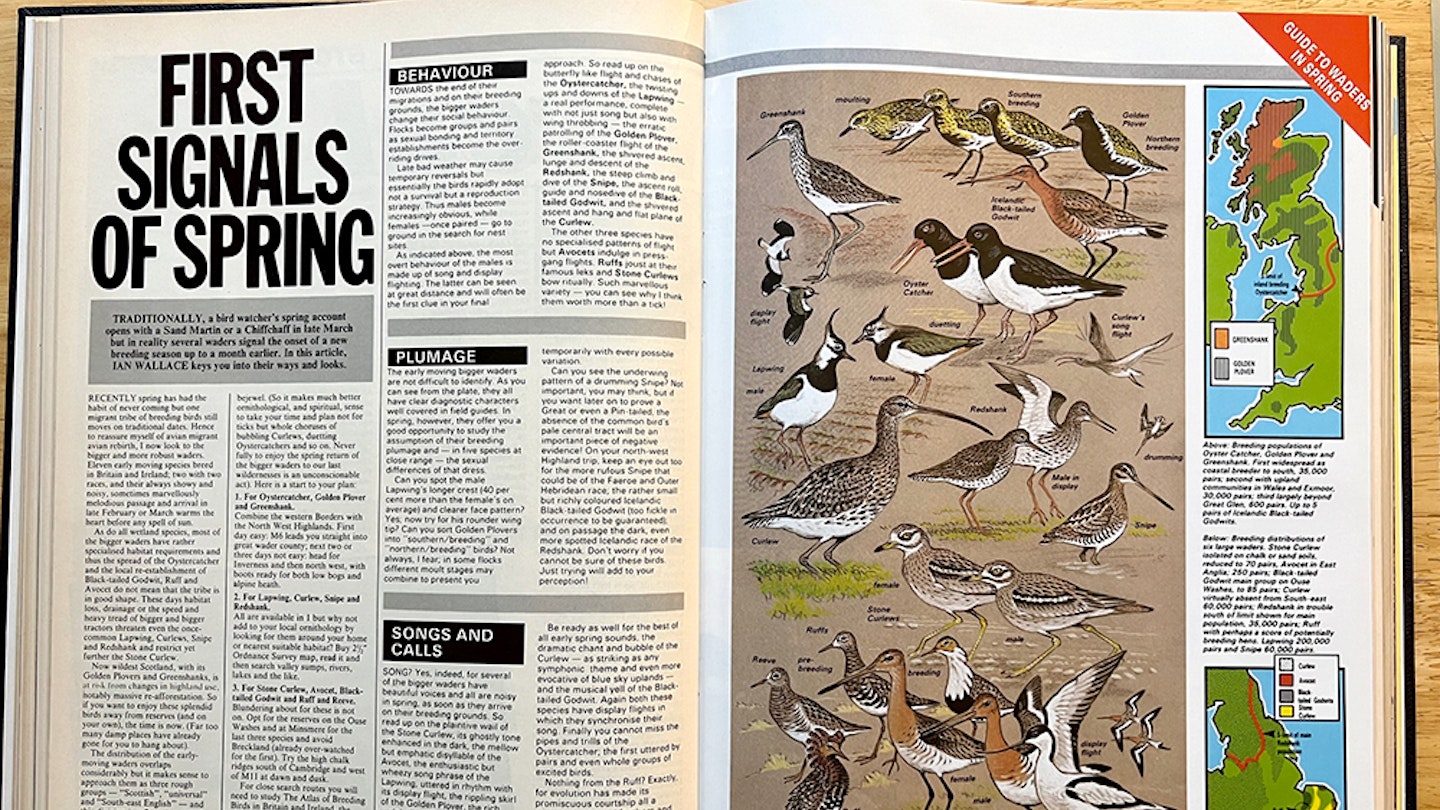

FIRST SIGNALS OF SPRING

March 1987

Traditionally, a birdwatcher's spring account opens with a Sand Martin or a Chiffchaff in late March, but in reality, several waders signal the onset of a new breeding season up to a month earlier, In this article Iand Wallace keys you into their ways and looks.

Recently, spring has had the habit of never coming, but one migrant tribe of breeding birds still moves on traditional dates. Hence, to reassure myself of avian migrant avian rebirth, I now look to the bigger and more robust waders. Eleven early moving species breed in Britain and Ireland; two with two races, and their always showy and noisy, sometimes marvellously melodious passage and arrival in late February or March warms the heart before any spell of sun.

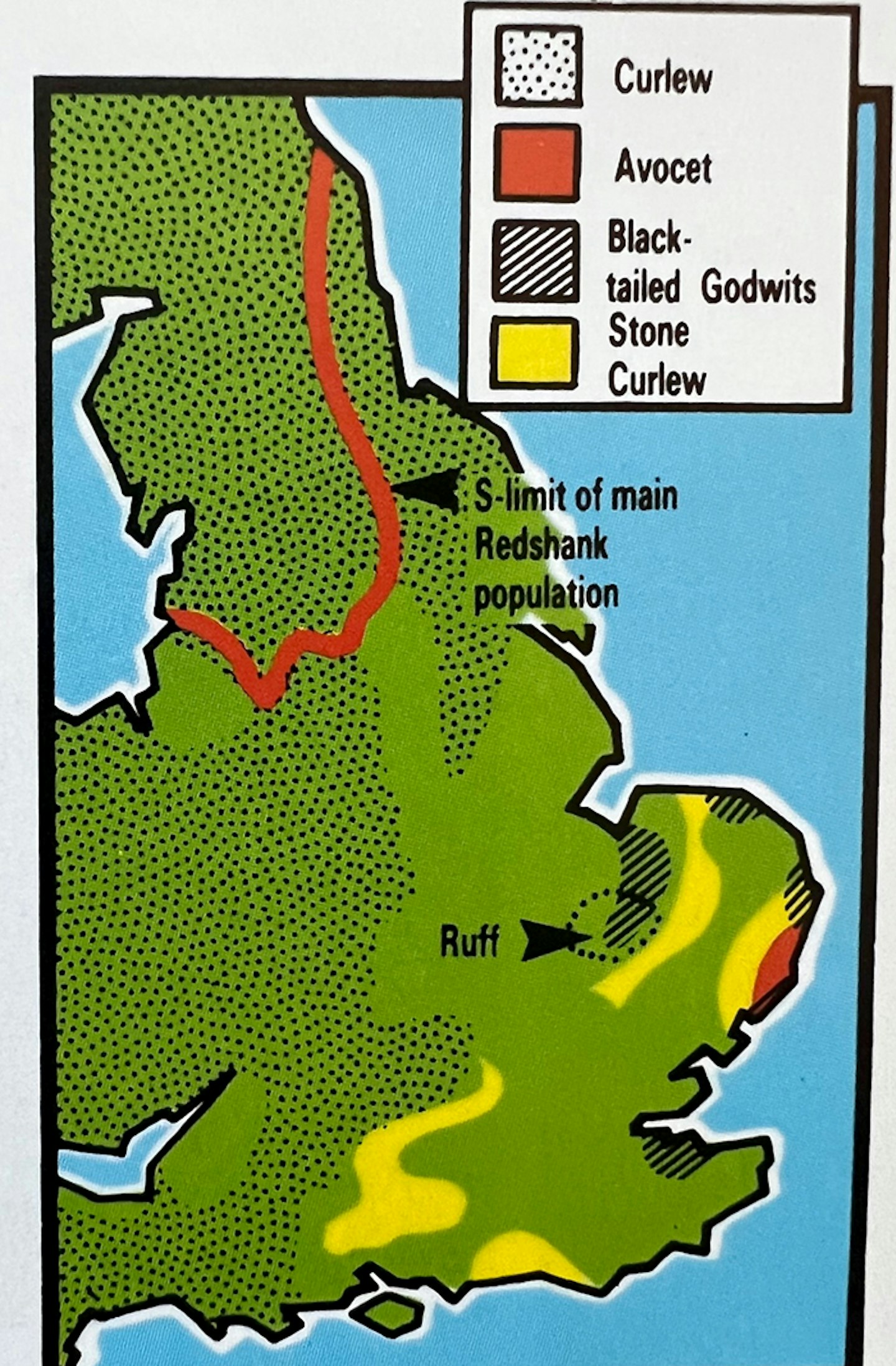

As do all wetland species, most of the bigger waders have rather specialised habitat requirements and thus the spread of the Oystercatcher and the local re-establishment of Black-tailed Godwit, Ruff and Avocet do not mean that the tribe is in good shape. These days, habitat loss, drainage or the speed and heavy tread of bigger and bigger tractors threaten even the once-common Lapwing, Curlews, Snipe and Redshank and restrict yet further the Stone-curlew.

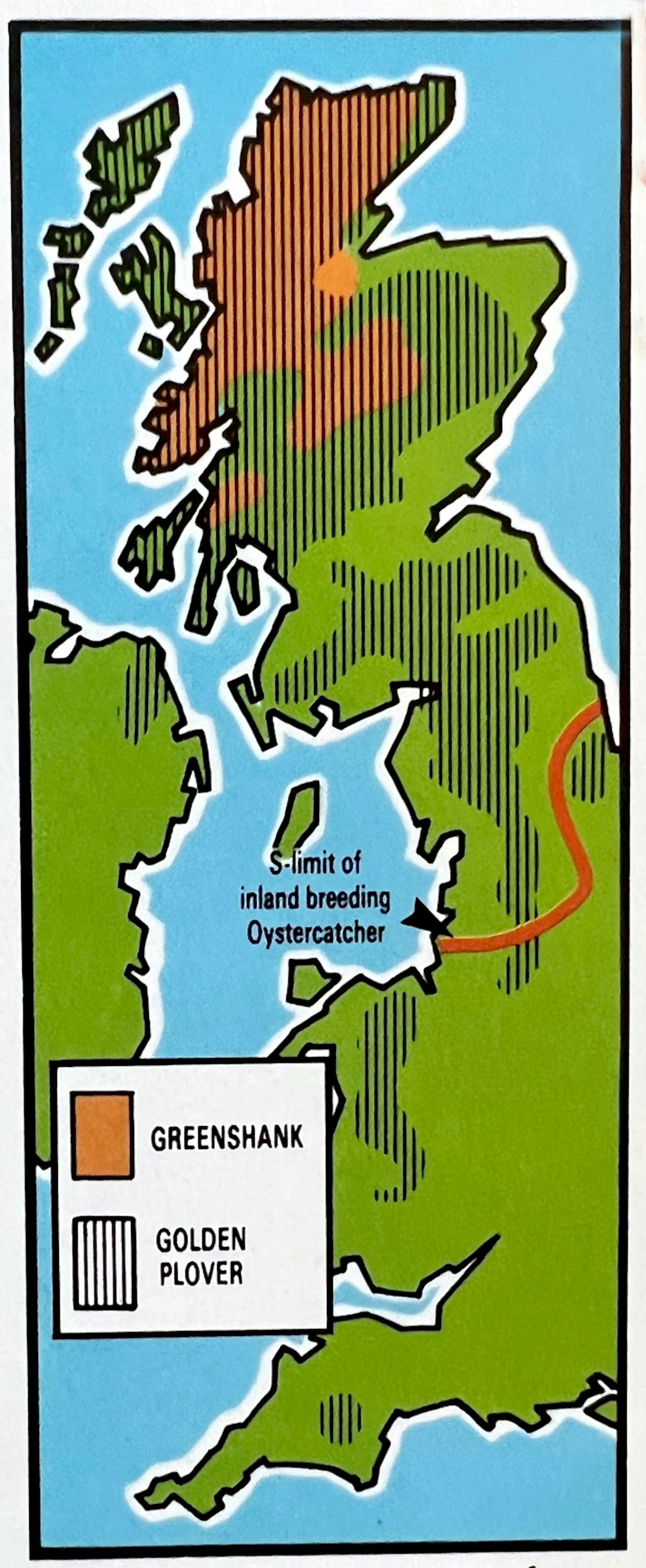

Now, wildest Scotland, with its Golden Plovers and Greenshanks, is at risk from changes in highland use, notably massive re-afforestation. So if you want to enjoy these splendid birds away from reserves (and on your own), the time is now. (Far too many damp places have already gone for you to hang about).

The distribution of the early-moving waders overlaps considerably but it makes sense to approach them as three rough groups: ‘Scottish’, ‘Universal’ and ‘South-east English’ and this division is reflected in the grouping of the plate subjects and the maps.

How do you set sail? For a start, forget a quick twitch. If you want to understand the birds as beings, you should savour their sight and sound and do so against high mountains, ancient flows, Caledonian forest and the magic places that waders bejewel. (So it makes much better ornithological, and spiritual sense to take your time and plan not for ticks but whole choruses of bubbling Curlews, duetting Oystercatchers and so on. Never fully to enjoy the spring return of the bigger waders to our last wildernesses is an unconscionable act).

Here is a start to your plan:

1. For Oystercatcher, Golden Plover and Greenshank.

Combine the western Borders with the North West Highlands. First day easy: M6 leads you straight into great wader county; next two or three days not easy: head for Inverness and then north west, with boots ready for both low bogs and alpine heath.

2. For Lapwing, Curlew, Snipe and Redshank.

All are available in 1 but why not add to your local ornithology by looking for them around your home or nearest suitable habitat? Buy 2½’ Ordnance Survey map, read it and then search valley sumps, rIvers, lakes and the like.

3. For Stone-curlew, Avocet, Black-tailed Godwit and Ruff (and Reeve).

Blundering about for these is not on. Opt for the reserves on the Ouse Washes and at Minsmere for the last three species and avoid Breckland (already over-watched for the first). Try the high chalk ridges south of Cambridge and west of M11 at dawn and dusk.

For close search routes you will need to study The Atlas of Breeding Birds in Britain and Ireland, the Scottish Bird Report and reserve news from the RSPB and the Wildfowl Trust. A bit of a chore? Yes, but birds are best when you hunt them, not just collect them, and you will learn to judge habitat, spot quiet places and perceive all sorts of things that will contribute to your personal skills as a bird watcher.

BEHAVIOUR

Towards the end of their migrations and on their breeding grounds, the bigger waders change their social behaviour. Flocks become groups and pairs as sexual bonding and territory establishments become the over- riding drives.

Late bad weather may cause temporary reversals but essentially the birds rapidly adopt not a survival but a reproduction strategy. Thus males become increasingly obvious, while females -once paired go to ground in the search for nest sites.

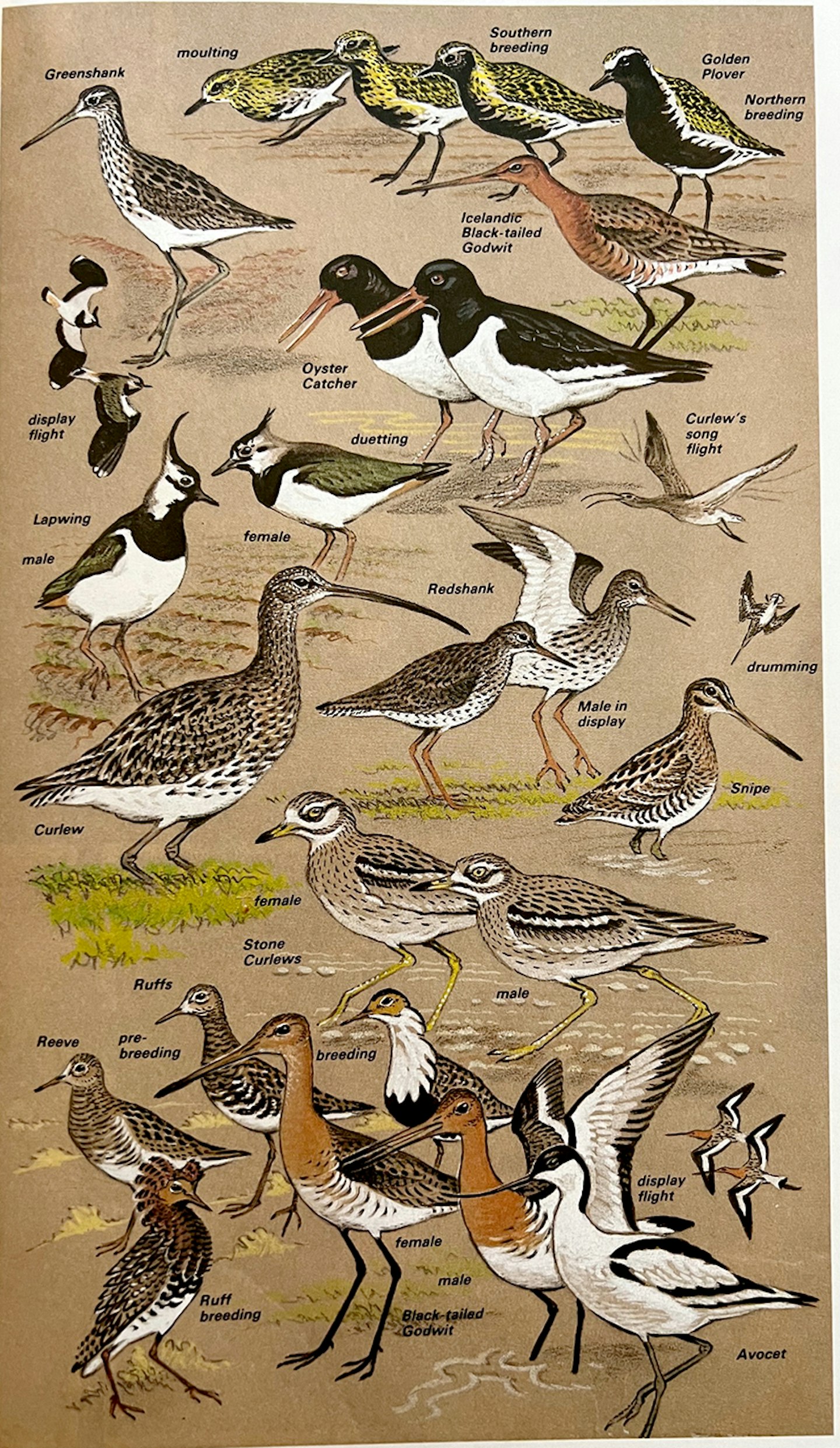

As indicated above, the most overt behaviour of the males is made up of song and display flighting. The latter can be seen at great distance and will often be the first clue in your final approach. So read up on the butterfly like flight and chases of the Oystercatcher, the twisting ups and downs of the Lapwing a real performance, complete with not just song but also with wing throbbing the erratic patrolling of the Golden Plover, the roller-coaster flight of the Greenshank, the shivered ascent, lunge and descent of the Redshank, the steep climb and dive of the Snipe, the ascent roll, quide and nosedive of the Black- tailed Godwit, and the shivered ascent and hang and flat plane of the Curlew.

The other three species have no specialised patterns of flight but Avocets indulge in press gang flights. Ruffs joust at their famous leks and Stone-curlews bow ritually. Such marvellous variety you can see why I think them worth more than a tick!

PLUMAGE

The early moving bigger waders are not difficult to identify. As you can see from the plate, they all have clear diagnostic characters well covered in field guides. In spring, however, they offer you a good opportunity to study the assumption of their breeding plumage and in five species at close range the sexual differences of that dress.

Can you spot the male Lapwing's longer crest (40% more than the female's on average) and clearer face pattern? Yes; now try for his rounder wing tip? Can you sort Golden Plovers into 'southern/breeding and 'northern/breeding birds? Not always, I fear; in some flocks different moult stages may combine to present you temporarily with every possible variation.

Can you see the underwing pattern of a drumming Snipe? Not important, you may think, but if vou want later on to prove a Great or even a Pin-tailed, the absence of the common bird's pale central tract will be an important piece of negative evidence! On your north-west Highland trip, keep an eye out too for the more rufous Snipe that could be of the Faeroe and Outer Hebridean race; the rather small but richly coloured Icelandic Black-tailed Godwit (too fickle in occurrence to be guaranteed); and on passage the dark, even more spotted Icelandic race of the Redshank. Don't worry if you cannot be sure of these birds. Just trying will add to your perception!

SONGS AND CALLS SONG?

Yes, indeed, for several of the bigger waders have beautiful voices and all are noisy in spring, as soon as they arrive on their breeding grounds. So read up on the plaintive wail of the Stone-curlew, its ghostly tone enhanced in the dark, the mellow but emphatic disyllable of the Avocet, the enthusiastic but wheezy song phrase of the Lapwing, uttered in rhythm with its display flight, the rippling skirl of the Golden Plover, the rich yodel of the Greenshank, the titter and triplets of the Redshank again synchronised with a display flight, and the persistent chipping of the Snipe actually voiced, unlike the instrumental movement of outer tail feathers which produces the drumming.

Be ready as well for the best of all early spring sounds, the dramatic chant and bubble of the Curlew as striking as any symphonic theme and even more evocative of blue sky uplands and the musical yell of the Black- tailed Godwit. Again both these species have display flights in which they synchronise their song. Finally you cannot miss the pipes and trills of the Oystercatcher; the first uttered by pairs and even whole groups of excited birds.

Nothing from the Ruff? Exactly, for evolution has made its promiscuous courtship all a matter of coloured feathers and posturing (and then not until May).

For calls, see your field guide which will give the commonest. Take particular care with the two ‘shanks’ notes and then you will be able to pick them up at great distance.

Breeding populations of Oyster Catcher, Golden Plover and Greenshank. First widespread as coastal breeder to south, 35,000 pairs; second with upland communities in Wales and Exmoor, 30,000 pairs; third largely beyond Great Glen, 600 pairs. Up to 5 pairs of Icelandic Black-tailed Godwits.

Breeding distributions of six large waders. Stone-curlew isolated on chalk or sand soils, reduced to 70 pairs; Avocet in East Anglia, 250 pairs; Black-tailed Godwit main group on Ouse Washes, to 85 pairs; Curlew virtually absent from South-east 60,000 pairs; Redshank in trouble south of limit shown for main population, 35,000 pairs; Ruff with perhaps a score of potentially breeding hens. Lapwing 200,000 pairs and Snipe 60,000 pairs.

2020s update

Just about the only surviving regular breeding ground for Black-tailed Godwits (of the lanky European subspecies, Limosa limosa limosa) is now the Nene Washes, east of Peterborough, Cambridgeshire. On the RSPB managed land, there are about 20 breeding pairs. Attempts to recolonise the Ouse Washes have been made in recent years, in a ‘headstartin’ scheme, by removing the first laid eggs from the Nene Washes to rear the young in captivity prior to release at the Ouse Washes.

There are now up to 400 pairs of Stone-curlews breeding in the UK, mostly in the brecklands of Norfolk and Suffolk and in Wiltshire at Salisbury Plain.

Also promising is the rise of Avocet populations to some 1,500 breeding pairs!

Curlew populations have declined recently, but still remain at 66,000 pairs.

There are now just 25,000 pairs of Redshanks, while Ruff are just about extinct as breeders. Lapwing numbers have crashed to 144,000 breeding pairs but Snipe estimates are at about 80,000 breeding pairs.

These days what used to be considered the American subspecies of Snipe is now recognised as a full species: Wilson’s Snipe. So check any Snipe carefully…