The Yanks are coming!

October 1988

FIFTY years ago, the Handbook of British Birds did not list one (though it should have!) Then 37 years ago one reached Ireland. Three years' later, two definitely reached England. Nowadays, up to 40 North American passerines are found every year. This is the potted history of these Yankees vagrants in our lands. Here IAN WALLACE chooses six to paint and discusses their origins.

PAGE 233 of Volume 1 of the Handbook of British Birds ends with a footnote on the two Nearctic Wood Warblers reported up to 1938. Its square brackets – a clear signal of ornithological doubt – dismiss a Yellow Warbler in Durham in May, 1904, and a Black and White Warbler on Shetland in October, 1936.

They were branded as having respectively “most probably” and “probably” escaped from captivity, in spite of the fact that the four authors had accepted trans-oceanic flights for two redpolls, two ground buntings, one pipit, one nightjar and two cuckoos – not to mention 36 other non-passerines. So, they could be accused of behaving somewhat illogically.

Nevertheless, the rule was that no small insectivorous bird could cross the Atlantic. Accordingly, most of us ignored the “small Yanks” in the 1940s and early 50s, but they themselves eventually forced the issues out into the open again.

The seasons of the first full revelation were the autumn and winter of 1954, when Devon smashed the rule and produced a Yellowthroat in November and a Myrtle (now Yellow-rumped) Warbler at a bird table in the New Year.

These two pioneers – following a little-publicised corpse of a Red-eyed Vireo off Co. Wexford three years earlier – took the scales off all our eyes. One way or another, small, seemingly- delicate, passerines could cross “the pond”. But precisely how?

This question was much debated in British Birds papers and by the BOU. The famous accounts of Alan Durand, telling of fast liners swamped with avian as well as human passengers, provoked the theory of “ship-assisted passage”, and there were occasions of birds apparently jumping ship at sight of land. Certainly my first two Red-eyed Vireos, happily alive and kicking, coincided with a close pass by the ‘Rotterdam’ off St. Agnes, but there were other times when only slow cargo boats or no large boats at all accompanied arrivals. It was all very puzzling.

The weather vector that finally put an end to the mystery was the strong Atlantic tail wind of October 1968. It produced the first multiple and widespread “fall” of small Yanks, with two in Co. Cork, seven on Scilly and three more in Caernarvon, Dorset and Sussex. Belief in rapid, continuous trans-oceanic movement could be withheld no longer.

The slur of “ship assistance” was summarily ended, as in many cases its original carrier, the fast liner, had become banished to cruising. So came about the modern expectation of the double autumn miracle of small warblers or warbler-like birds that reach Britain and Ireland along tracks that run three to four thousand miles from both east and west. No other phenomenon has fulled the mass pilgrimages to our south-western headlands as much but, with the spread of observations elsewhere, the arrivals of Nearctic passerines have been noted throughout the length and breadth of our land masses. Judged by an American computer forecast, there are many more species still to appear.

Before returning to the question of why they come, I should clarify what kind of birds are involved.

None are closely related to the classic Palearctic vagrants in the old world tribes of chats and warblers. Surprisingly, they are systematically at least 14 families apart, being more closely related to buntings.

This position shows that they have evolved separately, with their general resemblance in form and behaviour to warblers a result of parallel convergence in response to similar habitat niches and food.

What makes most of them instantly distinct, at least as adults, are their bright, colourful patterns and rather restricted vocabularies.

This combination is lacking in their equivalents in the Old World, but it does echo that of our equally colourful and rather tuneless tits. In the whole New World, their total radiation into species is great, having produced 233 tanagers and allies, 120 wood warblers, 39 vireos, and 92 icterid species. But it is only their 40 most-northerly breeding members in eastern North America that meet within their long migrations the weather factors responsible for eastward vagrancy.

As anyone who has watched migration in North America knows, the small migrants regularly form true masses of birds. These can be seen not just at classic places like Cape May, but also at less fashionable spots such as the southern point of Nova Scotia. The birds are literally in all the bushes and can be observed heading out to sea to use the power of strong tail winds to speed their crossing to the West Indies and South America.

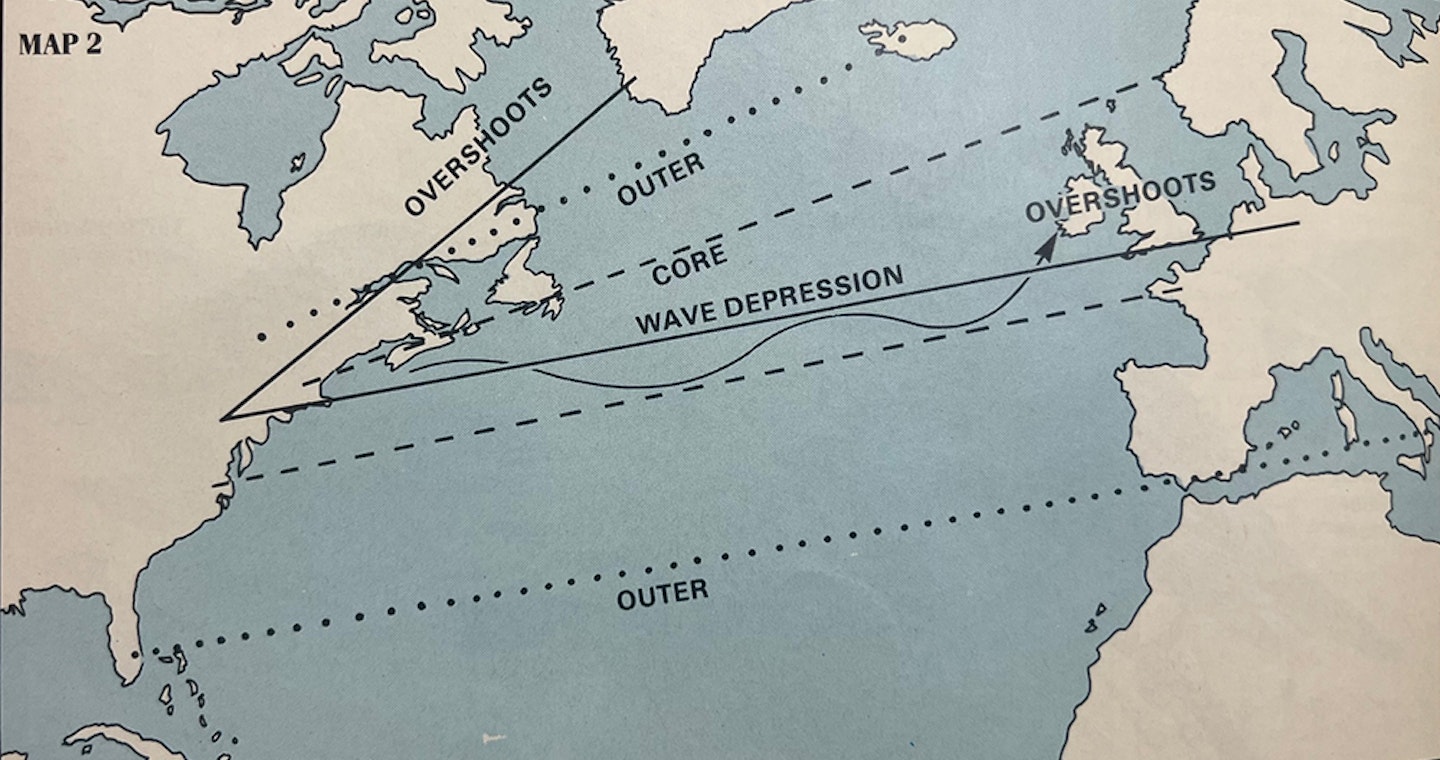

Along America’s East Coast, “poor” autumns for birds do not occur and, particularly in early and mid October, combinations of poor visibility – leading to disorientation – and wave depression producing fast easterly airflow, may divert large numbers of birds from their normal southward passage on and offshore to a perforce eastward drift (or better hurtle!).

The crucial factor is the wave in the wind for it produces sustained support to onward flight, unlike full hurricanes and slow lows, whose circulation actually produces useless loops in the wind directions. When the wave is relatively smooth and fast, as in the October of 1976 and 1985, up to 40 small Yanks can appear, but it does not follow that such birds have made a short crossing of the Atlantic.

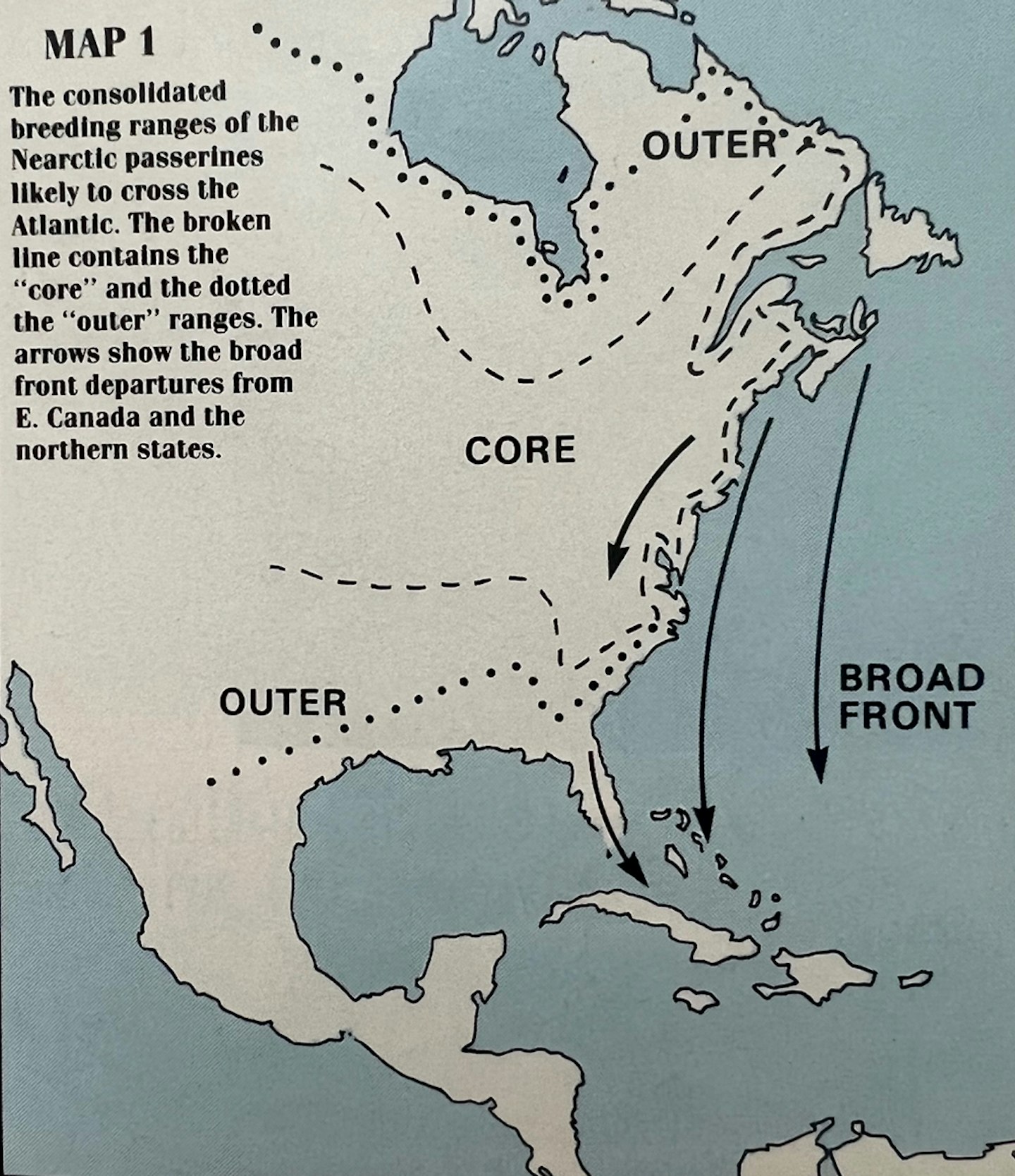

Analysis of weather maps has shown that the origins of most vagrants are probably within five degrees either side of the latitude of 40°N. It is not impossible that some birds stem from the Carribean Islands on an ENE, and not the more normal E by N heading.

To understand the whole phenomenon more fully, look at Map 1, which shows the common breeding range of the most regular species and their normal migrations. Map 2 plots the fans of westward vagrancy as indicated by European landfalls.

The vast majority occur in autumn, from September to November, but a few birds, mainly American “sparrows” also overshoot in spring.

There is one last mystery. How precisely do the birds keep going over as many as 4,500 watery miles? It may be necessary for them to sustain flight for two or three days and at combined speeds – from their own power and the windstream – of up to 100km an hour. Unfortunately, extensive radar observations have not been made, and we are left with the miraculous performances to wonder at.

Mind you, theirs are not the ultimate in trans-Atlantic crossings. Surely the prize for that must go to the Monarch Butterfly, which quite often appears among the small birds!

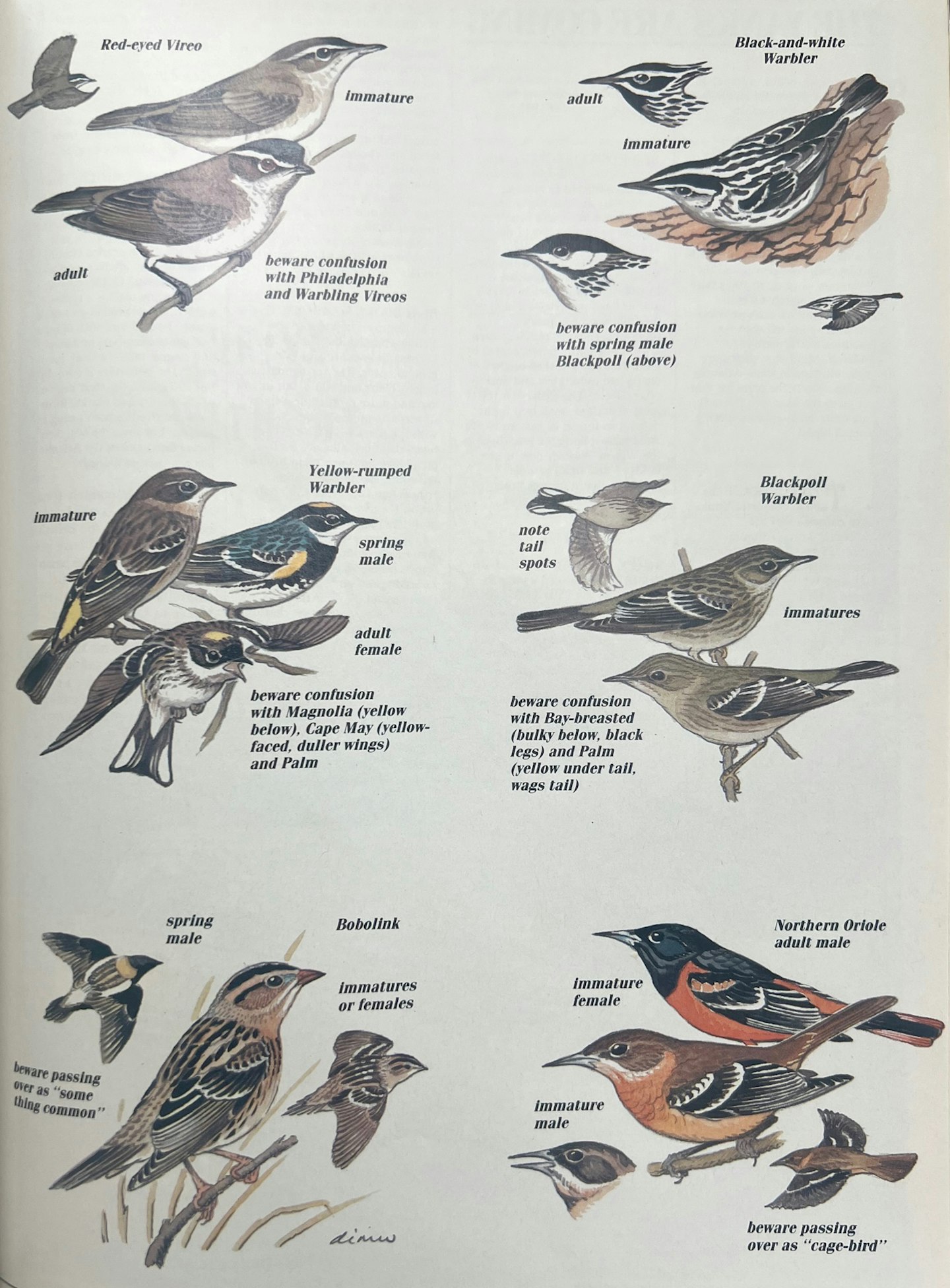

To illustrate the small, colourful Yanks, I have chosen six of the commonest transatlantic vagrants. These are the Red-eyed Vireo, to represent vireos; the Black-and-White Warbler, Yellow-rumped (Myrtle) Warbler and the Blackpoll Warbler to represent the wood warblers or parulids; and the Bobolink and Baltimore Oriole to represent the Nearctic blackbirds and orioles or icterids.

Their British and Irish records range from 10 to 35 each (up to 1986 or, better, in the last three decades) and any observer visiting our south-west facing promontories or islands can expect to be confronted with one, or several, as in the best-yet Nearctic autumn of 1985.

RED-EYED VIREO: This rather sluggish, but confident, passerine is much addicted to hunting caterpillars and the like in the leaf canopy and is likely in a brief glimpse to suggest one of the heavier Sylvia or Hippolais warblers, particularly the Garden. What instantly distinguishes it is its call (a strikingly nasal “chay”) and its head pattern – a blob of a bill followed by a dusky (immature) or grey (adult) crown, a white supercilium interrupted by a brown (immature) or bright cherry red (adult) eye and dusky- olive cheeks. The Red-eye is the most abundant small bird in the deciduous forests of eastern North America – taking the lead there as the Willow Warbler does in our lands – and small wonder therefore that it crosses “the pond" more than any other.

BLACK-AND-WHITE WARBLER: This is the ultimate zebra of Nearctic passerines, being entirely striped black or dusky and white in all plumages. Its general character recalls those of warbler, Nuthatch and tit, as it feeds more on branches and trunks than in foliage. As a vagrant, it is usually silent but its appearance is utterly diagnostic. Amazingly, one was found in Norfolk in December, 1985. Normally it is a south-west/October bird.

YELLOW-RUMPED (MYRTLE) WARBLER: Here is a real sprite, highly arboreal with superbly- developed fly-catching skills (when needed). With white tail-spots, a sulphur-yellow rump and double white wing-bars, in any plumage it immediately catches the eye. Splashed with more yellow on crown and breast sides, black- faced and chested but also white- throated in adult male breeding plumage, it is a delight. Hardy and thus able to winter as far north as New York and Devon, the Yellow- rumped started off as the commonest of its group but it has since been overtaken by the next. It calls “check” loudly.

BLACKPOLL WARBLER: This is a bit dumpy compared to the Yellow-rumped and less active, keeping to lower foliage and ground cover. The spring male is largely black and white, but its full cap and more mottled, less-lined upperparts prevents confusion with the Black-and-White. The female and juvenile are far less distinctive but once again brilliant tail spots, sharp wing feather fringes and two white wing-bars set off the rest of their rather pipit-like plumage. It is abundant on the east coast of North America, breeding in coniferous forests all the way to North Labrador and pouring south through and off the Atlantic states. Again, no wonder that it is the second commonest waif, even appearing in small falls like the Red-eye.

BOBOLINK: A strange half- sparrow, half-quail of a bird, without a direct Palearctic counterpart. Always in thickets or rank fields as a vagrant, it calls “pink” in flight and its warm buff and black-lined plumage and pointed tail-feathers remind me of an Aquatic Warbler – bar its heavy beak – or a Yellow- breasted Bunting in immature plumage. A bit of a nomad in the Eastern States, and South-East Canada, it forms large post- breeding flocks and it is from these that ours have strayed.

BALTIMORE ORIOLE: This bird is the largest of this sexlet, being the more common of North America’s two arboreal icterids east of the Mississippi. It is shaped like a small long-tailed Starling and in no way invokes confusion with the classic Golden Oriole. The spring male is a spike-beaked, black-headed-and-backed orange-bodied bird with orange and white wing-bars and black and orange tail – a truly gaudy sight. The immature is a lot duller but still sports the clear beginnings of its colours and marks. Birds have occurred in both spring and autumn but since the 60s, their initial burst across the Atlantic has not been sustained.

I am not desperately fond of Nearctic birds. It was fun to be in on some of the British “under fives” but I have never hunted them with the passion that I still seek Palearctic vagrants on occasion. Even so, I have to say that they are better in their own continent and have given me some splendid days in summer and autumn. Just one bucket-shop ticket to New York and in Central Park and at Jamaica Bay, you can be swamped in their colours! And those of Monarch Butterflies, too!

This article first appeared in the October 1988 issue of Bird Watching.