Colourful colonisers

May 1986

More finches have reoccupied Britain as a breeding or wintering ground than any other group of passerines. At times of high population density - as in the late 1970s - finches form the most abundant bird family in our lands. Here IAN WALLACE examines their diversity of species and subspecies

FINCH is a name applied widely to passerine birds throughout the world and at least 11 families bear it. Their primary characteristic is a strong, pointed beak which, combined with enlarged head muscles, allows hard seeds to be broken and their kernels extracted. Britain's 15 breeding and five visiting finches – compared to 42 species in the Palearctic – is impressive, bearing witness to the bird's ability to travel far en masse, reoccupy lost habitats and use most niches within them. Indeed, their actual diversity, relative to their potential diversity, is the highest of any British song bird family that has come back since the last Ice Age.

Within Britain and Ireland, ten to 12 million pairs of finches are present in summer. Nearly three-quarters of them are Chaffinches of the resident British race, which vies with the Blackbird and the Wren to be our commonest bird. The next most numerous are the Greenfinch (one million pairs); Linnet (800,000 pairs), Bullfinch (600,000 pairs) and Goldfinch (300,000 pairs). They and most of the other scarcer or rare breeding species are partial or occasional migrants. At least 21 million finches leave our shores in autumn and hard weather, and their daily passages over headlands are often dramatic. However their exodus to France and Spain is much obscured by similarly - timed immigrations or irruptions of continental birds looking fur 'open ground' or fleeing food failures.

Within the big movements, the incidence of scarce migrants and rare vagrants is insignificant; most finches are truly common birds. The breeding biology of British finches shows quite marked generic differences. The Fringilla pair (Brambling and Chaffinch) dispute large territories, in which they feed, lay four to seven eggs and usually raise only one brood in about 26 days. The larger Carduelinae sub-family are far less territorial. share food sources, lay three to six eggs, and frequently raise more than one brood in 20-28 days.

Surprisingly, the shortest cycle is that of the relatively huge Hawfinch, and the three Loxia crossbills are also exceptional in nesting early, beginning in late winter. Further exploration of the fascinating finch behaviour will be greatly assisted by reading lan Newton's excellent Finches (Collins 1972).

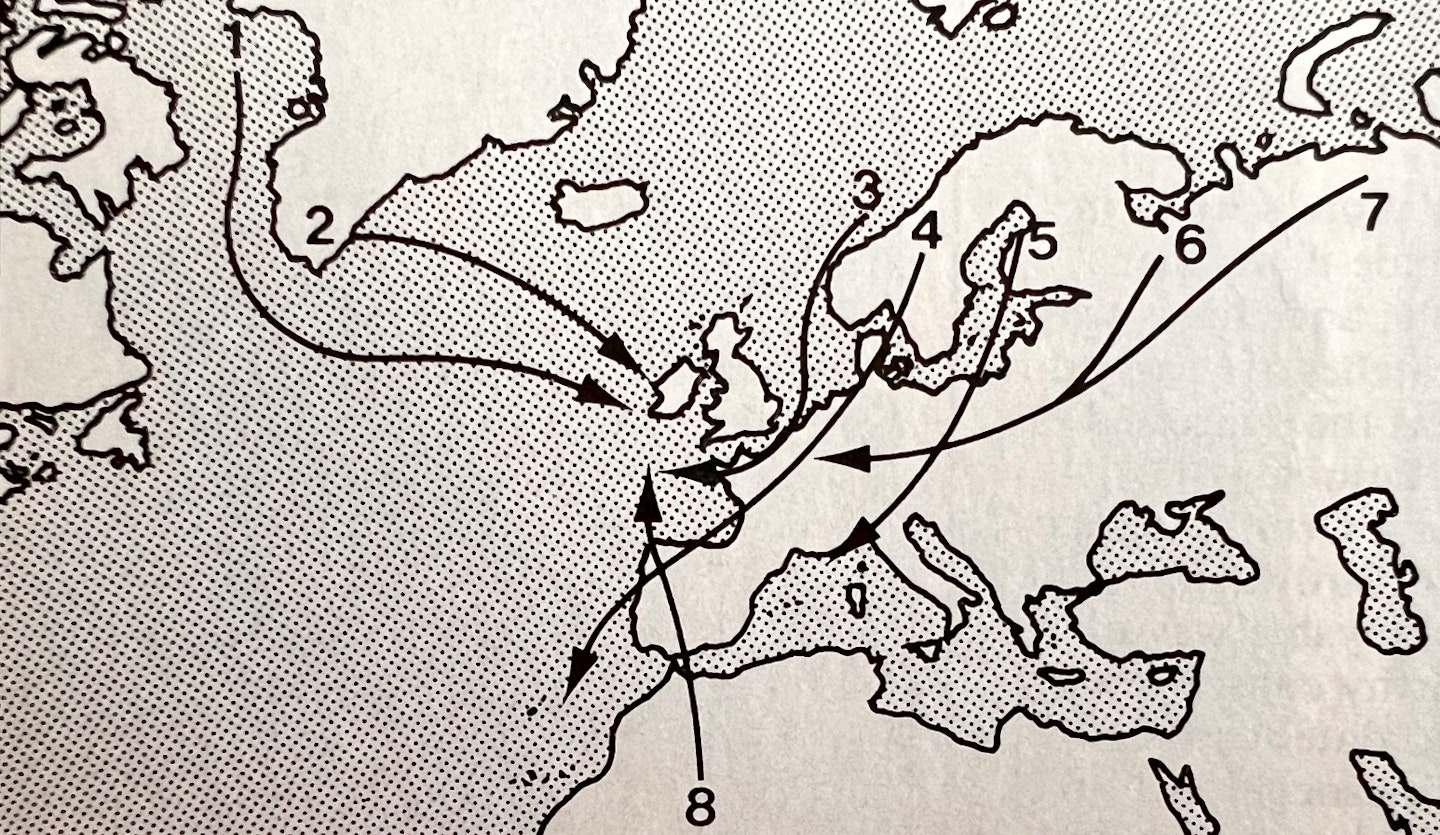

The origins of finches reaching Europe and Britain are far flung, bridging the north Atlantic. Look at the map for the approach routes of (1) and (2) redpolls from Greenland; (3) and (4) chaffinches, ramblings, siskins and redpolls from Norway and Sweden; (5), (6) and (7) irruptive species, especially crossbills, from Finland to the Urals, and (8) the trumpeter finch from north Africa.

NORTHERLY BREEDING SPECIES

include the Brambling which has been tempted by recent weather to linger, and the Siskin, which has been spreading south since the 1960s and is now learning to be fed by man. Next comes the Twite (alias the ‘Mountain or Coastal Linnet’), which is the only representative of the Tibetan avifauna in Europe, and the Lesser Redpoll which increased rapidly during the 1970s. Also included are the Scottish Crossbill; the Parrot or Pine Crossbill, nesting once after the 1984 irruption; and the Scarlet (aka Common) Rosefinch,'sniffing’ like the Brambling at a Scottish extension to its Eurasian range.

'Northerly' is not a precise habitat term so 'coniferous forest’ is a better ecological common denominator of these seven finches, except the Twite which requires Alpine tundra or equivalent maritime habitat. The Twite is also the only one of this group not to wear sexually dimorphic plumage for breeding. The bright cocks do not all have full or melodious songs. Their most tell-tale calls are: the 'chucc- chucc-chucc' of the Brambling the piercing 'tsu-ee" of the Siskin the nasal 'chweck' of the Twite; the insistently muttered 'chit-tit tit' of the Lesser Redpoll; the ringing 'chop-chop of the Scottish and the deeper 'kop-kop of the Parrot Crossbill; and the 'twick' or "twee-cek° of the Scarlet Rosefinch, whose song is the flintiest of this group (even recalling the Golden Oriole).

SOUTHERLY BREEDING SPECIES

...are the Hawfinch which is found everywhere but on high lands; the Goldfinch which is predominantly a summer visitor to southern Scotland; the Serin which is now hauling itself abroad from France; the Bullfinch which is absent from the far North; and the Common or Spruce Crossbill which has long been a periodic immigrant to southern conifers. The Chaffinch is truly widespread, but even it shuns most Scottish Isles. Again 'Southerly' is not a precise habitat term and 'deciduous woodland and scrub' would be a better common denominator for all except the Crossbill. Hedgerow loss is doing harm only to the Linnet, which like the Whitethroat, has become scarce and patchy in many farm lands.

Six of the southerly species wear sexually dimorphic (different) plumage and again their songs are variable quality. The male Goldfinch is by the best songster, in fact good enough to rival the canary. Is that why he does not differ in appearance from his mate? The most diagnostic calls of this group are the springtime "swee of the Greenfinch; the liquid 'swit- wit-wit-wit "' of the Goldfinch; the rippled 'tirrilit' of the Serin; the hollow but far-carrying 'then' of the Bullfinch; the emphatic' "chup- chup of the (Common) Crossbill and the well known 'pink' of the Chaffinch. It is important to remember that although flight notes remain constant, other finch calls vary by season.

VAGRANTS VIS NA

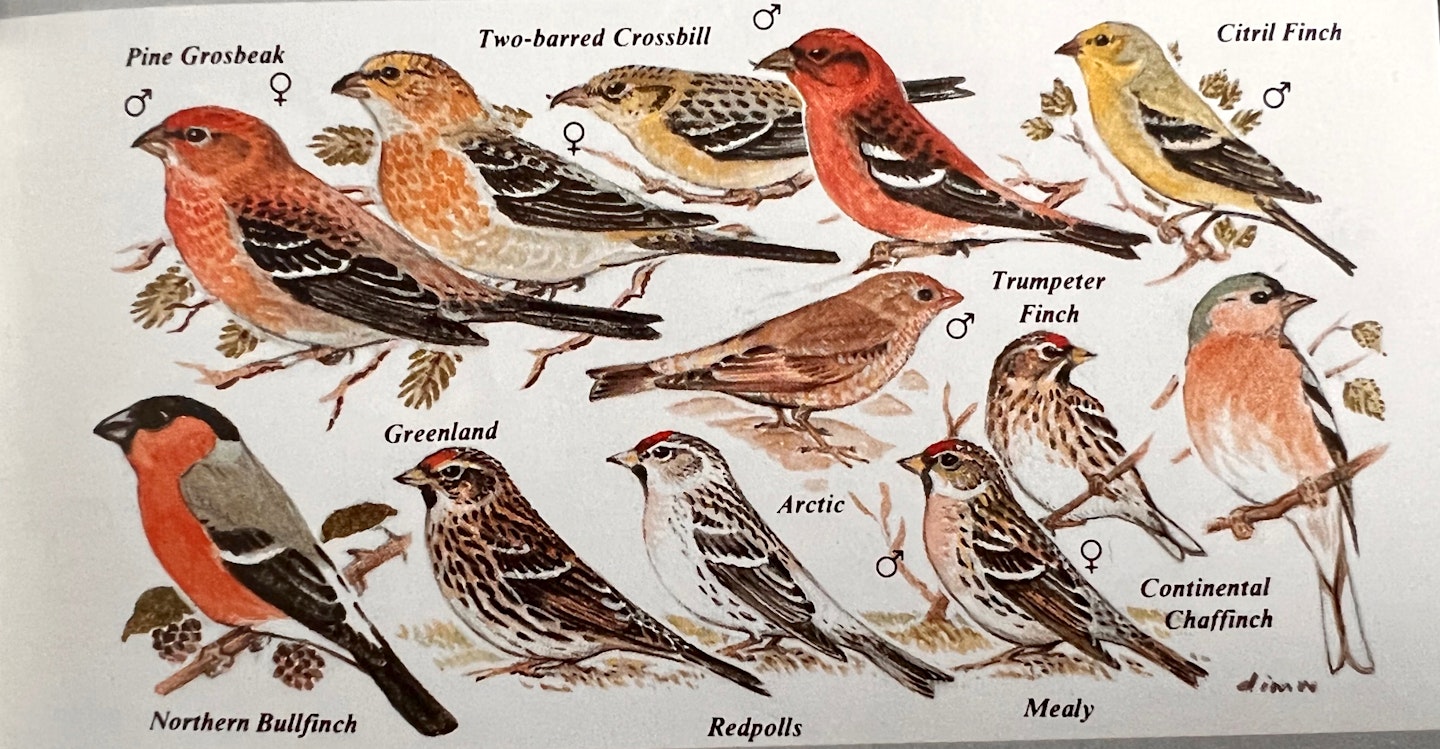

fall roughly into three groups, but finch migration is complex, with much overlapping and intermingling of breeding and winter communities. The most clearly recognisable (but difficult to forecast) group is the irruptive quartet of the hoary Mealy Redpoll, the ghostly Arctic Redpoll, the Northern Bullfinch and another classic taiga bird, the Two-barred or Larch Crossbill. Stemming from Finno-Scandia and north Russia, the first three occur annually - the last big invasion of the red-polls was in 1984 - but the last is a true rarity, infrequently trailing the regular incursions of the Common Crossbill.

The second but often obscured group comprises the European contingents of three breeding species, the cold not warm-pink Continental Chaffinch, and the Fenno-Scandian Brambling and Siskin. Their immigrations can be large, with millions of Chaffinches on the move through October days. The third group is more a miscellany with only the Greenland Redpoll at all regular and the odd Arctic Redpoll (of the Canadian race), the large Pine Grosbeak – yet another taiga finch, the Trumpeter Finch from North Africa – and the Citril Finch are all truly rare.

The problems of identification in migrant finches are tricky, and for a good tease, the redpolls come second to none. The two species intermingle at first sight and hybridise; as already indicated the Arctic comes in two races, the other in at least three. You'll need keen eyes and excellent wits to sort them out.

SCOTLAND'S OWN BIRD

…is no longer the Red Grouse, now demoted to sub-species ranking. However heretical the transfer may seem to a certain whisky distiller, the title has now passed to the Scottish Crossbill. After years of systematic debate, it now ranks as a full species, between the Parrot and the Common Crossbill. Its long isolation in the remaining Scots pine woods and its middle-sized beak (scaled to efficiently break into pine cones) are the two main reasons for its promotion. The maturing of post-war conifer plantations has encouraged the bird to spread out its Rothiemurchus Forest stronghold in the Highlands, but unlike the Common, it is still a rather sedentary bird with a more regular breeding cycle.

THE SECRET GOLIATH

...is the Hawfinch. Weight for weight, no other British bird packs more muscle power around such a strengthened skull and beak. Its seed-cracking vice can exert a 100lb load, easily smashing cherry stones, and yet the whole bird weighs only two ounces. However strong, the Hawfinch is shy and elusive, so it is a far more challenging quarry than most rarities. It breeds deep in woods and orchards and the untidy, flimsy nest platform supports four or five eggs which hatch in 11 to 13 days. The young fly in 12-14 days and two or three broods are the rule. Learn the Hawfinch's 'tzik-ic' notes and watch for small parrots' dashing over canopies. These are the most frequent clues to their presence.

DOWN FROM THE ALPS

...comes the beautiful Citril Finch, but its normal post- breeding movements are either merely altitudinal or short trips of no more than 300km. Hoping to see the only bird endemic to the Alps in Britain has to be classed as a truly Arthurian quest. It is a long 82 years since one of the many former East Coast bird-catchers trapped a female at Great Yarmouth on a January morning. If you want to see a cock Citril Finch in its superb breeding plumage your better best is to get above 1,500m in the Alps or onto the high tops of Corsica and Sardinia. If you want to see the bird in winter, the coasts of those islands are full of them.

DIM Wallace wrote this article in the mid-1980s, and although his advice remains excellent, much has changed in UK bird populations in recent decades. Here are some of the more significant changes since this feature was originally published in BW

2020s update

Current estimated breeding populations of UK finches (in pairs)

Chaffinch: 6.2 million

Greenfinch: 1.7 million (significant increase since 1986)

Linnet: 430,000 (nearly 50% decline since 1986)

Bullfinch: 190,000 (65% decline since 1986)

Goldfinch: 1.2 million (a huge increase over the 300,000 in 1986)

These days the Redpoll is ‘split’ into the common Lesser Redpoll and the relatively scarce Common Redpoll (which includes the Mealy Redpoll). Arctic Redpolls also come in two distinct taxa, the Hornemann’s Redpoll and the Coues’s Redpoll. The latest research has demonstrated very little genetic diversity within the whole complex, and it seems likely that all the redpolls (including Arctic) will be lumped together once again.