially mistaking the former Willow call from the Marsh’s not dissimilar breeding season note “tchay-tchay-tchay”; both are nasal in tone.

Is this the end of British tits? Not by a long chalk, for they also contain a rare species – the Penduline, which has spread west in Europe and now strays to England – and eight Continental and one Irish subspecies. In 45 years in Britain and Ireland, I believe that I have seen seven of the latter in autumn and winter, and the chance of a different race adds real spice to tit watching. They are not improbable, for all the tits – except apparently Marsh – send out contingents of surplus young in good breeding years. It is over 30 years since a major irruption reached Britain, but most species still come as irregular autumn immigrants.

-

This article first appeared in the November 1988 issue of Bird Watching. Since then, first Willow and then Marsh Tits have suffered large and worrying declines, Crested Tits have continued to spread slowly from their stronghold, and occurrences of Penduline Tit have become more common.