Drifters from the east

August 1987

The 1950s concept of migrational drift has been much amended by later observations, but the theory and the commonest evidence for it the so-called ‘drift migrants’ have a lasting place in Britain ornithology. Here Ian Wallace discusses the great falls and the commonest passerines that appear out of bad weather and usually on easterly winds.

I was fortunate to have, as my fourth ornithological mentor, the late Kenneth Williamson. His winter presence in my school city of Edinburgh stimulated the young birdwatchers there hugely. Ken was our guru and we hung on his every word, dreaming of Fair Isle where he spent most of the year, not only finding rarities but also developing the work of the bird observatory to a full science. Ken was the first person to describe completely the phenomenon of drift.

My first observatory trip, to the Isle of May in the spring of 1949, was totally bereft of drift migrants. When at long last I set out for Fair Isle in September, 1951, the magic formula of ‘SE wind and fog’ greeted me at Orkney. Even so, there were only a few small birds in south Shetland and when finally I leapt ashore onto the magic isle, I was near desperate for a real drift. Happily, the weather mix held and soon the experts already at the observatory (nissen huts in those days!) led me through a classic drift arrival.

Among scores of small birds in the crops, the chief prizes were an immature Black-headed Bunting, which only I could clinch because its finder, the late Maury Meiklejohn, was not able (through colour blindness) to judge its full colour tones, and a Tawny Pipit which started out as a Short-toed Lark but was eventually clap-netted (in a space only 8 foot by 3!) by eight shepherding observers.

Late that night, Ken mused on his concept of drift and pronounced the day's evidence for first disorientation and then downwind flight to be indisputable. Who was I to disagree?

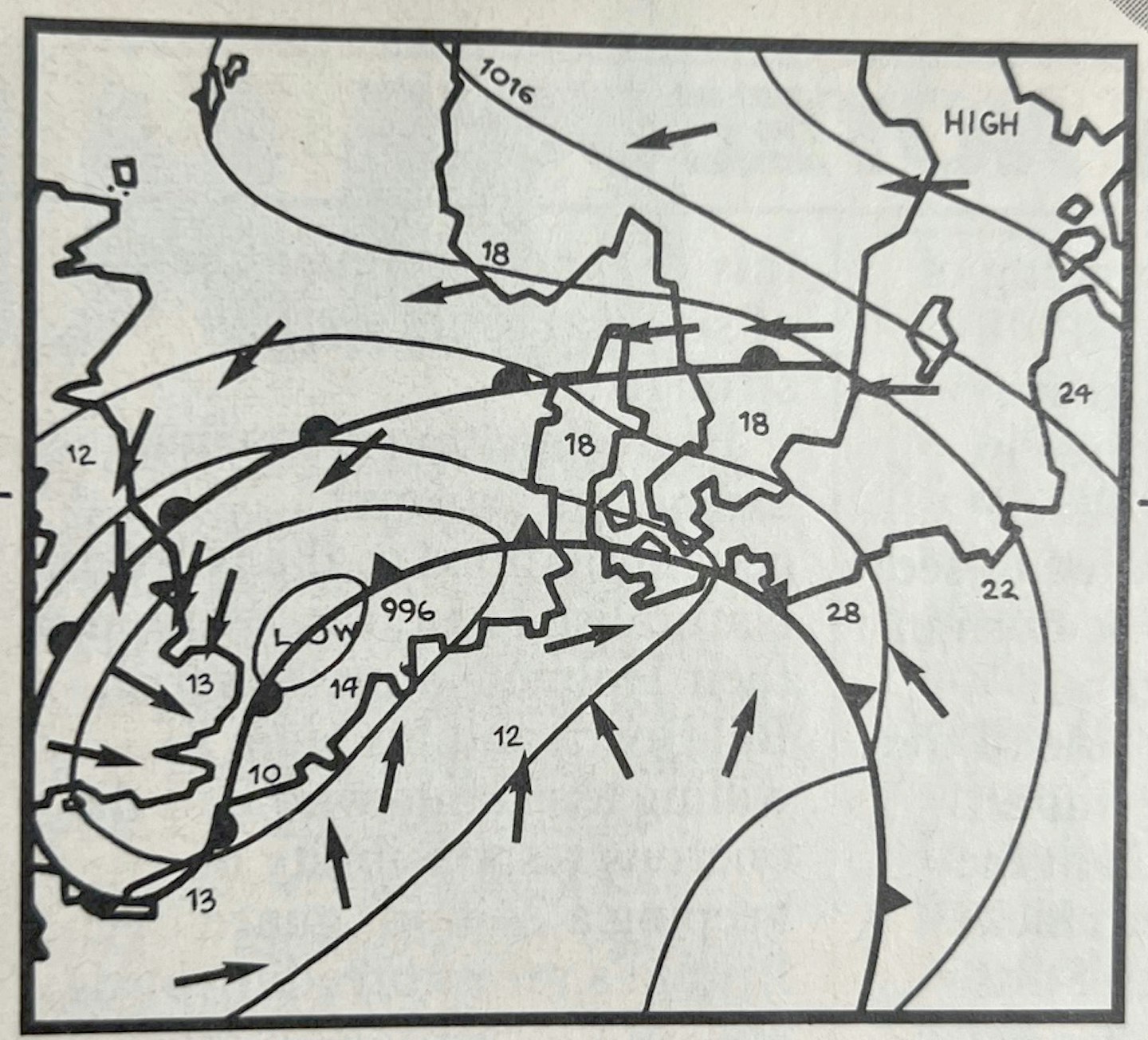

The approach vector of the huge drift of 3 Sept, 1965; weather over the North Sea and southern Fenno-Scandia at 1200 hours. From a warm anticyclone over the Baltic Sea, cooling easterlies blow across the North Sea, becoming northerlies along the East Coast. Fronts produce cloud cover from Yorkshire south and low temperatures in the Low Countries. Broad-front passage to the south turns west and becomes a pronounced drift. This is further focussed by tail winds along the east coast. Four-digit numbers indicate pressure; two digits temperature; arrows wind direction.

Thirty-six years later, drift and Fair Isle are no longer pre-eminent in British migration thought. Radar observations in the 1960s and growing experience of continental bird movements have rightly widened our perspective on migration, but the North Sea remains a veritable cockpit over which exceptional vagrancies and large drifts still occur.

As mentioned last month (July 1987’s BW) by Peter Clarke, one of the latter which affected much of the east coast on 3 September, 1965, broke every precedent even of Fair Isle. A huge, broad front passage left south Fenno-Scandia in fine weather on the 2nd; met easterlies and deep frontal cloud across Denmark and the southern North Sea and was finally headed west, to be deposited by a brief SE blow and cool rain.

Half a million birds rained down on 40km of Suffolk, and lesser but still record numbers fell on Norfolk, Lincolnshire and Yorkshire.

My seventh sense had taken me to Cley on the day and with some birds obvious 20 miles from the coast, I thought that I had begun and finished well – until too late in the afternoon to make Suffolk, I heard of the avalanche there, in which small bird numbers averaged 12 per metre!

In recent years, large drifts seem to have become rarer – or is it that we are all so rarity conscious, we just tear through them for the next tick? The best that I have experienced was a spring rush in Yorkshire on 1 May, 1978. It was, not a product of the traditional ‘SE and fog’ but a much more excruciating ‘NNE and very cold rain’.

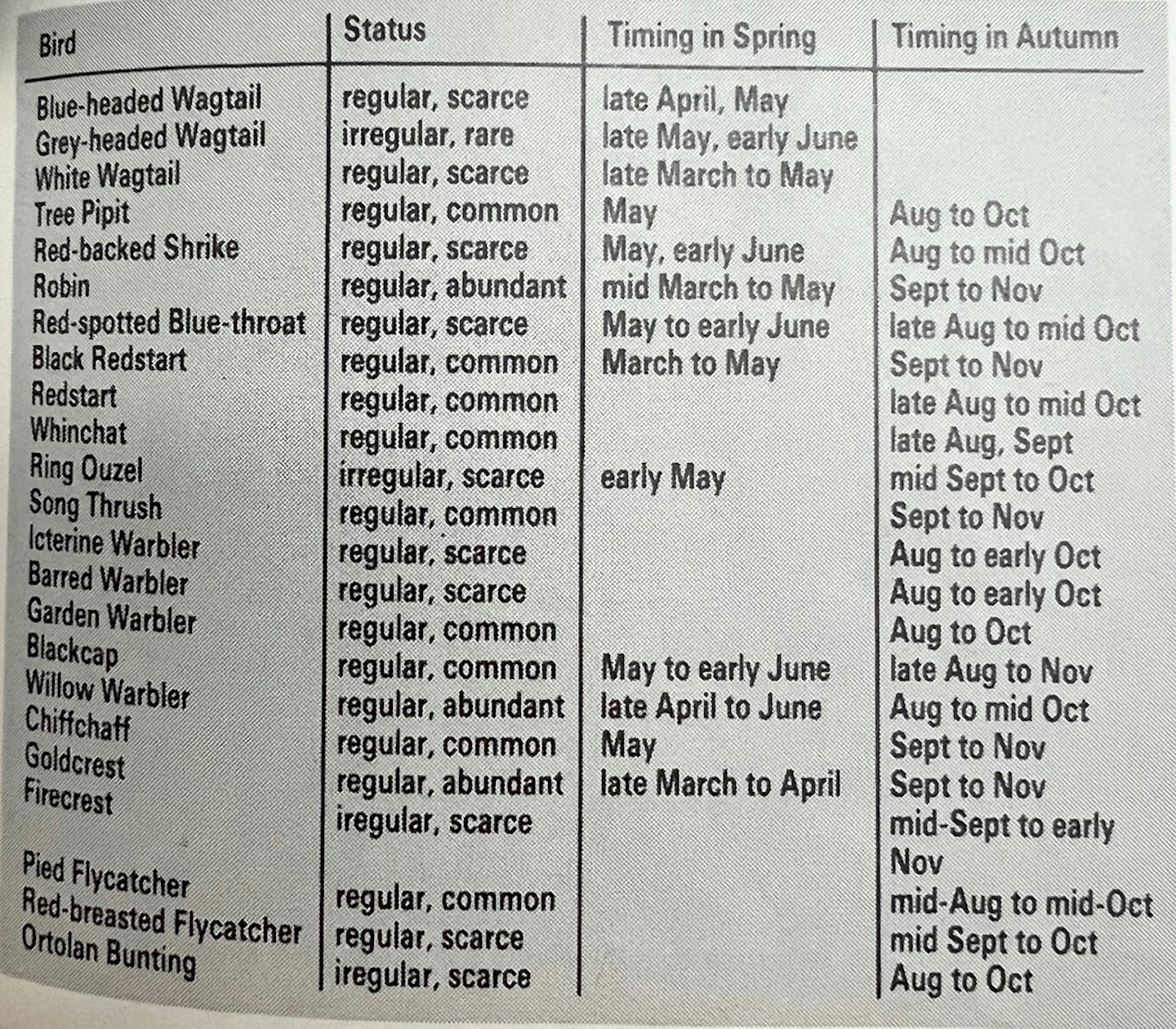

What has not changed is the typical species profile of drift migrants, displayed in the table below. Here I treat particularly the one shrike, four warblers (two in the guise of northern race) and two flycatchers.

Red-backed Shrike

Up to the 1950s, the 'butcher bird' could be found breeding quite widely on English heaths. Today, it appears almost exclusively in spring rashes and autumn drifts (or on re-directed passage after such events). So, to enjoy one, you will have to judge the right day for the east coast (and keep your fingers crossed). Often in spring, the majority of drifted Red-backs are males, but in autumn they are nearly all immatures. Hence the challenge of identification increases late in the year, for the odd Red-tailed, alias Isabelline, (and maybe even Brown) appear as vagrants. Usually shrikes perch conspicuously and give reasonable views. Spring males may also sing, giving out a strangely muted but often long-sustained jerky warble, which suggests a warbler unable to turn off its scratched record. Throughout the year, all birds commonly ‘chack’ in alarm or at disturbance; the note is double, recalling a chat but more rasping.

Pied Flycatcher

Although quite common as a breeding bird in western woods, the Pied Flycatcher is best known as an autumn drift migrant. It falls on northern isles and along the east and south coasts always signal much excitement in birdwatchers. ‘Piedy Flys’ make good markers for drifts and rarities. Well seen, they cannot be confused with Spotted or Red-breasted but even at at close range, not all birds in first autumn dress can be separated from the newly split Collared and Semicollared. So the Pied may be seen as just the commonest part of a complex super-species, not yet fully worked out in the field. Its constant wing and tail flicks and fairly quiet but emphatic calls assist its location

Northern Willow Warbler

The north-west continental populations of the Willow Warbler, the commonest summer visitor to the Palearctic, frequently drift to Britain. Their falls can be large. Unfortunately racial differences in the species are notoriously unstable and drift migrants wearing plumages like those of British breeding stock cannot be certainly named. So make sure that your attempt on northern birds are made in the right context – a full supporting cast of other drift migrants. When there are definitely a lot of pale, clean willows about, you can bet that they are northerners.

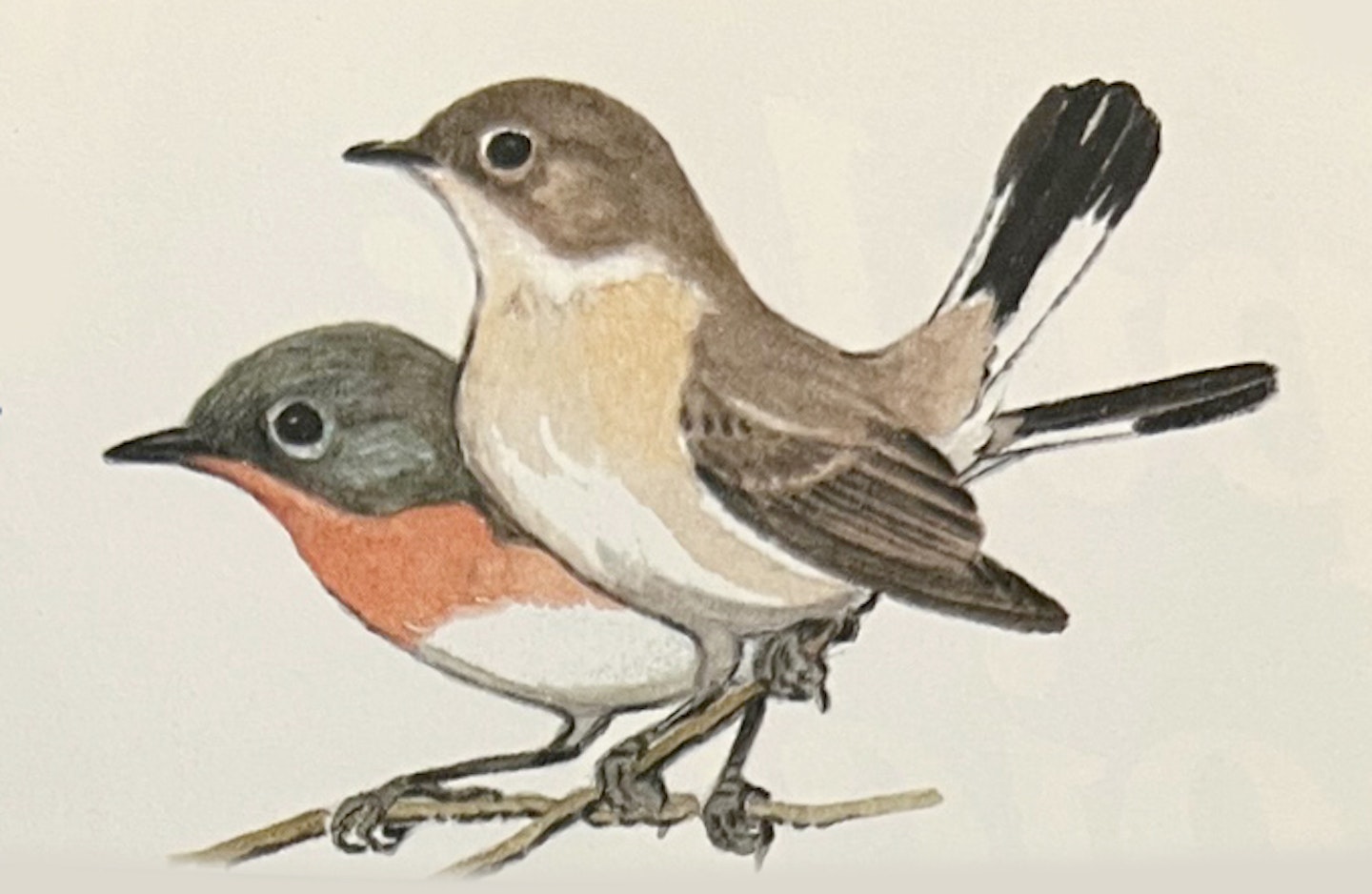

Red-breasted flycatcher

Like the Barred Warbler, the Red-breasted Flycatcher is as much (if not more) a reversed migrant than a drifter, but nevertheless it appears regularly in major falls. Small with a unique tail pattern (shades of male Red-backed Shrike), it is virtually unmistakable. Its tameness as a migrant is often marked. It calls like a dry-toned Redstart but quietly, being difficult to locate by ear. It flies the highest sallies of its family.

Icterine warbler

Up to the 1960s, the Hippolais warblers were not well known and subject to much confusion. Then and ever since, the Icterine has been the commonest. Its wide latitudinal range in Europe, reaching 67°N in Fenno-Scandia, provokes frequent appearances on the East and South coasts. It is, with the next species, the easiest ‘foreign’ warbler to find, but once again there is a risk of confusion with close relatives, especially the Melodious. Adults occur on both migrations and young in autumn, The Icterine calls like a loud Garden Warbler; occasionally, a spring migrant male will sing in vehement, musical outbursts.

Barred Warbler

Since the 19th Century, this big Sylvia warbler has been the most frequent of the scarcer drift migrants. In September, 1935, there was a fall of 40 on Fair Isle alone. In recent years, it has become less numerous but it remains the first foreign warbler usually to cross a migrant watcher’s path. It occurs widely in our lands with reversed migration as well as drift taking it to normally barren places like Cape Wrath and the Aran Isles. At a distance or in a glimpse, this strongly-built, full-tailed warbler is always a puzzle –suggesting several other large vagrant species – but close to, its strong bill and dull but distinct wing bars show in all plumages. Only adults are barred or, more correctly, scalloped below.

Scandinavian Chiffchaff

The north European communities of this bird also touch Britain through drift but their presences are usually less marked than those of the willow warbler. The separation of Scandinavian from southern birds is easiest in spring adults and first autumn birds. Look for yours in the context of early and late drifts, with Blackcaps and Reed Buntings as markers. Some Scandinavian Chiffchaffs cheep like chicks. Siberian birds also reach our lands as reversed migrants. Their appearance is even paler and cleaner that of typical Scandinavian birds. Altogether, the northern and eastern races make southern Chiffchaffs look swarthy!

Captions