Auks in Winter

December 1987

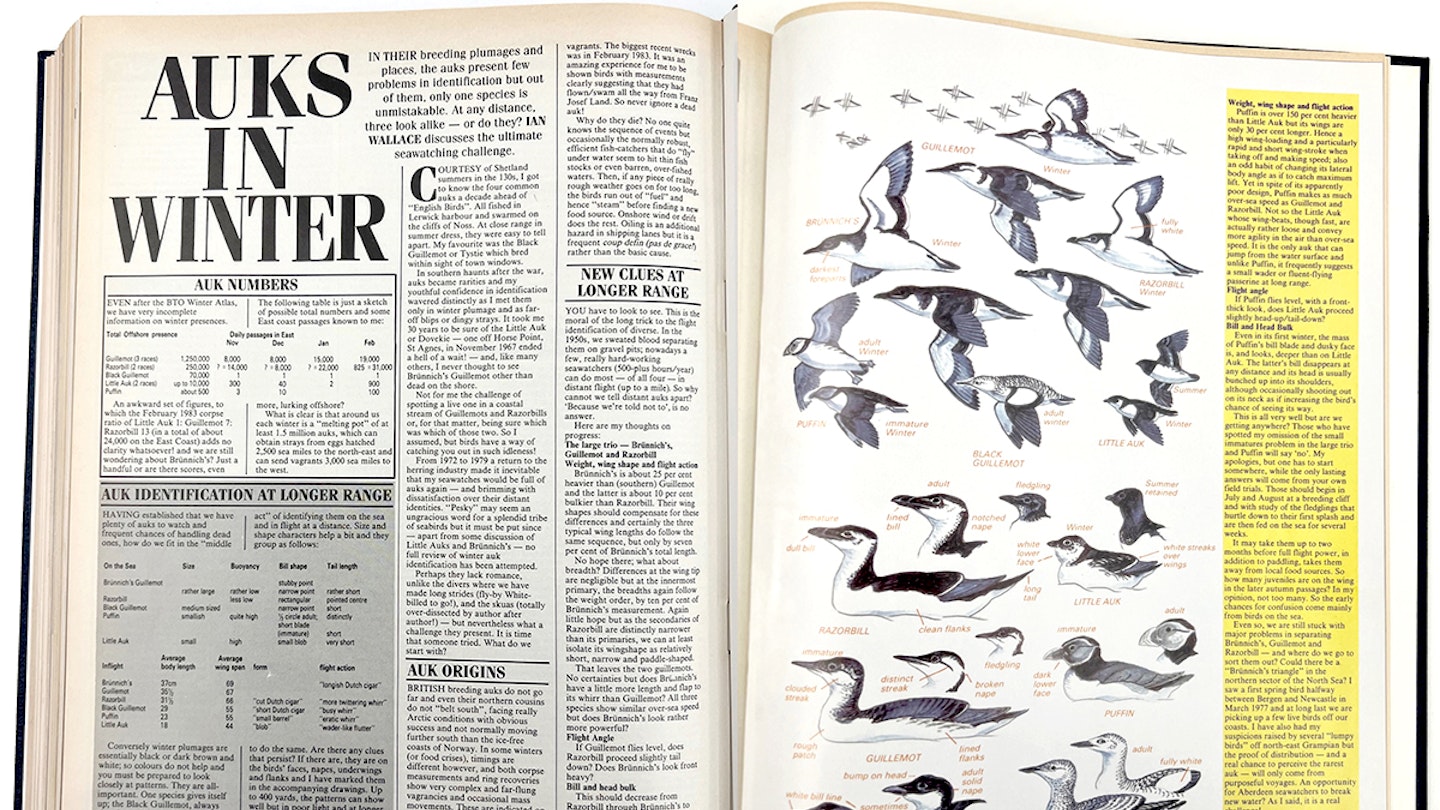

In their breeding plumages and places, the auks present few problems in identification but out of them, only one species is unmistakable. At any distance, three look alike or do they? Ian Wallace discusses the ultimate seawatching challenge.

Courtesy of Shetland summers in the 1930s, I got to know the four common auks a decade ahead of "English Birds". All fished in Lerwick harbour and swarmed on the cliffs of Noss. At close range in summer dress, they were easy to tell apart. My favourite was the Black Guillemot or Tystie which bred within sight of town windows.

In southern haunts after the war, auks became rarities and my youthful confidence in identification wavered distinctly, as I met them only in winter plumage and as far-off blips or dingy strays. It took me 30 years to be sure of the Little Auk or Dovekie – one off Horse Point, St Agnes, in November 1967 ended a hell of a wait! – and, like many others, I never thought to see Brünnich’s Guillemot other than dead on the shore.

Not for me the challenge of spotting a live one in a coastal stream of Guillemots and Razorbills or, for that matter, being sure which was which of those two. So I assumed, but birds have a way of catching you out in such idleness!

From 1972 to 1979 a return to the Herring industry made it inevitable that my seawatches would be full of auks again – and brimming with dissatisfaction over their distant identities. ‘Pesky’ may seem an ungracious word for a splendid tribe of seabirds but it must be put since apart from some discussion of Little Auks and Brünnich’s – no full review of winter auk identification has been attempted.

Perhaps they lack romance, unlike the divers where we have made long strides (fly-by White–billed to go!), and the skuas (totally over-dissected by author after author!) – but nevertheless what a challenge they present. It is time that someone tried. What do we start with?

Auk origins

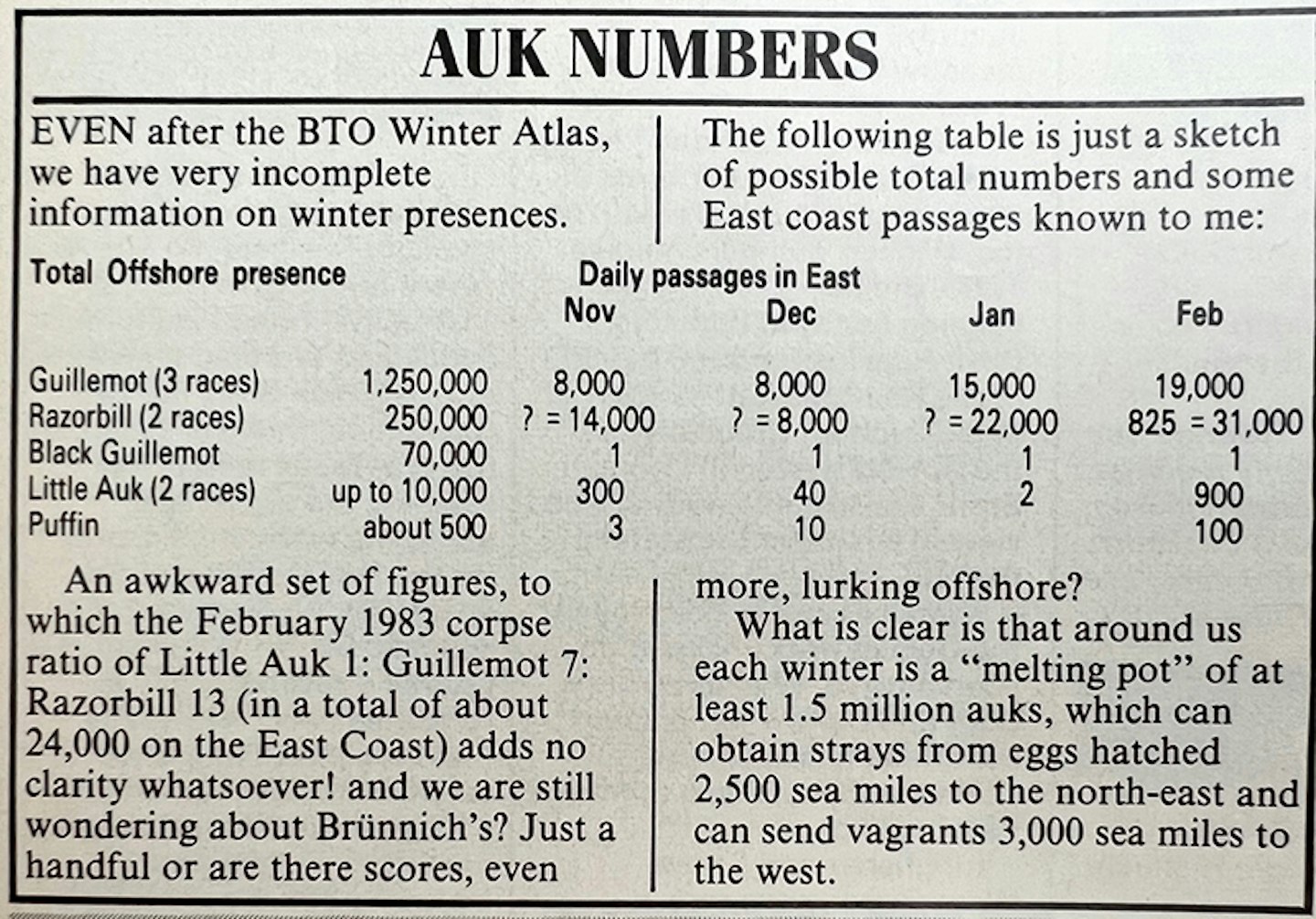

British breeding auks do not go far and even their northern cousins do not "belt south? 9 facing really Arctic conditions with obvious success and not normally moving further south than the ice-free coasts of Norway. In some winters (or food crises), timings are different however, and both corpse measurements and ring recoveries show very complex and far-flung vagrancies and occasional mass movements. These are indicated on the accompanying map.

Auk wrecks

No birds are more washed up than auks. As already noted tideline corpses have told us much about the origins of northern vagrants. The biggest recent wrecks was in February 1983. It was an amazing experience for me to be shown birds with measurements clearly suggesting that they had flown/swam all the way from Franz Josef Land. So never ignore a dead auk!

Why do they die? No one quite knows the sequence of events but occasionally the normally robust, efficient fish-catchers that do ‘fly’ underwater seem to hit thin fish stocks or even barren, over-fished waters. Then, if any piece of really rough weather goes on for too long, the birds run out of "fuel"‘ and hence "steam" before finding a new food source. Onshore wind or drift does the rest. Oiling is an additional hazard in shipping lanes but it is a frequent coup defin (pas de grace!) rather than the basic cause.

New clues at longer range

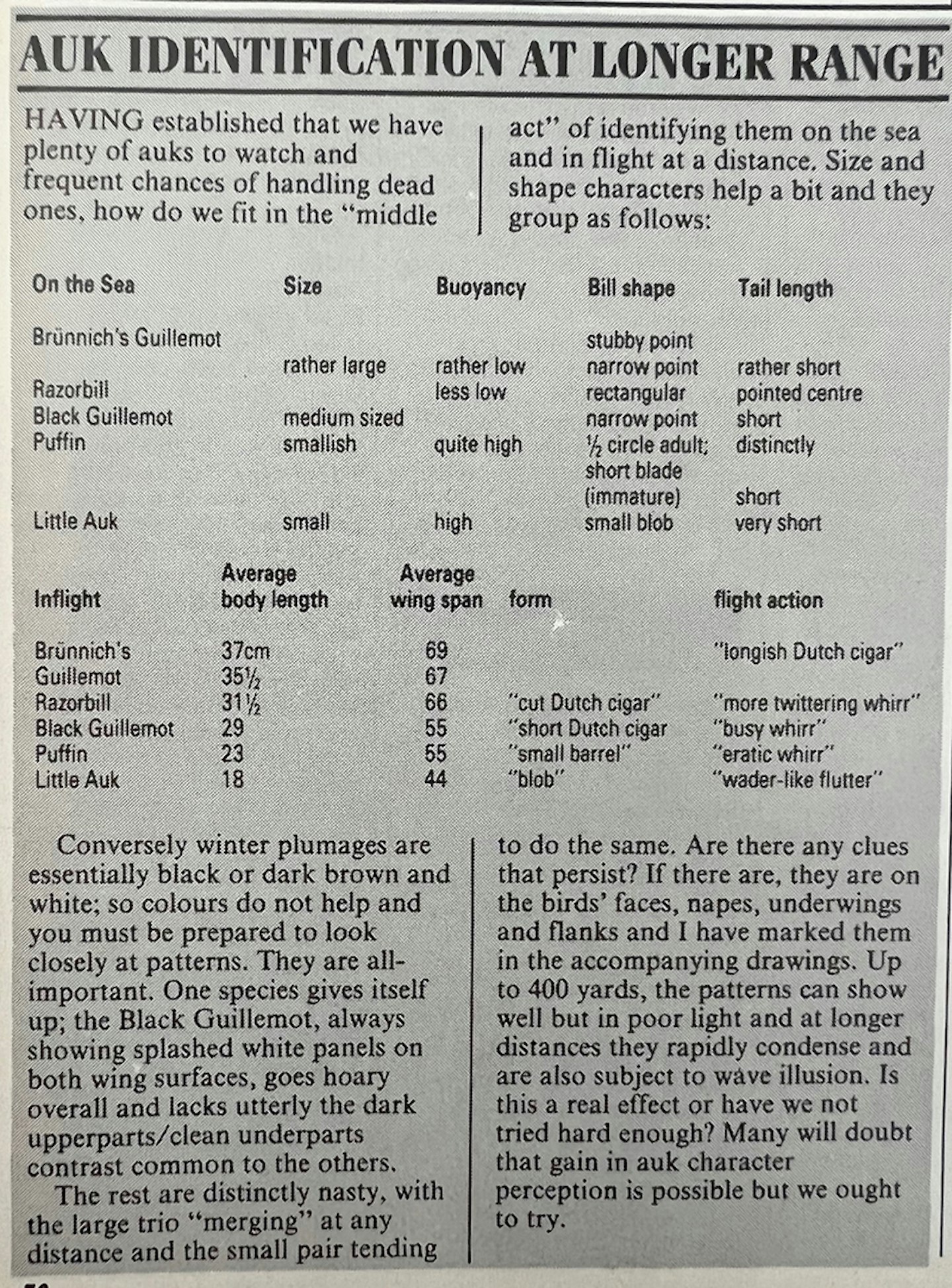

You have to look to see. This is the moral of the long trick to the flight identification of diverse birds such as skuas. In the 1950s, we sweated blood separating them on gravel pits; nowadays a few, really hard-working seawatchers (500-plus hours/year) can do most – of all four – in distant flight (up to a mile). So why cannot we tell distant auks apart? “Because we’re told not to”, is no answer. Here are my thoughts on progress:

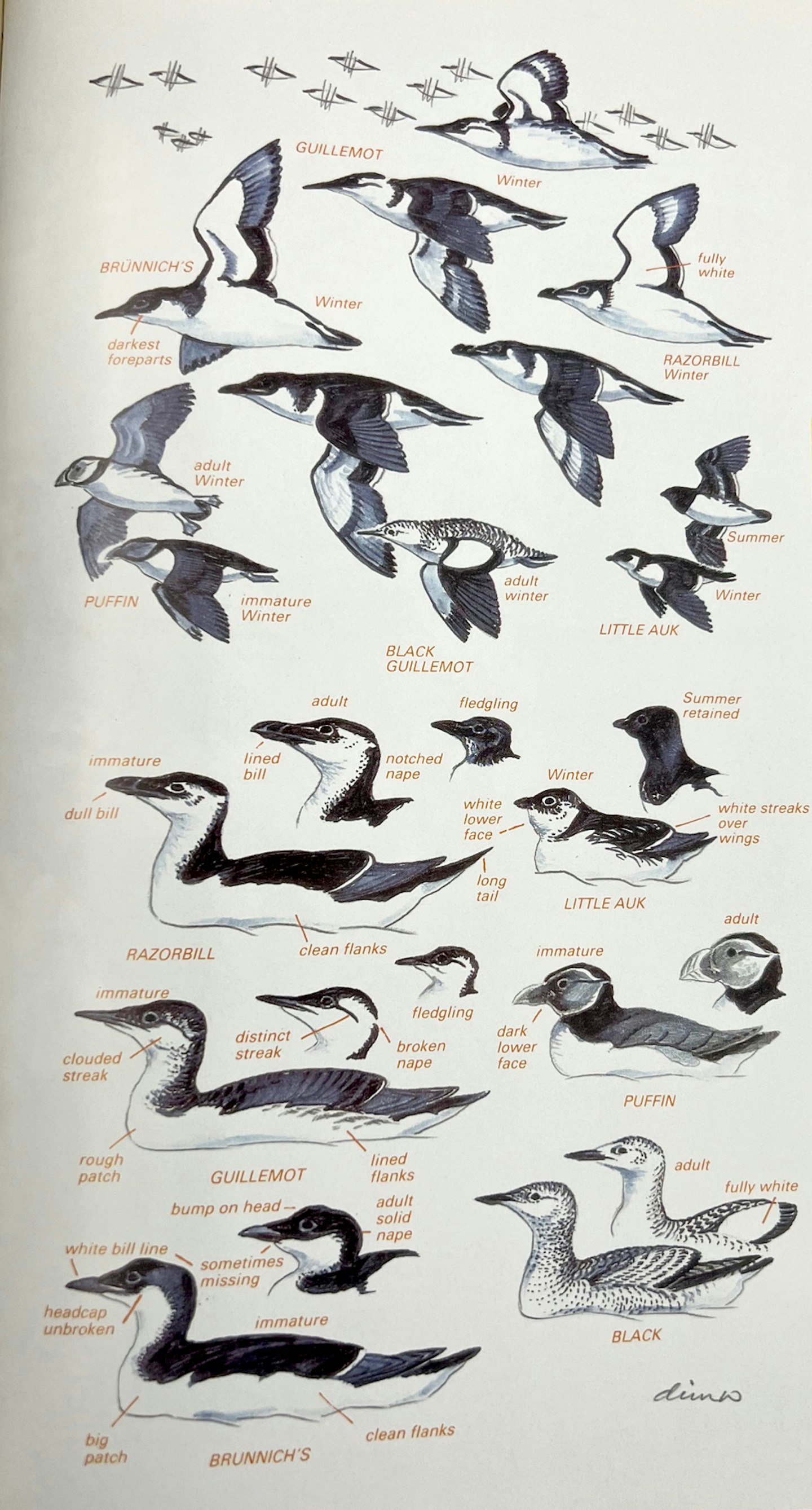

The large trio – Brünnich’s, Guillemot and Razorbill. Weight, wing shape and flight action

Brünnich’s Guillemot is about 25% heavier than Guillemot and the latter is about 10% bulkier than Razorbill. Their wing shapes should compensate for these differences and certainly the three typical wing lengths do follow the same sequence, but only by 7% of Brünnich’s total length.

No hope there; what about breadth? Differences at the wing tip are negligible but at the innermost primary, the breadths again follow the weight order, by 10% of Brünnich’s measurement. Again little hope but as the secondaries of Razorbill are distinctly narrower than its primaries, we can at least isolate its wing shape as relatively short, narrow and paddle-shaped.

That leaves the two guillemots. No certainties but does Brünnich’s have a little more length and flap to its whirr than Guillemot? All three species show similar over-sea speed but does Brünnich’s look rather more powerful?

Flight angle

If Guillemot flies level, does Razorbill proceed slightly tail down? Does Brünnich’s look front heavy? Bill and head bulk This should decrease from Razorbill through Brünnich’s to Guillemot. However, the first seems to fly with its head slightly cocked and drawn back and as Brünnich’s has a gull dark nape, maybe its bill and head look bulkier or more front-heavy? Does Guillemot extend its neck most?

The small pair – Puffin and Little Auk. Weight, wing shape and flight action

Puffin is over 150% heavier than Little Auk but its wings are only 30% longer. Hence a high wing-loading and a particularly rapid and short wing-stroke when taking off and making speed; also an odd habit of changing its lateral body angle as if to catch maximum lift. Yet in spite of its apparently poor design, Puffin makes as much over-sea speed as Guillemot and Razorbill. Not so the Little Auk whose wing-beats, though fast, are actually rather loose and convey more agility in the air than over-sea speed. It is the only auk that can jump from the water surface and unlike Puffin, it frequently suggests a small wader or fluent-flying passerine at long range.

Flight angle

If Puffin flies level, with a front-thick look, does Little Auk proceed slightly head-up/tail-down?

Bill and Head Bulk

Even in its first winter, the mass of Puffin’s bill blade and dusky face is, and looks, deeper than on Little Auk. The latter’s bill disappears at any distance and its head is usually bunched up into its shoulders, although occasionally shooting out on its neck as if increasing the bird’s chance of seeing its way.

This is all very well but are we getting anywhere? Those who have spotted my omission of the small immatures problem in the large trio and Puffin will say “no”. My apologies, but one has to start somewhere, while the only lasting answers will come from your own field trials. Those should begin in July and August at a breeding cliff and with study of the fledglings that hurtle down to their first splash and are then fed on the sea for several weeks.

It may take them up to two months before full flight power, in addition to paddling, takes them away from local food sources. So how many juveniles are on the wing in the later autumn passages? In my opinion, not too many. So the early chances for confusion come mainly from birds on the sea.

Even so, we are still stuck with major problems in separating Brünnich’s, Guillemot and Razorbill – and where do we go to sort them out? Could there be a "Brünnich’s triangle" in the northern sector of the North Sea? I saw a first spring bird halfway between Bergen and Newcastle in March 1977 and at long last we are picking up a few live birds off our coasts. I have also had my suspicions raised by several "lumpy birds" off north-east Grampian but the proof of distribution – and a real chance to perceive the rarest auk – will only come from purposeful voyages. An opportunity for Aberdeen seawatchers to break new water? As I said, it is a real challenge!

Final thought: we witter on and on; "There must be more Brünnich’s than are washed up": I would add: "There ought to be many more Brünnich’s than White-billed Divers!" Down goes a fascinating gauntlet; who will pick it up?

2020s update

Superior optics have improved ID of distant auks to some extent, but there are limits. However, despite improved ID, years like 2021 when there are multiple records of live Brünnich’s Guillemots in UK waters remain extremely rare. White-billed Divers, on the other hand have been found wintering regularly off the coasts of the northern isles, Outer Hebrides and in the Moray Firth.