Tubenose Targets

August 1986

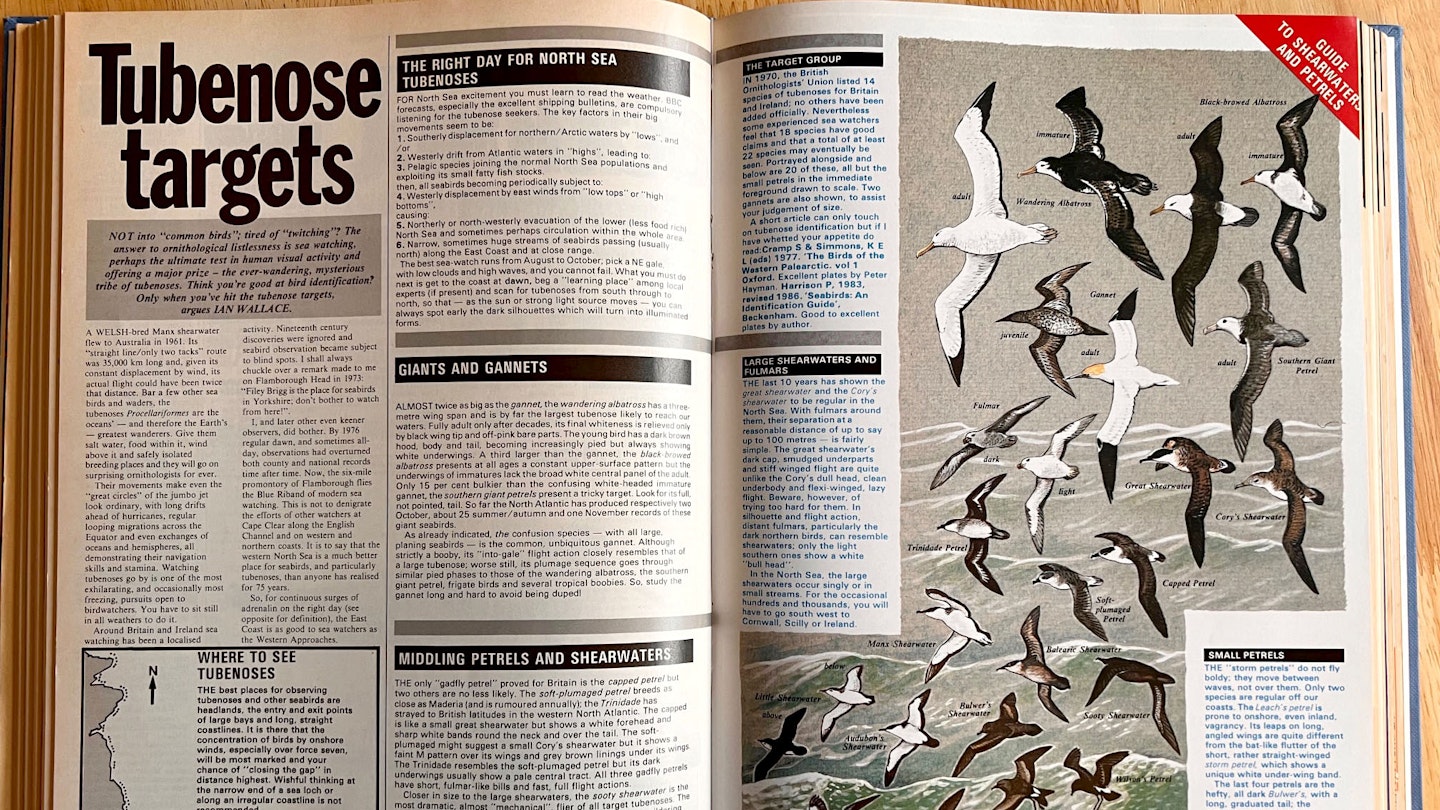

NOT into ‘common birds’; tired of ‘twitching’? The answer to ornithological listlessness is seawatching, perhaps the ultimate test in human visual activity and offering a major prize – the ever-wandering, mysterious tribe of tubenoses.

Think you're good at bird identification? Only when you've hit the tubenose targets, argues IAN WALLACE.

A Welsh-bred Manx shearwater flew to Australia in 1961. Its ‘straight line/only two tacks’ route was 35,000 km long and, given its constant displacement by wind, its actual flight could have been twice that distance. Bar a few other sea birds and waders, the tubenoses Procellariiformes are the ocean’s and therefore the Earth's greatest wanderers. Give them salt water, food within it, wind above it and safely isolated breeding places, and they will go on surprising ornithologists for ever.

Their movements make even the ‘great circles’ of the Jumbo Jet look ordinary, with long drifts ahead of hurricanes, regular looping migrations across the Equator and even exchanges of oceans and hemispheres, all demonstrating their navigation skills and stamina. Watching tubenoses go by is one of the most exhilarating, and occasionally most freezing, pursuits open to birdwatchers. You have to sit still in all weathers to do it.

Around Britain and Ireland seawatching has been a localised activity. Nineteenth Century discoveries were ignored and seabird observation became subject to blind spots. I shall always chuckle over a remark made to me on Flamborough Head in 1973: “Filey Brigg is the place for seabirds in Yorkshire; don't bother to watch from here!”

I, and later other, even keener observers, did bother. By 1976, regular dawn, and sometimes all-day, observations had overturned both county and national records time after time. Now, the six-mile promontory of Flamborough flies the Blue Riband of modern seawatching. This is not to denigrate the efforts of other watchers at Cape Clear along the English Channel and on western and northern coasts. It is to say that the western North Sea is a much better place for seabirds, and particularly tubenoses, than anyone has realised for 75 years.

So, for continuous surges of adrenalin on the right day (see opposite for definition), the East Coast is as good to seawatchers as the Western Approaches.

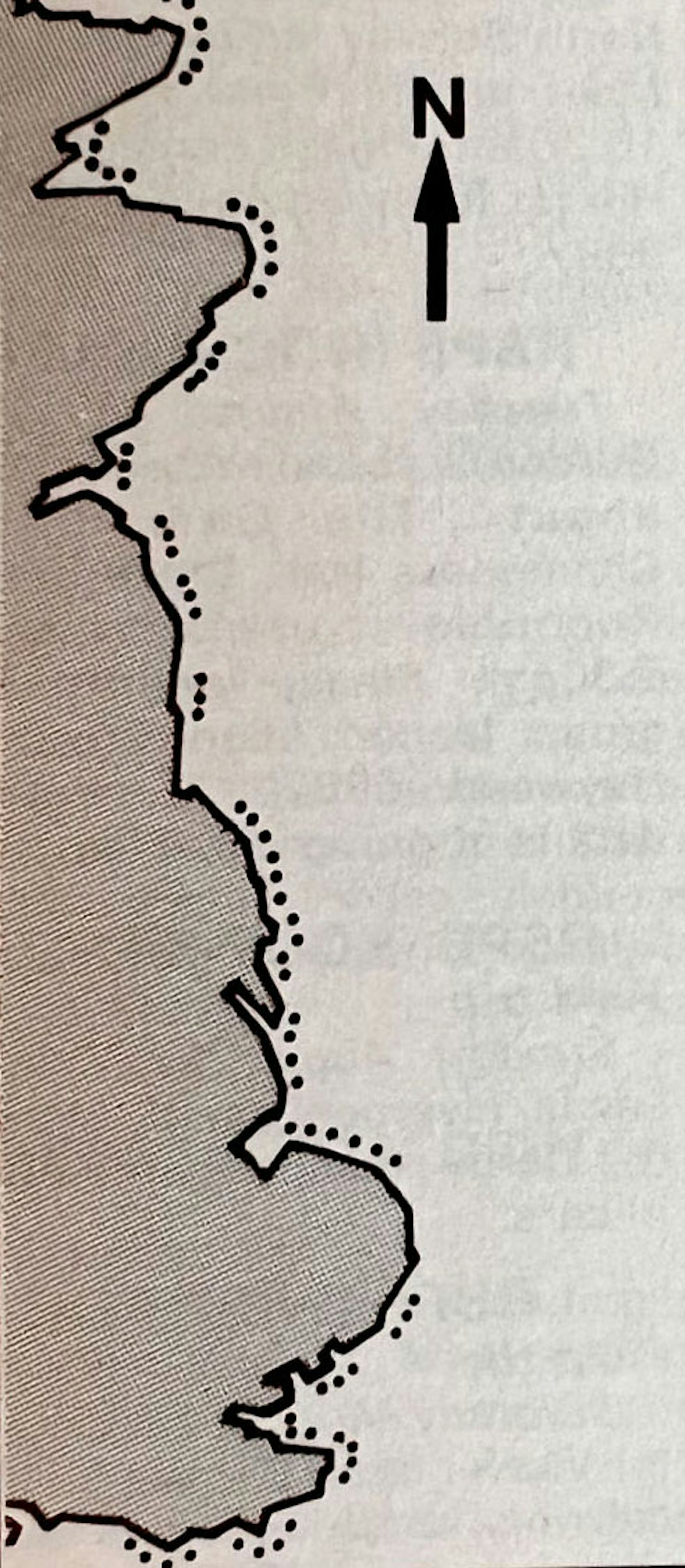

The best places for observing tubenoses and other seabirds are headlands, the entry and exit points of large bays and long, straight coastlines. It is there that the concentration of birds by onshore winds, especially over force seven, will be most marked and your chance of ‘closing the gap' in distance highest. Wishful thinking at the narrow end of a sea loch or along an irregular coastline is not recommended.

Do not watch from the surf-line. Watchpoints as high as 100m are used by the experts. In seawatching, a clear, long view is more useful than a sudden, close, but all too brief, one.

The map (above) shows where seabird passages are concentrated on North Sea coasts.

THE RIGHT DAY FOR NORTH SEA TUBENOSES

For North Sea excitement, you must learn to read the weather. BBC forecasts, especially the excellent shipping bulletins, are compulsory listening for the tubenose seekers. The key factors in their big movements seem to be:

1. Southerly displacement for northern/Arctic waters by ‘lows’ and/or:

2. Westerly drift from Atlantic waters in ‘highs’ leading to:

3. Pelagic species joining the normal North Sea populations and exploiting its small fatty fish stocks. then, all seabirds becoming periodically subject to:

4. Westerly displacement by east winds from ‘low tops’ or ‘high bottoms’ causing:

5. Northerly or north-westerly evacuation of the lower (less food rich) North Sea and sometimes perhaps circulation within the whole area.

6. Narrow, sometimes huge streams of seabirds passing (usually north) along the East Coast and at close range. The best seawatch runs from August to October; pick a NE gale, with low clouds and high waves, and you cannot fail. What you must do next is get to the coast at dawn, beg a ‘learning place’ among local experts (if present) and scan for tubenoses from south through to north, so that as the sun or strong light source moves you can always spot early the dark silhouettes which will turn into illuminated forms.

THE TARGET GROUP

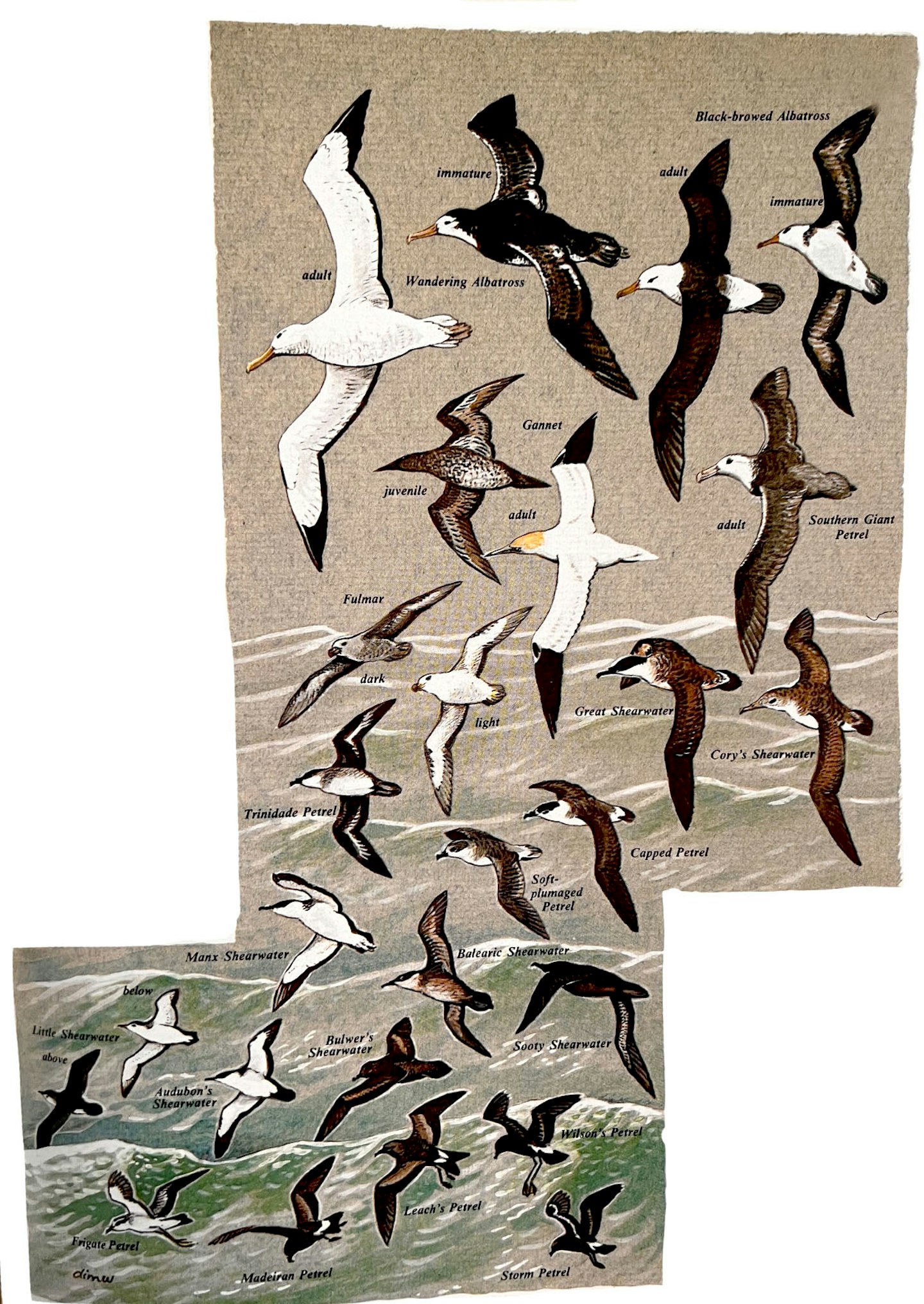

In 1970, the British Ornithologists' Union (BOU) listed 14 species of tubenoses for Britain and Ireland; no others have been added officially. Nevertheless some experienced seawatchers feel that 18 species have good claims and that a total of at least 22 species may eventually be seen. Portrayed alongside and below are 20 of these, all but the small petrels in the immediate foreground drawn to scale. Two Gannets are also shown, to assist your judgement of size. A short article can only touch on tubenose identification but if I have whetted your appetite do read: Cramp S & Simmons, K E L (eds) 1977. 'The Birds of the Western Palearctic. vol 1 Oxford. Excellent plates by Peter Hayman. Harrison P, 1983, revised 1986. 'Seabirds: An Identification Guide', Beckenham. Good to excellent plates by author.

GIANTS AND GANNETS

Almost twice as big as the Gannet, the Wandering Albatross has a 3m wing span and is by far the largest tubenose likely to reach our waters. Fully adult only after decades, its final whiteness is relieved only by black wing tip and off-pink bare parts. The young bird has a dark brown hood, body and tail, becoming increasingly pied but always showing white underwings.

A third larger than the Gannet, the Black-browed Albatross presents at all ages a constant upper-surface pattern but the underwings of immatures lack the broad white central panel of the adult Only 15% bulkier than the confusing white-headed immature Gannet, the Southern Giant Petrels present a tricky target. Look for its full. not pointed, tail. So far the North Atlantic has produced respectively two October, about 25 summer/autumn and one November records of these giant seabirds

As already indicated, the confusion species with all large, planing seabirds is the common, ubiquitous Gannet. Although strictly a booby, its ‘into-gale’ flight action closely resembles that of a large tubenose. Worse still, its plumage sequence goes through similar pied phases to those of the Wandering Albatross, the Southern Giant Petrel, frigatebirds and several tropical boobies. So, study the Gannet long and hard to avoid being duped!

LARGE SHEARWATERS AND FULMARS

The last 10 years has shown the Great Shearwater and the Cory’s Shearwater to be regular in the North Sea. With Fulmars around them, their separation at a reasonable distance of up to say up to 100m is fairly simple. The Great Shearwater's dark cap, smudged underparts and stiff winged flight are quite unlike the Cory's dull head, clean underbody and flexi-winged, lazy flight. Beware, however, of trying too hard for them. In silhouette and flight action, distant Fulmars, particularly the dark northern birds, can resemble shearwaters; only the light southern ones show a white ‘bull head’. In the North Sea, the large shearwaters occur singly or in small streams. For the occasional hundreds and thousands, you will have to go south west to Cornwall, Silly or Ireland.

MIDDLING PETRELS AND SHEARWATERS

The only ‘gadfly petrel’ proved for Britain is the Capped Petrel [Black-capped Petrel] but two others are no less likely. The Soft-plumaged Petrel breeds as close as Maderia (and is rumoured annually); the Trinidade has strayed to British latitudes in the western North Atlantic. The Capped is like a small Great Shearwater but shows a white forehead and sharp white bands round the neck and over the tail. The Soft-plumaged might suggest a small Cory's Shearwater but it shows a faint M pattern over its wings and grey brown linings under its wings. The Trinidade resembles the Soft-plumaged Petrel but its dark underwings usually show a pale central tract. All three gadfly petrels have short, Fulmar-like bills and fast, full flight actions.

Closer in size to the large shearwaters, the Sooty Shearwater is the most dramatic, almost ‘mechanical’, flier of all target tubenoses. The silvery-centred underwing is diagnostic but beware the bewildering variations of the common Manx shearwater, black and white in the Atlantic subspecies but often ‘sooty’ in the Balearic one.

Small, rather than middling, are the two other black and white shearwaters. Both flutter, more like puffins than tubenoses, and the Audubon's has a dark vent and a longer tail than the Little Shearwater. In the early 1980s, the latter visited a Welsh island three years running. Will it breed?

SMALL PETRELS

The ‘storm petrels’ do not fly boldly; they move between waves, not over them. Only two species are regular off our coasts. The Leach's Petrel is prone to onshore, even inland, vagrancy. Its leaps on long, angled wings are quite different from the bat-like flutter of the short, rather straight-winged Storm Petrel. which shows a unique white underwing band. The last four petrels are the hefty, all dark Bulwer's, with a long, graduated tail; the phalarope-like Frigate and, a difficult pair, the Madeiran which zig-zags on flat wings and the Wilson's with legs so long that its feet trail behind its tail. Their British and Irish records do not exceed 20, but there must have been more. Will you spot the next?

2020s update

There are now 18 species of tubenose on The British List as compiled by the BOU: Wilson’s Petrel, White-faced Storm Petrel, Black-browed Albatross, Atlantic Yellow-nosed Albatross, Storm Petrel, Swinhoe’s Petrel, Leach’s Petrel, Fulmar, Black-capped Petrel, White-chinned Petrel, Scopoli’s Shearwater, Cory’s Shearwater, Sooty Shearwater, Great Shearwater, Manx Shearwater, Yelkouan Shearwater, Balearic Shearwater, and Barolo Sheawater.

The most recent addition was White-chinned Petrel, seen and photographed over Scapa Bay, Mainland, Orkney on 25 May, 2020.

Of the birds on the list of tubenoses above, Barolo Shearwater used to be called Little Shearwater. The species Manx Shearwater used to also encompass the browner Mediterranean birds, now ‘split’ further as Balearic and Yelkouan Shearwaters (as well as Manx Shearwater, of course).

Atlantic Yellow-nosed Albatross is on The British List, after an immature rescued from Brean Down, Somerset, in late June 2007. After release, it crossed the country NE, and was relocated at Manton Lincolnshire in early July 2007.

As hinted at by DIMW, gadfly petrels (in the genus Pterodroma) are now a regular part of the UK seawatching scene. They are difficult to pin down to species, at sea, but it is thought most sighted are Fea’s Petrels. There have been convincing recent claims of Zino’s Petrel and Soft-plumaged Petrel; and all three will surely be on The British List, soon.

There have been recent, convincing claims of giant petrels off the east coast, though not seen close enough to tie down to exact species (Northern and Southern Giant Petrels are very similar at any distance).

Wilson’s Petrels are, these days seen regularly invariable numbers, particularly in the ‘Wilson’s Triangle’ visited by pelagic boat trips off the Isles of Scilly.