Spirits of the high tops

July 1986

If there is true wilderness left in Britain, the summits and steep inclines of the Welsh, English and Scottish mountains have a strong claim to it. Quite high, wet, windy and occasionally very cold, they experience the clash of maritime and Alpine climates; their most visible inhabitants are some superb birds. Seventeen upland species are described here by Ian Wallace – hill boy before birdman and still including high top days in every bird watching year.

With so many birdwatchers dashing about our lowlands for rarities, who remembers the time when their ornithological ancestors and many landed gentry spent time and resources on science and management for sport of much less chancy bird communities? In the 19th Century, none drew more attention than the grouse and deer- bearing Highlands; and up to the 1930s, their natural predators were cruelly put down.

Thereafter the tide of human opinion turned and, particularly since the near debacle of toxic chemicals, man has seen the birds of the high tops as precious indicators of a healthy upper world. Furthermore, most journeys after them are truly adventurous, because if you are to step over mainland wilderness in Britain, then up you must climb.

The effort, for the true ornithologist, is well spent, as each step or heave focuses the mind a little bit more and each ridge or summit brings not only interesting birds but also a sharp sense of their brief but rich summer ecology. Not for brief pleasure did hill bird students, like the late Desmond Nethersole-Thompson or the still striding Adam Watson, climb mountains in all weathers.

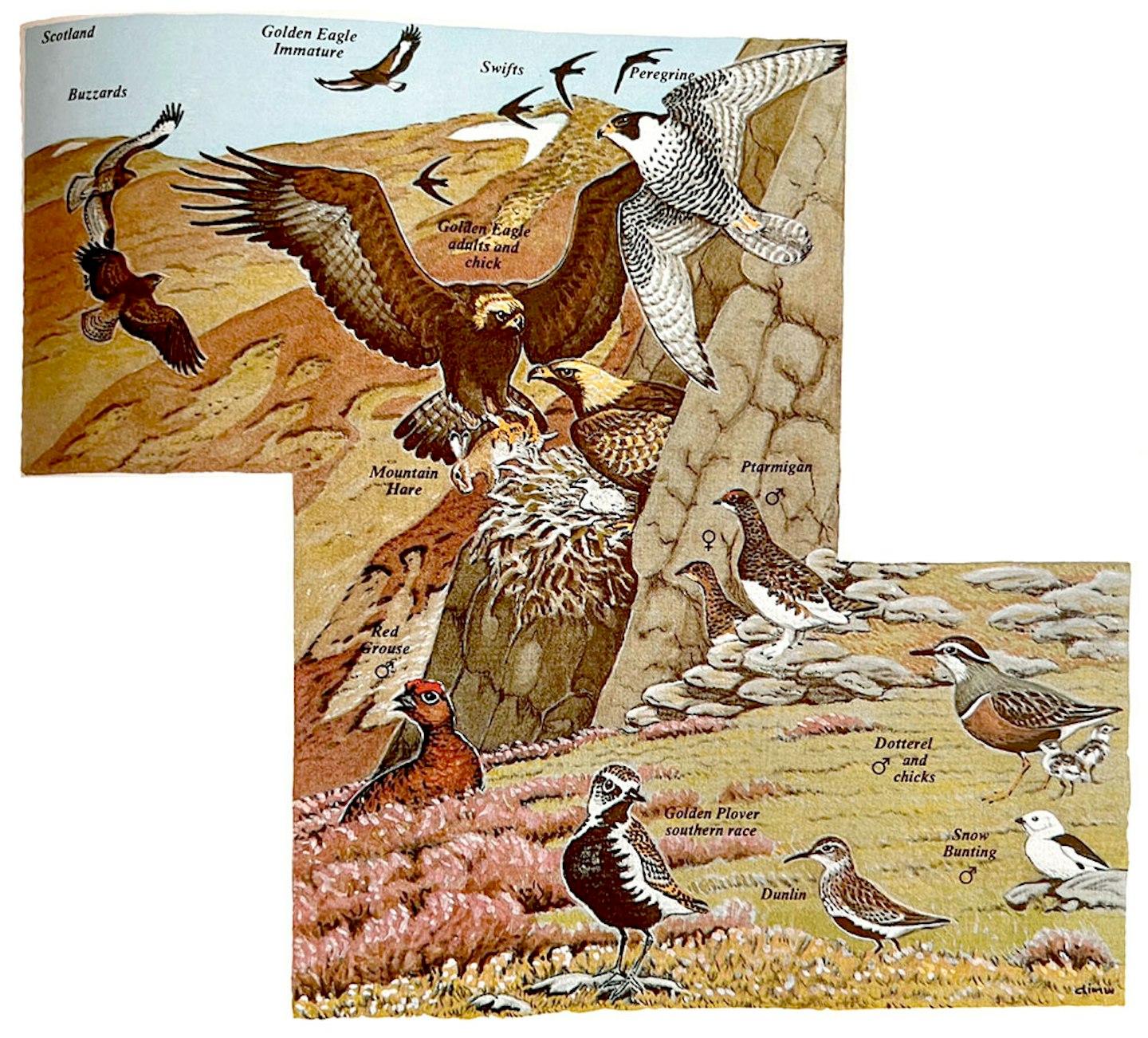

It is debatable whether Britain has real mountains, but their mix of ancient tundra and extreme climate at relatively low altitude allows us to enjoy both montane and Arctic birds in an essentially low and temperature country. Among them are world precious populations of Golden Eagles and Peregrines, two circumpolar grouse, three sparkling waders and several distinctive songbirds, all more fully discussed below.

Since the late 1960s, ski lifts have made it easier to reach the Scottish mountain peaks. But never disturb rare hill birds. Their ‘summer window’ of warmth and plant or invertebrate food is the shortest in Britain and they need every moment of it for breeding success.

Over high, wide horizons

Over high, wide horizons in all of the West Country wheels the Buzzard, and in north and west Scotland soars the Golden Eagle. Both serve not just as noble decoration, but also as evidence of abundant prey on healthy land. Britain is fortunate to have retained viable populations of these large raptors. Two centuries of unthinking game managers, ill-informed agriculturists and Rabbit plagues took heavy tolls of them. But for the ban on dangerous sheep dip in 1966, their numbers might have dropped below the point of no return.

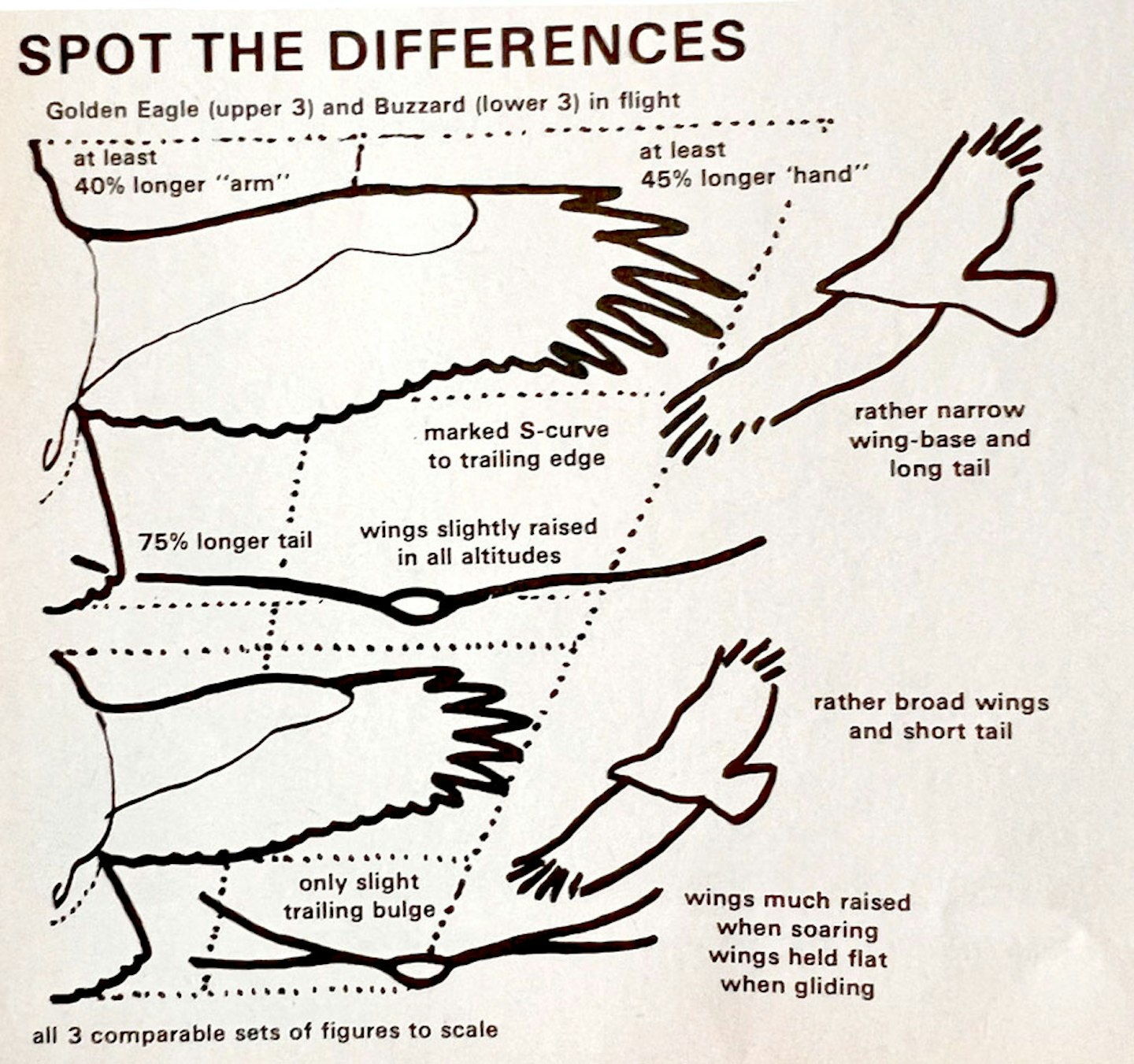

Nowadays, the Buzzard population aided by more and more Myxomatosis-resistant Rabbits seems set to top 10,000 pairs again and the Golden Eagle could hold 250-300 pairs. The latter reoccupied the Lake District in 1969 and vagrants stray even further south. A pair's hunting may cover 7,000 hectares. A "rushed tick" could cost a wet, cold eaglet the most important hare meal of its life. So PLEASE tread carefully on eagle ground! Telling Buzzards from Golden Eagles can be tricky (see the plate and size diagrams).

The swift is now a "house- hold" bird but its primeval niche was tree and cliff cavities, in Asia as high as 2,000 metres. Over Britain, feeding birds regularly reach 1,000m and when the high tops swarm with insects in summer, the "black screamer comes to fill its food pouches.

The topmost grouse

The topmost grouse is the Ptarmigan, whose Arctic-Alpine heath distribution rings the Arctic Ocean. In Britain. it occupies the highest breeding niche of all birds. Scottish mountain tops between 760 and 1,240m and displays there an Arctic lifestyle, digging snow holes and munching berries in autumn. Prone to high chick death in wet years, the population struggles to reach 10,000 pairs and finds range expansion difficult, though Arran was re-occupied by a sea crossing in the 1970s. A favourite prey of eagles, the Ptarmigan's defence includes camouflage. It changes its plumage three times a year, becoming ermine white in winter.

On high moors and screes

On high moors and screes, the diversity of birds is low but then characterisation is distinct and colourful. On such ground in central and north Scotland, two grouse, three waders and at least one Arctic passerine may present themselves.

Of the grouse, the red grouse is not as typical of summits as the Ptarmigan but some of the 400,000 pairs will breed as high as 900m. Once thought to be our one endemic species, the red is actually a dark race of the willow grouse but its ecological significance in Britain remains high. It causes more wilderness. management than any other animal, with "high bags demanding both the generation of young heather-tips (staple diet and the preservation of old heather clumps (shelter) in the same moor.

On the flatter tops from May to early July are found most of Britain 's 30,000 pairs of Golden Plover, 6,000 pairs of Dunlin and 200 pairs of Dotterel. Known to most bird watchers only as dowdy birds, all three present richly-coloured breeding plumage in early summer. Simulating Arctic tundra, the Scottish high tops also catch the odd Arctic passerine. The most regular is the snow bunting, known sporadically from a dozen or so rocky massifs. In a good year (after a cold spring), up to six breeding pairs occur.

Well back from the brink

Well back from the brink is the Peregrine, its return the happiest achievement of Britain's bird conservers. From 1956 to 1962. Toxic chemicals in its food chain rapidly made the hold of this superb falcon on Britain as fragile as it still is in most of its range. By 1971, new regulations had enforced care with pesticides and a recovery was visible.

On top fells and hillsides

On top fells and hillsides, particularly in central and north Wales, the most interesting passerine is that bright crow, the Chough. Although nowadays associated with encliffed coastlines in the west and north of Ireland and Britain, that distribution reflects more the two centuries of range contraction than the bird's true niche. The Chough is really a mountain bird (and I shall never forget the thrill of finding two at the peak of Snowdon). No bird enjoys itself and its fellows' company more. Perhaps 30 pairs still breed inland, even in slate quarries.

The Merlin is in trouble. Our smallest, yet most exciting, falcon has not recovered from a chemical-sullied environment. As few as 500 pairs may now breed and they are being disturbed by the march of conifers and people.

Of the other passerines that reach the high tops, the finest is the Ring Ouzel declining but still with 8,000 pairs coming back from a Mediterranean winter. The prettiest is the wheatear - ten times commoner than the thrush and, like the chough, a truly montane species in most of its range. Comparatively abundant with three million pairs each over all Britain, are the skylark and the meadow pipit. Both breed as high as 1,000m. Indeed over 500m, the pipit is the only common passerine - hosting hill Cuckoo chicks and feeding merlin fledglings!

Drawing first on its cleanest "cells" in Scotland, the Peregrine is re-charging its ‘battery’ everywhere. Passage and winter birds are again widespread. To think of 700, even 1,000 pairs, is possible again. Totally fearless, Peregrines will "see off" anybody eagles not excepted. It is a crime that Britain's 500 remaining egg collectors and eyass [a downy raptor]salesmen with an eye for Arab wrists and money still prey upon them.

Safe in Wales?

Safe in Wales is the question always asked about the Red Kite. Exterminated from Scotland, England and north-west France in the late 1800s, this raptor has hung on in west central Wales. Only a dozen survived in the early 1900s but with the dedication of generations of kite wardens and the occasional inflow of European vagrants, the population has slowly grown. It reached 42 pairs in 1985.

Sadly, this year has again seen egg thefts from at least five nests but the RSPB seems confident that Britain 's most beautiful bird of prey will survive. However, it will not return to scavenge the streets of London!

2020s update

Probably the most remarkable change in these upland bird populations has happened to the Red Kite. Thanks to a hugely successful reintroduction programme started in the late 1980s and 1990s Red Kites are now a very familiar sight across much of the country. Indeed in some areas they are now the most frequently seen bird of prey. The UK breeding population is at least 4,600 pairs and they are found in all sort of country, often well away from mountains, even including flat country like the fens of East Anglia. Indeed, even if they don’t (yet) scavenge in the streets of London, kites will come down to people’s gardens to pick up scraps!

Second in striking population expanses is the Buzzard, which has moved from its West Country stronghold to occupy most of the country, and is now regarded as the UK’s most abundant raptor with up to 80,000 pairs breeding each year (that is eight times the population in 1986).

The Peregrine has continued its population recovery from DDT poisoning, and now some 1,500 pairs nest in the UK, many in low country, including several pairs occupying tall buildings such as churches, cathedrals and power station sin the east of the UK.

Golden Eagle snow number about 440 pairs; Dotterel are up to 750 pairsl; and Chough have more than 350 breeding pairs, including some back in Cornwall.