Great White Birds

March 1988

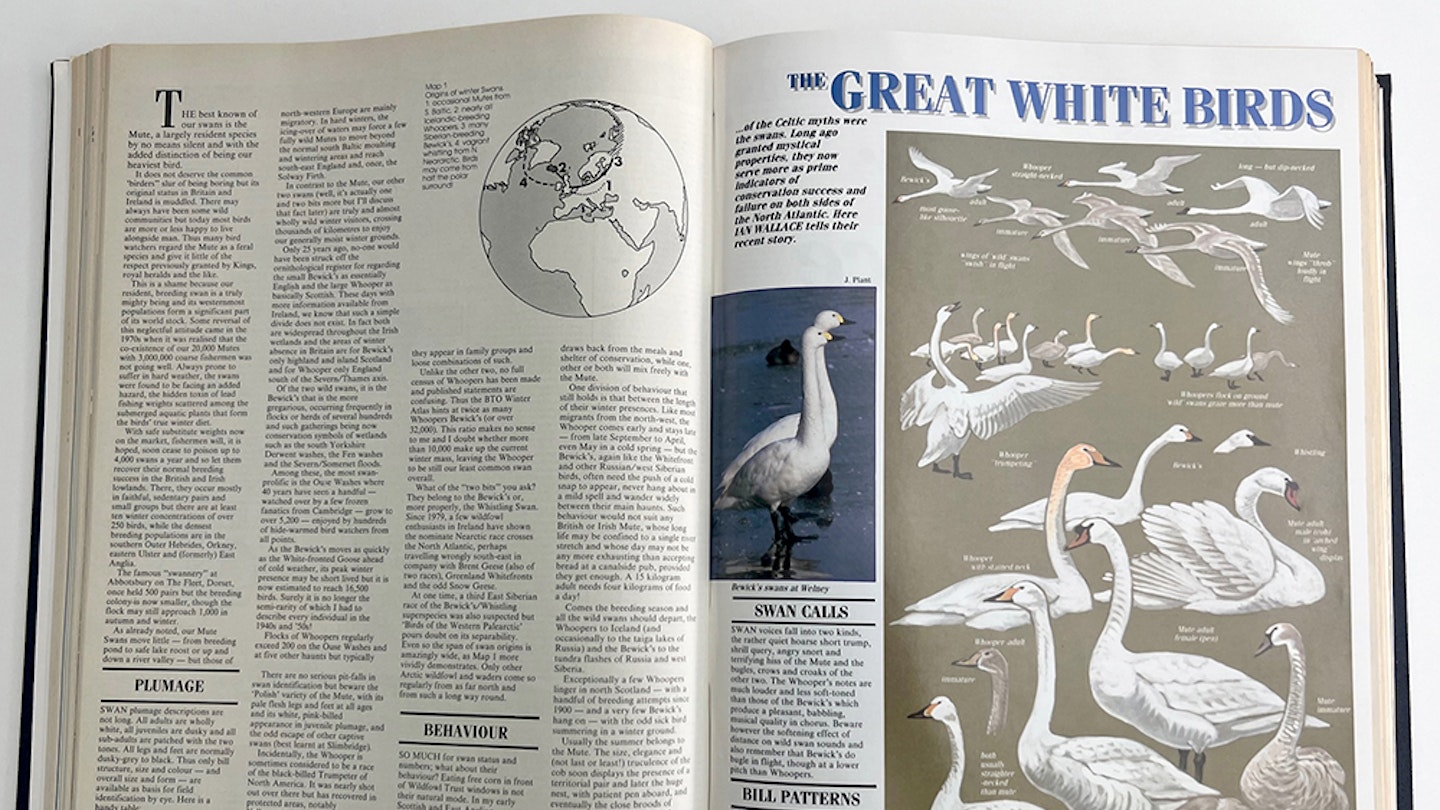

The great white birds of the Celtic myths were the swans. Long ago granted mystical properties, they now serve more as prime indicators of conservation success and failure on both sides of the North Atlantic. Here Ian Wallace tells their recent story.

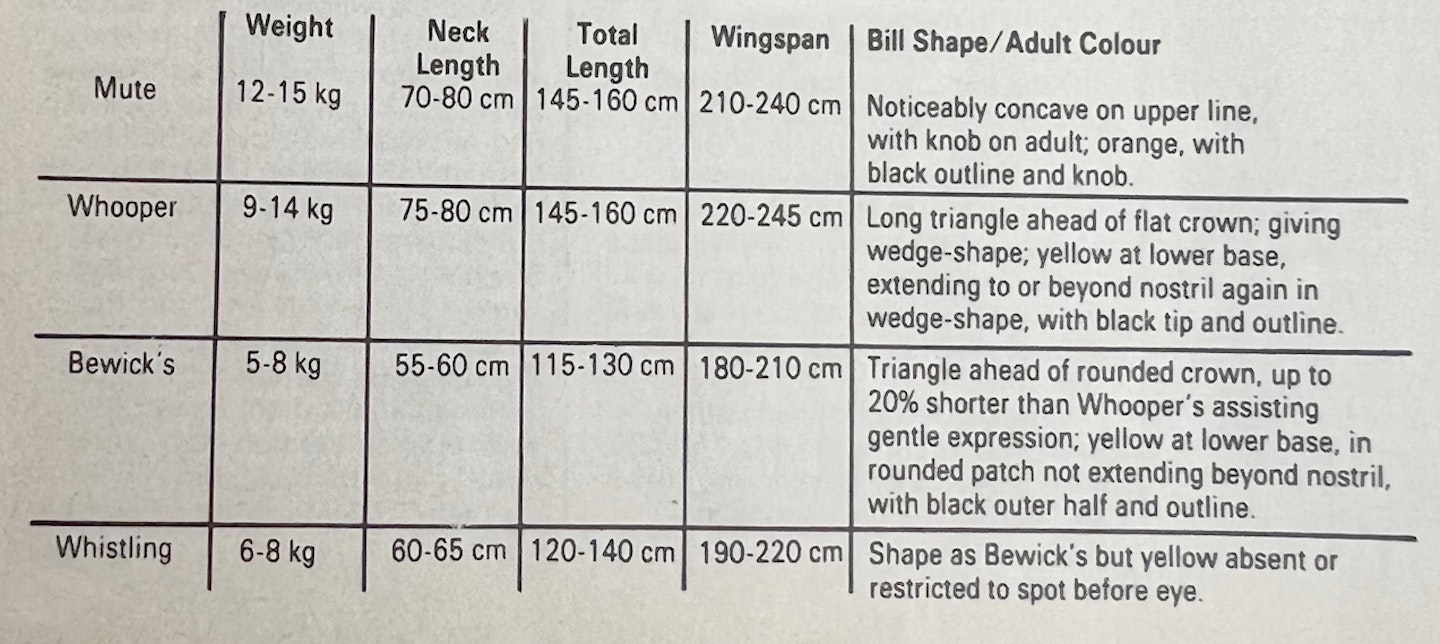

The best known of our swans is the Mute, a largely resident species by no means silent and with the added distinction of being our heaviest bird.

It does not deserve the common birders’ slur of being boring but its original status in Britain and Ireland is muddled. There may always have been some wild communities, but today most birds are more or less happy to live alongside man. Thus, many birdwatchers regard the Mute as a feral species and give it little of the respect previously granted by kings, royal heralds and the like.

This is a shame, because our resident, breeding swan is a truly mighty being and its westernmost populations form a significant part of its world stock. Some reversal of this neglectful attitude came in the 1970s when it was realised that the co-existence of our 20.000 Mutes with 3,000,000 coarse fishermen was not going well. Always prone to suffer in hard weather, the swans were found to be facing an added hazard, the hidden toxin of lead fishing weights scattered among the submerged aquatic plants that form the birds' true winter diet.

With safe substitute weights now on the market, fishermen will, it is hoped, soon cease to poison up to 4,000 swans a year and so let them recover their normal breeding success in the British and Irish lowlands. There, they occur mostly in faithful, sedentary pairs and small groups but there are at least ten winter concentrations of over 250 birds, while the densest breeding populations are in the southern Outer Hebrides, Orkney, eastern Ulster and (formerly) East Anglia.

The famous ‘swannery’ at Abbotsbury on The Fleet, Dorset, once held 500 pairs but the breeding colony is now smaller, though the flock may still approach 1,000 in autumn and winter.

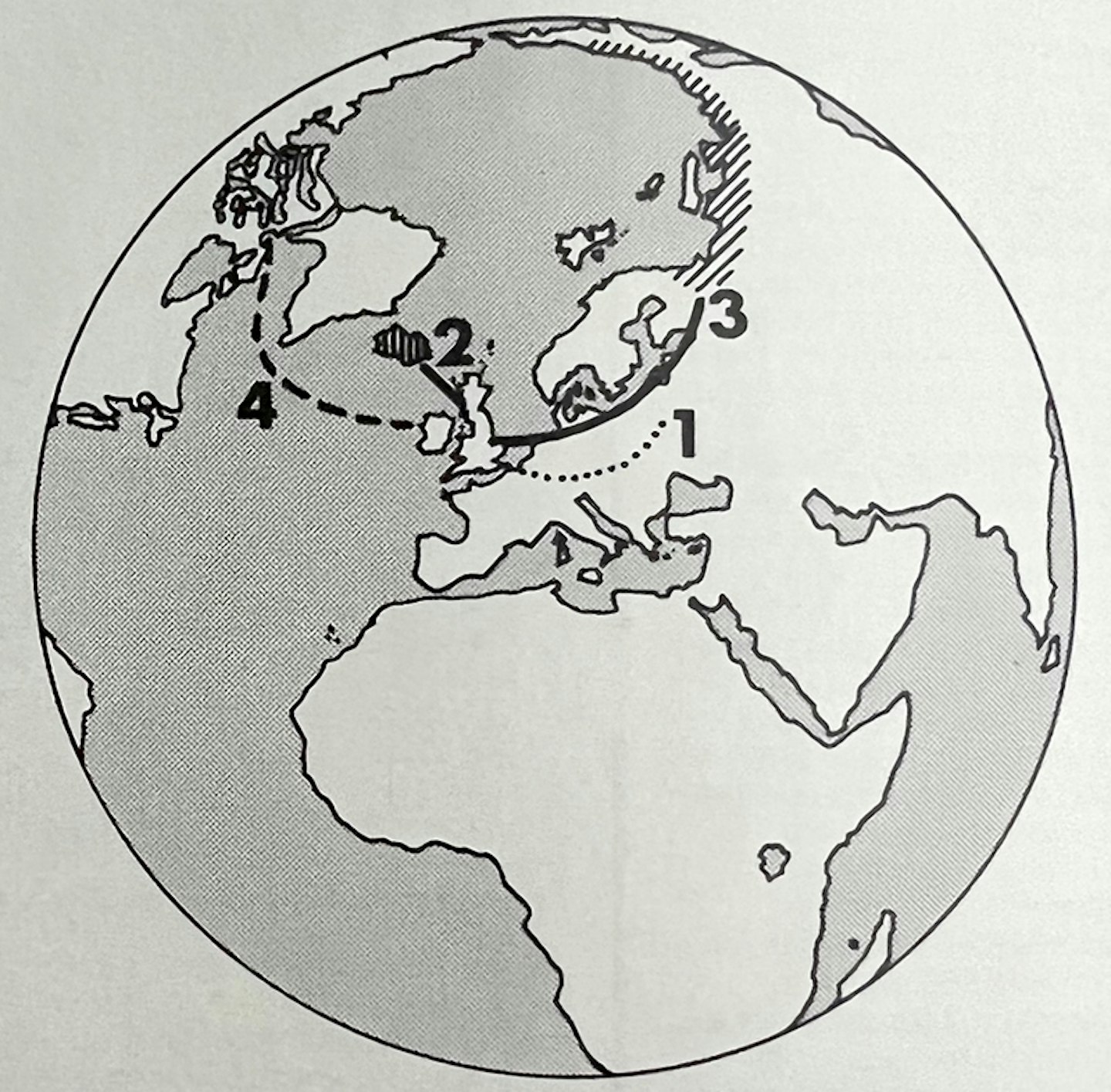

As already noted, our Mute Swans move little – from breeding pond to safe lake roost or up and down a river valley – but those of north-western Europe are mainly migratory. In hard winters, the icing-over of waters may force a few fully wild Mutes to move beyond the normal south Baltic moulting and wintering areas and reach south-east England and, once, the Solway Firth.

Wild swans

In contrast to the Mute, our other two swans (well, it's actually one and two bits more but I'll discuss that fact later) are truly and almost wholly wild winter visitors, crossing thousands of kilometres to enjoy our generally moist winter grounds.

Only 25 years ago, no-one would have been struck off the ornithological register for regarding the small Bewick's as essentially English and the large Whooper as basically Scottish. These days with more information available from Ireland, we know that such a simple divide does not exist. In fact both are widespread throughout the Irish wetlands and the areas of winter absence in Britain are for Bewick's only highland and island Scotland and for Whooper only England south of the Severn/Thames axis.

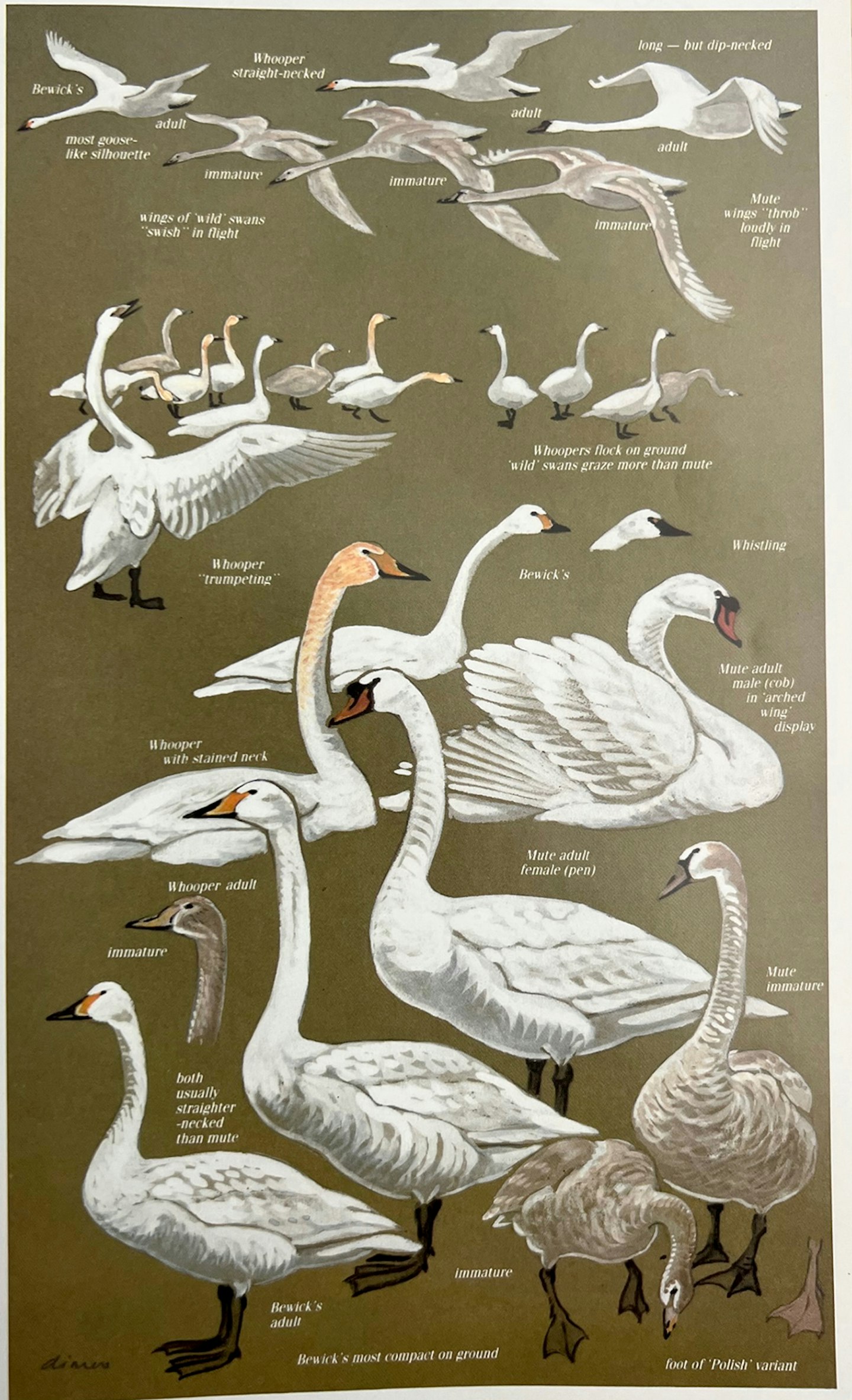

Of the two wild swans, it is the Bewick's that is the more gregarious, occurring frequently in flocks or herds of several hundreds and such gatherings being now conservation symbols of wetlands such as the south Yorkshire Derwent washes, the Fen washes and the Severn/Somerset floods. Among these, the most swan- prolific is the Oure Washes where 40 years have seen a handful – watched over by a few frozen fanatics from Cambridge – grow to over 5,200 – enjoyed by hundreds of hide-warmed birdwatchers from all points.

As the Bewick's moves as quickly as the White-fronted Goose ahead of cold weather, its peak winter presence may be short lived but it is now estimated to reach 16.500 birds. Surely it is no longer the semi-rarity of which I had to describe every individual in the 1940s and '50s!

Flocks of Whoopers regularly exceed 200 on the Ouse Washes and at five other haunts but typically, they appear in family groups and loose combinations of such.

Unlike the other two, no full census of Whoopers has been made and published statements are confusing. Thus the BTO Winter Atlas hints at twice as many Whoopers Bewick's (or over 32,000). This ratio makes no sense to me and I doubt whether more than 10,000 make up the current winter mass, leaving the Whooper to be still our least common swan overall.

What of the ‘two bits’ you ask? They belong to the Bewick's or, more properly, the Whistling Swan. Since 1979, a few wildfowl enthusiasts in Ireland have shown the nominate Nearctic race crosses the North Atlantic, perhaps travelling wrongly south-east in company with Brent Geese (also of two races), Greenland Whitefronts and the odd Snow Geese.

At one time, a third East Siberian race of the Bewick's/Whistling superspecies was also suspected but Birds of the Western Palearctic (BWP) pours doubt on its separability. Even so the span of swan origins is amazingly wide, as Map 1 more vividly demonstrates. Only other Arctic wildfowl and waders come so regularly from as far north and from such a long way round.

Behaviour

So much for swan status and numbers; what about their behaviour? Eating free corn in front of Wildfowl Trust windows is not their natural mode. In my early Scottish and East Anglian experience, the two wild birds spent their winter days quite differently the Bewick's predominantly at home on flooded grass sumps, nibbling away with almost goose- like precision, and the Whooper far less addicted to any one niche, as often gleaning weedy farmland or up-ending in small waters as lumbering over marshes.

In recent years, however, the division of habit has loosened (at least in England) and now neither draws back from the meals and shelter of conservation, while one, the other or both will mix freely with the Mute.

One division of behaviour that still holds is that between the length of their winter presences. Like most migrants from the north-west, the Whooper comes early and stays late – from late September to April even May in a cold spring – but the Bewick's, again like the Whitefront and other Russian/ west Siberian birds, often need the push of a cold snap to appear, never hang about in a mild spell and wander widely between their main haunts. Such behaviour would not suit any British or Irish Mute, whose long life may be confined to a single river stretch and whose day may not be any more exhausting than accepting bread at a canalside pub, provided they get enough. A 15 kilogram adult needs four kilograms of food a day!

Come the breeding season all the wild swans should depart, the Whoopers to Iceland (and occasionally to the taiga lakes of Russia) and the Bewick's to the tundra flashes of Russia and west Siberia.

Exceptionally, a few Whoopers linger in north Scotland – with a handful of breeding attempts since 1900 – and a very few Bewick's hang on – with the odd sick bird summering in a winter ground. Usually the summer belongs to the Mute. The size, elegance and (not last or least!) truculence of the cob soon displays the presence of a territorial pair and later the huge nest, with patient pen aboard, and eventually the close broods of charming cygnets afford much pleasure to many more people than birdwatchers.

The normal clutch is five to six eggs. In the recent years of lead poisoning, many layings have failed certainly the two pairs that I watch have hatched no egg in five attempts – and cygnet starvation, caused by adults using waters to0 small to provide a full natural diet, is also frequent. The Mute may not be in serious trouble but it needs every help still.

Swan calls

Swan voices fall into two kinds, the rather quiet hoarse short trump, shilling is a he The north a and the bugles, crows and croaks of the other two. The Whooper's notes are much louder and less soft-toned than those of the Bewick's which produce a pleasant, babbling, musical quality in chorus. Beware however the softening effect of distance on wild swan sounds and also remember that Bewick's do bugle in flight, though at a lower pitch than Whoopers.

Bill patterns

One particular fascination of the Bewick's needs a mention and that is the individual, apparently infinite variation of the adult bill patterns. This has allowed Sir Peter Scott and his family to name hundreds of swans and so greet them from Winter to winter. It's well worth the lime to learn more of their fidelity to mate and place when you visit Slimbridge, the university of swan students. There is no better place to see the great white birds.

Plumage

There are no serious pit-falls in swan identification but beware the ‘Polish' variety of the Mute, with its pale flesh legs and feet at all ages and its white, pink-billed appearance in juvenile plumage, and the odd escape of other captive swans (best learnt at Slimbridge). Incidentally, the Whooper is sometimes considered to be a race of the black-billed Trumpeter of North America. It was nearly shot out over there but has recovered in protected areas, notably Yellowstone.

Swan plumage descriptions are not long. All adults are wholly white, all juveniles are dusky and all sub-adults are patched with the two tones. All legs and feet are normally dusky-grey to black. Thus only bill structure, size and colour – and overall size and form – are available as basis for field identification by eye. Here is a handy table:

2020s update

These days, thousands of Whooper Swans winter in East Anglia around the Ouse Washes and Nene Washes. The latest estimate of Whooper Swan wintering UK population is 11,000 birds.

Up to 5,000 Bewick’s Swans winter in the UK, though they appear to be declining in the UK as wintering birds.