Britain's and Ireland's coasts throng with seabirds in summer; nowhere more so than along the sea cliffs that protect the northern and western coasts of our countries and overlook dense, small-fish populations. Some cliffs form veritable seabird cities and provide great birdwatching from March to August. In this article, Ian Wallace takes you down a typical cliff to reveal its avian affairs.

In the late 1960s, birdwatchers made a huge co-ordinated effort – called Operation Seafarer – to measure the seabird populations of Britain and Ireland. When all the journeys and boat trips were over, the total number of breeding pairs was put at more than 3 million (or a third of all the non-passerines in Britain and Ireland).

In the last 20 years, there have been some bad seabird days – all oil spills are such, but in general, they appear to be doing well. Their summer mass may now be over 3.3 million pairs, the vast majority in Scotland and Ireland and very few in south-east England.

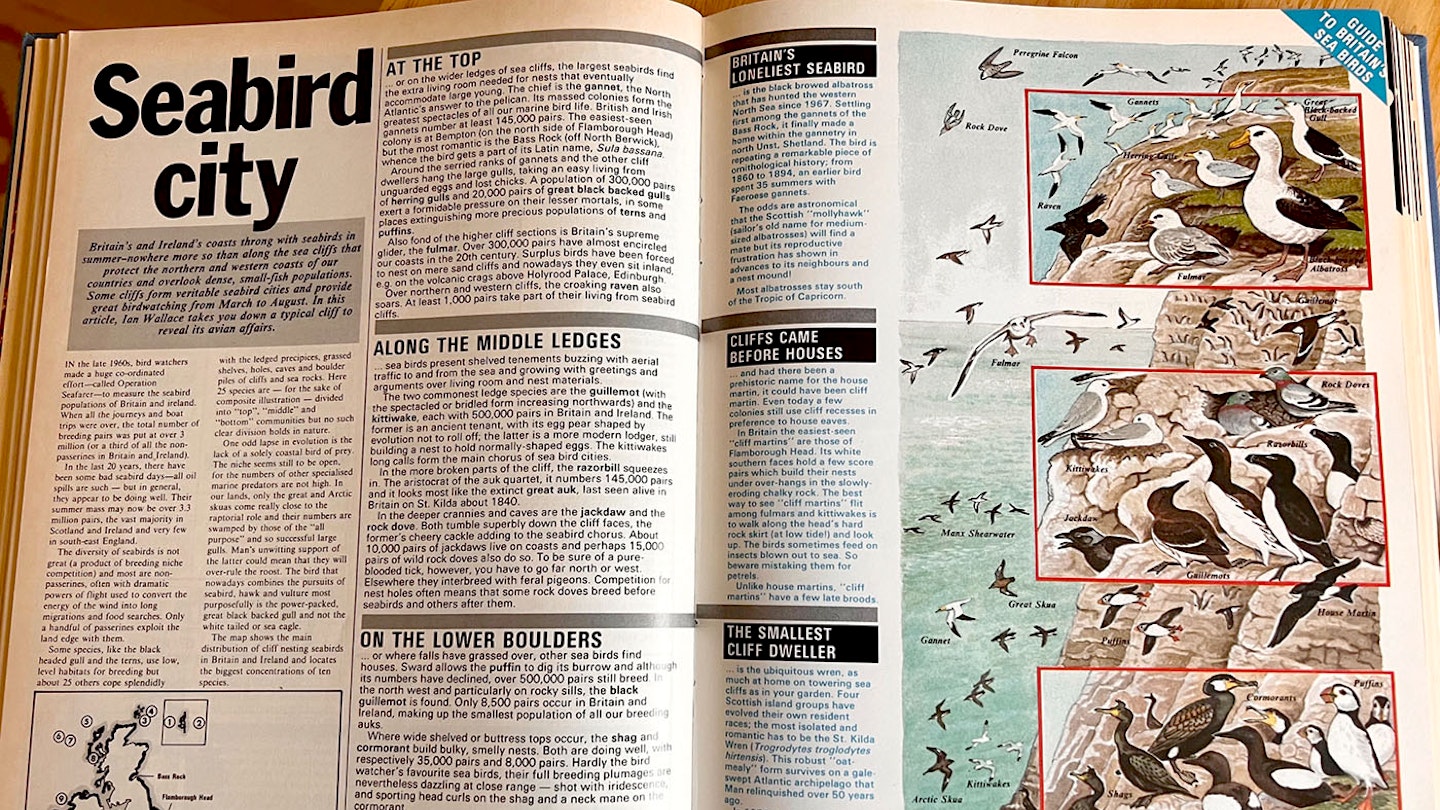

The diversity of seabirds is not great (a product of breeding niche competition) and most are non-passerines, often with dramatic powers of flight used to convert the energy of the wind into long migrations and food searches. Only a handful of passerines exploit the land edge with them. Some species, like the Black-headed Gull and the terns, use low, level habitats for breeding but about 25 others cope splendidly with the ledged precipices, grassed shelves, holes, caves and boulder piles of cliffs and sea rocks.

Here 25, species are for the sake of composite illustration divided into ‘top’, ‘middle' and 'bottom’ communities but no such clear division holds in nature.

One odd lapse in evolution is the lack of a solely coastal bird of prey. The niche seems still to be open, for the numbers of other specialised marine predators are not high. In our lands, only the Great and Arctic Skuas come really close to the raptorial role and their numbers are swamped by those of the ‘all purpose’ and so successful large gulls.

Man's unwitting support of the latter could mean that they will over-rule the roost. The bird that nowadays combines the pursuits of seabird, hawk and vulture most purposefully is the power-packed, Great Black-backed Gull and not the White-tailed Eagle. The map shows the main distribution of cliff-nesting seabirds in Britain and Ireland and locates the biggest concentrations of 10 species.

Main distribution of cliff-nesting seabirds in Britain and Ireland. The numbers locate ten particular concentrations.

At the top

At the top or on the wider ledges of sea cliffs, the largest seabirds find the extra living room needed for nests that eventually accommodate large young. The chief is the Gannet, the North Atlantic 's answer to the pelican. Its massed colonies form the greatest spectacles of all our marine bird life. British and Irish Gannets number at least 145,000 pairs.

The easiest-seen colony is at Bempton (on the north side of Flamborough Head) but the most romantic is the Bass Rock (off North Berwick), whence the bird gets a part of its Latin name, Sula bassana.

Around the serried ranks of Gannets and the other cliff dwellers hang the large gulls, taking an easy living from unguarded eggs and lost chicks. A population of 300,000 pairs of Herring Gulls and 20,000 pairs of Great Black-backed Gulls exert a formidable pressure on their lesser mortals, in some places extinguishing more precious populations of terns and Puffins.

Also fond of the higher cliff sections is Britain's supreme glider, the Fulmar. Over 300,000 pairs have almost encircled our coasts in the 20th Century. Surplus birds have been forced to nest on mere sand cliffs and nowadays they even sit inland, e.g. on the volcanic crags above Holyrood Palace, Edinburgh. Over northern and western cliffs, the croaking Raven also soars. At least 1,000 pairs take part of their living from seabird cliffs.

Britain’s loneliest seabird

Britain’s loneliest seabird is the Black-browed Albatross that has hunted the western North Sea since 1967. Settling first among the Gannets of the Bass Rock. it finally made a home within the gannetry in north Unst, Shetland. The bird is repeating a remarkable piece of ornithological history; from 1860 to 1894, an earlier bird spent 35 summers with Faroese Gannets. The odds are astronomical that the Scottish "mollyhawk" (sailors’ old name for medium-sized albatrosses) will find a mate but its reproductive frustration has shown in advances to its neighbours and a nest mound! Most albatrosses stay south of the Tropic of Capricorn.

Along the middle ledges

Along the middle ledges sea birds present shelved tenements buzzing with aerial traffic to and from the sea and growing with greetings and arguments over living room and nest materials The two commonest ledge species are the Guillemot (with the spectacled or bridled form increasing northwards) and the Kittiwake, each with 500,000 pairs in Britain and Ireland. The former is an ancient tenant, with its egg pear shaped by evolution not to roll off; the latter is a more modern lodger, still building a nest to hold normally-shaped eggs.

The Kittiwakes long calls form the main chorus of sea bird cities. In the more broken parts of the cliff, the Razorbill squeezes in. The aristocrat of the auk quartet, it numbers 145,000 pairs and it looks most like the extinct Great Auk, last seen alive in Britain on St Kilda about 1840. In the deeper crannies and caves are the Jackdaw and the Rock Dove.

Both tumble superbly down the cliff faces, the former's cheery cackle adding to the seabird chorus. About 10,000 pairs of Jackdaws live on coasts and perhaps 15,000 pairs of wild Rock Doves also do so. To be sure of a pure-blooded tick, however, you have to go far north or west. Elsewhere they interbreed with Feral Pigeons. Competition for nest holes often means that some Rock Doves breed before seabirds and others after them.

Cliffs came before houses

Cliffs came before houses and had there been a prehistoric name for the House Martin, it could have been Cliff Martin. Even today a few colonies still use cliff recesses in preference to house eaves. In Britain, the easiest-seen "cliff martins" are those of Flamborough Head. Its white southern faces hold a few score pairs which build their nests under over-hangs in the slowly- eroding chalky rock. The best way to see "cliff martins" flit among Fulmars and Kittiwakes is to walk along the head's hard rock skirt (at low tide!) and look up. The birds sometimes feed on insects blown out to sea. So beware mistaking them for petrels. Unlike House Martins, "cliff martins" have a few late broods.

On the lower boulders

On the lower boulders, or where falls have grassed over, other sea birds find houses. Sward allows the Puffin to dig its burrow and although its numbers have declined, over 500,000 pairs still breed. In the north west and particularly on rocky sills, the Black Guillemot is found. Only 8,500 pairs occur in Britain and Ireland, making up the smallest population of all our breeding auks. Where wide shelved or buttress tops occur, the Shag and Cormorant build bulky, smelly nests.

Both are doing well, with respectively 35,000 pairs and 8,000 pairs. Hardly the birdwatcher's favourite sea birds, their full breeding plumages are nevertheless dazzling at close range - shot with iridescence, and sporting head curls on the Shag and a neck mane on the cormorant.

By the sea, among weed wrack and boulders, the Rock Pipit finds food for young in nests placed above the spray line. A total of 50,000 pairs exploit our coasts; those of the north and west have evolved into a dark sub-species.

Particularly in the north west, sward and rock holes accommodate the other British tubenoses, the Manx Shearwater with perhaps 300,000 pairs: the Storm Petrel with perhaps 50,000 pairs and the Leach's Petrel with at least several thousand pairs. All three visit their nests only at night but some Manxies the North Sea are just offshore during the day, even in the North Sea.

The smallest cliff dweller

The smallest cliff dweller is the ubiquitous Wren, as much at home on towering sea cliffs as in your garden. Four Scottish island groups have evolved their own resident races; the most isolated and romantic has to be the St. Kilda Wren (Troglodytes troglodytes hirtensis). This robust mealy , form survives on a gale- swept Atlantic archipelago that Man relinquished over 50 years ago. In 1956, I recorded the voice of the St. Kilda Wren for the BBC and envied the tiny birds' confidence on the near-vertical 1,000 feet and more cliffs of Hirta. That particular island's population exceeds 100 pairs but the total for the group is probably below 200 pairs, making T.t. hirtensis a truly rare being!

2020s update

The UK Gannet (now called Morus bassanus) breeding population has now risen to an estimated 220,000 pairs.

Herring Gull UK breeding pairs now number about 140,000, while there are c17,000 pairs of Great Black-backed Gull.

Fulmar breeding populations have risen to 500,000 pairs.

Guillemot populations have nearly doubled to 950,000 pairs and Black Guillemot now has 19,000 breeding pairs in the country.

Kittiwake numbers have reduced to 380,000 pairs.

The Storm Petrel now has about 25,000 breeding pairs and the Leach’s Ptrel close to 50,000

A Black-browed Albatross has recently become an annual summer visitor once again to the UK’s cliffs and waters, this individual being mainly seen in the Gannet colony at Bempton Cliffs, Eat Yorkshire