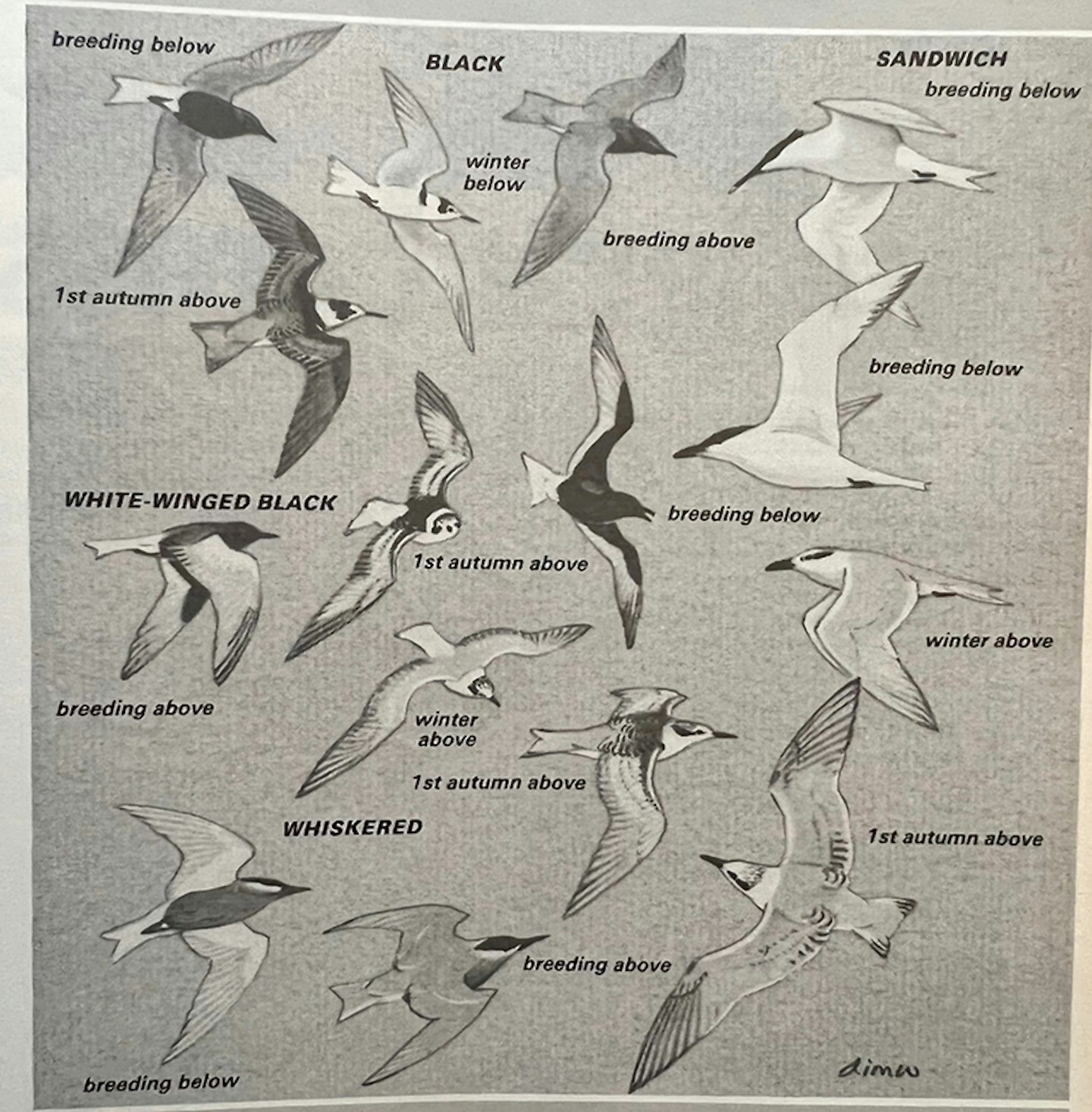

Wetland sprites

July 1987

If there are fairies among birds, the small marsh terns have the best claim to that description. In Britain and Ireland, their spells are frequently cast by their vagrancies and passages. Up to the late 1950s our elders thought only of the Black Tern, but Ian Wallace argues that there are four species to be learnt.

In early September 1959, was using my ex-Kenyan army fieldcraft to survey a ‘no go’ area of Hanningfield reservoir (Essex) when I spotted a marsh tern on a quiet backwater. Little by little, it became not the expected Black. Its dark saddle, pale upper-wing centre and clean shoulders were all wrong for the common species, and it proved eventually to be a young White-winged Black.

A few weeks earlier, the late Ken Williamson had unravelled another at Radipole Lake (Dorset), and from the two came his re-examination of marsh tern identification (and the first of what might be termed the modern series of rarity diagnosis). The advance in knowledge seemed dramatic but what nobody noticed was the fact that the Handbook artist the famous G.E. Lodge had actually painted the differences 20 years earlier. We had all been missing the point because the Handbook text writer, lacking Lodge's visual acuity, had not perceived the true plumage patterns.

The moral is: see for yourself, beware the visions of others!

Four species

Through the 1960s and 1970s records of marsh terns mounted; nowadays they feature regularly in rarity reports. Although there has been some muddying of the waters, their identifications are now among the more secure of uncommon birds. Four species present themselves – three small birds in the genus Chlidonias: Black, White-winged Black, and Whiskered Terns and one medium-large cousin in the genus Gelochelidon: Gull-billed Tern.

The last is one of those strange, patchily-cosmopolitan species whose distribution and existence may be truly ancient; the Black inhabits both the Nearctic and Palearctic, the other two merely the Palearctic.

The west European reclamation of wetlands have forced the four marsh terns into increasingly relict distributions. In our lands, it is 150 years since the Black bred freely in the East Anglian Fens. In recent years only it (in 1970, 1978 and 1983) and the Gull-billed (in 1949 and 1950) have even attempted to breed, with no more than single pairs and a handful of young to show.

Re-occupation is remote, so the marsh terns are seen mainly as spring and summer overshoots or vagrancies and autumn dispersals and passages. At times, the Black is relatively numerous. The spring of 1970 saw 1,500 within southern England; the autumns of 1971 and 1974 produced roosts or passages of over 1000 near South east coasts. Odd Blacks may stray anywhere, even to the northern isles, and the species is the key to its genus. Look long at your first ten examples.

The second commonest Chlidonias is the White-winged Black, which averages more than 15 a year, and whose occasional overshoots of up to 50 spread widely.

The rarest Chlidonias is the Whiskered, which seems to be a better navigator and strays to our waters less than twice a year – a true rarity.

In my opinion, the status of the Gull-billed is clouded. Only four a year are accepted but a few seawatchers see them regularly. They may be commoner particularly in the English Channel.

All the marsh terns, bar the odd laggard, go south for the winter. The Black becomes mainly a seabird, crossing on passage wide stretches of ocean. I once saw 50 in the middle of the Gulf of Guinea. Conversely, the other three species seek out other inland haunts, for example the Niger inundation zone, Lake Chad (or what's left of it), and the East African lakes. They are exceptional on sea coasts.

General character

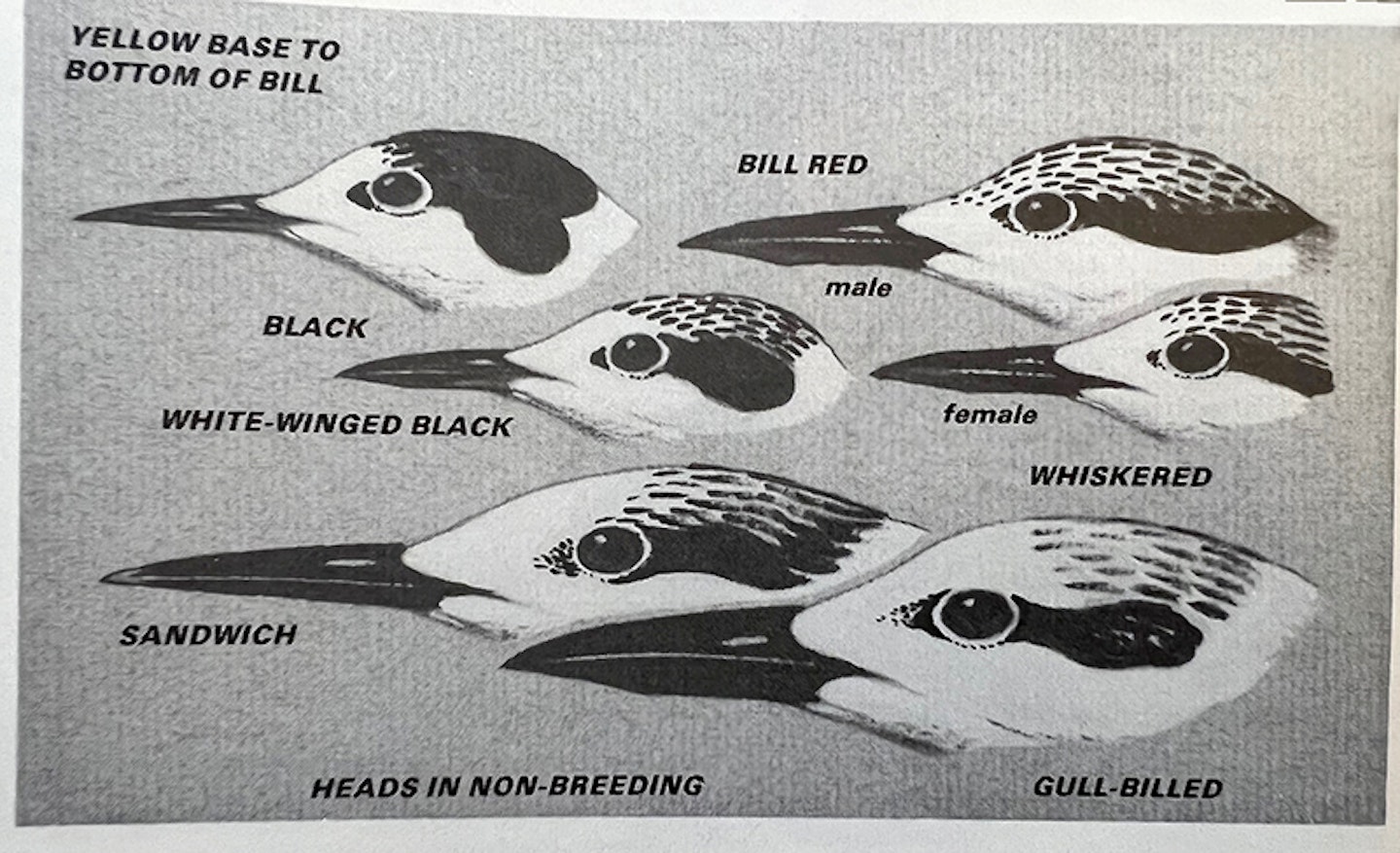

The Gull-billed is the largest of the quartet, looking less slender, broader-winged and shorter-tailed than the Sandwich. Close to, its stubby, but still pointed, bill (not at all that gull-like!) is distinctive, but beware being duped by the shorter, less pale-tipped bill of a young Sandwich. Together, the bill and head look heavy and the whole bird looks weighty. Unlike the sea terns, the Gull-billed rarely dives, capturing most prey by ‘dip, chase, land-and-snatch’ techniques. Small mammals, amphibians and insects are high on its diet sheet. Its flight is lazier than Sandwich and recalls the small marsh terns. A slow, shallow ‘rowing’ action quickens to propel the bird into swoops and lunges. Its rather long legs give it a high-chested stance and an easy gait.

The Whiskered is the biggest Chlidonias with a rather sea tern image granted by its dagger-shaped bill, rather long head and greater wing and leg length. Its commonest feeding stratagem is a ‘hover-plunge’ together with its plumage pattern, its flight action can suggest Arctic but when suddenly the bird dips down or hawks an insect, its true genus strikes you. Like its congeners, its tail looks rather short and a little forked.

In size, the Black and White-winged Black differ little, being 10-15% smaller than Whiskered with less prominent bills, rounder heads and lighter forms. Close to, they exhibit subtle differences in bill shape typically long and fine in Black rather short and stubby in White-winged Black, distinctly tubbier in White-winged wing shape, narrow in Black, lacking the rather blunt wing tip of White-winged and tail shape longer and more forked in Black.

In the White-winged, the differences add up to a resemblance to Little Gull. The Black's slim build goes with a quite energetic flight action, with full wing-strokes obvious in hunting birds. The White-winged's fuller set goes with a more leisurely progress, with shallow wingbeats allowing rather less agility.

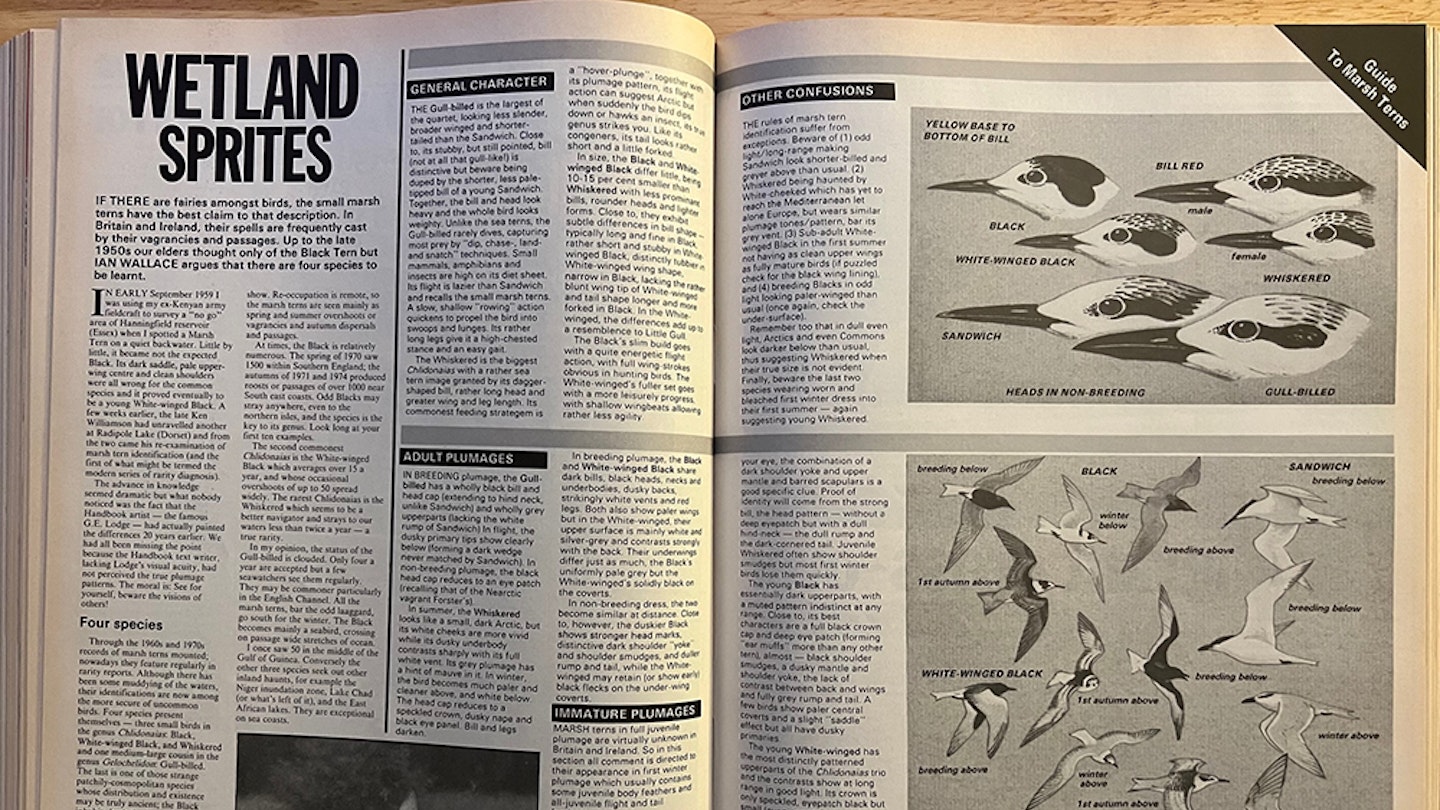

Other confusions

The rules of marsh tern identification suffer from exceptions. Beware of (1) odd light/long-range making Sandwich look shorter-billed and greyer above than usual. (2) Whiskered being haunted by White-cheeked which has yet to reach the Mediterranean let alone Europe, but wears similar plumage tones/pattern, bar its grey vent. (3) Sub-adult White-winged Black in the first summer not having as clean upper wings as fully mature birds (if puzzled check for the black wing lining), and (4) breeding Blacks in odd light looking paler-winged than usual (once again, check the under-surface). Remember, too, that in dull even light, Arctics and even Commons look darker below than usual, thus suggesting Whiskered when their true size is not evident. Finally, beware the last two species wearing worn and bleached first winter dress into their first summer again suggesting young Whiskered.

Adult plumages

In breeding plumage, the Gull-billed has a wholly black bill and head cap (extending to hind neck, unlike Sandwich) and wholly grey upperparts (lacking the white rump of Sandwich). In flight, the dusky primary tips show clearly below (forming a dark wedge never matched by Sandwich). In non-breeding plumage, the black head cap reduces to an eye patch (recalling that of the Nearctic vagrant Forster's). In summer, the Whiskered looks like a small, dark Arctic, but its white cheeks are more vivid while its dusky underbody contrasts sharply with its full white vent. Its grey plumage has a hint of mauve in it. In winter, the bird becomes much paler and cleaner above, and white below. The head cap reduces to a speckled crown, dusky nape and black eye panel. Bill and legs darken.

In breeding plumage, the Black and White-winged Black share dark bills, black heads, necks and underbodies, dusky backs, strikingly white vents and red legs. Both also show paler wings but in the White-winged, their upper surface is mainly white and silver-grey and contrasts strongly with the back. Their underwings differ just as much, the Black's uniformly pale grey but the White-winged's solidly black on the coverts.

In non-breeding dress, the two become similar at distance. Close to, however, the duskier Black shows stronger head marks, distinctive dark shoulder ‘yoke’ and shoulder smudges, and duller rump and tail, while the White-winged may retain (or show early) black flecks on the under-wing coverts.

Immature plumages

Marsh terns in full juvenile plumage are virtually unknown in Britain and Ireland. So, in this section, all comment is directed to their appearance in first-winter plumage, which usually contains some juvenile body feathers and all-juvenile flight and tail feathers.

The young Gull-billed recalls Sandwich but has even more restricted head marks than its winter parent, noticeably plain inner wings (lacking an obvious dusky leading edge), dusky outer wings and dusky brown corner points to the tail.

Whiskered are very rare in autumn and first winter birds are accordingly less well known than those of its two congeners. Like their parents, they can suggest sea terns (in plumage pattern) but close to, once other characters (like flight action) have caught your eye, the combination of a dark shoulder yoke and upper mantle and barred scapulars is a good specific clue. Proof of identity will come from the strong bill, the head pattern without a deep eyepatch but with a dull hind-neck – the dull rump and the dark-cornered tail. Juvenile Whiskered often show shoulder smudges but most first winter birds lose them quickly.

The young Black has essentially dark upperparts, with a muted pattern indistinct at any range. Close to, its best characters are a full black crown cap and deep eye patch (forming ‘ear muffs’ more than any other tern), almost – black shoulder smudges, a dusky mantle and shoulder yoke, the lack of contrast between back and wings and fully grey rump and tail. A few birds show paler central coverts and a slight ‘saddle’ effect but all have dusky primaries.

The young White-winged has the most distinctly patterned upperparts of the Chlidonias trio and the contrasts show at long range in good light. Its crown Is only speckled, eye-patch black but small (even appearing isolated on some), neck collar broad and white, mantle, back and scapulars almost solidly dark, rich brown, showing pale tips only in exceptionally close views – and the wide ‘saddle ‘ so created contrasting vividly with silver-grey centres to dusky rimmed wings, and white rump and tail. Strongly marked birds are unmistakable but a few odd birds have the saddle less uniform and traces of shoulder smudges.