The ways of wagtails

September 1986

ORIGINATING from, and still almost competely confined to the Old World, the 10 species of wagtails Motacilla range across all the length and most of the depth of Eurasia and down most of Africa, shunning only the desert regions of the two continents. In this article, IAN WALLACE discusses the four British species each with its own fascination, and one a real puzzle,

Closely related to the more diverse pipits, the wagtails are relatively small, slender, long-legged insect-eaters, ground loving and sporting long to very long tails which are more or less constantly wagged.

Perhaps the most intriguing question about them concerns those tails: What is their purpose? No-one seems to know, but the clue that I fancy is the correlation of increasing tail length with increasingly rapid and agile food-searching. It could be that the tails are "balancing poles" or "kite streamers" but alternatively it just may be that the family simply needs a "long flag" to enhance display or wave in alarm.

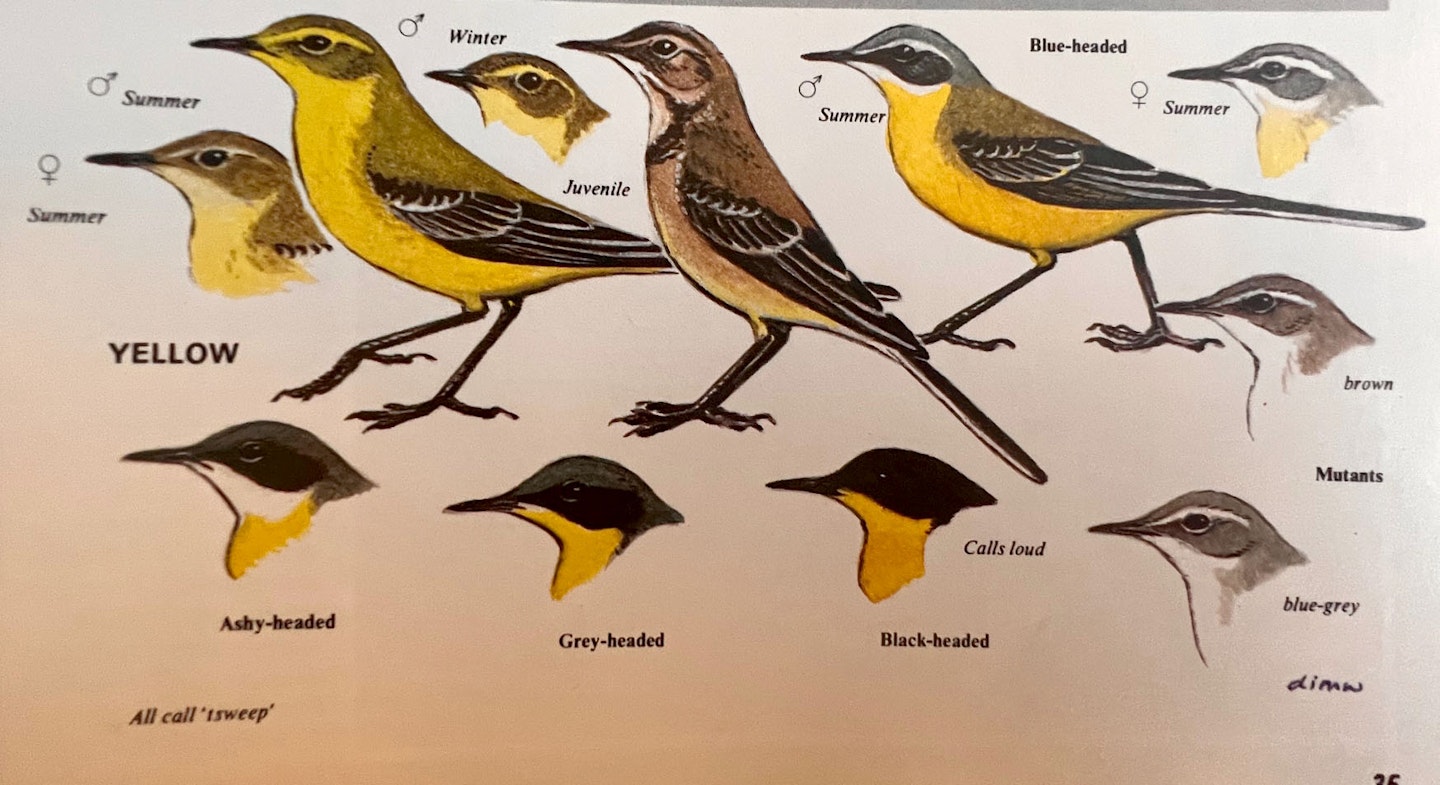

Another intriguing question about wagtails concerns their systematics: Why have the two commonest Palearctic species – the Pied/White and the Yellow/Blue-headed developed between them over 30 subspecies? Such radiation is shown by many terrestrial species but not often to such an amazing and bewildering extent. The answer is apparently a genetic flux caused by:

- The periodic compression and/or separation of basic types by glaciation;

- Their subsequent rapid expansion and/or separation into re-opened or new breeding habitats; and;

- Their constant occupation of common winter quarters which act continually as a melting pot by mixing populations.

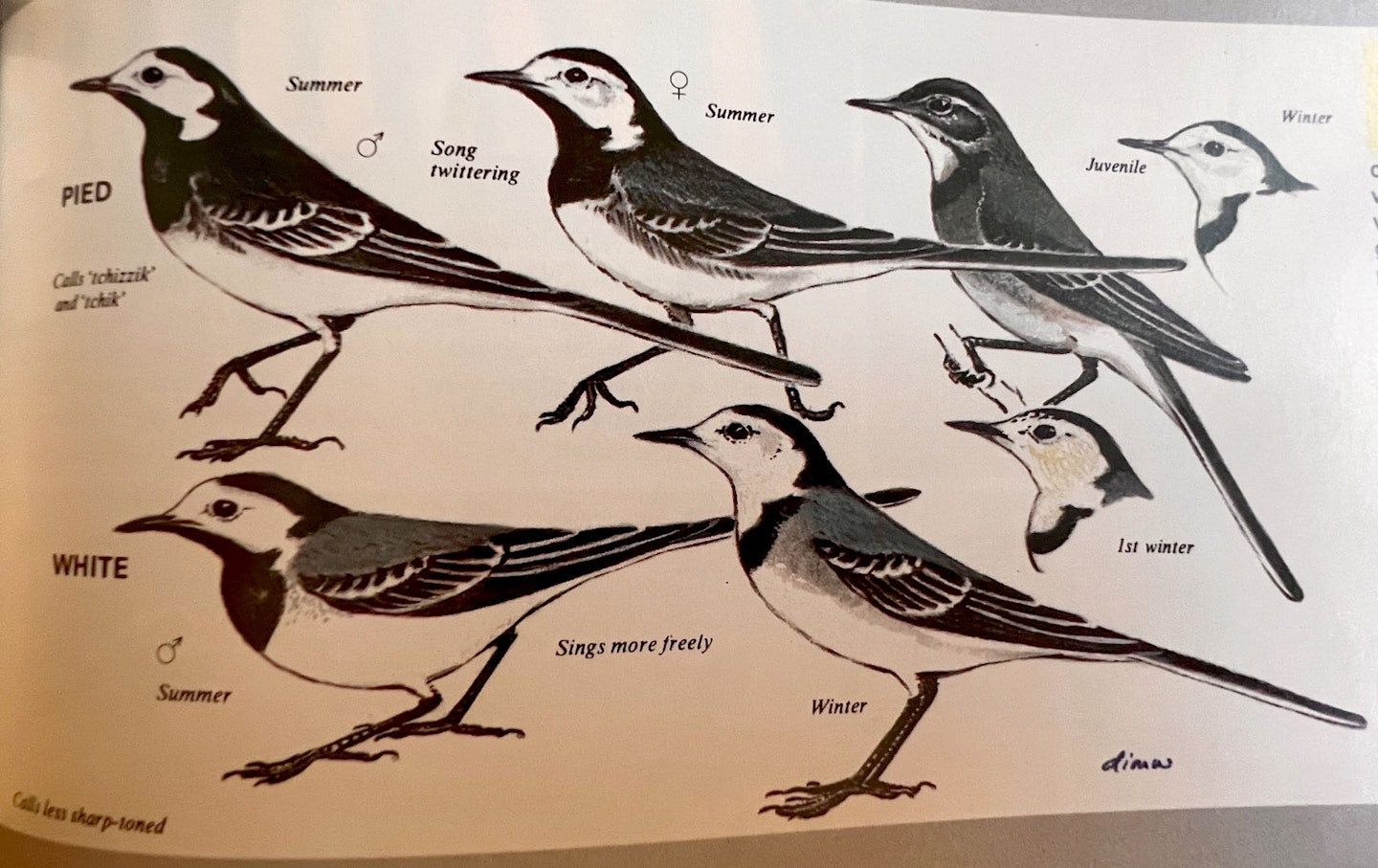

The Yellow/Blue-headed is notoriously unstable, sporting hybrids and mutants where its races overlap (see opposite).

Whatever the true cause, their evolution has given to all male wagtails in the northern hemisphere striking and unusually intensely-coloured plumage patterns, with little of the cryptic (camouflaged) character of pipit dress.

In addition to the Pied/White and Yellow/Blue-headed Wagtails, the Palearctic holds the Grey – the family's aristocratic, with the longest tail and the most specialised habitat requirement of running water and the Citrine – the least widespread with strong hints of a prehistoric Yellow ancestry still evident in its form, behaviour and voice.

Elsewhere in the Old World there are three other pied species – widely separated in Japan, India and Africa and three other relatives of the Grey – all hill birds in central and southern Africa and Madagascar.

The most surprising gap in the grey group's map is the Himalayan mountain range. There, its niche appears to have been usurped in one of the inter-glacial periods by the aberrent thrushes Enicurus, called forktails. In a near-complete convergence of appearance to the Pied/ White these birds have truly pied plumage and long, forked tails that are wagged, also fanned incessantly!

In Britain and Ireland, we face only four species. The Pied/White, Yellow/Blue-headed and Grey breed and the Citrine is a regular vagrant. Nevertheless the complexities of the family, as indicated above, are shown by them all, to the delight and exasperation of bird watchers and ornithologists alike!

Far migrations but close company

The northern and (most) central European populations of wagtails are highly migratory. Starting from winter grounds around the Equator, the Pied/White, Yellow/Blue-headed and the Citrine all fly north to fill up Eurasia and cross the Arctic Circle. Only the Grey, the south-western communities of the Pied/White and a few pocketed populations of the Yellow/Blue-headed are more localised or relatively so. The spring return of wagtails is generally earlier than those of other summer visitors, with the Yellow/Blue-headed particularly prone to travelling rapidly and en masse. Generally the bright males lead their duller mates by as much as two weeks.

The Pied/White's and Yellow/Blue-headed's ability to dash over huge distances is further demonstrated by their recent crossing of the Bering Straits to breed in Alaska.

Their gregariousness in non-breeding seasons is also marked, with the Yellow/Blue-headed and the Citrine forming large roving flocks and all four species assembling at communal roosts containing up to thousands of birds (see opposite).

This behaviour goes beyond mere safety in numbers to real co-operation. What may seem to be widely scattered birds and parties during the day constantly intermingle at night to benefit from the group's knowledge of all the food sources around the roost

Closest to man

Closest to man comes the Pied/White and to which accordingly many vernacular names have been given. Its dramatic plumage pattern, cheerful voice, roof- sitting, hole-nesting and yard and road-running behaviour make it a welcome addition to anybody's local birds.

Of the wagtail quartet, it copes best with suburban and urban habitats and even exploits industrial plant, for example feeding on insects trapped by air intakes and plunging out of the sky to search even the smallest water tank. Its ultimate forte is to have learnt that factories stay

Habitats and breeding behaviour

Although traditionally associated with water and marshes, the wagtails are not wholly dependant on wetlands. They freely use grasslands and cultivated areas for breeding. Thus, for example, the Pied/White has adapted to farms with stock yards, the Citrine freely enters cereal crops and even the Grey with its fondness for fast streams has learnt to cope with stony gullies of the Canary Islands from which all running water is now piped away to irrigate bananas.

Although, again, often thought of as lowland species, all wagtails not just the Grey ascend mountains to breed. The Citrine goes highest, reaching 4,660m in the Himalayas that's a staggering 15,000 feet to my generation!

Of the four species, two – the Yellow/Blue-headed and Citrine are tussock-nesters and two the Pied/White and grey are hole nesters. The last pair will also take over the old nests of other passerines and re-line them. All four lay usually 4-6 eggs and rear one brood, unless the summer ‘window' is long enough for two.

Egg colours are pale, ochre to bluish-white in ground with fine marbling and speckling. Incubation lasts a fortnight and is done mainly by the hens; food provision is the prerogative of the cocks. Family bonds in the immediate fledgling stage are strong, with parents settling young in nearby insect concentrations before attempting a second brood.

Soon to breed

Soon to breed in Britain could be the Citrine Wagtail. Since 1954, its north-west European occurrences have mounted and, like several other passerines from Russia and Siberia, it may be trying to repopulate lands lost in the last Ice Age. Indeed the Citrine may already have bred. In Essex in July 1976, a male brought food to a nest brood of young. By a cruel stroke of birdwatchers' luck, the final clue to the family's full parentage the hen never presented herself for inspection. For me, there was a teasing sequel. In the following May, I was utterly bewildered by a Scilly migrant that was either a young cock Citrine or a hybrid cock Citrine x Yellow.

Subspecies (and systematic headaches)

The large numbers of subspecies, that wagtails are prone to, is best illustrated in the Yellow/Blue-headed tribe. Depending on whether you are a systematic "lumper" or "splitter”. you can choose between nine and 27 races.

For Britain and Ireland, the official BOU List names those tabled. Yellow is a regular summer breeder. Blue-headed is a passage migrant with a few breeding pairs. The rest are rarer or dubious in occurrence.

Latin name; English name; Main breeding range

M. flava flavissima; Yellow Wagtail; UK, extreme W Europe

M. flava flava; Blue-headed Wagtail; Middle Europe

M. flava cinereocapilla; Ashy-headed Wagtail; Italy, Sicily, Sardinia

M. flava beema; Sykes’ Wagtail; SE Russia

M. flava leucocephala; White-headed Wagtail; E central Asia

M. flava thunbergia; Grey-headed Wagtail; Fennoscandia, Russia

M. flava simillima; Eastern Blue-headed Wagtail; Extreme E Siberia

M. flava fedegg; Black-headed Wagtail; Balkans E

The spring bias in vagrant records is incurable, for even males lose much of their distinctive head patterns in autumn and winter, and the attribution of dubious status to the White-headed may well be warranted in the Sykes’ and Eastern Blue-headed. The reason for the hedged bet is the quite frequent mating of "vagrant males to "local" females and one spring later a resultant kaleidoscope of hybrid head patterns, some constant but others not.

The most famous recent British examples came from the colony at Beddington Sewage farm in Surrey, in the late 1950s. They really were the proverbial hybrid swarm! The great thing about these intriguing birds is to keep a clear head. Speaking personally and having watched thousands of flavas on passage and in winter, I am still on balance a "'splitter” and look out for Blue-heads all spring, Ashy-heads in mid May and Grey-heads in late May and June.

2020s update

These days, birds resembling Sykes’ Wagtails (which look like pale-blue-headed Blue-headed Wagtails) are usually given the name ‘Channel Wagtail’ and are considered hybrid birds between Yellow Wagtails (from the UK) and Blue-headed Wagtails from the continent, hence the name Channel, after the halfway point between the two subspecies’ ranges.

Birds from the east of what used to be considered back in DIMW’s day Yelow Wagtails are now usually attributed to the full species Eastern Yellow Wagtail (Motacilla tshutshchensis), and are now considered rare but regular visitors to the UK, with some birds even wintering in recent years.

Some authorities consider birds such as the Black-headed Wagtail to also be of a separate species, but the BOU continues to regard them as conspecific with the rest of the Yellow Wagtial complex.