Charming Chats

April 1987

Ask birdwatchers for their favourite birds and waders, warblers (and, of course, rarities) will probably be top of the poll but for real charm and many puzzles. Chats come first for Ian Wallace

Sandwiched systematically between the accentors and the thrushes, the chats make up a distinct group of fairly small, sprightly, fast-flying passerines that exploit mostly ground cover. A total of 19 species are on the British and Irish list but in this article, I deal only with the eight breeding or regular migrant species. Don't be depressed by this restriction: we shall come back to the rare ones, and even the common birds have their mysteries. No chat presents a simple target. So you must learn the common ones first.

The epitome of the chat tribe is the Robin. Except in Shetland and bits of the Hebrides and Orkney, it gets everywhere and has become so confiding around human habitation that in Britain it has been honoured as the national bird. Lowland gardens, parks and field thickets are not the Robin's natural habitat, however, and the events that led it down from its ancestral home of high forest to its modern universe are puzzling.

The theory is that centuries of coppicing – the periodic cropping and patchy re-growth of woods – allowed it into all-forested areas and that from those it adapted further to exploit any ‘treed’ or bushy cover. Abroad, Robins can be hard to find (e.g. above 2,000 metres in the Canary Islands) but in many English woods they frequently dominate all other passerines. The British population was estimated in 1968-72 at five million pairs. Certainly, the Robin is one of a handful of really common birds.

The Robin is also a great character, with its apparently meek tameness outside back doors in winter hiding a complex personality. Both sexes defend territories in autumn and early winter (to the point of real fights over food sources), sing (males in every month except July) and migrate from the northern parts of their range (or exceptionally cold weather). The last behaviour can make nonsense of claims like "our Robin has been with us for years"; it is probably a series of red-breasted adventurers!

To get your eye in, the Robin as our commonest chat deserves frequent study. Its fast, flitting and ducking, sometimes tail-twitching flight, its pounce down or dart forward onto prey, its bouncy hop and its nervous bowing and bobbing are all shared by relatives. So, every Robin image helps build your perception of the tribe, giving you a better chance to avoid confusing its members with the larger warblers, accentors and other small songbirds. Preparing your perception is very important as the really rare chats (bar the Wheatears) will only exceptionally present you with a gift view. Chat-hunting is all about brief glimpses and prayers for re-appearances!

Open country chats

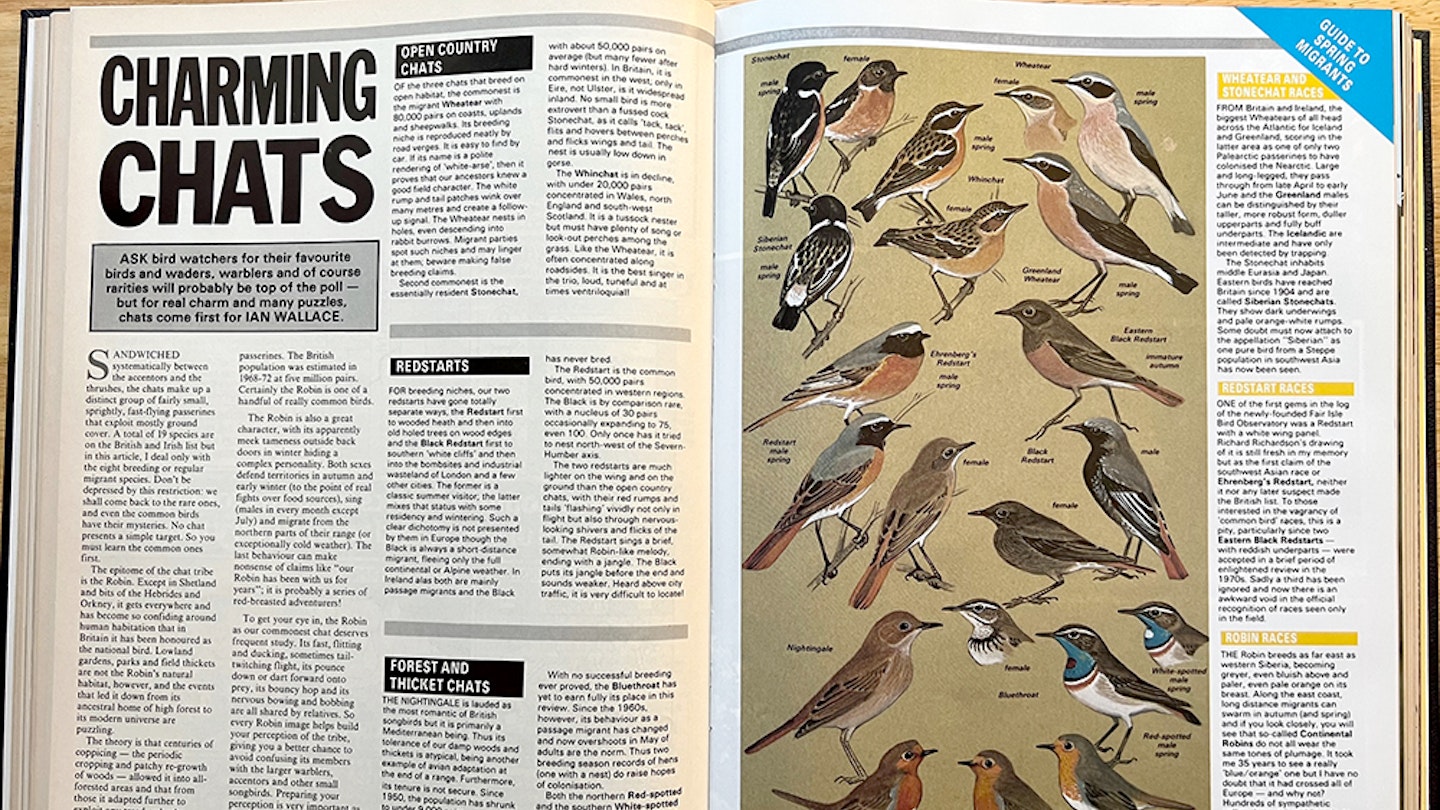

Of the three chats that breed on open habitat, the commonest is the migrant Wheatear with 80,000 pairs on coasts, uplands and sheepwalks. Its breeding niche is reproduced neatly by road verges. It is easy to find by car. If its name is a polite rendering of 'white-arse' then it proves that our ancestors knew a good field character. The white rump and tail patches wink over many metres and create a follow- up signal. The Wheatear nests in holes, even descending into rabbit burrows. Migrant parties spot such niches and may linger at them; beware making false breeding claims.

Second commonest is the essentially resident Stonechat, with about 50,000 pairs on average (but many fewer after hard winters). In Britain, it is commonest in the west; only in Eire, not Ulster, is it widespread inland. No small bird is more extrovert than a fussed cock Stonechat, as it calls 'tack, tack' flits and hovers between perches and flicks wings and tail. The nest is usually low down in gorse.

The Whinchat is in decline, with under 20,000 pairs concentrated in Wales, north England and south-west Scotland. It is a tussock nester but must have plenty of song or look-out perches among the grass. Like the Wheatear, it is often concentrated along roadsides. It is the best singer in the trio, loud, tuneful and at times ventriloquial!

Redstarts

For breeding niches, our two redstarts have gone totally separate ways, the Redstart first to wooded heath and then into old holed trees on wood edges and the Black Redstart first to southern 'white cliffs' and then into the bombsites and industrial wasteland of London and a few other cities. The former is a classic summer visitor; the latter mixes that status with some residency and wintering.

Such a clear dichotomy is not presented by them in Europe though the Black is always a short-distance migrant, fleeing only the full continental or Alpine weather. In Ireland alas both are mainly passage migrants and the Black has never bred.

The Redstart is the common bird, with 50,000 pairs concentrated in western regions. The Black is by comparison rare, with a nucleus of 30 pairs occasionally expanding to 75, even 100. Only once has it tried to nest north-west of the Severn- Humber axis. The two redstarts are much lighter on the wing and on the ground than the open country chats, with their red rumps and tails "flashing vividly not only in flight but also through nervous- looking shivers and flicks of the tail.

The Redstart sings a brief, somewhat Robin-like melody, ending with a jangle. The Black puts its jangle before the end and sounds weaker. Heard above city traffic, it is very difficult to locate!

Forest and thicket chats

The Nightingale is lauded as the most romantic of British songbirds but it is primarily a Mediterranean being. Thus its tolerance of our damp woods and thickets is atypical, being another example of avian adaptation at the end of a range. Furthermore, its tenure is not secure. Since 1950, the population has shrunk to under 9,000 pairs.

The males sing most at dusk and so that is your best time to listen out. In Europe, Nightingales frequently perch and feed in the open but in England, they are shy and the trills and crescendos usually pour out of dense cover.

With no successful breeding ever proved, the Bluethroat has yet to earn fully its place in this review. Since the 1960s, however, its behaviour as a passage migrant has changed and now overshoots in May of adults are the norm. Thus two breeding season records of hens (one with a nest) do raise hopes of colonisation. Both the northern Red-spotted and the southern White-spotted races breed respectively only the North Sea and the English Channel away. The song of the Bluethroat is loud and in some phrases Nightingale-like; it differs in being sweeter and more varied and in being often uttered in a pipit-like song flight.

Wheatear and Stonechat races

Wheatear and Stonechat races from Britain and Ireland, the biggest Wheatears of all head across the Atlantic for Iceland and Greenland, scoring in the latter area as one of only two Palearctic passerines to have colonised the Nearctic. Large and long-legged, they pass through from late April to early June and the Greenland males can be distinguished by their taller, more robust form, duller upperparts and fully buff underparts. The Icelandic are intermediate and have only been detected by trapping. The Stonechat inhabits middle Eurasia and Japan. Eastern birds have reached Britain since 1904 and are called Siberian Stonechats. They show dark underwings and pale orange-white rumps. Some doubt must now attach to the appellation "Siberian” as one pure bird from a Steppe population in south-west Asia has now been seen.

Redstart races

One of the first gems in the log of the newly-founded Fair Isle Bird Observatory was a Redstart with a white wing panel Richard Richardson's drawing of it is still fresh in my memory but as the first claim of the southwest Asian race or Ehrenberg's Redstart, neither it nor any later suspect made the British list. To those interested in the vagrancy of 'common bird' races, this is a pity, particularly since two Eastern Black Redstarts with reddish underparts were accepted in a brief period of enlightened review in the 1970s. Sadly, a third has been ignored and now there is an awkward void in the official recognition of races seen only in the field.

Robin races

The Robin breeds as far east as western Siberia, becoming greyer, even bluish above and paler, even pale orange on its breast. Along the east coast, long distance migrants can swarm in autumn (and spring) and if you look closely, you will see that so-called continental Robins do not all wear the same tones of plumage. It took me 35 years to see a really 'blue/orange' one but I have no doubt that it had crossed all of Europe and why not? Hundreds of sympatric Yellow-browed Warblers do so every year. Do not however rush your attempt at European and Russian birds. Our own race can be weakly coloured in first winter.

2020s update

Chat breeding populations

The most recent estimate of the Robin’s UK breeding population is 6.7 million pairs

Wheatears are up to 240,000 breeding pairs

Stonechats are slightly up to 59,000 breeding pairs

Whinchats are up to 47,000 breeding pairs

Redstarts have doubled in population (or at least in counted birds) to 100,000 pairs

About 20-45 pairs of Black Redstart breed in the UK, these days

Nightingale populations have shrunk still further to about 6,700 pairs in the UK

Siberian Stonechat is now considered a separate species from Stonechat, and has been split further so there is a third species, Stejgneger’s Stonechat recognised on The British List. A potential further split of Siberian Stonechat could see the Caspian Stonechat (which has a Wheatear-like tail end) recognised as another British bird (having occurred here at least seven times).

A single Moussier’s Redstart (a male) has been recorded in the UK, T Dinas Head, Pembrokeshire on 24 April 1988.