A day on the marshes…

June 1988

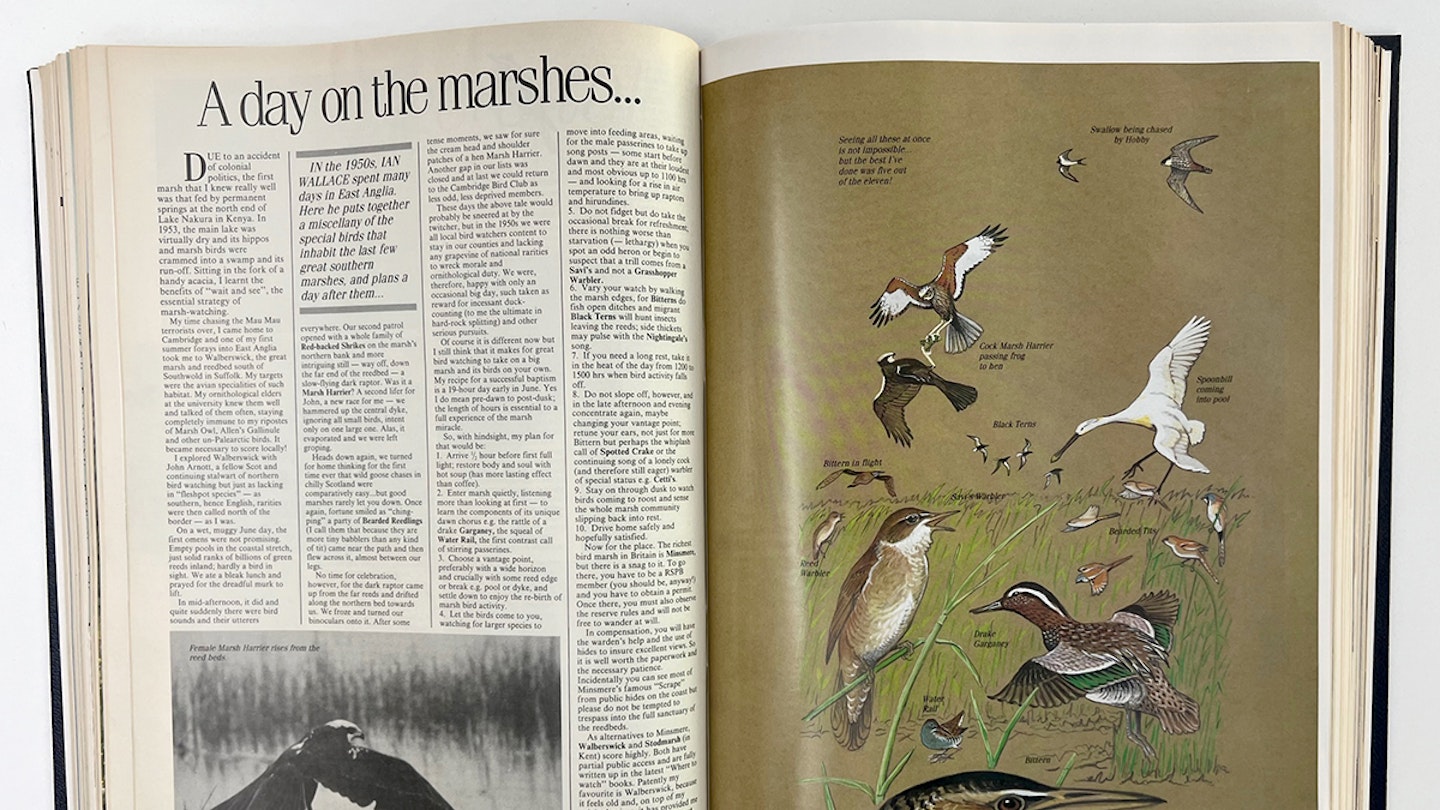

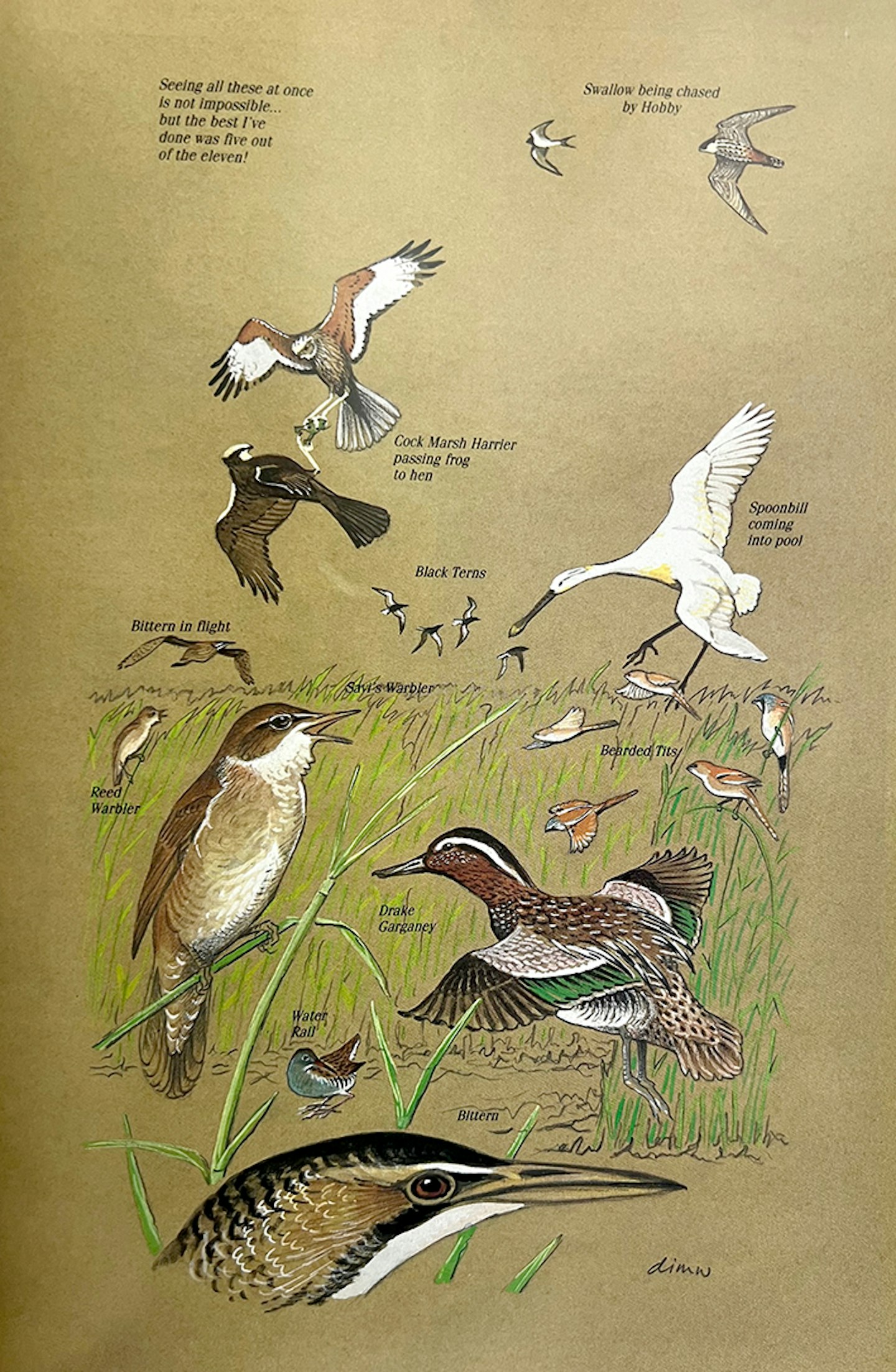

In the 1950s, Ian Wallace spent many days in East Anglia. Here he puts together a miscellany of the special birds that inhabit the last few great southern marshes, and plans a day after them..

Due to an accident politics, the first marsh that I knew really well was that fed by permanent springs at the north end of Lake Nakura, in Kenya. In 1953, the main lake was virtually dry and its Hippos and marsh birds were crammed into a swamp and its run-off. Sitting in the fork of a handy acacia, I learnt the benefits of ‘wait and see’, the essential strategy of marsh-watching.

My time chasing the Mau Mau terrorists over, I came home to Cambridge and one of my first summer forays into East Anglia took me to Walberswick, the great marsh and reedbed south of Southwold in Suffolk. My targets were the avian specialities of such habitat. My ornithological elders at the university knew them well and talked of them often, staying completely immune to my ripostes of Marsh Owl, Allen's Gallinule and other un-Palearctic birds. It became necessary to score, locally!

I explored Walberswick with John Arnott, a fellow Scot and continuing stalwart of northern birdwatching but just as lacking in ‘fleshpot species’ – as southern, hence English, rarities were then called north of the border – as I was.

On a wet, muggy June day, the first omens were not promising. Empty pools in the coastal stretch, just solid ranks of billions of green reeds inland; hardly a bird in sight. We ate a bleak lunch and prayed for the dreadful murk to lift.

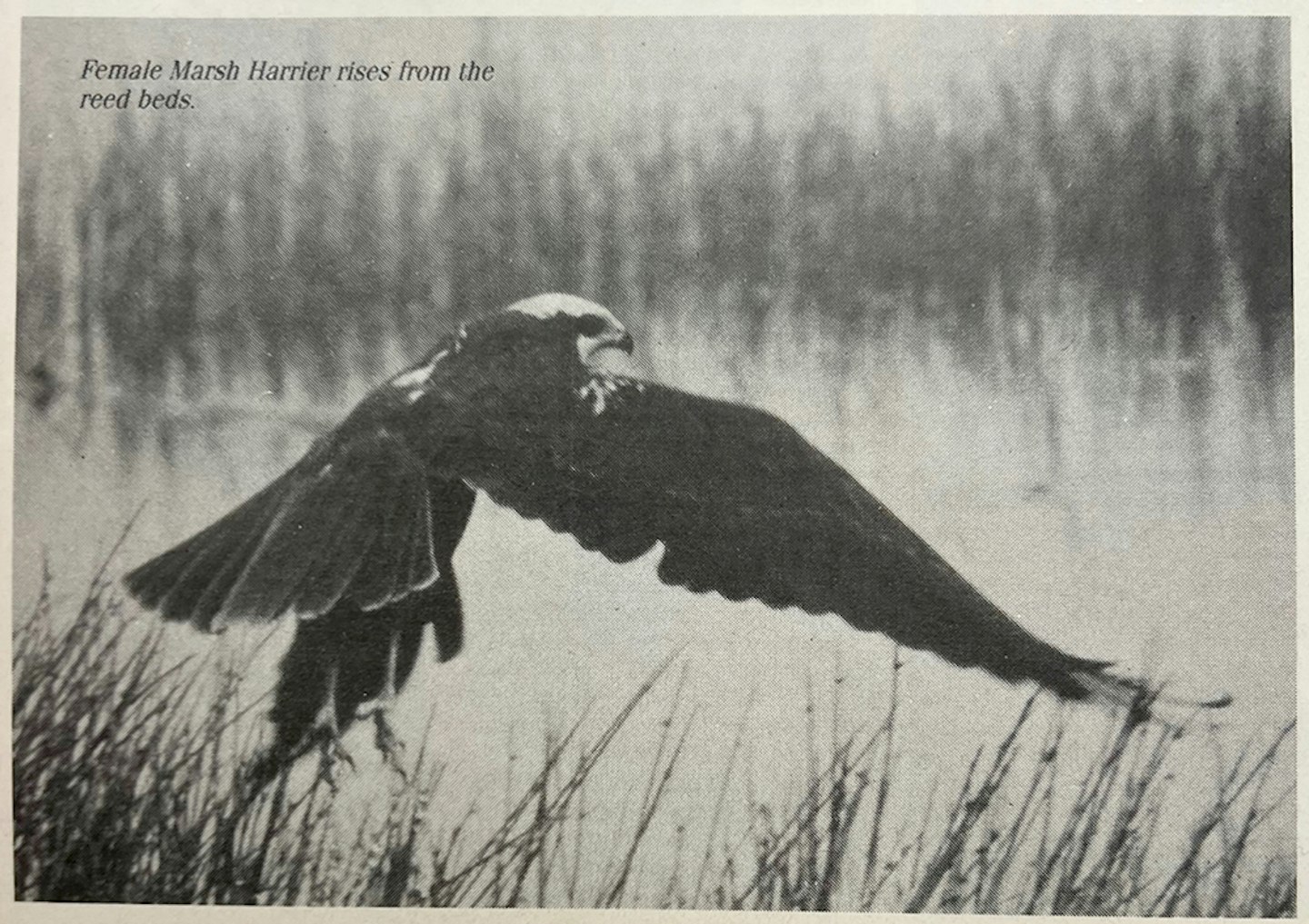

In mid-afternoon, it did and quite suddenly there were bird sounds and their utterers everywhere. Our second patrol opened with a whole family of Red-backed Shrikes on the marsh's northern bank and more intriguing still way off, down the far end of the reedbed a slow-flying dark raptor. Was it a Marsh Harrier? A second lifer for John, a new race for me; we hammered up the central dyke, ignoring all small birds, intent only on one large one. Alas, it evaporated and we were left groping.

Heads down again, we turned for home thinking for the first time ever that wild goose chases in chilly Scotland were comparatively easy, but good marshes rarely let you down. Once again, fortune smiled, as ’ching- ping’ a party of Bearded Reedlings (I call them that because they are more tiny babblers than any kind of tit) came near the path and then flew across it, almost between our legs.

No time for celebration, however, for the dark raptor came up from the far reeds and drifted along the northern bed towards us. We froze and turned our binoculars onto it. After some tense moments, we saw for sure the cream head and shoulder patches of a hen Marsh Harrier. Another gap in our lists was closed and at last we could return to the Cambridge Bird Club as less odd, less deprived members.

These days, the above tale would probably be sneered at by the twitcher, but in the 1950s, we were all local birdwatchers content to stay in our counties and lacking any grapevine of national rarities to wreck morale and ornithological duty. We were, therefore, happy with only an occasional big day, such taken as reward for incessant duck-counting (to me, the ultimate in hard-rock splitting) and other serious pursuits.

Of course it is different now, but I still think that it makes for great birdwatching to take on a big marsh and its birds on your own.

My recipe for a successful baptism is a 19-hour day early in June. Yes I do mean pre-dawn to post-dusk; the length of hours is essential to a full experience of the marsh miracle. So, with hindsight, my plan for that would be:

1. Arrive half an hour before first full light; restore body and soul with hot soup (has more lasting effect than coffee).

2. Enter marsh quietly, listening more than looking at first to learn the components of its unique dawn chorus e.g. the rattle of a drake Garganey, the squeal of Water Rail, the first contrast call of stirring passerines.

3. Choose a vantage point, preferably with a wide horizon and crucially with some reed edge or break e.g. pool or dyke, and settle down to enjoy the re-birth of marsh bird activity.

4. Let the birds come to you, watching for larger species to move into feeding areas, waiting for the male passerines to take up song posts – some start before dawn and they are at their loudest and most obvious up to 1100 hrs and looking for a rise in air temperature to bring up raptors and hirundines.

5. Do not fidget, but do take the occasional break for refreshment; there is nothing worse than starvation (lethargy) when you spot an odd heron or begin to suspect that a trill comes from a Savi's and not a Grasshopper Warbler.

6. Vary your watch by walking the marsh edges, for Bitterns do fish open ditches and migrant Black Terns will hunt insects leaving the reeds; side thickets may pulse with the Nightingale's song.

7. If you need a long rest, take it in the heat of the day from 1200 to 1500 hrs when bird activity falls off.

8. Do not slope off, however, and in the late afternoon and evening concentrate again, maybe changing your vantage point; retune your ears, not just for more Bittern but perhaps the whiplash call of Spotted Crake or the continuing song of a lonely cock (and therefore still eager) warbler of special status e.g. Cetti's.

9. Stay on through dusk to watch birds coming to roost and sense the whole marsh community slipping back into rest.

10. Drive home safely and hopefully satisfied.

Now for the place. The richest bird marsh in Britain is Minsmere, but there is a snag to it. To go there, you have to be a RSPB member (you should be, anyway!) and you have to obtain a permit. Once there, you must also observe the reserve rules and will not be free to wander at will.

In compensation, you will have the warden's help and the use of hides to insure excellent views. So it is well worth the paperwork and the necessary patience.

Incidentally, you can see most of Minsmere's famous ‘Scrape’ from public hides on the coast but please do not be tempted to trespass into the full sanctuary of the reedbeds.

As alternatives to Minsmere, Walberswick and Stodmarsh (in Kent) score highly. Both have partial public access and are fully written up in the latest ‘Where to watch’ books. Patently my favourite is Walberswick, because it feels old and, on top of my original prizes, it has provided me with passage gems like Firecrest, ‘northern’ Willow Tit and Water Pipit, but Stodmarsh can be excellent, with semi-resident Glossy Ibis [no longer present, but they are much more common around the country, these days] thrown in for good measure.

Understand, however, that the real joy of a big marsh visit is not the odd rare bird. It is the experience of an unusual wetland community, as depicted in my plate. Good luck and no rain on your long June day!