North Sea travellers

November 1987

Although not regarded as one of the more romantic passerine tribes, the winter thrushes present a real challenge to the hunting bird watcher. Close study of the common species should produce a rare fellow-traveller, argues Ian Wallace, who tells you how to search for them.

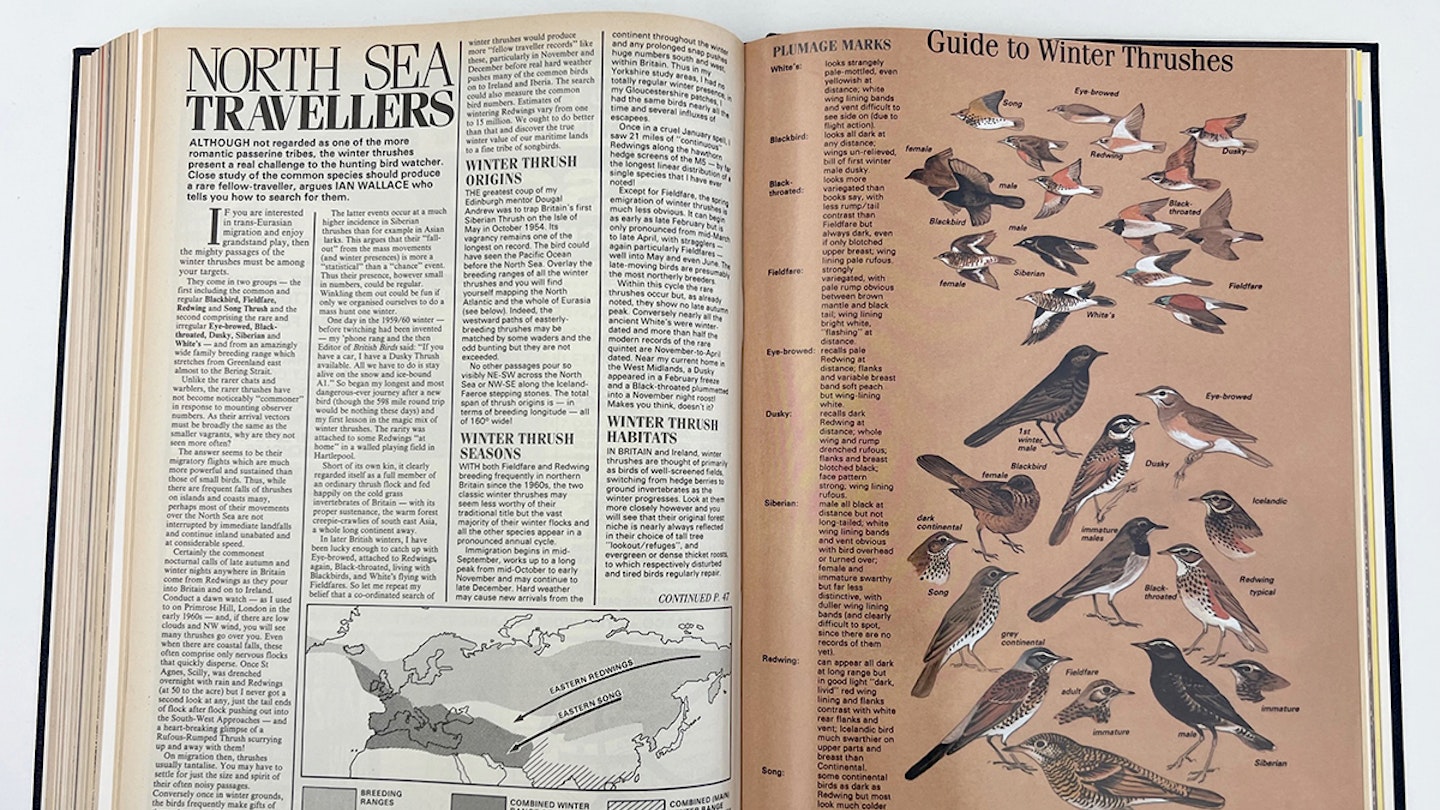

Guide to Winter Thrushes

White’s Thrush looks strangely pale-mottled, even yellowish at distance; white wing lining bands and vent difficult to see side on (due to flight action).

Blackbird looks all dark at any distance; wings un-relieved, bill of first winter male dusky.

Black-throated Thrush looks more variegated than books say, with less rump/tail contrast than Fieldfare but always dark, even if only blotched upper breast; wing lining pale rufous.

Fieldfare strongly variegated, with pale rump obvious between brown mantle and black tail; wing lining bright white, "flashing at distance.

Eye-browed Thrush recalls pale Redwing at distance: flanks and variable breast band soft peach but wing-lining white.

Dusky Thrush recalls dark Redwing at distance; whole wing and rump drenched rufous; flanks and breast blotched black: face pattern strong; wing lining rufous.

Siberian Thrush male all black at distance but not long-tailed; white wing lining bands and vent obvious with bird overhead or turned over: female and immature swarthy but far less distinctive, with duller wing lining bands (and clearly difficult to spot, since there are no records of them vet).

Redwing can appear all dark at long range but in good light "dark. livid" red wing lining and flanks contrast with white rear flanks and vent: Icelandic bird much swarthier on upper parts and breast than Continental.

Song Thrush some continental birds as dark as Redwing but most look much colder and cleaner than British stock; in good light, "'Cool" butt wing lining shows but spots obscure pale vent.

If you are interested in trans-Eurasian migration and enjoy grandstand play, then the mighty passages of the winter thrushes must be among your targets.

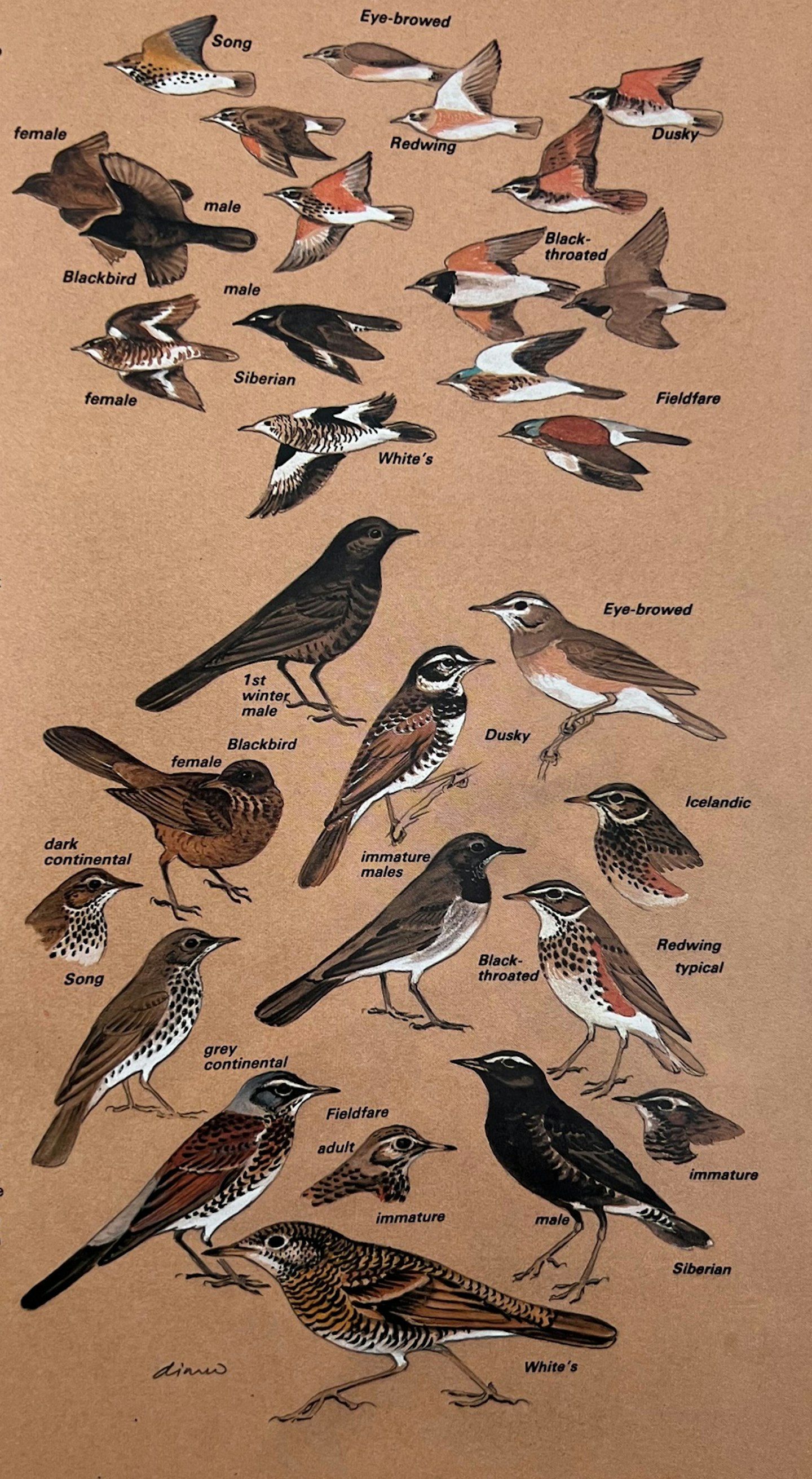

They come in two groups – the first including the common and regular Blackbird, Fieldfare, Redwing and Song Thrush and the second comprising the rare and irregular Eye-browed, Black-throated, Dusky, Siberian and White's – and from an amazingly wide family breeding range which stretches from Greenland east almost to the Bering Strait.

Unlike the rarer chats and warblers, the rarer thrushes have not become noticeably "commoner"' in response to mounting observer numbers. As their arrival vectors must be broadly the same as the smaller vagrants, why are they not seen more often?

The answer seems to be their migratory flights which are much more powerful and sustained than those of small birds. Thus, while there are frequent falls of thrushes on islands and coasts many, perhaps most of their movements over the North Sea are not interrupted by immediate landfalls and continue inland unabated and at considerable speed.

Certainly, the commonest nocturnal calls of late autumn and winter nights anywhere in Britain come from Redwings as they pour into Britain and on to Ireland. Conduct a dawn watch – as I used to on Primrose Hill, London in the early 1960s – and, if there are low clouds and NW wind, you will see many thrushes go over you. Even when there are coastal falls, these often comprise only nervous flocks that quickly disperse. Once St Agnes, Scilly, was drenched overnight with rain and Redwings (at 50 to the acre) but I never got a second look at any, just the tail ends of flock after flock pushing out into the South-West Approaches – and a heart-breaking glimpse of a Rufous-rumped Thrush scurrying up and away with them!

On migration then, thrushes usually tantalise. You may have to settle for just the size and spirit of their often noisy passages. Conversely once in winter grounds, the birds frequently make gifts of themselves – with the common species easily seen from car or even house window and the rarities liable to appear among them in widely scattered inland localities.

The latter events occur at a much higher incidence in Siberian thrushes than for example in Asian larks. This argues that their "fall- out" from the mass movements (and winter presences) is more a "statistical" than a "chance" event. Thus their presence, however small in numbers, could be regular. Winkling them out could be fun if only we organised ourselves to do a mass hunt one winter.

One day in the 1959/60 winter – before twitching had been invented – my phone rang and the then editor of British Birds said: "If you have a car, I have a Dusky Thrush available. All we have to do is stay alive on the snow and ice-bound A1." So began my longest and most dangerous-ever journey after a new bird (though the 598 mile round trip would be nothing these days) and my first lesson in the magic mix of winter thrushes. The rarity was attached to some Redwings "at home" in a walled playing field in Hartlepool.

Short of its own kin, it clearly regarded itself as a full member of an ordinary thrush flock and fed happily on the cold grass invertebrates of Britain – with its proper sustenance, the warm forest creepie-crawlies of south east Asia, a whole long continent away.

In later British winters, I have been lucky enough to catch up with Eye-browed, attached to Redwings, again, Black-throated, living with Blackbirds, and White's flying with Fieldfares. So let me repeat my belief that a co-ordinated search of winter thrushes would produce more "fellow traveller records"' like these, particularly in November and December before real hard weather pushes many of the common birds on to Ireland and Iberia. The search could also measure the common bird numbers. Estimates of wintering Redwings vary from one to 15 million. We ought to do better than that and discover the true winter value of our maritime lands to a fine tribe of songbirds.

Winter thrush origins

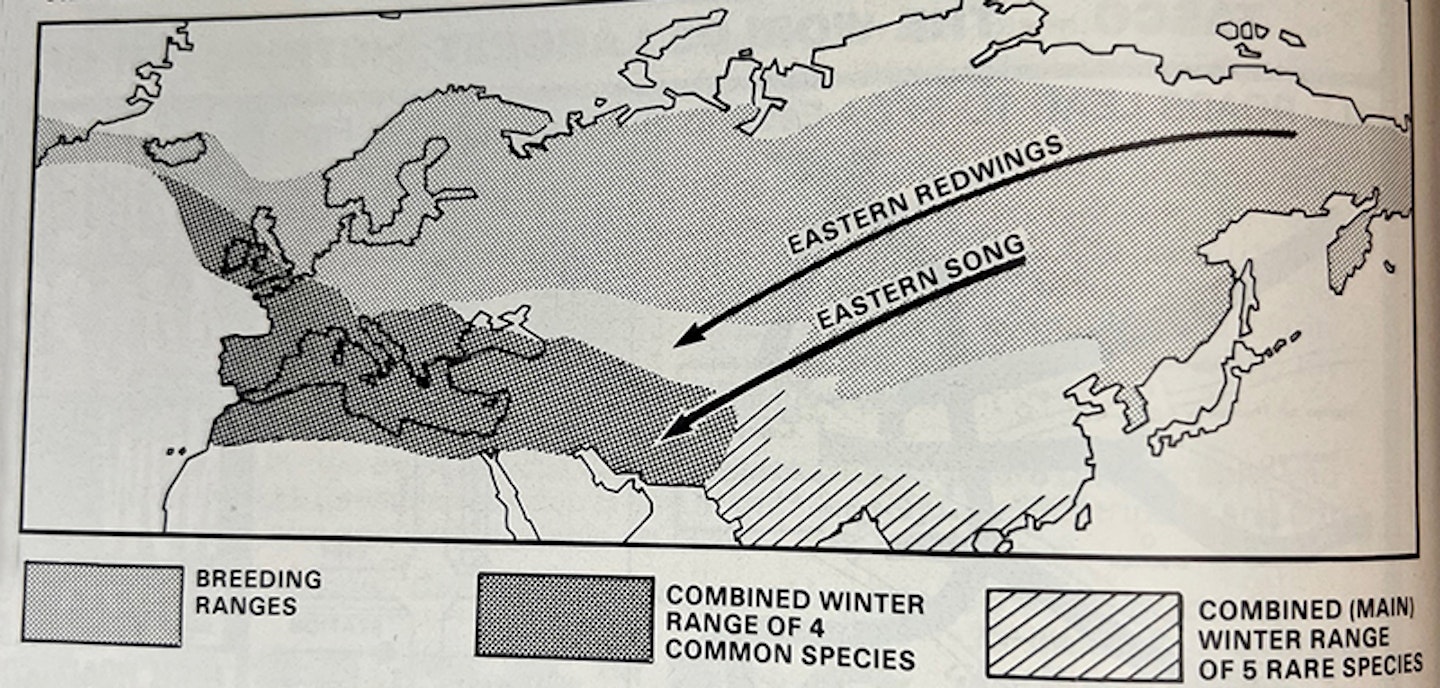

The greatest coup of my Edinburgh mentor Dougal Andrew was to trap Britain's first Siberian Thrush on the Isle of May in October 1954. Its vagrancy remains one of the longest on record. The bird could have seen the Pacific Ocean before the North Sea. Overlay the breeding ranges of all the winter thrushes and you will find yourself mapping the North Atlantic and the whole of Eurasia (see below). Indeed, the westward paths of easterly- breeding thrushes may be matched by some waders and the odd bunting but they are not exceeded.

No other passages pour so visibly NE-SW across the North Sea or NW-SE along the Iceland- Faeroe stepping stones. The total span of thrush origins is – in terms of breeding longitude – of 160° wide!

Winter thrush seasons

With both Fieldfare and Redwing breeding frequently in northern Britain since the 1960s, the two classic winter thrushes may seem less worthy of their traditional title but the vast majority of their winter flocks and all the other species appear in a pronounced annual cycle.

Immigration begins in mid- September, works up to a long peak from mid-October to early November and may continue to late December. Hard weather may cause new arrivals from the continent throughout the winter and any prolonged snap pushes huge numbers south and west, within Britain. Thus in my Yorkshire study areas, I had no totally regular winter presence; in my Gloucestershire patches, I had the same birds nearly all the time and several influxes of escapees.

Once in a cruel January spell, I saw 21 miles of “continuous” Redwings along the Hawthorn hedge screens of the M5 – by far the longest linear distribution of a single species that I have ever noted! Except for Fieldfare, the spring emigration of winter thrushes is much less obvious. It can begin as early as late February but is only pronounced from mid-March to late April, with stragglers again particularly Fieldfares well into May and even June. The late-moving birds are presumably the most northerly breeders. Within this cycle the rare thrushes occur but, as already noted, they show no late autumn peak. Conversely nearly all the ancient White's were winter- dated and more than half the modern records of the rare quintet are November-to-April dated. Near my current home in the West Midlands, a Dusky appeared in a February freeze and a Black-throated plummeted into a November night roost! Makes you think, doesn't it?

Winter thrush habitats

In Britain and Ireland, winter thrushes are thought of primarily as birds of well-screened fields, switching from hedge berries to ground invertebrates as the winter progresses. Look at them more closely however and you will see that their original forest niche is nearly always reflected In their choice of tall tree "lookout/refuges", and evergreen or dense thicket roosts, o which respectively disturbed and tired birds regularly repair. In escape the smaller species usually use the screen of whatever canopy exists but the brave Fieldfare sits characteristically on the topmost bare twigs. For regular close searching of vour local birds, find the areas in which you can watch birds from road or lane. A mix of damp fields, field hedges and small orchards is recommended In hard weather winter thrushes freely invade gardens and Redwings and Song Thrushes especially may need all the food and water that you can give them. The last are particularly vulnerable to excessive weight loss as they run before glaciation. They often die en masse if they cannot find open ground.

Flocking behaviour

Thrush flocks are largest and most cohesive on migration or in winter evacuations. Over 260 000 birds once fell into some Orkney fields but the typical winter flocks number only 200 300 in Fieldfare and Redwing and may be much smaller and looser knit in Blackbird and Song Thrush. The latter behaviour disguises presences and probably costs us records of the rarer species in quiet woods and hidden fields Certainly two of my oddities have come from isolated thickets that to my knowledge no other bird watchers had searched of all the tribe. White's is the most solitary and retiring, retreating into woods to feed on the leaf floor. No wonder the modern bird watcher finds fewer than the ancient bird hunters who had to work their countryside for the then compulsory (and valuable) skins.

General characters

The biggest winter thrush is White's. which remarkably has a hint of Green Woodpecker about its form and flight action (though It runs on the ground). Next in size come the robust Fieldfare and Black-throated, the former fling rather leisurely with a loose wing beat and the latter showing that action and a bit of the Blackbird's. Next comes the round headed. slim-vented and long-tailed Blackbird. which hurtles along with irregular wing strokes. Finally come the fairly stocky pair of Dusky and Siberian the latter with the hint of an Oriole in its flight action, and the slim trio of Song, Eye-browed and Redwing, the last two dashing along like Starlings and looking little bigger than them. It is well worth your time to fix the images of the common quartet firmly in your mind's eye and so be able to spot an odd man out.

Map breeding (upper) and wintering (lower) shows ranges of Britain's nine winter Thrushes. Note how former exceeds latter, even in case of Redwing and Song Thrush, and evokes chances of extreme vagrancy even in "Common" species!

NORTH SEA TRAVELLERS

In escape, the smaller species usually use the screen of whatever canopy exists but the brave Fieldfare sits characteristically on the topmost bare twigs. For regular close searching of your local birds, find the areas in which you can watch birds from road or lane. A mix of damp fields, field hedges and small orchards is recommended.

In hard weather, winter thrushes freely invade gardens and Redwings and Song Thrushes especially may need all the food and water that you can give them. The last are particularly vulnerable to excessive weight loss as they run before glaciation. They often die en masse if they cannot find open ground.

FLOCKING BEHAVIOUR

Thrush flocks are largest and most cohesive on migration or in winter evacuations. Over 250,000 birds once fell into some Orkney fields, but the typical winter flocks number only 200-300 in Fieldfare and Redwing and may be much smaller and looser-knit in Blackbird and Song Thrush. The latter behaviour

disguises presences and probably costs us records of the rarer species in quiet woods and hidden fields. Certainly two of my oddities have come from isolated thickets that to my knowledge no other birdwatchers had searched.

Of all the tribe, White's is the most solitary and retiring, retreating into woods to feed on the leaf floor. No wonder the modern birdwatcher finds fewer than the ancient bird hunters who had to work their countryside for the then compulsory (and valuable) skins.

GENERAL CHARACTERS

THE biggest winter thrush is White's, which remarkably has a hint of Green Woodpecker about its form and flight action (though it runs on the ground). Next in size come the robust Fieldfare and Black-throated, the former flying rather leisurely with a loose wing beat and the latter showing that action and a bit of the Blackbird's. Next comes the round-headed, slim-vented and long-tailed Blackbird, which hurtles along with irregular wing strokes. Finally come the fairly stocky pair of Dusky and Siberian, the latter with the hint of an Oriole in its flight action, and the slim trio of Song, Eye-browed and Redwing, the last two dashing along like Starlings and looking little bigger than them. It is well worth your time to fix the images of the common quartet firmly in your mind's eye and so be able to spot an odd man out.