An eye for plumage - part 1

January 1987

Gulls used not to be favourite targets for birdwatchers but with recent advances in their identification and in the observed numbers of vagrants – the whole tribe is now much watched. In the first of two articles, Ian Wallace discusses the bigger ones.

Born into the east coast Herring industry, the long calls of Shetland Herring Gulls were the first bird sounds that I heard. However raucous, the yells of large gulls still turn my head, and their increasing success and ubiquity mean that even central English skies are rare without them.

Large gulls set birdwatchers some intriguing puzzles in behaviour, and specific and subspecific, characters. The latter are hugely embarrassed by several years' complexities in immature plumage (and its wear). So, most large gulls may seem brutish, but your task in separating them requires a keen eye, a good memory and some finely tuned knowledge.

How do you build up your gull guide? Firstly, you study the modern texts on them. I recommend three – Peter Grant's Gulls: A guide to identification (1986) with many excellent photographs but little general characterisation; Peter Harrison's Seabirds (1986), with good to very good colour plates and more characterisation; and The Birds of the Western Palearctic Vol (1983), with poor flight plates and confused systematics but even more characterisation. They should prime the pump of knowledge.

Secondly, you find a lot of large gulls at a roost or rubbish tip that you can get close to and learn their settled and close-flight appearance. Thirdly, you pick out a flight line to a roost and study their more distant flight characters and actions. (Sounds like hard work but it has to be. Muck about and you will make mistakes).

The ‘official list’ of the bigger gulls is nine-long with four breeding species in order of population size, Herring (350,000 plus pairs), Lesser Black-backed (50,000 plus pairs), Common (50,000 pairs) and Great Black-backed (25,000 plus pairs) – and next two winter visitors – Glaucous (about 500 per annum) and Iceland (about 100 per annum) and then the increasingly obvious Ring-billed (100 in 1985) and last a rare pair Ivory (80 in total) and Great Black-headed (6 only).

In my view, your ‘working list’ ought to have at least two more on it – Thayer's and Audouin's – and don't forget the four northern and at least one southern races of Herring, three of lesser Black-backed, two of Iceland and two of Common that visit Britain and Ireland, Whoever said that gulls were boring? The truth is that they are mind-boggling!

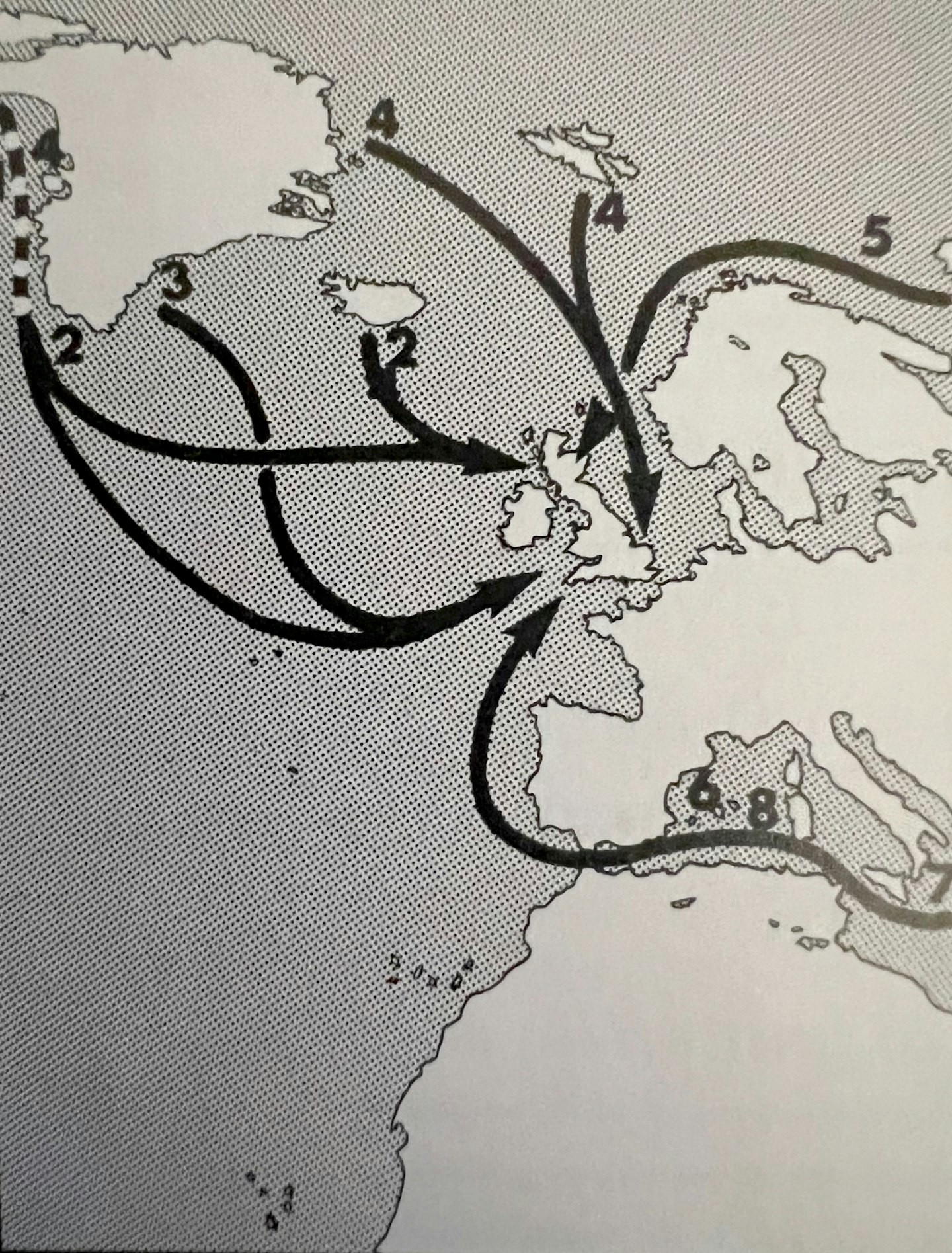

Potential arrival vectors of large gulls 1 Thayers, 2 Glaucous, 3 Iceland, 4 Ivory. 5 Siberian and Scandinavian Herring, 6 Audouin's and Mediterranean Herring, 7 Great Black-headed.

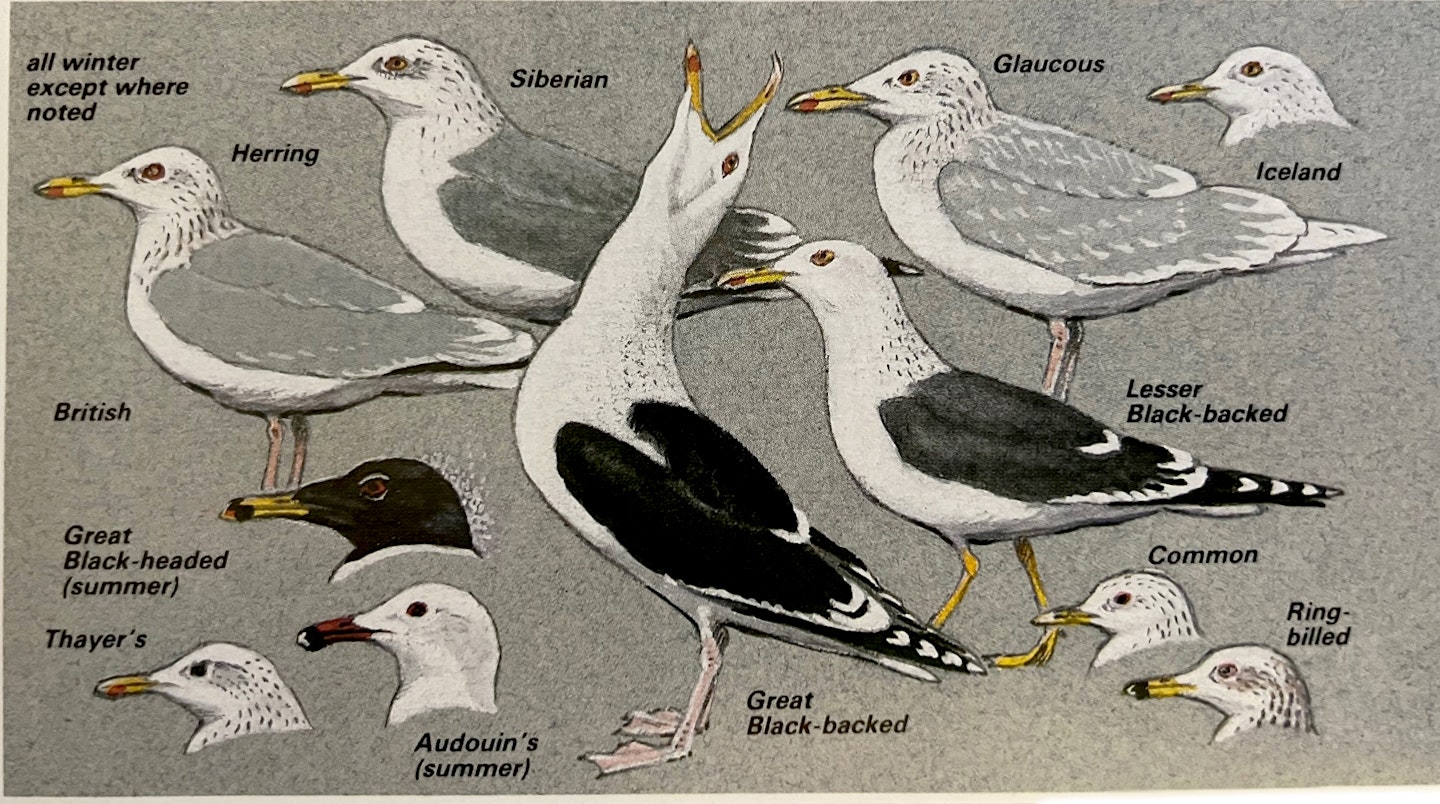

Size, structure and expression

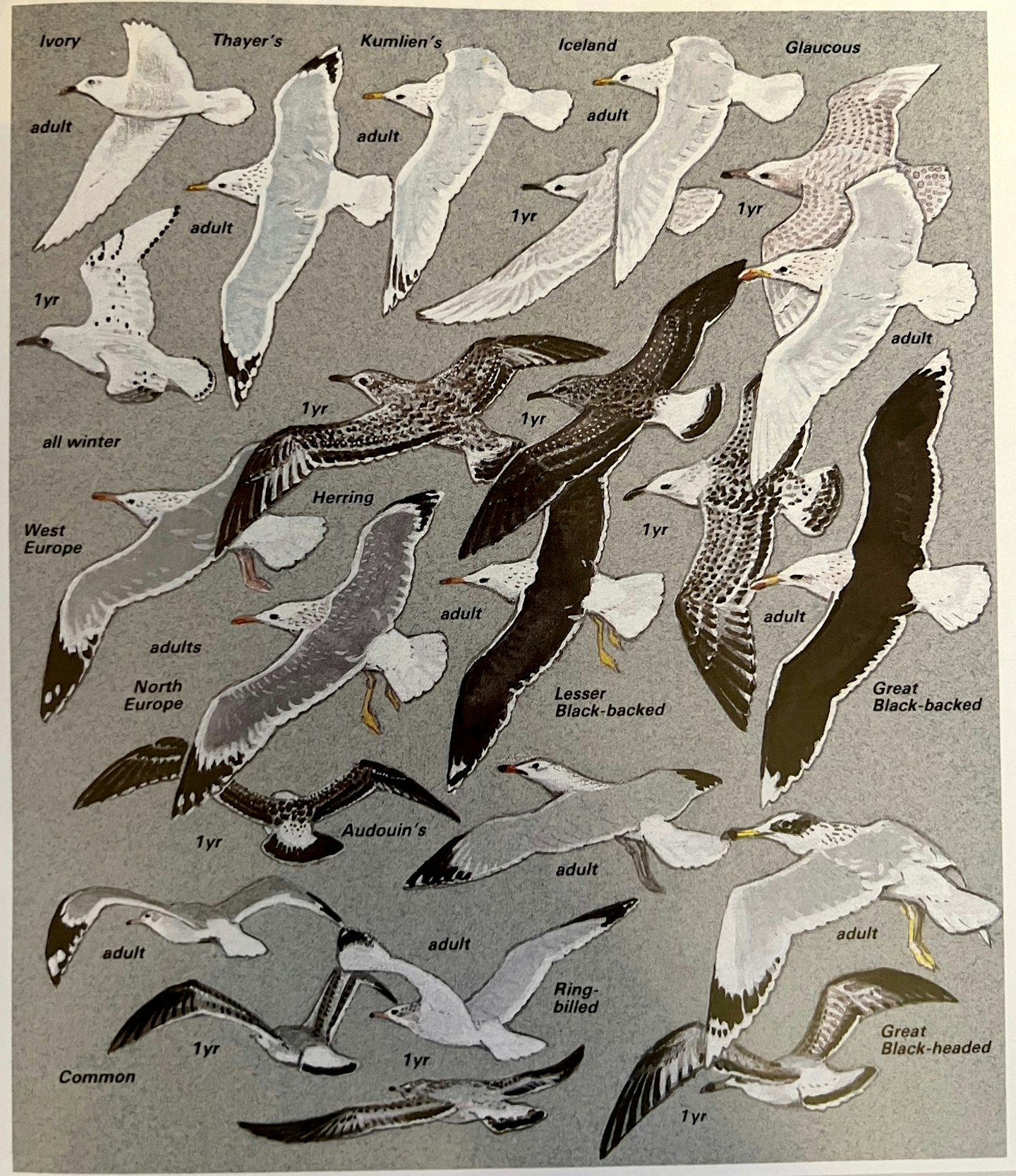

Through the 11 species on the ‘working list’ size ranges downwards in three loose groups:

(1) huge to very large containing Great Black-backed, Glaucous, and Siberian Herring,

(2) large, comprising Iceland, Thayer's, southern Herrings and Audouins and

(3) quite large to medium sized, including Ring-billed, Ivory and Common.

Between the largest and the smallest of the 11, bulk differs by almost 100% and wing span by nearly 50% and these ranges show farther in specific structure and general character.

Worth particular stress are the total elegance (and drooping bill/long forecrown of Audouin’s; the rather bulky ‘Herring-ness (not dainty ‘Common-ness’) of Ring-billed; the relative slightness and long narrow wings of the Lesser Black-backed compared to Herring; the flat head and rather short ‘barrel’ and (seemingly) wings of Glaucous; the ‘pigeon-ness’ of Iceland and Ivory due to their slighter bills and round heads; and the long bill, wings and legs of the Great Black-headed.

When you face an odd immature, your perception of such aspects of general character or ‘jizz’ (appalling word!) may be all important in not wasting time on just another Herring Gull. In combination with adult eye colours, the head shapes of the larger gulls convey distinct expression. Most look fierce, but Thayer's less so, Iceland and Audouin's almost gentle, and Common positively meek!

Flight action and feeding tactics

To cope with all sorts of sea weather and journeys, gulls have to fly superbly. All the larger ones soar, sail, careen, pad or row along, stall to dip down, and (more or less) hover.

At long range, differences in flight action are difficult to detect, except in the medium-sized lighter species.

Close to, however, some specific actions do show. Those include the heron-like wingbeats of Great Black-headed; the graceful manoeuvres of Audouin's; the slower, heavier progress of Ring-billed compared to the lighter buoyant action of Common; the more elastic strokes of the Lesser Black-backed which lack the hint of clumsiness in Herring; the lightness of Iceland compared to the lumbering weight of Glaucous; the constant power of Great Black-backed and the careening and flowing wingbeats of the Ivory.

The larger gulls share much feeding behaviour and are still learning new food sources. Their scavenging tactic makes fishing ports, sewer outfalls and even inland rubbish tips all great places for gulls.

Individual feeding skills are most marked in the ‘search and lunge’ of Audouin's, the ground foraging of Common; the skilled fishing of the Lesser Black-backed, the delicate ‘spot and pick’ of the Iceland; the carrion eating of the Ivory and the aggressive predation of Great Black-blacked and Glaucous which rival the Great Skua in killing power.

Calls

Voice is usually ignored in gull identification, but in the case of some species (and adult birds) some calls are helpful. The Great Black-headed croaks like a crow; the Audouin's gives a mew in alarm, unlike the Herring which yelps; the Ring-billed sounds more like the Herring than the Common, which mews, squeals and barks. The Iceland's voice has a shrill quality and the Glaucous almost whines at times, if it says anything at all. The Lesser Black-backed sounds gruff and the Great Black-backed gruffer still, being the basso profundo of its tribe. The long breeding calls of the large gulls are trumpeted from extreme postures, as shown in the lower plate.

Pecking order and behaviour

The species hierarchy of gulls has not been fully examined you could try to add knowledge there. But a rough peck-order is visible at common (and oft disputed) food sources. The lord is the Great Black-backed, sometimes rivalled by Glaucous, but usually seeing off both Herring and Lesser Black-backed. Herring dominates Ring-billed and Common. Other behaviours help to identification are the vulture-like carrion searches of the Great Black-backed (purposefully patrolling huge inland areas); the sudden arrival of massed migrant parties – and pasture feeding of Lesser Black-backed and Common; the association of Glaucous with fishing ports and the preference for close shore and surf associations shown by Audouin's and Ring Billed.

Plumage patterns

As adults, the bigger gulls show three types of plumage patterns:

a pair of ‘black backs’;a trio of white wings; andt he rest: ‘grey backs with variable black or dusky and white wing tips in the first and third

Unfortunately, subspecific variation obscures the easy division of the darker north-eastern and southern Herrings from the British Lesser Black-backed. Even worse, specific or subspecific or hybrid variation (yes, gull identification gets worse before it gets better!) presents serious problems particularly along the ‘row’ of Herring, Thayer's, Kumlien’s race of Iceland and typical Iceland.

The only certain clue to Thayer's is its grey-brown eye ring, unlike the yellow/red combination in the other three.

As immatures, the bigger gulls go through very complex progressions of plumage, which changes after each full autumn and partial spring moult. Only the ‘white wings’ remain an easily recognisable group. The other nine pass through (in total) scores of changes. To learn them, you must read Peter Grant's exhaustive references or the BWP texts which will guide you along the track of ‘juvenile, first-winter, first-summer, second-winter, second-summer, third-winter, third-summer, fourth-winter (for some), adult’.

This sequence is common to the huge to large species. In the medium-sized ones, the track ends at third-winter, adult. In the minefield of immature gull characters, a few are easier to see than other. The most trustworthy are the juvenile Lesser Black-backed's swarthiness (with wholly dark flight feathers and nearest coverts); the juvenile Great black-backed’s strongly chequered saddle and wing converts; the first winter Glaucous’ ‘Weetabix’ colour and large dark-ended bill; the first winter Iceland's ‘oatmeal’ colour and wholly dusky bill; the first winter Great Black-headed's dark ear patch, white rump and thick tail band; the young Audouin's rather uniform face patch and almost wholly dark face; the young Ivory's black spots and the first winter Ring-billed's paler saddle and more contrasting wing pattern, compared to Common which shows a sharp tail band

2020s update

Even the ubiquitous Collins Bird Guide, which many if not most birders possess, provides an excellent base to help with ID of large white-headed gulls, providing illustrations and descriptions of plumages not even known properly when DIMW wrote this article.

A few more large gulls have now been added to The British List. These include Audouin’s, Slaty-backed Gull and Glaucous-winged Gull, as well as the relatively recent ‘splits’ of Yellow-legged Gull, Caspian Gull and American Herring Gull (which were all included in Herring Gull in the 1980s). Thayer’s is rare but regular, but not yet considered a full species for The British List purposes

Incidentally, contrary to what DIMW states, there has only been one accepted record of Great Black-headed Gull aka Pallas’s Gull, which was back in 1859 (in Devon)!

To hear the various calls of the many gulls, check out the amazing resource provided by xeno-canto.org