Under threat in Summer

December 1986

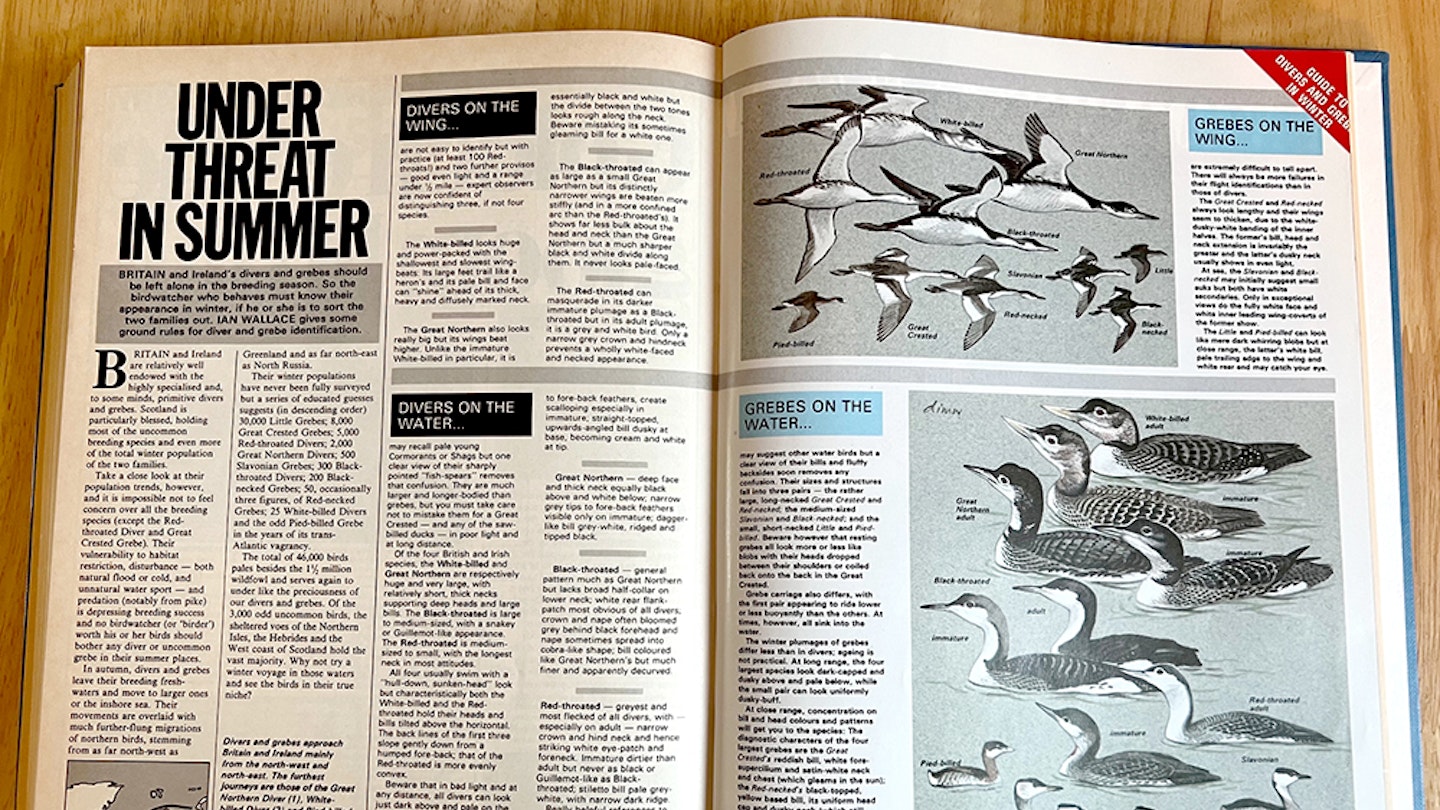

BRITAIN and Ireland's divers and grebes should be left alone in the breeding season. So, the birdwatcher who behaves must know their appearance in winter, if he or she is to sort the two families out. IAN WALLACE gives some ground rules for diver and grebe identification

BRITAIN and Ireland are relatively well endowed with the highly specialised and, to some minds, primitive divers and grebes. Scotland is particularly blessed, holding most of the uncommon breeding species and even more of the total winter population of the two families.

Take a close look at their population trends, however, and it is impossible not to feel concern over all the breeding species (except the Red-throated Diver and Great Crested Grebe). Their vulnerability to habitat restriction, disturbance – both natural flood or cold, and unnatural water sport – and predation (notably from pike) is depressing breeding success and no birdwatcher (or "birder') worth his or her birds should bother any diver or uncommon grebe in their summer places.

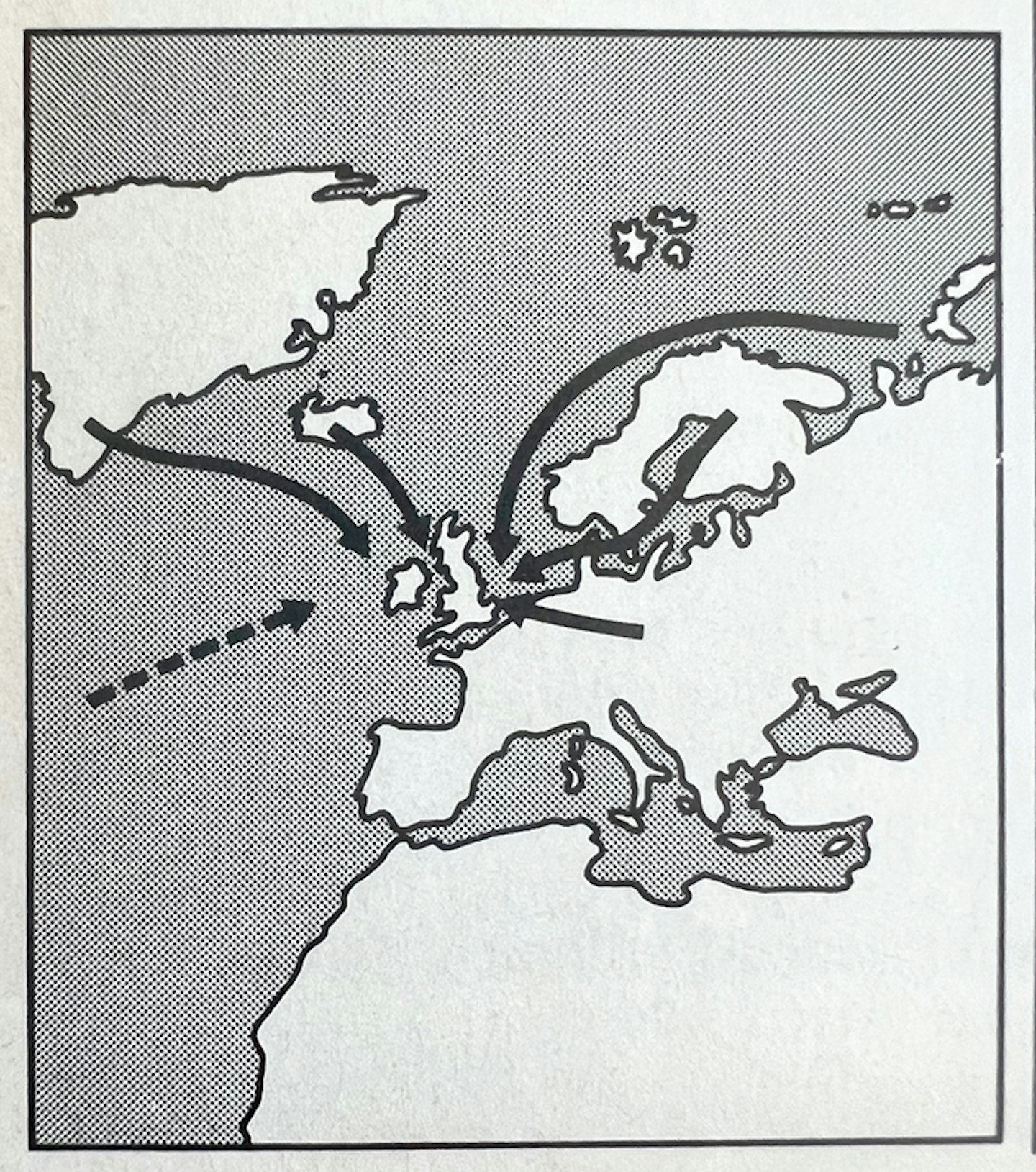

In autumn, divers and grebes leave their breeding fresh waters and move to larger ones or the inshore sea. Their movements are overlaid with much further-flung migrations of northern birds, stemming from as far north-west as Greenland and as far north-east as North Russia.

Their winter populations have never been fully surveyed but a series of educated guesses suggests (in descending order) 30,000 Little Grebes; 8,000 Great Crested Grebes; 5,000 Red-throated Divers; 2,000 Great Northern Divers: 500 Slavonian Grebes; 300 Black-throated Divers; 200 Black-necked Grebes; 50, occasionally three figures, of Red-necked Grebes; 25 White-billed Divers and the odd Pied-billed Grebe in the years of its trans-Atlantic vagrancy.

The total of 46,000 birds pales besides the wildfowl numbers we get in winter and serves again to underline the preciousness of our divers and grebes. Of the 3.000 odd uncommon birds, the sheltered voes of the Northern Isles, the Hebrides and the West coast of Scotland hold the vast majority. Why not try a winter voyage in those waters and see the birds in their true niche?

Divers and grebes approach Britain and Ireland mainly from the north-west and north-east. The furthest journeys are those of the Great Northern Diver (1), White-billed Diver (2) and the Pied-billed Grebe (3) The shorter-ranged ones stem fromFenno-Scandia (4) and - in heard weather - the Low Countries (5). immigrations begin in September and normal winter presences peak in January and February, with withdrawals in early spring. A few immatures or young adults may linger in summer.

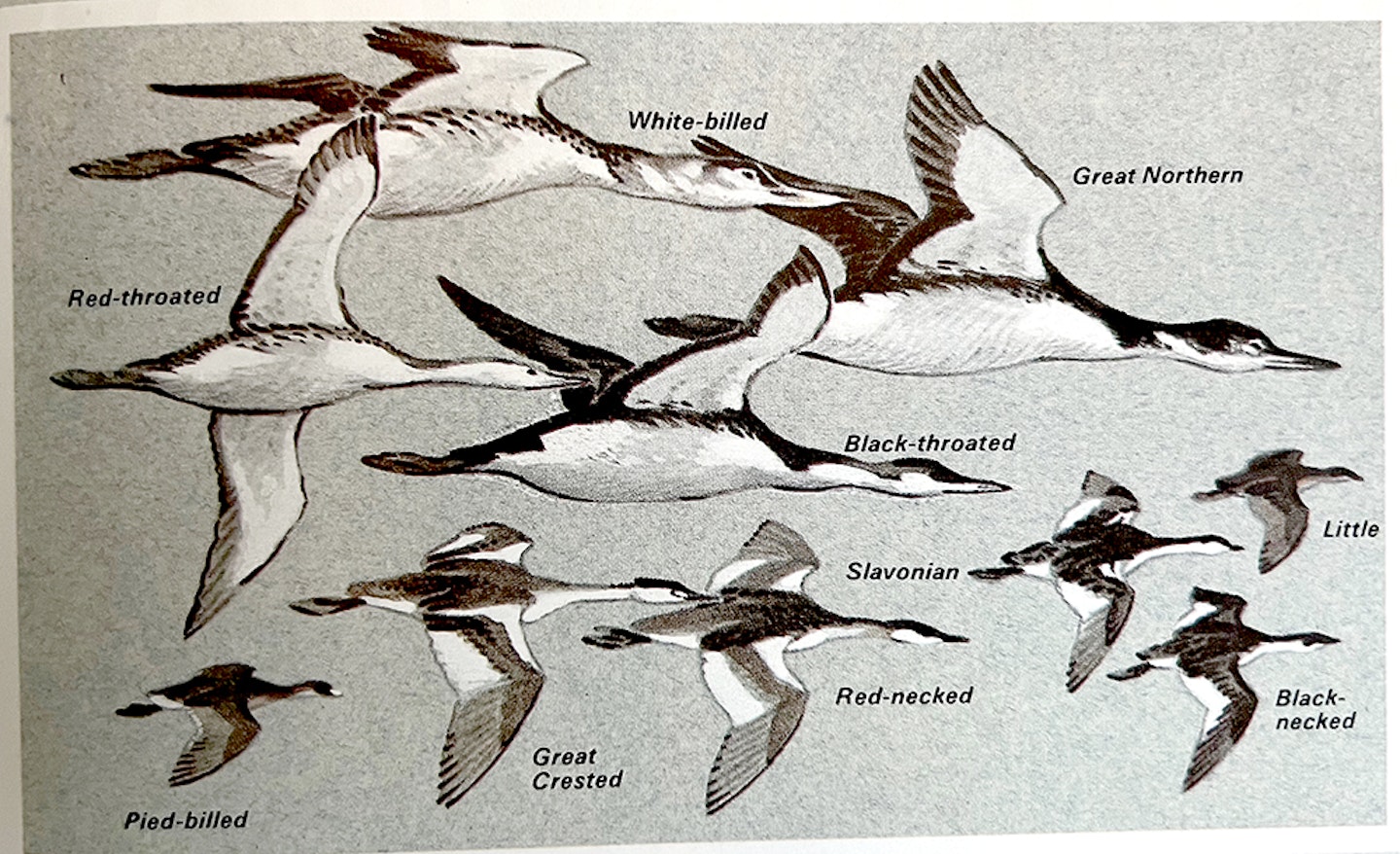

DIVERS ON THE WING…

…are not easy to identify, but with practice (at least 100 Red-throateds) and two further provisos – good, even light and a range under half a mile – expert observers can be confident of distinguishing three, if not four species.

The White-billed looks huge and power-packed, with the shallowest and slowest wing-beats. Its large feet trail like a heron’s, and its pale bill and face can ‘shine’ ahead of its thick, heavy and diffusely marked neck.

The Great Northern also looks really big, but its wings beat higher. Unlike the immature White-billed in particular, it is essentially black and white but the divide between the two tones looks rough along the neck. Beware mistaking its sometimes gleaming bill for a white one.

The Black-throated can appear as large as a small Great Northern but its distinctly narrower wings are beaten more stiffly (and in a more confined arc than the Red-throated's). It shows far less bulk about the head and neck than the Great Northern but a much sharper black and white divide along them. It never looks pale-faced.

The Red-throated can masquerade in its darker immature plumage as a Black-throated but in its adult plumage, it is a grey and white bird. Only a narrow grey crown and hindneck prevents a wholly white- faced and -necked appearance.

GREBES ON THE WING...

…are extremely difficult to tell apart. There will always be more failures in their flight identifications than in those of divers. The Great Crested and Red-necked always look lengthy and their wings seem to thicken, due to the white-dusky-white banding of the inner halves. The former's bill, head and neck extension is invariably the greater and the latter's dusky neck usually shows in even light.

At sea, the Slavonian and Black-necked may initially suggest small auks but both have white secondaries. Only in exceptional views do the fully white face and white inner leading wing-coverts of the former show.

The Little and Pied-billed can look like mere dark whirring blobs but at close range, the latter's white bill, pale trailing edge to the wing and white rear end may catch your eye.

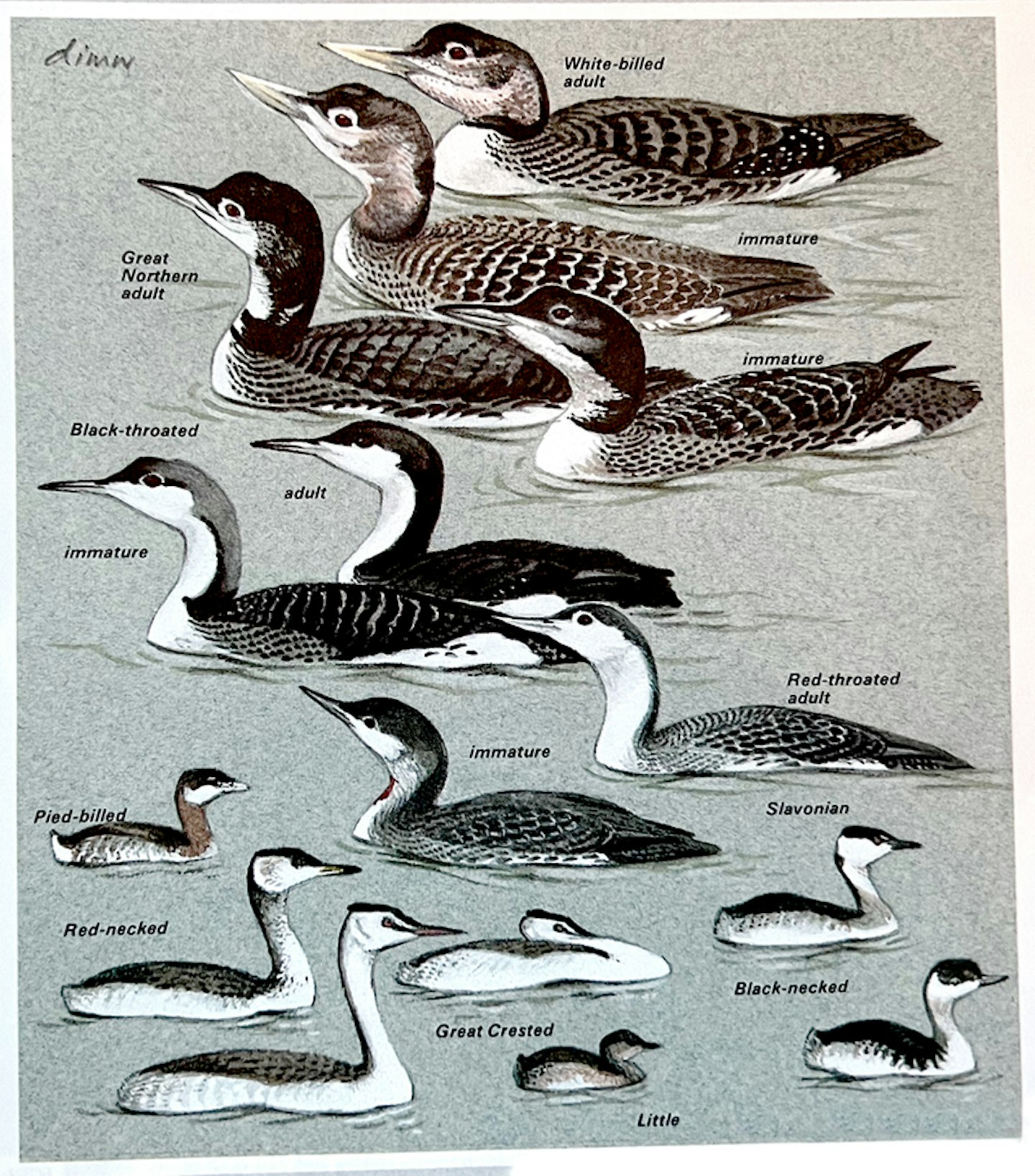

DIVERS ON THE WATER…

…may recall pale young Cormorants or Shags but one clear view of their sharply pointed "fish-spears" removes that confusion. They are much larger and longer-bodied than grebes, but you must take care not to mistake them for a Great Crested – and any of the saw-billed ducks – in poor light and at long distance.

Of the four British and Irish species, the White-billed and Great Northern are respectively huge and very large, with relatively short, thick necks supporting deep heads and large bills. The Black-throated is large to medium-sized, with a snakey or Guillemot-like appearance.

The Red-throated is medium-sized to small, with the longest neck in most attitudes.

All four usually swim with a "hull-down, sunken-head" look, but characteristically both the White-billed and the Red-throated hold their heads and bills tilted above the horizontal. The back lines of the first three slope gently down from a humped fore-back; that of the Red-throated is more evenly convex.

Beware that in bad light and at any distance, all divers can look just dark above and pale on the foreneck, chest and along the waterline. In good light and at close range, the following distinctive plumage and bill characters appear:

White-billed – deep face and thick neck buff-white, with only narrow dusky crown and windneck pattern; broad dun tips to fore-back feathers create scalloping, especially in immature; straight-topped, upwards-angled bill dusky at base, becoming cream and white at tip.

Great Northern – deep face and thick neck equally black above and white below; narrow grey tips to fore-back feathers visible only on immature; dagger-like bill grey-white, ridged and tipped black.

Black-throated – general pattern much as Great Northern but lacks broad half-collar on lower neck; white rear flank-patch most obvious of all divers; crown and nape often bloomed grey behind black forehead and nape sometimes spread into cobra-like shape; bill coloured like Great Northern's but much finer and apparently decurved.

Red-throated – greyest and most flecked of all divers, with – especially on adult – narrow crown and hind neck and hence striking white eye-patch and foreneck. Immature dirtier than adult but never as black or Guillemot-like as Black-throated; stiletto bill pale grey-white, with narrow dark ridge.

Really helpful references to diver and grebe identification are few. The most up-to-date and comprehensive are those in The Birds of the Western Palearctic, Vol. 1 (but the plates are disappointing) and – on divers alone – in the August 1986 issue of British Birds (but see if you agree with me that one of the Black-throated photographs is actually of a Great Northern.

GREBES ON THE WATER...

…may suggest other water birds, but a clear view of their bills and fluffy backsides soon removes any confusion. Their sizes and structures fall into three pairs – the rather large, long-necked Great Crested and Red-necked; the medium-sized Slavonian and Black-necked; and the small, short-necked Little and Pied-billed. Beware however that resting grebes all look more or less like blobs with their heads dropped between their shoulders or coiled back onto the back in the Great Crested.

Grebe carriage also differs, with the first pair appearing to ride lower or less buoyantly than the others. At times, however, all sink into the water.

The winter plumages of grebes differ less than in divers; ageing is not practical. At long range, the four largest species look dark-capped and dusky above and pale below, while the small pair can look uniformly dusky-buff.

At close range, concentration on bill and head colours and patterns will get you to the species: The diagnostic characters of the four largest grebes are the Great Crested's reddish bill, white fore-supercilium and satin-white neck and chest (which gleams in the sun); the Red-necked's black-topped, yellow based bill, its uniform head cap and dusky neck (which still contrasts with its white face); the Slavonian's dusky-based but pale-topped bill, slight fore-supercilium and restricted crown, and the Black-necked's wholly dusky and tip-tilted bill (which is also finer than the Slavonian's little dagger) and its dusky rear ear-coverts. From the ultimate blob of the

2022 UPDATE

While every bit of Ian’s advice holds good, population figures have changed a little, to:

Great Northern Diver – 2,500 wintering birds

Black-throated Diver – 200 breeding pairs, 560 wintering birds

Red-throated Diver – 1,300 breeding pairs, 17,000 wintering birds

White-billed Divers – maybe 50-60 wintering birds, with an early spring concentration in the Moray Firth

Great Crested Grebe – 4.600 breeding pairs, 19,000 wintering birds

Red-necked Grebe – occasional breeding pairs, 50 wintering birds

Black-necked Grebe – 50-60 breeding pairs, 130 wintering birds

Slavonian Grebe – 30 breeding pairs, 1,100 wintering birds

Little Grebe – 5,300 breeding pairs, 16,000 wintering birds