Starting up on Stints

September 1987

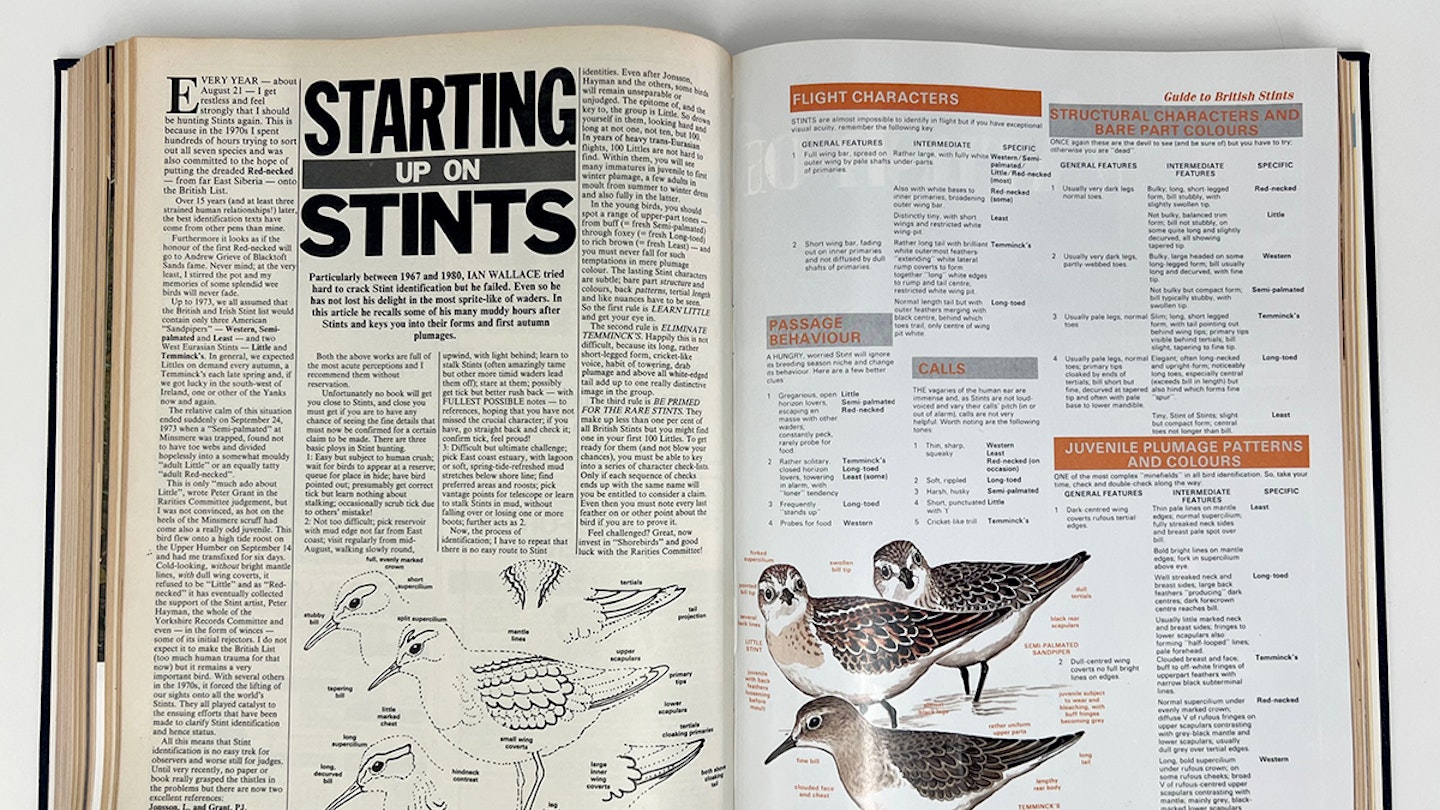

Particularly between 1967 and 1980, IAN WALLACE tried hard to crack stint identification, but he failed. Even so, he has not lost his delight in the most sprite-like of waders. In this article he recalls some of his many muddy hours spent chasing after stints, and keys you into their forms and first autumn plumages.

EVERY YEAR – about August 21 – I get restless and feel strongly that I should be hunting stints again. This is because in the 1970s I spent hundreds of hours trying to sort out all seven species and was also committed to the hope of putting the dreaded Red-necked from far East Siberia onto the British List.

Over 15 years (and at least three strained human relationships!) later, the best identification texts have come from other pens than mine. Furthermore, it looks as if the honour of the first Red-necked will go to Andrew Grieve of Blacktoft Sands fame. Never mind; at the very least, I stirred the pot and my memories of some splendid wee birds will never fade.

Up to 1973, we all assumed that the British and Irish Stint list would contain only three American “Sandpipers” – Western, Semipalmated and Least – and two West Eurasian Stints – Little and

Temminck’s. In general, we expected Littles on demand every autumn, a Temminck's each late spring and, if we got lucky in the south-west of Ireland, one or other of the Yanks now and again.

The relative calm of this situation ended suddenly on September 24, 1973, when a “Semipalmated” a at Minsmere was trapped, found not to have toe webs and divided hopelessly into a somewhat mouldy “adult Little” or an equally tatty “adult Red-necked”.

This is only “much ado about Little”, wrote Peter Grant in the Rarities Committee judgement, but I was not convinced, as hot on the heels of the Minsmere scruff had come also a really odd juvenile. This bird flew onto a high tide roost on the Upper Humber on September 14 and had me transfixed for six days.

Cold-looking, without bright mantle lines, with dull wing coverts, it refused to be “Little”, and as” Red-necked” it has eventually collected the support of the stint artist, Peter Hayman, the whole of the Yorkshire Records Committee and even, in the form of winces, some of its initial rejectors. I do not expect it to make the British List (too much human trauma for that now) but it remains a very important bird. With several others in the 1970s, it forced the lifting of our sights onto all the world's stints. They all played catalyst to the ensuing efforts that have been made to clarify stint identification and hence status.

All this means that stint identification is no easy trek for observers and worse still for judges. Until very recently, no paper or book really grasped the thistles in the problems but there are now two excellent references: Jonsson, L, and Grant, PJ, Identification of Stints and Peeps, British Birds, 77: 293-315, 1984, with splendidly large illustrations, and Marchant, J, Prater, A, and Hayman P, Shorebirds: an identification guide to waders of the world, Beckenham, 1986, with several illustrations of every plumage.

Both the above works are full of the most acute perceptions and I recommend them without reservation.

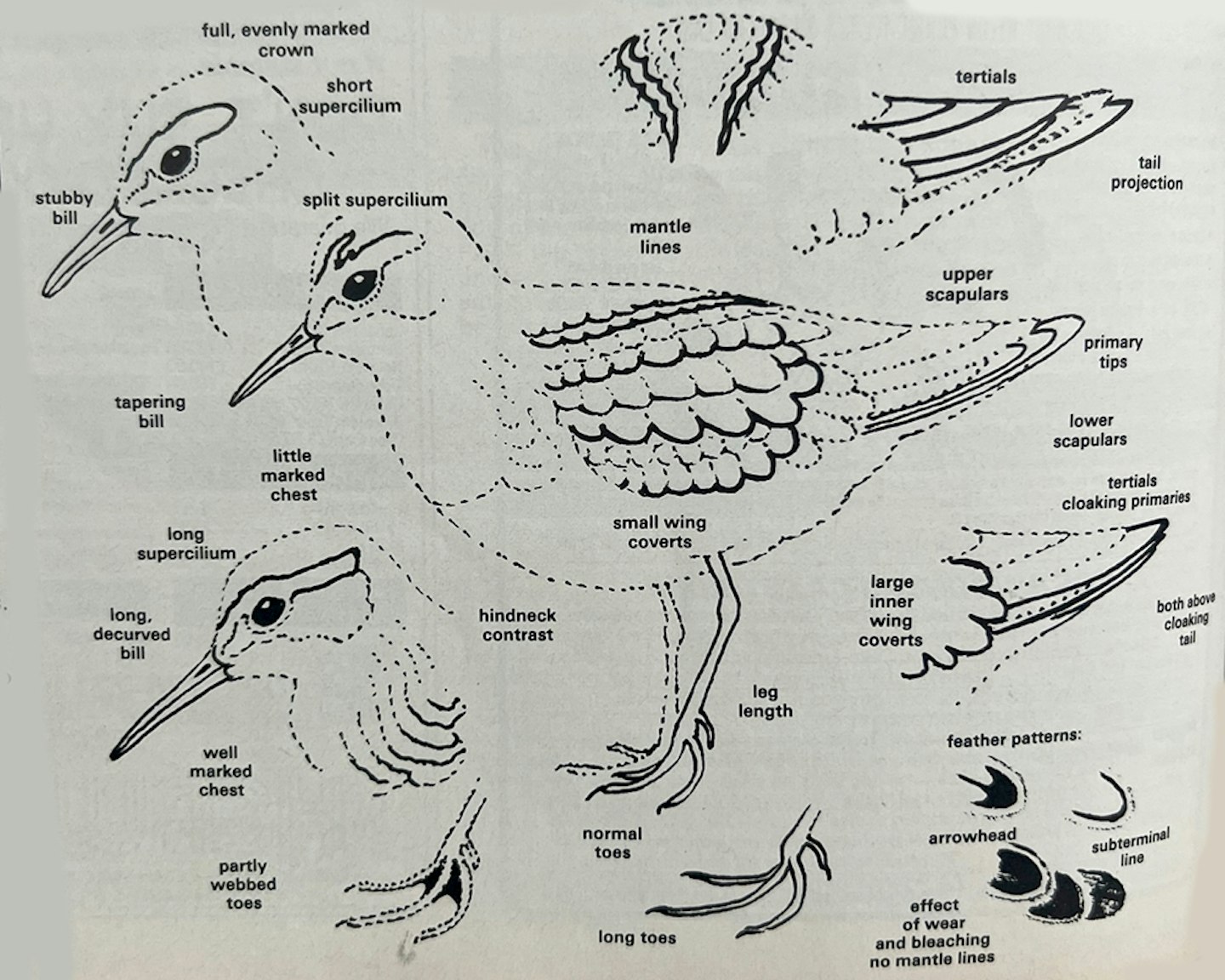

Unfortunately no book will get you close to stints, and close you must get if you are to have any chance of seeing the fine details that must now be confirmed for a certain claim to be made. There are three basic ploys in stint hunting.

1. Easy but subject to human crush; wait for birds to appear at a reserve; queue for place in hide; have bird pointed out; presumably get correct tick but learn nothing about stalking; occasionally scrub tick due to others’ mistake!

2. Not too difficult; pick reservoir with mud edge not far from East coast; visit regularly from mid-August, walking slowly round. Upwind, with light behind, learn to stalk stints (often amazingly tame, but other more timid waders lead them off); stare at them; possibly get tick but better rush back – with FULLEST POSSIBLE notes – to references, hoping that you have not missed the crucial character; if you have, go straight back and check it; confirm tick, feel proud!

3. Difficult but ultimate challenge; pick East coast estuary, with lagoon or soft, spring-tide-refreshed mud stretches below shoreline; find preferred areas and roosts; pick vantage points for telescope or learn to stalk stints in mud, without falling over or losing one or more boots: further acts as 2.

Now, the process of identification; I have to repeat that there is no easy route to stint identities. Even after Jonsson, Hayman and the others, some birds will remain unseparable or unjudged. The epitome of, and the key to, the group is Little. So, drown yourself in them, looking hard and long at not one, not 10, but 100.

In years of heavy trans-Eurasian flights, 100 Littles are not hard to find. Within them, you will see many immatures in juvenile to first-winter plumage, and a few adults in moult from summer to winter dress and also fully in the latter. In the young birds, you should spot a range of upper-part tones from buff (= fresh Semi-palmated) through foxey (= fresh Long-toed) to rich brown (= fresh Least) – and you must never fall for such temptations in mere plumage colour. The lasting stint characters are subtle; bare part structure and colours, back patterns, tertial length and like nuances have to be seen.

So, the first rule is LEARN LITTLE and get your eye in.

The second rule is ELIMINATE TEMMINCK'S. Happily, this is not difficult, because its long, rather short-legged form, cricket-like voice, habit of towering, drab plumage and above all white-edged tail add up to one really distinctive image in the group.

The third rule is BE PRIMED FOR THE RARE STINTS. They make up less than one per cent of all British stints but you might find one in your first 100 Littles. To get ready for them (and not blow your chances), you must be able to key into a series of character check-lists. Only if each sequence of checks ends up with the same name will you be entitled to consider a claim.

Even then, you must note every last feather on or other point about the bird if you are to prove it.

Feel challenged? Great, now invest in “Shorebirds”, and good luck with the Rarities Committee!

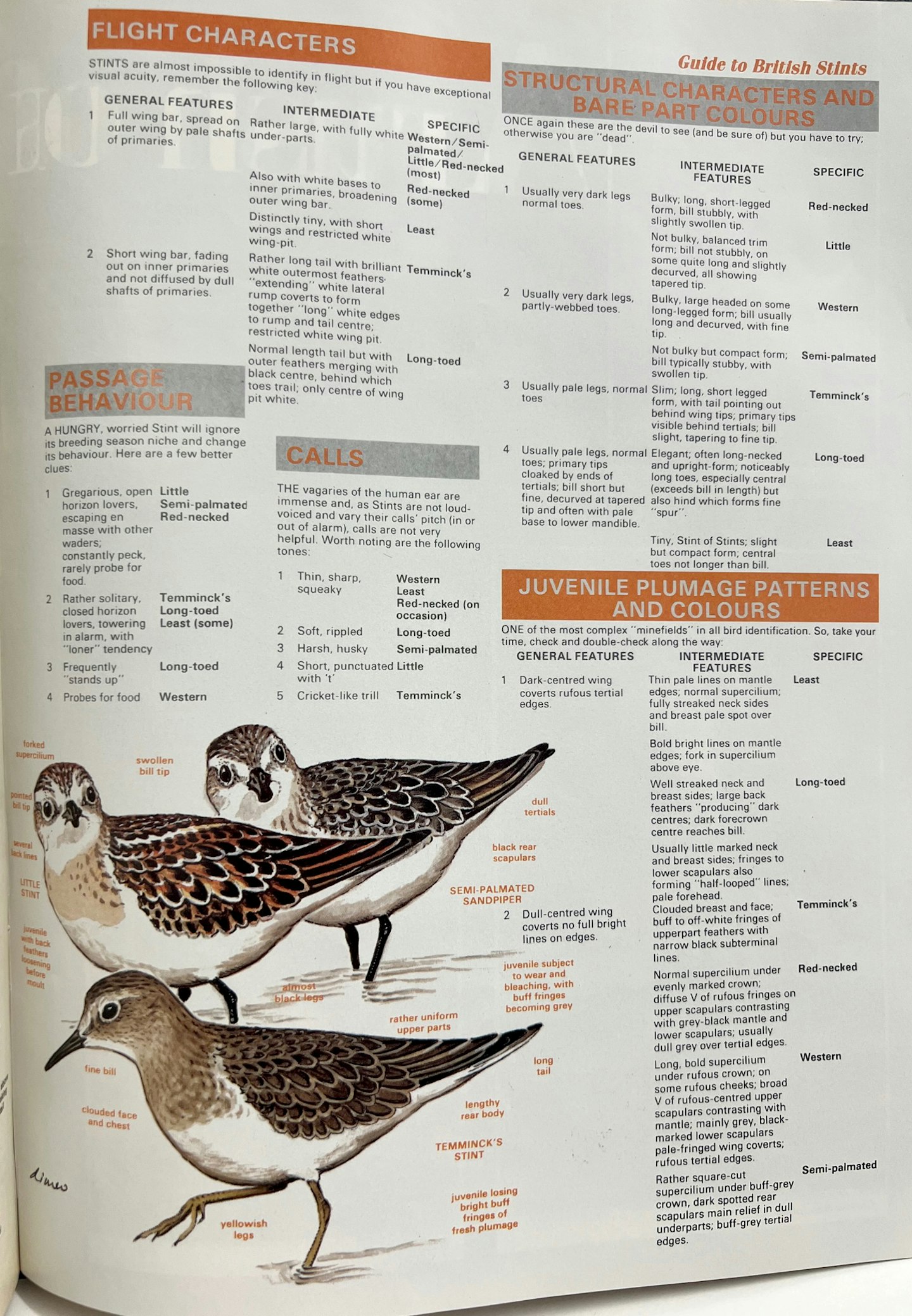

Guide to British Stints