Broom handles Boots and rare Whitearses

September 1988

Broom handles Boots and rare Whitearses

An odd collection? Not so as lan Wallace explains below. Hot on the heels of the south-west Asians that he described last month, another five southern rarities get his attention.

What on earth can a ‘broom handle’ have to do with a bird? Well, it was Scilly veteran Bob Emmett's description of the bill on a Olivaceous Warbler that arrived on St Agnes. And ‘boots?? A short word for the appearance of the scaly legs of the Booted Warbler. And ‘Whitearses’? Supposedly the Anglo-Saxon group name for Wheatears or in the context of this essay: the Desert, Black-eared and Pied Wheatears.

In order of mention, these five birds have British and Irish scores (to 1986) of only 14, 22, 24, 39 and 12 records. Thus they qualify as rare, but not extremely so. Their combined score has doubled since 1970 [and considerably multiplied by the 2020s].

Why then do they all form particularly interesting targets for birdwatchers? Because their breeding ranges stretch in combination all the way from Iberia and north-west Africa through the Mediterranean and Middle East to Mongolia a remarkably far-flung source of vagrancy. Because also the five species had radiated into two to four races each, to total 14 – a tantalising challenge to the field observer and one which should not be ignored, since 11 of the 14 are known to have reached Britain!

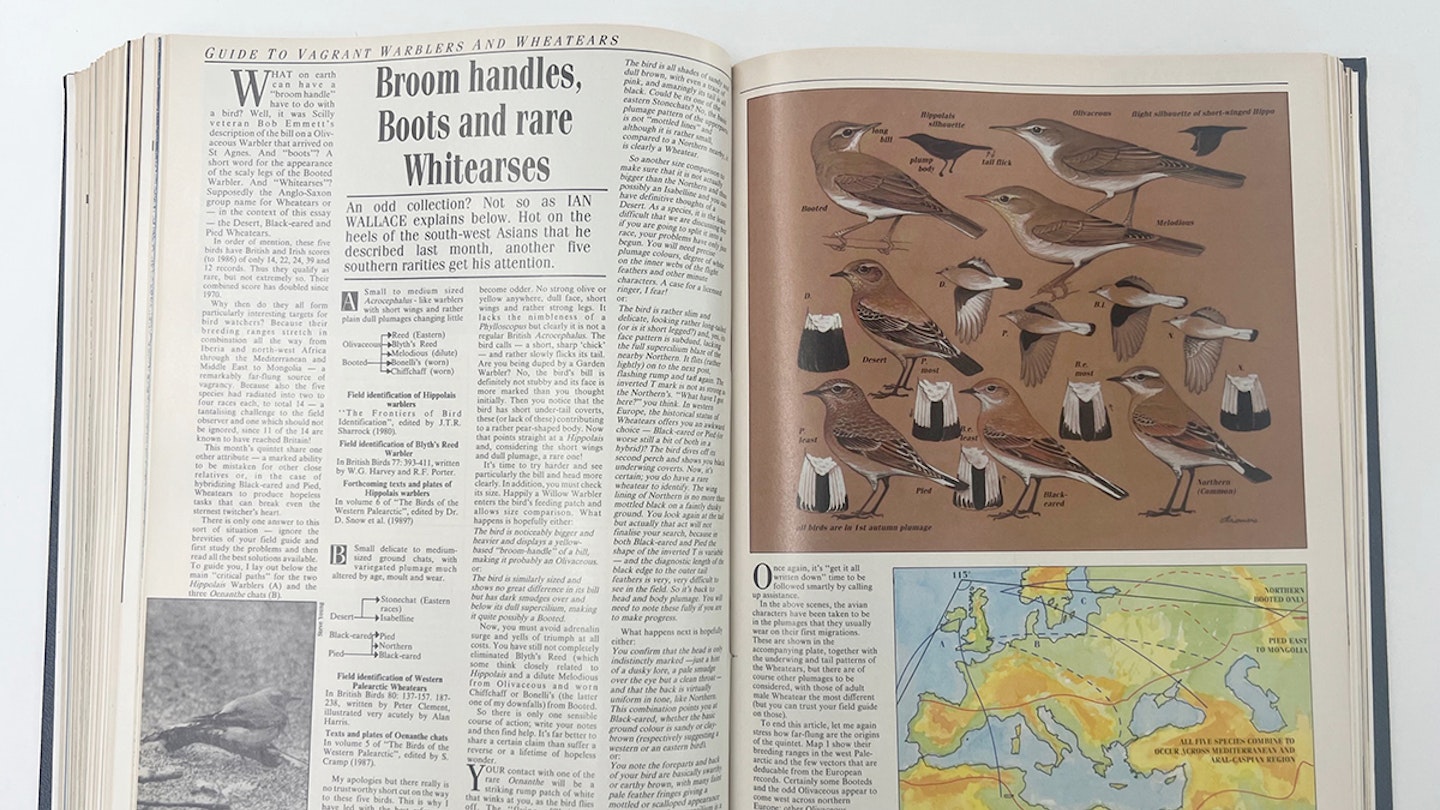

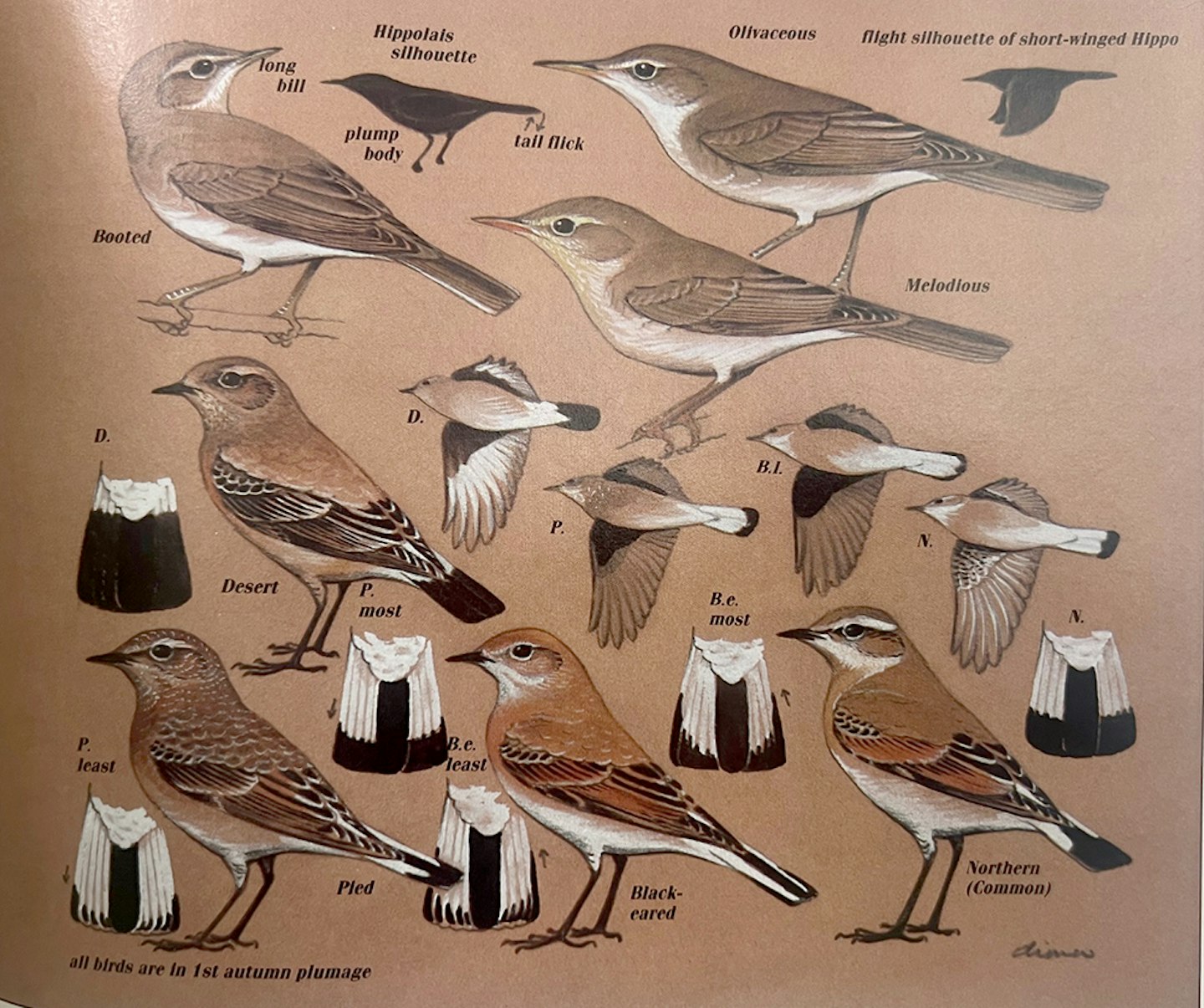

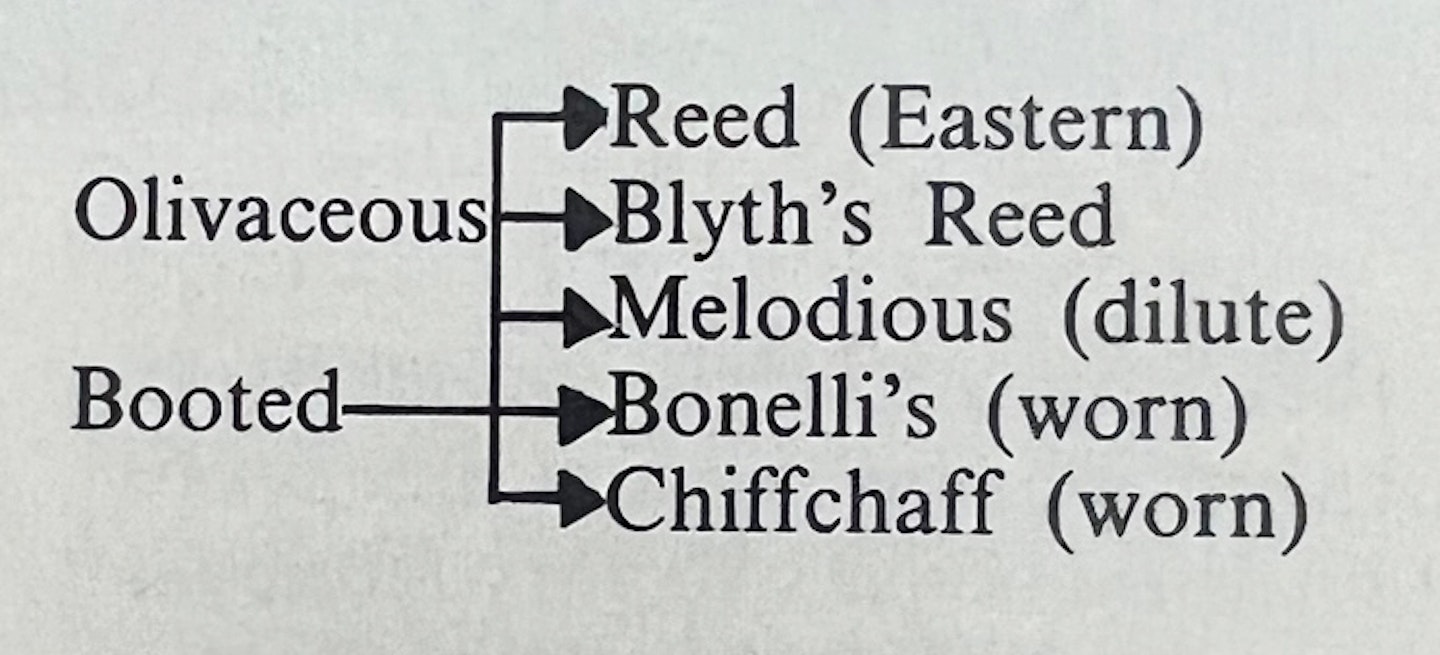

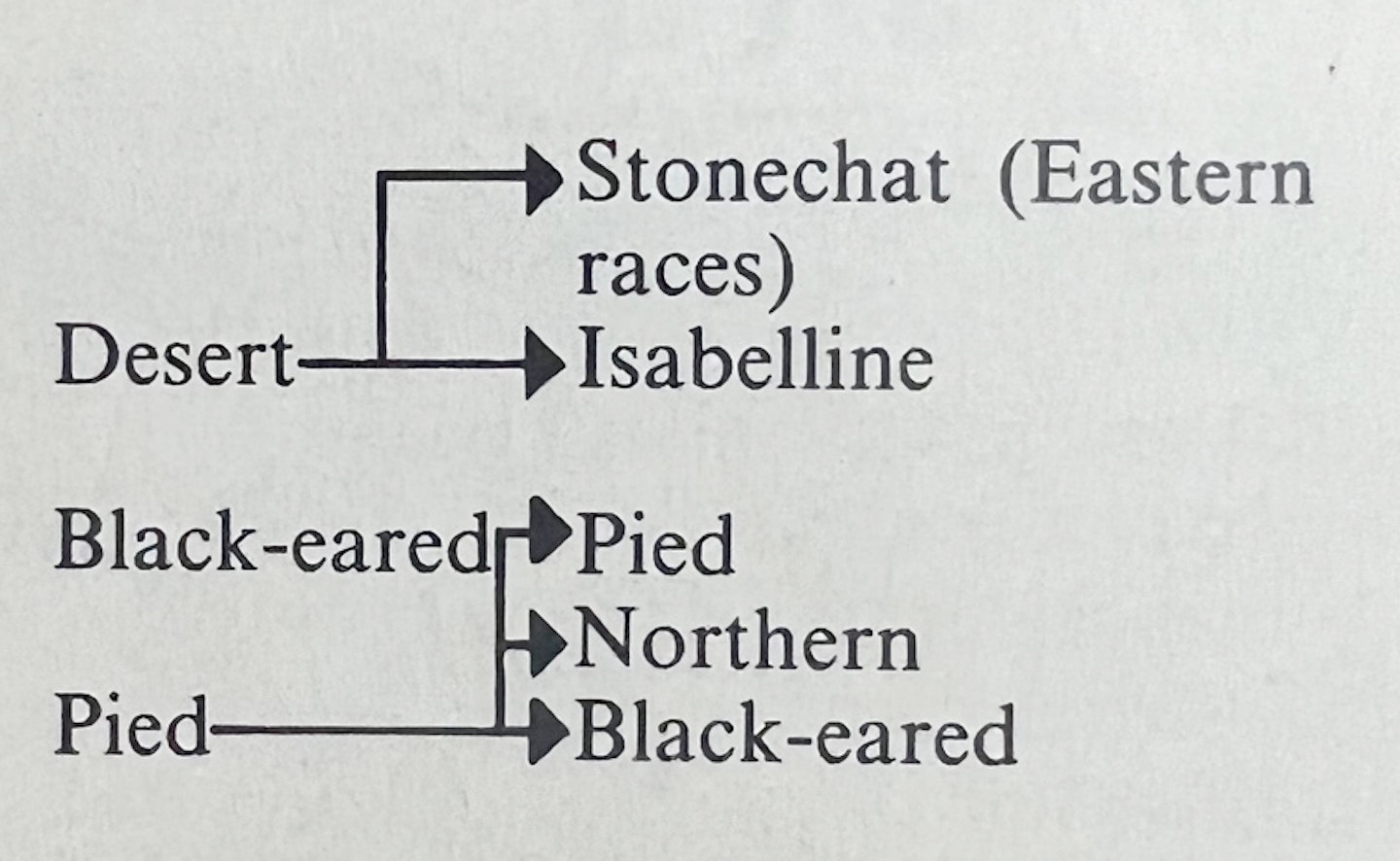

This month's quintet share one other attribute – a marked ability to be mistaken for other close relatives or, in the case of hybridizing Black-eared and Pied Wheatears to produce hopeless tasks that can break even the sternest twitcher's heart. There is only one answer to this sort of situation ignore the brevities of your field guide and first study the problems and then read all the best solutions available. To guide you, I lay out below the main ‘critical paths’ for the two Hippolais warblers (A) and the three Oenanthe chats (B).

A

Small to medium sized Acrocephalus-like warblers with short wings and rather plain dull plumages changing little:

References: Field identification of Hippolais warblers ‘The Frontiers of Bird Identification’, edited by J.T.R. Sharrock (1980). Field identification of Blyth's Reed Warbler In British Birds 77:393-411, written by W.G. Harvey and R.F. Porter. Forthcoming texts and plates of Hippolais warblers In volume 6 of ‘The Birds of the Western Palearctic’ , edited by Dr. D. Snow et al. (1989?)

B

Small delicate to medium- sized ground chats. with variegated plumage much altered by age, moult and wear.

References: Field identification of Western Palearctic Wheatears In British Birds 80: 137-157. 187- 238. written by Peter Clement. illustrated very acutely by Alan Harris. Texts and plates of Oenanthe chats In volume 5 of ‘The Birds of the Western Palearctic’, edited by S. Cram (1987).

My apologies but there really is no trustworthy short cut on the way to these five birds. This is why I have led with the best references and not the comments that follow.

Your contact with one of the rare Hippolais is likely to start with a glimpse of a rather heavy or ‘different’ movement in leaf canopy from an amorphous warbler. ‘Bit odd', you'll think and with your glasses on it, it will become odder. No strong olive or yellow anywhere, dull face, short wings and rather strong legs. It lacks the nimbleness of a Phylloscopus but clearly it is not a regular British Acrocephalus. The bird calls – a short, sharp ‘chick’ and rather slowly flicks its tail. Are you being duped by a Garden Warbler? No, the bird's bill is definitely not stubby and its face is more marked than you thought initially. Then you notice that the bird has short undertail coverts, these (or lack of these) contributing to a rather pear-shaped body. Now that points straight at a Hippolais and, considering the short wings and dull plumage, a rare one!

It's time to try harder and see particularly the bill and head more clearly. In addition, you must check its size. Happily, a Willow Warbler enters the bird's feeding patch and allows size comparison. What happens is hopefully either: The bird is noticeably bigger and heavier and displays a yellow- based ‘broom-handle’ of a bill, making it probably an Olivaceous, or: the bird is similarly sized and shows no great difference in its bill but has dark smudges over and below its dull supercilium, making it quite possibly a Booted.

Now, you must avoid adrenalin surge and yells of triumph at all costs. You have still not completely eliminated Blyth's Reed (which some think closely related to Hippolais and a dilute Melodious from Olivaceous and worn Chiffchaff or Bonelli's (the latter one of my downfalls) from Booted.

So there is only one sensible course of action; write your notes and then find help. It's far better to share a certain claim than suffer a reverse or a lifetime of hopeless wonder.

Your contact with one of the Oenanthe will be a striking rump patch of white that winks at you, as the bird flies off. The ‘flying off’ is the immediate problem for nearly all Wheatears are shy and used to escaping disturbance by lengthy flights, but you could get lucky. The birds pitches on a post and wags its tail at you. ‘Bit odd’ , you'll think, ‘the inverted T mark on the tail looks different and where the devil is its supercilium?’ What happens next is hopefully either:

The bird is all shades of sandy and dull brown, with even a trace of pink, and amazingly its tail is all black. Could be its one of the eastern Stonechats? No, the basic plumage pattern of the upperparts is not ‘mottled lines’ although it is rather small, compared to a (Northern) Wheatear nearby, it is clearly a wheatear sp.

So another size comparison to make sure that it is not actually bigger than the Wheatear and thus possibly an Isabelline and you can have definitive thoughts of a Desert. As a species, it is the least difficult that we are discussing, but if you are going to split it into a race, your problems have only just begun. You will need precise plumage colours, degree of white on the inner webs of the flight feathers and other minute characters. A case for a licensed ringer, I fear!

Or (1):

The bird is rather slim and delicate, looking rather long-tailed (or is it short legged?) and, yes, its face pattern is subdued, lacking the full supercilium blaze of the nearby Northern. It flits (rather lightly) on to the next post, flashing rump and tan again. The inverted T mark is not as strong as the Northern's. ‘What have I got here?’ you think. In western Europe, the historical status of wheatears offers you an awkward choice – Black-eared or Pied (or worse still a bit of both in a hybrid)? The bird dives off its second perch and shows you black underwing coverts.

Now, it's certain; you do have a rare wheatear to identify. The wing lining of Northern is no more than mottled black on a faintly dusky ground. You look again at the tail but actually that act will not finalise your search, because in both Black-eared and Pied the shape of the inverted T is variable and the diagnostic length of the black edge to the outer tail feathers is very, very difficult to see in the field.

So it's back to head and body plumage. You will need to note these fully if you are to make progress. What happens next is hopefully either(2):

You confirm that the head is only indistinctly marked – just a hint of a dusky lore, a pale smudge over the eve but a clean throat and that the back is virtually uniform in tone, like Northern. This combination points you at Black-eared, whether the basic ground colour is sandy or clay-brown (respectively suggesting a western or an eastern bird).

Or(2):

You note the foreparts and back of your bird are basically swarthy or earthy brown, with many faint pale feather fringes giving a mottled or scalloped appearance at close range. Its supercilium is a sort of splash behind the eye and its dusky chest spreads into rather sullied, un-clean underparts. In addition, its wing feathers are not noticeably chestnut on the greater coverts, tertial fringes and folded secondaries, quite unlike the nearby Northern (or Black-eared). This balance of characters points strongly at Pied.

Once again, it's ‘get it all written down’ followed smartly by calling up assistance.

In the above scenes, the avian characters have been taken to be in the plumages that they usually wear on their first migrations. These are shown in the accompanying plate, together with the underwing and tail patterns of the Wheatears, but there are of course other plumages to be considered, with those of adult male Wheatear the most different (but you can trust your field guide on those). To end this article, let me again stress how far-flung are the origins of the quintet.

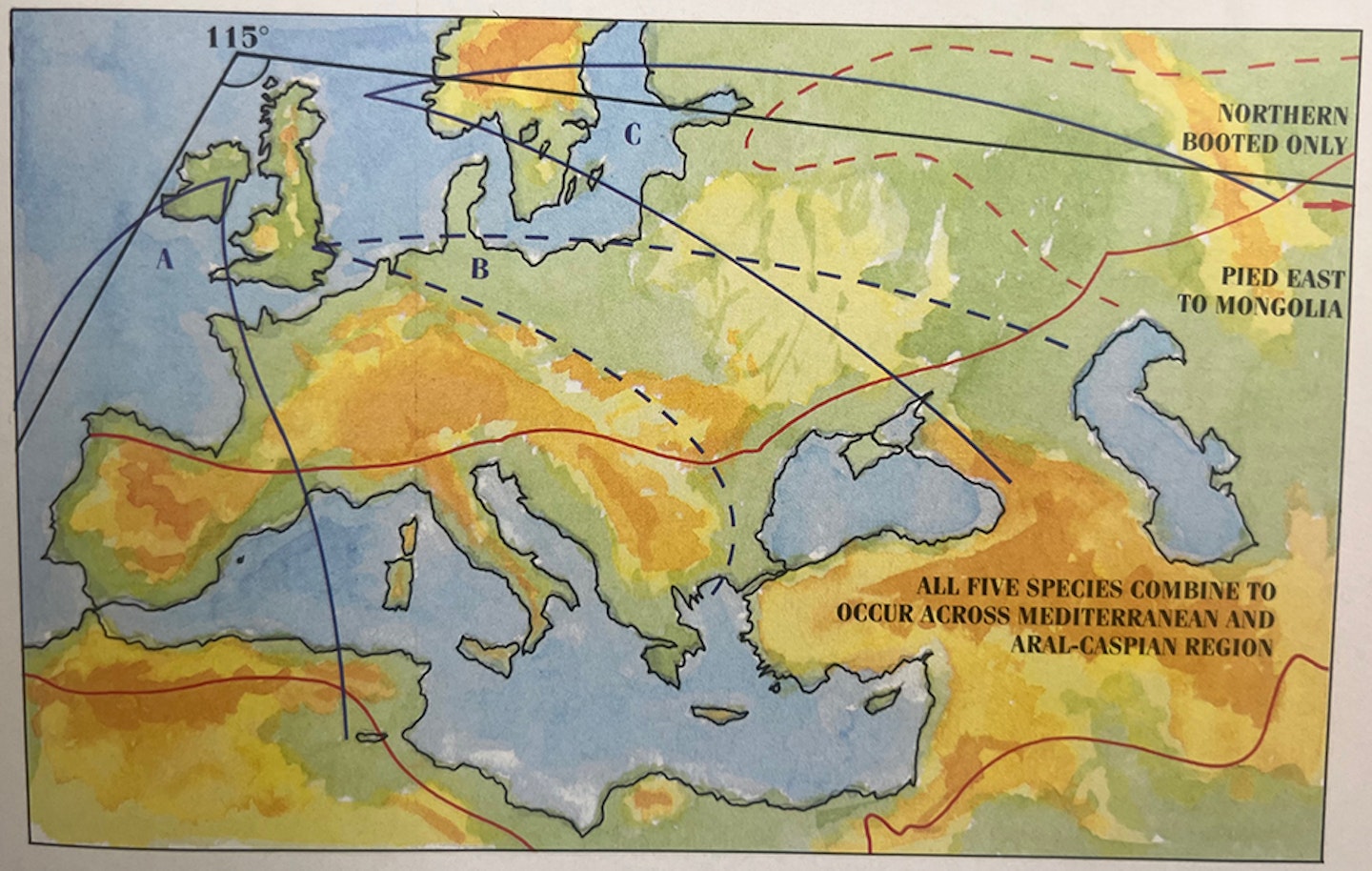

Map 1 shows their breeding ranges in the west Palearctic and the few vectors that are educable from the European records. Certainly some Booteds and the odd Olivaceous appear to come west across northern Europe; other Olivaceous ‘reverse’ their withdrawal from Iberia. It is the scatter of the three wheatears that really bewilders, with Pieds coming from no nearer than south west Asia. Black-eareds from both ends of their specific range and Deserts from at least three sectors of their distribution.

Above: The complex origins of Olivaceous and Booted Warblers and Desert, Black-eared and Pied Wheatears. In black, the 115° fan of known origins, in red, the outer limits of their combined breeding ranges; in blue, three approach vectors –

A ‘overshoots ,’' and ‘reserves’ from due S.

B (unproven) across lowlands of northern Europe and C 'piggy-backs ' on the classic autumn track of drift migrants and rarities.

2020s update

As stated in the text above, there have been considerably more UK records of all these species in recent decades.

Olivaceous and Booted Warblers are generally placed in the genus Iduna, rather than Hipploais, in the modern era of taxonomy.